Coaches For All: Late Georgian Travel Alan Payne June 2019

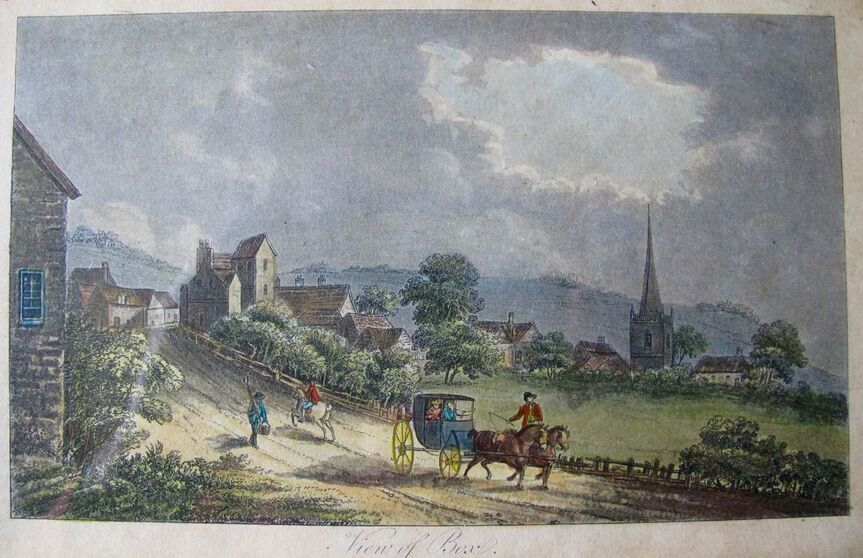

On 2 October 1784 the Bristol Journal made an announcement which totally altered the story of Box: The proprietors of the (Mail Diligence) carriage, having agreed to convey the mail to and from London and Bristol in sixteen hours ... will set off every night at eight o'clock from the Swan-with-two-Necks, Lad Lane, London, and arrive at the Three Tuns Inn, Bath, before ten the next morning.[1] It was the first mail coach and the centre of Box was never the same afterwards. We might imagine that every morning a crowd would gather to hear the distant sound of a horn which announced the mail carriage's departure from Corsham and started a wave of activity in the village. The road was cleared of obstructions and the turnpike tollgate opened as the village prepared for the mail coach.[2]

The innkeepers of the Queen's Head and The Bear Hotel fussed around to receive the mail and to invite distinguished visitors into their inn. Postboys prepared to change horses on the coach and to hire post-chaises for travellers disembarking at Box. A crowd of people gathered: onlookers wanting to catch site of travellers in the latest London fashions; beggars asking for a donation; hawkers offering trinkets, opportunists providing assistance in adverse weather, lavender or smelling salts. Sometimes the carriage raced through the village, sometimes it stopped to change horses or water them. From now on the centre of Box was where it was happening in the parish.

Box in 1792

That might be an idealised version of late Georgian coach travel but we can go further with a contemporary description of Box in 1792. Archibald Robertson's description of the eastern approach to the village was one which would have been recognised by Victorian and modern travellers:

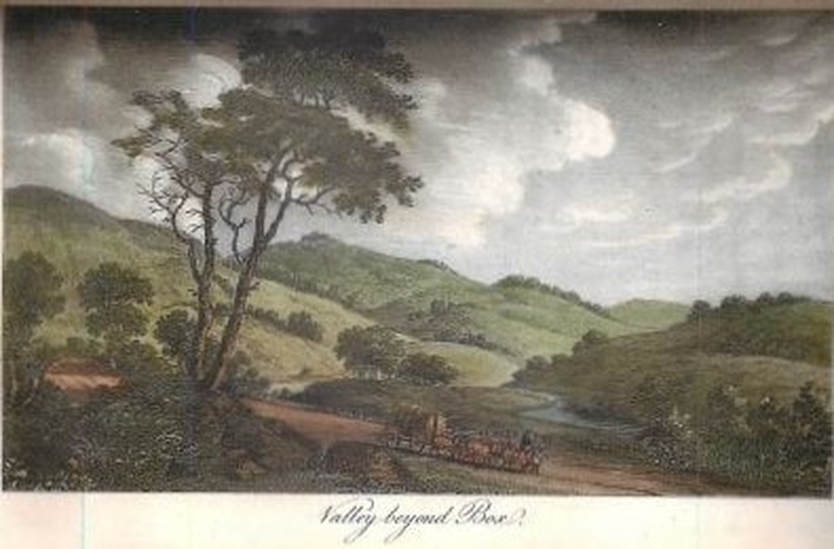

On descending the declivity of a steep hill (from Hartham, Pickwick) , as we approach Box, we command prospects down a rich and well-cultivated valley, through which a rivulet flows; the high ground on the left becomes more lofty, and in its face appear many quarries of beautiful white free-stone, of the same quality with that generally known by the name of Bath-stone.[3]

But the centre of the village was very different in 1792, compact, undeveloped and taking a slightly different route:

This is a neat village, situated at the foot of a hill, part of that ridge of high grounds which form the south side of the vale we have mentioned. It stands about one hundred and one miles from London and six miles from Bath.[4]

The implication is that Robertson thought the village centre was not much more than the properties from the Market Place to the Bear Inn and the houses in Ashley. Of course, he did not view the outlying hamlets. He goes on to describe the western exit of the village going up Ashley Lane then down towards the Bath Road at Shockerwick:

Beyond this village, a steep descent brings us lower into the valley; and upon an eminence on the right, about a mile from it, stands a handsome house, with wings, the residence of Mr Wiltshire (Shockerwick House).

The innkeepers of the Queen's Head and The Bear Hotel fussed around to receive the mail and to invite distinguished visitors into their inn. Postboys prepared to change horses on the coach and to hire post-chaises for travellers disembarking at Box. A crowd of people gathered: onlookers wanting to catch site of travellers in the latest London fashions; beggars asking for a donation; hawkers offering trinkets, opportunists providing assistance in adverse weather, lavender or smelling salts. Sometimes the carriage raced through the village, sometimes it stopped to change horses or water them. From now on the centre of Box was where it was happening in the parish.

Box in 1792

That might be an idealised version of late Georgian coach travel but we can go further with a contemporary description of Box in 1792. Archibald Robertson's description of the eastern approach to the village was one which would have been recognised by Victorian and modern travellers:

On descending the declivity of a steep hill (from Hartham, Pickwick) , as we approach Box, we command prospects down a rich and well-cultivated valley, through which a rivulet flows; the high ground on the left becomes more lofty, and in its face appear many quarries of beautiful white free-stone, of the same quality with that generally known by the name of Bath-stone.[3]

But the centre of the village was very different in 1792, compact, undeveloped and taking a slightly different route:

This is a neat village, situated at the foot of a hill, part of that ridge of high grounds which form the south side of the vale we have mentioned. It stands about one hundred and one miles from London and six miles from Bath.[4]

The implication is that Robertson thought the village centre was not much more than the properties from the Market Place to the Bear Inn and the houses in Ashley. Of course, he did not view the outlying hamlets. He goes on to describe the western exit of the village going up Ashley Lane then down towards the Bath Road at Shockerwick:

Beyond this village, a steep descent brings us lower into the valley; and upon an eminence on the right, about a mile from it, stands a handsome house, with wings, the residence of Mr Wiltshire (Shockerwick House).

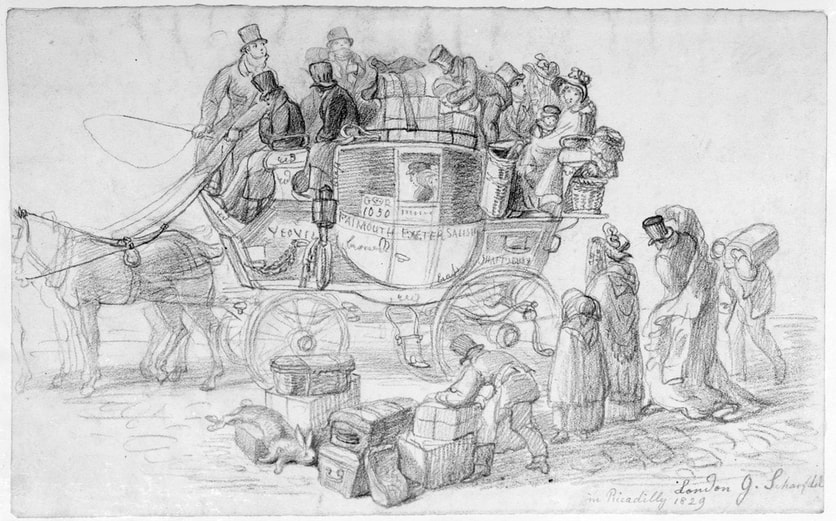

By the 1820s, twenty coaches a day were travelling from London to Bath, as well as rented post-chaises (called yellow bounders because of their colour), mail coaches, horses and carriages, local horse riders and pedestrian traffic. By 1835 there was so much road traffic that a Highways Act enforced driving on the left. The road was highly profitable, in 1818 generating a profit of £676.7s clear of the salaries for collecting the same and in 1836 averaging an income of £744 with expenses of only £515.[5] The journey was still fraught with difficulties, however. In December 1836, three outside passengers were found to have died of cold on arrival at Chippenham.[6]

There were constant improvements made to the route and the surface of the road, part of initiatives to reduce travel times. In 1839 contracts were tendered for cutting, forming, steining, making, fencing and completing a section of 45 chains from the Box turnpike up the hill to the Rising Sun inn.[7] The solution to improving the surfacing of roads was disputed by engineers

Thomas Telford and John Loudon McAdam. Telford advocated a cambered road with a base of large stones, then a 6 inch layer of broken stones, topped off by a gravel surface. He proposed reducing gradients, straightening the route and better drainage. McAdam proposed a smooth elastic road surface placed directly on the natural sub-soil (a stone-based surface before the development of tar surfaces in 1910).[8] He was appointed surveyor-general to the Bristol Trust in 1816, where he introduced professional surveyors and better administration.[9]

There were constant improvements made to the route and the surface of the road, part of initiatives to reduce travel times. In 1839 contracts were tendered for cutting, forming, steining, making, fencing and completing a section of 45 chains from the Box turnpike up the hill to the Rising Sun inn.[7] The solution to improving the surfacing of roads was disputed by engineers

Thomas Telford and John Loudon McAdam. Telford advocated a cambered road with a base of large stones, then a 6 inch layer of broken stones, topped off by a gravel surface. He proposed reducing gradients, straightening the route and better drainage. McAdam proposed a smooth elastic road surface placed directly on the natural sub-soil (a stone-based surface before the development of tar surfaces in 1910).[8] He was appointed surveyor-general to the Bristol Trust in 1816, where he introduced professional surveyors and better administration.[9]

Passenger and Mail Coaches

Despite the Bath Chronicle's assertion, it was by no means certain that the 1761 road would be successful until John Palmer,

a Bath theatre owner, conceived the idea of sending mail by high speed coach in 1784.[10] Trials were held on the London to Bristol run and the system was introduced nationally.[11] The old route from London to Bath through Melksham continued with daily coaches but it was subject to severe delays - in 1786 the mail coach was delayed by ten hours due to snow drifts.[12] The more direct route through Box became the standard route, carrying the mail and four or six passengers. Each coach had a guard armed with a blunderbuss and a regulation watch to monitor the coaches strict timetable for which speed was the essence. So they used the London Road route through the parish and the development of the centre of Box took off.

In 1830, a decade before the railways came to the village, there were thirteen coaches plying daily between London and Bath, including two Royal Mails. Six couriers went through Chippenham, Corsham and Box, one providing both day and night services. The remainder of services on the London to Bath route went via Devizes and Melksham through Kingsdown. Of those taking the route via Box one terminated at Bath and the rest went through to Bristol. The price for travelling was 4d a mile inside and 2d outside, with slightly different rates for night coaches.[13] To those rates there had to be paid 5s for tips to the coachmen and guard (2s.6d each) and half-a-sovereign (10s) for refreshments en route. Accidents had been reduced by road improvements and in 1833 no highwaymen were reported as working on the Bath roads, although there was petty theft.

We have a marvellous description of the coaches that used the route in 1830 with names such as The Monarch, The Regulator and The Self-Defence. Speed sometimes came into conflict with safety and in 1833 The Monarch overturned at Reading killing a passenger Henry Harding Head of Bath, aged 28.[14] Opportunist robbery continued to be an issue and in 1840 Samuel Powell was charged with stealing 14 crumpets, a shirt and other articles value 12s.[15] He was sentenced to 5 month's imprisonment with hard labour.

Despite the Bath Chronicle's assertion, it was by no means certain that the 1761 road would be successful until John Palmer,

a Bath theatre owner, conceived the idea of sending mail by high speed coach in 1784.[10] Trials were held on the London to Bristol run and the system was introduced nationally.[11] The old route from London to Bath through Melksham continued with daily coaches but it was subject to severe delays - in 1786 the mail coach was delayed by ten hours due to snow drifts.[12] The more direct route through Box became the standard route, carrying the mail and four or six passengers. Each coach had a guard armed with a blunderbuss and a regulation watch to monitor the coaches strict timetable for which speed was the essence. So they used the London Road route through the parish and the development of the centre of Box took off.

In 1830, a decade before the railways came to the village, there were thirteen coaches plying daily between London and Bath, including two Royal Mails. Six couriers went through Chippenham, Corsham and Box, one providing both day and night services. The remainder of services on the London to Bath route went via Devizes and Melksham through Kingsdown. Of those taking the route via Box one terminated at Bath and the rest went through to Bristol. The price for travelling was 4d a mile inside and 2d outside, with slightly different rates for night coaches.[13] To those rates there had to be paid 5s for tips to the coachmen and guard (2s.6d each) and half-a-sovereign (10s) for refreshments en route. Accidents had been reduced by road improvements and in 1833 no highwaymen were reported as working on the Bath roads, although there was petty theft.

We have a marvellous description of the coaches that used the route in 1830 with names such as The Monarch, The Regulator and The Self-Defence. Speed sometimes came into conflict with safety and in 1833 The Monarch overturned at Reading killing a passenger Henry Harding Head of Bath, aged 28.[14] Opportunist robbery continued to be an issue and in 1840 Samuel Powell was charged with stealing 14 crumpets, a shirt and other articles value 12s.[15] He was sentenced to 5 month's imprisonment with hard labour.

| coaches_in_1830.doc | |

| File Size: | 40 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

Transportation of Goods

Much of the coach activity was for the carriage of letters, parcels and certain goods from the new manufactories of industrial Britain, the Empire and the world. Items that we consider to be everyday commodities, like tea, coffee and sugar, were imported from all over the world and were so expensive they were prohibited for poorhouse residents: any person ... found drinking foreign tea ... shall not receive any future relief.[16] In addition to high value items, most farm crops had to be conveyed on local roads to market, mills and manufactories. These were conveyed by four-wheeled wagon with 2 axles needing 2 or more horses, which replaced the old carts and packhorse trains.[17]

What is perhaps more remarkable is the variety of goods in circulation in the early Georgian period, as indicated by the assets left by the owner of the Bear Inn in 1726.[18] They included pewter dishes, plates, chamber pots, cheese plates, drinking vessels and candle sticks. There were brass pots, saucepans, kettles, and candle sticks and copper pots and teapots. In the kitchen were iron goods comprising spits, roasting, dripping pans, pokers and pot hooks and around the fireplaces including grate, sliders, firedogs, fender, shovels and bellows all derived from English manufacturing areas. Then there were sitting and bedding furnishings like chairs, tables, stools, curtains, rugs, feather beds, blankets, bolsters, quilts, blankets, chest of drawers. All of these items would have been conveyed into Box by horse-drawn carriages and wagons.

Road carriage was a reliable method of transport, unlike rivers which were unnavigable in dry seasons. Their use was recognised from the outset of the Georgian period and, as early as 1692, Justices of the Peace were instructed to set carriage rates for their areas.[19] For Box the rate was set as 13d a ton-mile but higher rates for small goods.

Much of the coach activity was for the carriage of letters, parcels and certain goods from the new manufactories of industrial Britain, the Empire and the world. Items that we consider to be everyday commodities, like tea, coffee and sugar, were imported from all over the world and were so expensive they were prohibited for poorhouse residents: any person ... found drinking foreign tea ... shall not receive any future relief.[16] In addition to high value items, most farm crops had to be conveyed on local roads to market, mills and manufactories. These were conveyed by four-wheeled wagon with 2 axles needing 2 or more horses, which replaced the old carts and packhorse trains.[17]

What is perhaps more remarkable is the variety of goods in circulation in the early Georgian period, as indicated by the assets left by the owner of the Bear Inn in 1726.[18] They included pewter dishes, plates, chamber pots, cheese plates, drinking vessels and candle sticks. There were brass pots, saucepans, kettles, and candle sticks and copper pots and teapots. In the kitchen were iron goods comprising spits, roasting, dripping pans, pokers and pot hooks and around the fireplaces including grate, sliders, firedogs, fender, shovels and bellows all derived from English manufacturing areas. Then there were sitting and bedding furnishings like chairs, tables, stools, curtains, rugs, feather beds, blankets, bolsters, quilts, blankets, chest of drawers. All of these items would have been conveyed into Box by horse-drawn carriages and wagons.

Road carriage was a reliable method of transport, unlike rivers which were unnavigable in dry seasons. Their use was recognised from the outset of the Georgian period and, as early as 1692, Justices of the Peace were instructed to set carriage rates for their areas.[19] For Box the rate was set as 13d a ton-mile but higher rates for small goods.

Canals for Box

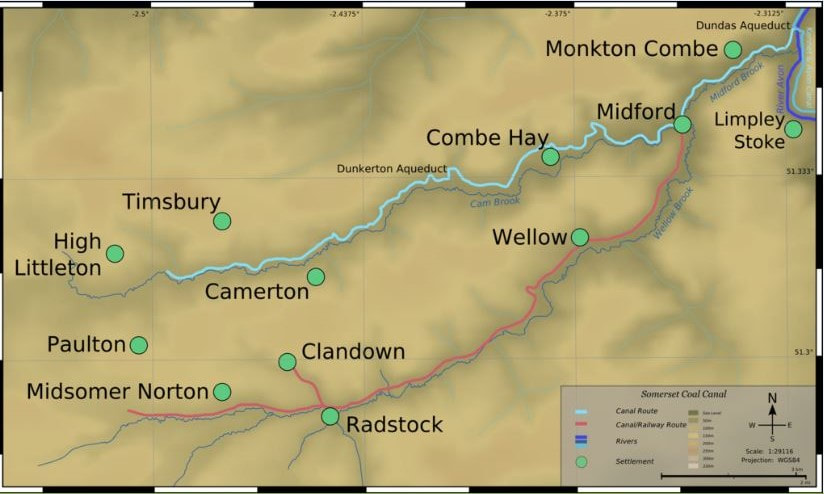

The closest canal to Box was the Kennet & Avon, accessed by short-haul carriage from Bath or Bradford-on-Avon. The River Kennet was navigable to London after 1723 with 21 locks and the Avon Navigation Canal provided access between Shropshire and Bath after 1731.[20] Both provided coal to Box. By 1804 Box was a regular destination for river hauliers from London, such as White and Barnard, who advertised the village as a recipient of London goods.[21] The Kennet & Avon Canal was planned after 1794 and then it took sixteen years until 1810 to complete.[22] It was plagued by inflation in the Napoleonic period, weirs on the Avon between Bath and Keynsham and technical difficulties.[23] It opened in November 1810 but was little used for stone traffic, most of its trade being coal from the opening of the Somerset Coal Canal.[24] But was too late and not sufficiently reliable to be significant in the village's Georgian period.[25] However, it did carry huge quantities of traffic in the years just before the railway opened, in 1838-39 about 341,878 tons of goods.[26]

The same was true of other local canals. The Somerset Coal Canal into Bath opened after 1799 but was plagued with water seepage at Combe Hay and was not reliable for commercial use, although it probably was the first time that coal was cheap enough for domestic heating and cooking. The Wilts and Berks Canal, which joined the Kennet & Avon to Chippenham and on to London, opened in 1810 and the North Wilts Canal the same year.[27] The main use of these canals was the onward dispatch of Somerset coal - they were too far from Box to be of consequence. So horse-drawn wagons on the road routes remained supreme at the end of the Georgian period.

The closest canal to Box was the Kennet & Avon, accessed by short-haul carriage from Bath or Bradford-on-Avon. The River Kennet was navigable to London after 1723 with 21 locks and the Avon Navigation Canal provided access between Shropshire and Bath after 1731.[20] Both provided coal to Box. By 1804 Box was a regular destination for river hauliers from London, such as White and Barnard, who advertised the village as a recipient of London goods.[21] The Kennet & Avon Canal was planned after 1794 and then it took sixteen years until 1810 to complete.[22] It was plagued by inflation in the Napoleonic period, weirs on the Avon between Bath and Keynsham and technical difficulties.[23] It opened in November 1810 but was little used for stone traffic, most of its trade being coal from the opening of the Somerset Coal Canal.[24] But was too late and not sufficiently reliable to be significant in the village's Georgian period.[25] However, it did carry huge quantities of traffic in the years just before the railway opened, in 1838-39 about 341,878 tons of goods.[26]

The same was true of other local canals. The Somerset Coal Canal into Bath opened after 1799 but was plagued with water seepage at Combe Hay and was not reliable for commercial use, although it probably was the first time that coal was cheap enough for domestic heating and cooking. The Wilts and Berks Canal, which joined the Kennet & Avon to Chippenham and on to London, opened in 1810 and the North Wilts Canal the same year.[27] The main use of these canals was the onward dispatch of Somerset coal - they were too far from Box to be of consequence. So horse-drawn wagons on the road routes remained supreme at the end of the Georgian period.

Aftermath

From the outset, the turnpikes realised the threat that the railways posed to their business. In 1835 a group of them petitioned the House of Commons that if such railways shall prove materially superior to turnpike roads, the present trade of your petitioners will be much lessened, if not wholly destroyed.[28] The issue was the structural basis of the railways, formed as joint-stock, public undertakings, dependent on the vagaries of local landowners and parish officials. Nonetheless, new turnpikes were still being built in Box as late as 1832, when consideration was given to the building of a toll gate at a certain place called Chapel Plaister.[29] But the turnpike trusts became increasingly unpopular and raised insufficient funds to maintain the routes whilst their very presence caused considerable local annoyance and avoidance was commonplace. The end of the turnpikes came locally in 1835 when the Chippenham Turnpike Trust was wound up and the Blue Vein and Bricker’s Barn Trusts were amalgamated into a Corsham Trust.[30] By 1870 this Corsham turnpike was wound up, the tollhouse in the centre of Box pulled down and the one at Blue Vein was sold off for £50.[31] The mail coach ceased soon after the railways opened and it was alleged that in 1844 there was not a single mail coach running out of London.[32] Often there was much rejoicing at the demise of the turnpike era. At Devizes, the people celebrated in 1868 with a band playing the National Anthem.[33] In Box the arrival of the railways in 1841 caused the total demise of the turnpike system.

Goods transported on the roads seems so common in our modern lives that it might seem eternal. This isn't true and the variety of products was seen to be a marvel of the new age in Georgian Box, running set routes and timetables, achieved by local carriers and hauliers from market town to the village. It was a major feat to bring goods to Box and at first painfully slow, even for passenger travel. To illustrate this, London carriages are reputed to have gone at walking pace (4 miles per hour) and the Mail coach at a marvellous speed of 8 miles per hour, the fastest that human beings had ever experienced. In some respects the 1761 road was as important as the arrival of the railways a century later, perhaps the precedent to the railway route.

From the outset, the turnpikes realised the threat that the railways posed to their business. In 1835 a group of them petitioned the House of Commons that if such railways shall prove materially superior to turnpike roads, the present trade of your petitioners will be much lessened, if not wholly destroyed.[28] The issue was the structural basis of the railways, formed as joint-stock, public undertakings, dependent on the vagaries of local landowners and parish officials. Nonetheless, new turnpikes were still being built in Box as late as 1832, when consideration was given to the building of a toll gate at a certain place called Chapel Plaister.[29] But the turnpike trusts became increasingly unpopular and raised insufficient funds to maintain the routes whilst their very presence caused considerable local annoyance and avoidance was commonplace. The end of the turnpikes came locally in 1835 when the Chippenham Turnpike Trust was wound up and the Blue Vein and Bricker’s Barn Trusts were amalgamated into a Corsham Trust.[30] By 1870 this Corsham turnpike was wound up, the tollhouse in the centre of Box pulled down and the one at Blue Vein was sold off for £50.[31] The mail coach ceased soon after the railways opened and it was alleged that in 1844 there was not a single mail coach running out of London.[32] Often there was much rejoicing at the demise of the turnpike era. At Devizes, the people celebrated in 1868 with a band playing the National Anthem.[33] In Box the arrival of the railways in 1841 caused the total demise of the turnpike system.

Goods transported on the roads seems so common in our modern lives that it might seem eternal. This isn't true and the variety of products was seen to be a marvel of the new age in Georgian Box, running set routes and timetables, achieved by local carriers and hauliers from market town to the village. It was a major feat to bring goods to Box and at first painfully slow, even for passenger travel. To illustrate this, London carriages are reputed to have gone at walking pace (4 miles per hour) and the Mail coach at a marvellous speed of 8 miles per hour, the fastest that human beings had ever experienced. In some respects the 1761 road was as important as the arrival of the railways a century later, perhaps the precedent to the railway route.

References

[1] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, 1968, David & Charles, p.110-111

[2] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, p.153

[3] Archibald Robertson, Topographical Survey of the Great Road from London to Bath, 1792, p.70

[4] Archibald Robertson, Topographical Survey of the Great Road from London to Bath, 1792, p.70-71

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 29 January 1818 and Select Reports and Papers of House of Commons, Public works, Vol 38,

The Turnpike Roads in England and Wales, 1836, p.236

[6] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, 1988, Ashbourne, p.171

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 23 May 1839

[8] Paul Hindle, Roads and Tracks for Historians, 2001, Phillimore & Co Ltd, p.128

[9] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, 1972, Cambridge University Press, p.143-7

[10] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic, p.110

[11] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1988, Paladin, p.354

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 6 October 1785 and 2 March 1786

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 26 November 1938

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 28 March 1833

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 16 April 1840

[16] David Ibberson, The Box Collection, Volume 2, 1989, p.12

[17] Dorian Gerhold, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press p.xiv

[18] Inventory of John Bayly, 8 September 1726, courtesy Anna Grayson

[19] TS Willan, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press p.99-102

[20] Kenneth R Clew, The Kennet & Avon Canal, 1968, David & Charles, p.20

[21] The Bath Chronicle, 14 June 1804

[22] Valerie Bowyer, Along the Canal: The Kennet & Avon from Bath to Bradford-on-Avon, 1976, Ashgrove Press, p.7-8

[23] Nick McCamley, Avoncliffe: The Secret History of an Industrial Hamlet in War and Peace, 2004, Ex Libris Press, p.77-79

[24] Nick McCamley, Avoncliffe: The Secret History of an Industrial Hamlet in War and Peace, p.90

[25] Dorian Gerhold, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press p.ix

[26] Valerie Bowyer, Along the Canal: The Kennet & Avon from Bath to Bradford-on-Avon, p.8

[27] LJ Dalby, The Wilts and Berks Canal, 1971, Oakwood Press, p.24 and p.63

[28] The Bath Chronicle, 19 March 1835

[29] The Bath Chronicle, 23 February 1832

[30] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, 2007, The Hobnob Press, p.185

[31] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, p.185

[32] The Bath Chronicle, 16 August 1894

[33] Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, 1983, Countryside Books, p.171

[1] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, 1968, David & Charles, p.110-111

[2] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic 1750-1850, p.153

[3] Archibald Robertson, Topographical Survey of the Great Road from London to Bath, 1792, p.70

[4] Archibald Robertson, Topographical Survey of the Great Road from London to Bath, 1792, p.70-71

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 29 January 1818 and Select Reports and Papers of House of Commons, Public works, Vol 38,

The Turnpike Roads in England and Wales, 1836, p.236

[6] Geoffrey N Wright, Roads and Trackways of Wessex, 1988, Ashbourne, p.171

[7] The Bath Chronicle, 23 May 1839

[8] Paul Hindle, Roads and Tracks for Historians, 2001, Phillimore & Co Ltd, p.128

[9] William Albert, The Turnpike Road System in England 1663-1840, 1972, Cambridge University Press, p.143-7

[10] John Copeland, Roads and Their Traffic, p.110

[11] Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, 1988, Paladin, p.354

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 6 October 1785 and 2 March 1786

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 26 November 1938

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 28 March 1833

[15] The Bath Chronicle, 16 April 1840

[16] David Ibberson, The Box Collection, Volume 2, 1989, p.12

[17] Dorian Gerhold, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press p.xiv

[18] Inventory of John Bayly, 8 September 1726, courtesy Anna Grayson

[19] TS Willan, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press p.99-102

[20] Kenneth R Clew, The Kennet & Avon Canal, 1968, David & Charles, p.20

[21] The Bath Chronicle, 14 June 1804

[22] Valerie Bowyer, Along the Canal: The Kennet & Avon from Bath to Bradford-on-Avon, 1976, Ashgrove Press, p.7-8

[23] Nick McCamley, Avoncliffe: The Secret History of an Industrial Hamlet in War and Peace, 2004, Ex Libris Press, p.77-79

[24] Nick McCamley, Avoncliffe: The Secret History of an Industrial Hamlet in War and Peace, p.90

[25] Dorian Gerhold, Road Transport in the Horse Drawn Era, Studies in Transport History, 1996, Scholar Press p.ix

[26] Valerie Bowyer, Along the Canal: The Kennet & Avon from Bath to Bradford-on-Avon, p.8

[27] LJ Dalby, The Wilts and Berks Canal, 1971, Oakwood Press, p.24 and p.63

[28] The Bath Chronicle, 19 March 1835

[29] The Bath Chronicle, 23 February 1832

[30] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, 2007, The Hobnob Press, p.185

[31] Ken Watts, The Wiltshire Cotswolds, p.185

[32] The Bath Chronicle, 16 August 1894

[33] Daphne Phillips, The Great Road to Bath, 1983, Countryside Books, p.171