|

Cecil Lambert's War

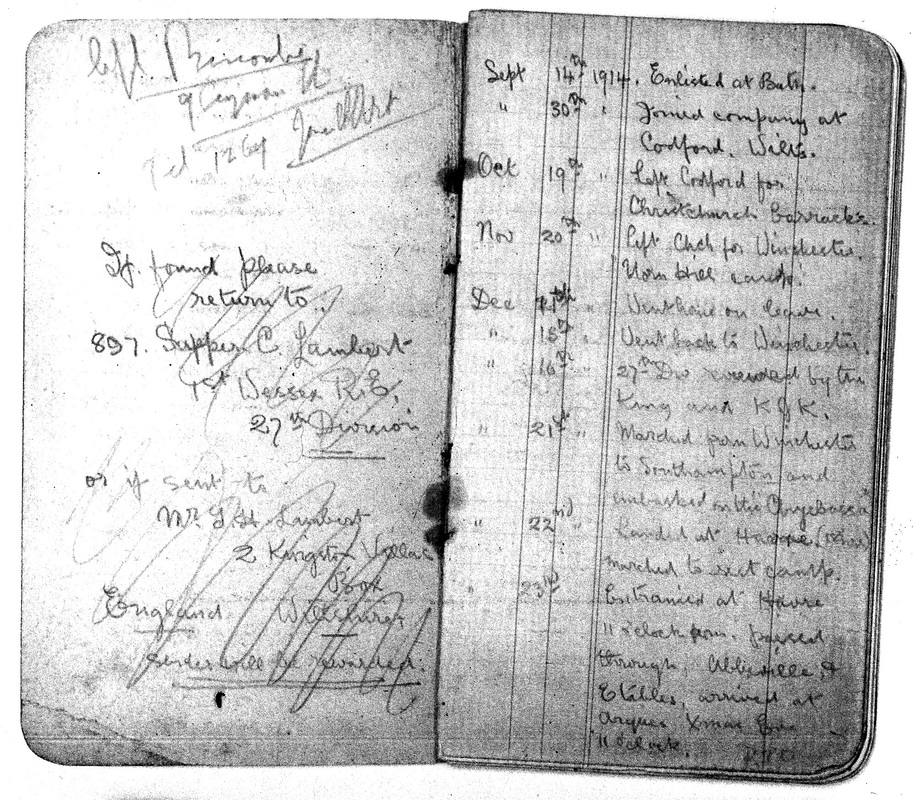

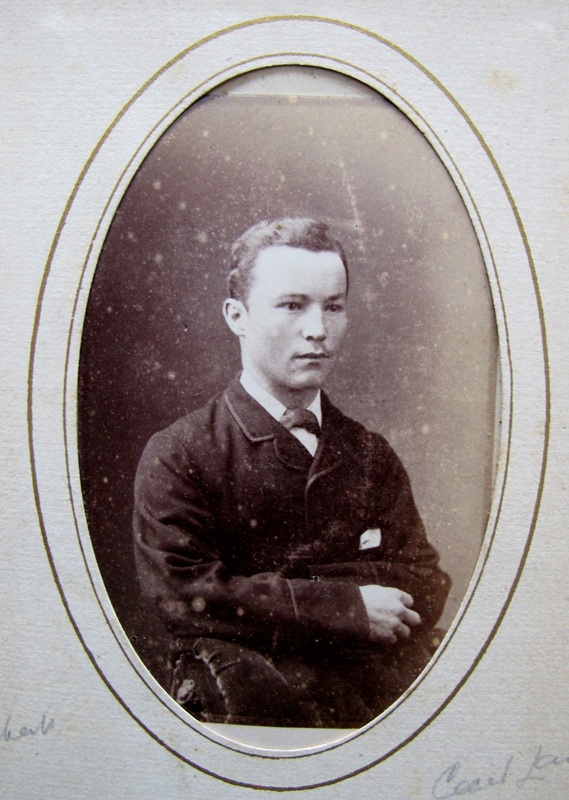

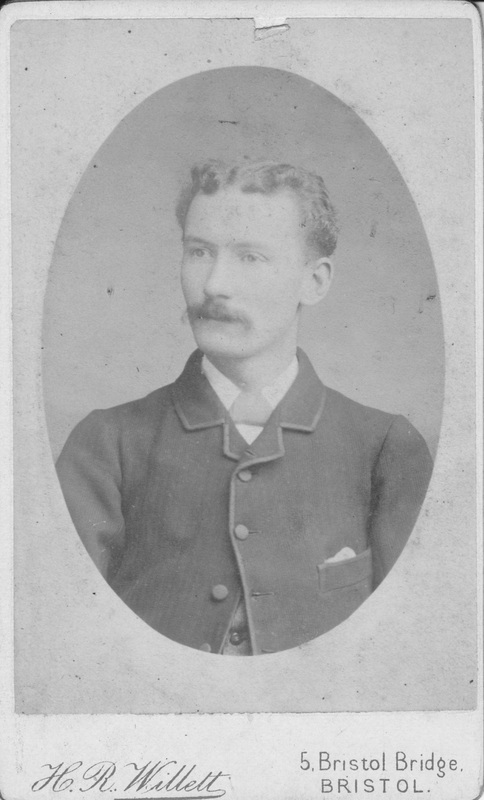

Extracts from Wiltshire History Centre archives These extracts of Cecil's war diary and letters home to his family were researched by the children of Box School, Sycamore class, 2014 under the control and supervision of their teacher, Helen Murphy. Together they have obtained a marvellous insight into the life of a Box soldier during the time of the First World War. Cecil Lambert, former resident of 2 Kingston Villas, Box, has left an amazing legacy for future generations to find out about life during WW1: contemporary, pencil-written diaries and letters home and photos recalling his experiences. Box Primary school has been privileged to study these sources, the pupils undertaking their own research to find out what life was like a hundred years ago for a young man who, like them, had spent his early years at Box primary school. Many thanks are due to the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre in Chippenham, Anna Grayson, Cecil’s niece, for access to the letters and diaries and Margaret Wakefield for access to many of these photos. Their help made this project happen. Cecil Lambert was born in 1895 and went to war in 1914, aged 19. He joined the army as a trench builder with the Wessex Royal Engineers, 1st Division. This is his story, in his words, of his life in the First World War. |

Enlistment

Cecil enlisted on 14th September 1914 with friends from Box: Will Bateman, Art Bradfield, Frank Richards and Allen Chapman; and the next day Jim Browning. He called them the Boxonians and wrote in his diary that they were inspired by the spirit of adventure coupled with a sense of duty. They attended the Drill Hall of the Wessex Royal Engineers in Bath where they had a medical and signed a contract to serve His Majesty for 4 years in any sphere or country to which we might be ordered. For three weeks they were billeted at the Drill Hall to be licked into shape.

On 30th September he set off by train to join up with his Company at Codford, Wiltshire for hard and serious training. On 9th October he was sent to train at Christchurch learning pontoon bridging and rifle shooting and getting an inoculation against malaria in preparation for service abroad. A month later they left for Worm Hill Camp, Winchester, sleeping under canvas in bell tents rather than indoors in barracks. Here they undertook tactical exercises and night manoeuvres with trench digging.

They went home on leave for two days on 11th December to spend time with our relations and friends before saying goodbye to them for perhaps the last time! and Cecil overstayed his time by an extra day before returning to camp on 15th December because they wanted to enjoy My 20th birthday and Will Bateman's 21st and what a day!

Cecil enlisted on 14th September 1914 with friends from Box: Will Bateman, Art Bradfield, Frank Richards and Allen Chapman; and the next day Jim Browning. He called them the Boxonians and wrote in his diary that they were inspired by the spirit of adventure coupled with a sense of duty. They attended the Drill Hall of the Wessex Royal Engineers in Bath where they had a medical and signed a contract to serve His Majesty for 4 years in any sphere or country to which we might be ordered. For three weeks they were billeted at the Drill Hall to be licked into shape.

On 30th September he set off by train to join up with his Company at Codford, Wiltshire for hard and serious training. On 9th October he was sent to train at Christchurch learning pontoon bridging and rifle shooting and getting an inoculation against malaria in preparation for service abroad. A month later they left for Worm Hill Camp, Winchester, sleeping under canvas in bell tents rather than indoors in barracks. Here they undertook tactical exercises and night manoeuvres with trench digging.

They went home on leave for two days on 11th December to spend time with our relations and friends before saying goodbye to them for perhaps the last time! and Cecil overstayed his time by an extra day before returning to camp on 15th December because they wanted to enjoy My 20th birthday and Will Bateman's 21st and what a day!

Royal Review, Embarkation and Christmas 1914

On December 16th, the 27th Division was marched out to the Downs overlooking the town where the whole Division was reviewed by the King. His Majesty was accompanied by Lord Kitchener and General Snow, the 27th Division's General, with the usual trail of attendants, and rode through the ranks on horseback.

Five days later they embarked, marching from Winchester to Southampton, about 14 miles with full packs. The people on the way gave them a good send-off and threw fruit, flowers, chocolates and cigarettes into the road as we passed. The troops were forbidden to pick them up in case they were poisoned but often disobeyed.

They went straight to the docks and embarked on the steamer Chyebassa. On arrival at Le Havre, they marched through the cobbled street of the town to a rest camp for an hour or two’s sleep and then undertook a 24 hour railway journey in crowded cattle trucks labelled 40 hommes, 8 chevaux.

He recounts the strangest Christmas I have ever spent with Christmas meals of bread and bacon (breakfast), bully stew (dinner) and biscuits and jam (tea.). And it was marked by an an unusual memento; he had never had the honour before of receiving a Christmas card from the King. This he sent home for safe-keeping.

Cecil wrote confidently in his letter to his parents that we will enjoy the next (Christmas) altogether I hope and make up for it, little knowing that he would be away for the next four years.

War In Flanders 1915

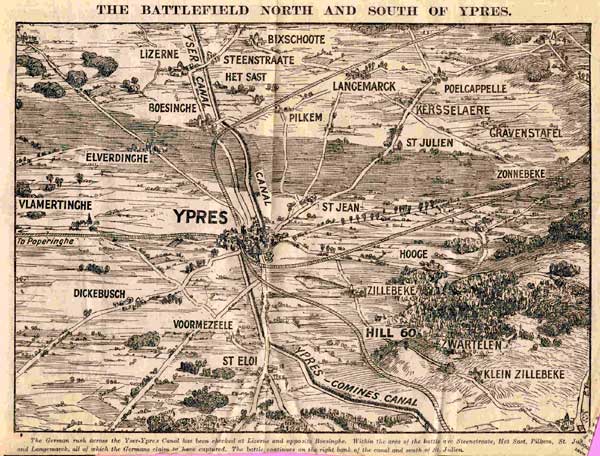

Early January 1915 the Company marched to Dickebusch, 8 miles from Ypres, right in the war zone. The village, although within easy reach of shell fire, was not badly damaged and was still populated by civilians. A rumour circulated that the town was swarming with spies. In January Cecil was on the mat for the second and last time. He slipped away from work and persuaded the cook to provide a dixie of hot water for a wash which incurred a punishment and the loss of three days pay.

On January 18th his diary recorded Went to the trenches. Very lively! It was just a preliminary visit by six sappers including Cecil.[1] There was a terrific noise of gun fire,the screaming and bursting of shells. Now we had our first experience of dodging shrapnel … A little later we entered the deserted streets of a badly battered village which we afterwards found was named Voormayalen... The rifle fire was now very close and it was evident that we should not be able to advance much further... When Lieutenant Carr returned he informed us that we were actually in the front line for a trench ran just outside the walls, manned by infantry.

On December 16th, the 27th Division was marched out to the Downs overlooking the town where the whole Division was reviewed by the King. His Majesty was accompanied by Lord Kitchener and General Snow, the 27th Division's General, with the usual trail of attendants, and rode through the ranks on horseback.

Five days later they embarked, marching from Winchester to Southampton, about 14 miles with full packs. The people on the way gave them a good send-off and threw fruit, flowers, chocolates and cigarettes into the road as we passed. The troops were forbidden to pick them up in case they were poisoned but often disobeyed.

They went straight to the docks and embarked on the steamer Chyebassa. On arrival at Le Havre, they marched through the cobbled street of the town to a rest camp for an hour or two’s sleep and then undertook a 24 hour railway journey in crowded cattle trucks labelled 40 hommes, 8 chevaux.

He recounts the strangest Christmas I have ever spent with Christmas meals of bread and bacon (breakfast), bully stew (dinner) and biscuits and jam (tea.). And it was marked by an an unusual memento; he had never had the honour before of receiving a Christmas card from the King. This he sent home for safe-keeping.

Cecil wrote confidently in his letter to his parents that we will enjoy the next (Christmas) altogether I hope and make up for it, little knowing that he would be away for the next four years.

War In Flanders 1915

Early January 1915 the Company marched to Dickebusch, 8 miles from Ypres, right in the war zone. The village, although within easy reach of shell fire, was not badly damaged and was still populated by civilians. A rumour circulated that the town was swarming with spies. In January Cecil was on the mat for the second and last time. He slipped away from work and persuaded the cook to provide a dixie of hot water for a wash which incurred a punishment and the loss of three days pay.

On January 18th his diary recorded Went to the trenches. Very lively! It was just a preliminary visit by six sappers including Cecil.[1] There was a terrific noise of gun fire,the screaming and bursting of shells. Now we had our first experience of dodging shrapnel … A little later we entered the deserted streets of a badly battered village which we afterwards found was named Voormayalen... The rifle fire was now very close and it was evident that we should not be able to advance much further... When Lieutenant Carr returned he informed us that we were actually in the front line for a trench ran just outside the walls, manned by infantry.

|

January 31st the Company moved into Dickebusch. The visit to the trenches this time was for serious work... we had to proceed cautiously and drop flat in the mud when the flares went up. Arriving at the front line trench we dropped into shell holes immediately... The trenches were in fearful condition, with water in places up to the knees, the duck boards floating on the top.

February was mostly spent consolidating positions. On 4th February, he wrote, Germans broke through during evening; slept in readiness to move. The enemy were repulsed and defences were strengthened with barbed wire some 50 or 60 yards from the German trenches... when things were fairly quiet we crawled over to place them in position and fix them. Every time a flare went up, down we had to go as flat as pancakes in the mud. Most of the Boxonians were still together: Will Bateman, Art Bradfield, Frank Richards and Cecil. On February 25th Art Bradfield was hit in the thigh by a splinter of friendly fire and was lucky in being sent to Blighty! Cecil tells of St Eloi, south of Ypres, being a hot shop where one could always be sure of being under incessant rifle fire. Left: Cecil as a young student |

On 3rd March 1915, after 14 days in the firing line, Cecil's company withdrew from the front line to serve as reserves and he stayed indoors for the day to have a good clean up. He received parcels of food and had a chance to think about Box. What happened at the Scout Company meeting; did you manage to get a new Scoutmaster?

A week later he wrote about enjoying a supper of chips and coffee which was incredibly cheap at only 3d. The weather was cold with bitter winds and snow but he preferred this because as soon as the sun shines I am afraid disease will be rampant for it is bad enough now, at times chronic smells etc. His letter included a request for fags; he has become a confirmed smoker, but really it is a comfort not to be despised out here.

The rest did not last long because St Eloi came under fierce attack. On 15th March Cecil's diary records I sincerely hope it would never be my lot again to see the horror of war as pictured to us this night after the battle. In the infantry trenches the bodies of our men were still lying; some as they had fallen, others propped up in sitting positions with rifles by their sides.

At the end of March he recorded his regular nightly trench work: Sometimes it was pitch dark and we moved in single file holding one another's coat. The guide would give warnings and these were passed back mouth to mouth: Wire overhead! Shell hole on right! Wire under foot! etc

A week later he wrote about enjoying a supper of chips and coffee which was incredibly cheap at only 3d. The weather was cold with bitter winds and snow but he preferred this because as soon as the sun shines I am afraid disease will be rampant for it is bad enough now, at times chronic smells etc. His letter included a request for fags; he has become a confirmed smoker, but really it is a comfort not to be despised out here.

The rest did not last long because St Eloi came under fierce attack. On 15th March Cecil's diary records I sincerely hope it would never be my lot again to see the horror of war as pictured to us this night after the battle. In the infantry trenches the bodies of our men were still lying; some as they had fallen, others propped up in sitting positions with rifles by their sides.

At the end of March he recorded his regular nightly trench work: Sometimes it was pitch dark and we moved in single file holding one another's coat. The guide would give warnings and these were passed back mouth to mouth: Wire overhead! Shell hole on right! Wire under foot! etc

Despatched to Ypres

As Easter approached, his parents sent him a food parcel for a jolly good feed. He had been able to get out of camp to go to an open-air Church of England service the first since leaving England and a football match or rather a scramble between our sappers and drivers, the result was Sappers 8, Drivers 2.

By the end of March he thought that reinforcements were anticipated: The party coming from Christchurch are to make us up to full strength, not to relieve us. I hope they do join us for there are several old school chums amongst them. These men turned out to include Vic Southard, JS, WS, WP and GA from Box.

News had reached him of labour shortages in Box because of men who had enlisted. He wrote to his father: Sorry the trade does not improve. From what I read in the papers other trades are … in want of labour. I can guess how much you miss Bert Moody. He was such a handy chap.

As Easter approached, his parents sent him a food parcel for a jolly good feed. He had been able to get out of camp to go to an open-air Church of England service the first since leaving England and a football match or rather a scramble between our sappers and drivers, the result was Sappers 8, Drivers 2.

By the end of March he thought that reinforcements were anticipated: The party coming from Christchurch are to make us up to full strength, not to relieve us. I hope they do join us for there are several old school chums amongst them. These men turned out to include Vic Southard, JS, WS, WP and GA from Box.

News had reached him of labour shortages in Box because of men who had enlisted. He wrote to his father: Sorry the trade does not improve. From what I read in the papers other trades are … in want of labour. I can guess how much you miss Bert Moody. He was such a handy chap.

Ypres Bombarded |

Life soon altered. On Easter Sunday, 4th April 1915 he marched three hours into Ypres which was bombarded last night .. that is how we spent our Easter holiday.

|

At

this time it was still inhabited by civilians, shops and cafes were

open and goods were displayed in the windows... but the famous

Cathedral and Cloth Hall were very badly battered and so was the

station. At one point they were billeted with the British Expeditionary Force in a YMCA (Young Man’s Christian Association) hostel.

The middle of April 1915 was spent fortifying Ypres, mining and trenching.. We were pretty certain that something was going to happen for every day there seemed to be greater activity on both sides.

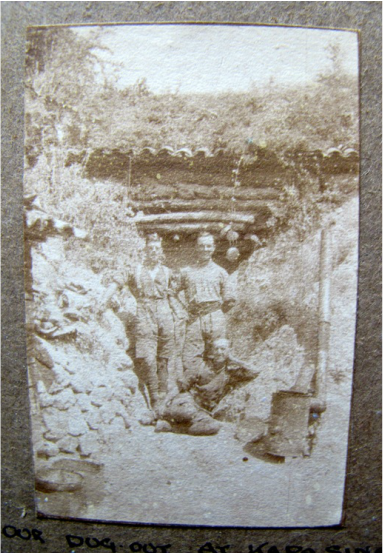

On April 15th he wrote that he was part of a totally unreal world: There are flower beds in the rear of the trenches, and the dug-outs are miniature houses. We have even picked cherries and enjoyed them within fifty yards of the front line. Little crosses mark the place where a Tommy is buried and one especially caught my eye as we passed. It was a well-kept grave and the inscription was “Friend or Foe” - no-one knows but here lies the body of a soldier.

The middle of April 1915 was spent fortifying Ypres, mining and trenching.. We were pretty certain that something was going to happen for every day there seemed to be greater activity on both sides.

On April 15th he wrote that he was part of a totally unreal world: There are flower beds in the rear of the trenches, and the dug-outs are miniature houses. We have even picked cherries and enjoyed them within fifty yards of the front line. Little crosses mark the place where a Tommy is buried and one especially caught my eye as we passed. It was a well-kept grave and the inscription was “Friend or Foe” - no-one knows but here lies the body of a soldier.

|

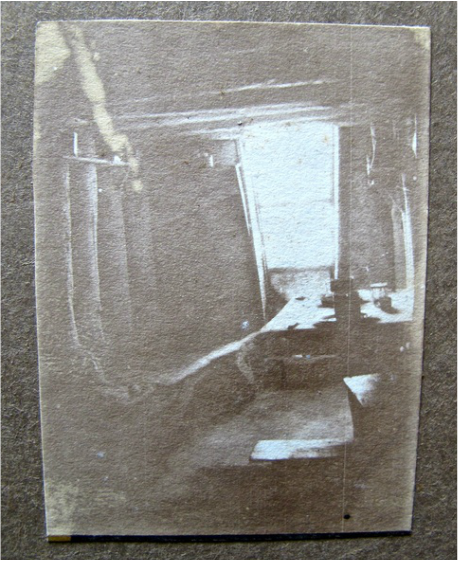

On 19th April he recorded his work in a tunnel with a gallery running right under the enemy trench. At the end of this we had to take turn, in pairs, listening for sounds of enemy working a counter mine... This was a very eerie experience, with only just room to sit on sandbags, side by side, in a hole 4 feet by 2 feet 6 inches for 2 hours, dull rumblings overhead of shell fire and bombs, water constantly dripping and the knowledge that, at any time, the enemy might catch us like rats in a trap.

In this strange position and aided by the light of a candle, I wrote a letter home. As the spring turned into summer, the fighting grew more intense. |

It was plain to everyone that the enemy was preparing a big offensive. On 23rd April two German observation balloons made their appearance. Our huts were spotted and things became so hot that we were ordered to dig ... for protection from splinters.

Battle of Ypres

On 24th April he recorded in his diary: A day to be remembered... bombardment continued .. Ypres in flames; could not get through with message... The Germans made a determined infantry attack on the French at St Julien and drove them back with heavy casualties... I was detailed as Cyclist orderly at the Divisional Headquarters stationed in dug-out in Pontyze (??) woods... It was evident that the situation was critical.

He was given a message to take to the Royal Engineers Headquarters in town by bicycle: Shells came over by the dozen and shrapnel was bursting at intervals all along the road... Arriving at the Menin Bridge, which appeared to be the target … I could see that there would be great difficulty in getting through... the street was blocked by fallen walls and the houses on both sides were blazing furiously. He had to return to base and deliver the message the following morning.

Cecil's letters record passionately the horrors he is living through. On 26th April 1915 he says: There has been very fierce fighting in this quarter the last week. The bombardment has been horrific, burning houses, churches etc; can be seen in all directions.

People in England will never realize what this war is really like. One minute you see a beautiful mansion, the next it is a heap of bricks and mortar. Houses go down like ninepins.

On 29th April 1915 he wrote, The last fortnight has been quite the hottest time we have experienced for shell fire, and at times it has not been safe to stir outside the dug-outs. On May 9th his diary read Our casualties (at Hill 60) must have been terrible and the one doctor with a small staff of Royal Army Medical Corps, who were using a sunken road close by as a dressing station, were overwhelmed with cases.

Battle of Ypres

On 24th April he recorded in his diary: A day to be remembered... bombardment continued .. Ypres in flames; could not get through with message... The Germans made a determined infantry attack on the French at St Julien and drove them back with heavy casualties... I was detailed as Cyclist orderly at the Divisional Headquarters stationed in dug-out in Pontyze (??) woods... It was evident that the situation was critical.

He was given a message to take to the Royal Engineers Headquarters in town by bicycle: Shells came over by the dozen and shrapnel was bursting at intervals all along the road... Arriving at the Menin Bridge, which appeared to be the target … I could see that there would be great difficulty in getting through... the street was blocked by fallen walls and the houses on both sides were blazing furiously. He had to return to base and deliver the message the following morning.

Cecil's letters record passionately the horrors he is living through. On 26th April 1915 he says: There has been very fierce fighting in this quarter the last week. The bombardment has been horrific, burning houses, churches etc; can be seen in all directions.

People in England will never realize what this war is really like. One minute you see a beautiful mansion, the next it is a heap of bricks and mortar. Houses go down like ninepins.

On 29th April 1915 he wrote, The last fortnight has been quite the hottest time we have experienced for shell fire, and at times it has not been safe to stir outside the dug-outs. On May 9th his diary read Our casualties (at Hill 60) must have been terrible and the one doctor with a small staff of Royal Army Medical Corps, who were using a sunken road close by as a dressing station, were overwhelmed with cases.

Longing For Home

By midsummer, Cecil had been on active service for six months and had seen some of the fiercest action of the war. On 17th May 1915 he wrote, There seems little chance of getting a rest, but they will have to soon for the chaps are getting fed up. The company has had more casualties since being in this part than all the time we were at St A-.

The bombardment died down and on May 20th and 21st he had time off to visit the dug-outs of the North Somerset Yeomanry only to hear that his Box colleague Stewart Merrett had been killed a few days before in the bombardment of a trench that I had helped to dig. On May 25th they had Sports in the evening: very enjoyable, the officers giving the prize money. I was successful in getting second for the high jump. He wrote an article about this and send it to the Bath Chronicle, who published it.

He collected lace on bobbins from ruined houses and sent them home as they may be interesting to mother .. will make decent souvenirs.. I have often watched the women making it. But in the very next sentence the horror of the war overtakes the prettiness of the lace: When we first came to this town it was full of civilians, lovely shops were open; in fact it was like a Town in England. Of course parts of it were damaged but now it is a heap of ruins.

By midsummer, Cecil had been on active service for six months and had seen some of the fiercest action of the war. On 17th May 1915 he wrote, There seems little chance of getting a rest, but they will have to soon for the chaps are getting fed up. The company has had more casualties since being in this part than all the time we were at St A-.

The bombardment died down and on May 20th and 21st he had time off to visit the dug-outs of the North Somerset Yeomanry only to hear that his Box colleague Stewart Merrett had been killed a few days before in the bombardment of a trench that I had helped to dig. On May 25th they had Sports in the evening: very enjoyable, the officers giving the prize money. I was successful in getting second for the high jump. He wrote an article about this and send it to the Bath Chronicle, who published it.

He collected lace on bobbins from ruined houses and sent them home as they may be interesting to mother .. will make decent souvenirs.. I have often watched the women making it. But in the very next sentence the horror of the war overtakes the prettiness of the lace: When we first came to this town it was full of civilians, lovely shops were open; in fact it was like a Town in England. Of course parts of it were damaged but now it is a heap of ruins.

All Burnt to Cinders |

A splendid church, just outside here, … is now bear (bare) walls, the interior being entirely burned out and carvings worth thousands all burnt to cinders.

|

He was deeply affected by the scenes he witnessed and he sought to make sense of it out of his own domestic experiences. He sends home dried flowers that were once part of a beautiful, well-kept garden, which brought home to me our own little garden which no doubt now is in the pink of condition.

On May 31st his Company marched south across the Franco-Belgian border. By 14th June he was longing for leave to return home but his company were working close to the German bombing range. We have been busy doing day work just behind the firing line, fortifying ruined farm houses and putting them in a state of defence.

He described the kindness of local families and recounted how, in late June, he arrived at Erquinghem and met Mme Blaem Derensy, the most kindly, sympathetic and good natured of persons I have ever had the pleasure of knowing. She kept a small confectionery shop and lived with her husband, Jules, who worked at a factory in Armentières, and her daughter, Andrea. Cecil wrote to his mother asking her to write to Mme Derensy whose child the same age as his sister, Enid. Mrs Lambert sent a doll to the French child and, amazingly, the mother replied, thanking them for Cecil's great kindness towards us without whom Our poor France would be completely invaded by our enemies.

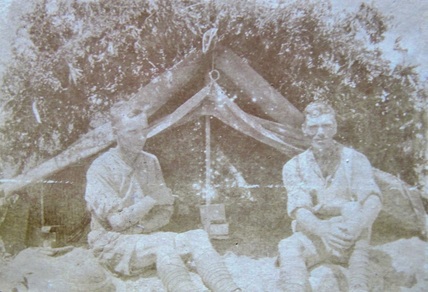

Cecil stayed in the Erquinghem area until 15th September. He was able to relax into a more normal life and he bought a puppy for 1 franc with a bull-dog's face, lop-ears and an unknown capacity for condensed milk.

One job he had at this time was guarding bridge-building stores and ferrying people across a river: He wrote that, after a fortnight of going to the firing line every day, It is a soft job for there is nothing to do except see that the stuff does not “walk”.

On May 31st his Company marched south across the Franco-Belgian border. By 14th June he was longing for leave to return home but his company were working close to the German bombing range. We have been busy doing day work just behind the firing line, fortifying ruined farm houses and putting them in a state of defence.

He described the kindness of local families and recounted how, in late June, he arrived at Erquinghem and met Mme Blaem Derensy, the most kindly, sympathetic and good natured of persons I have ever had the pleasure of knowing. She kept a small confectionery shop and lived with her husband, Jules, who worked at a factory in Armentières, and her daughter, Andrea. Cecil wrote to his mother asking her to write to Mme Derensy whose child the same age as his sister, Enid. Mrs Lambert sent a doll to the French child and, amazingly, the mother replied, thanking them for Cecil's great kindness towards us without whom Our poor France would be completely invaded by our enemies.

Cecil stayed in the Erquinghem area until 15th September. He was able to relax into a more normal life and he bought a puppy for 1 franc with a bull-dog's face, lop-ears and an unknown capacity for condensed milk.

One job he had at this time was guarding bridge-building stores and ferrying people across a river: He wrote that, after a fortnight of going to the firing line every day, It is a soft job for there is nothing to do except see that the stuff does not “walk”.

First Anniversary since Cecil Enlisted |

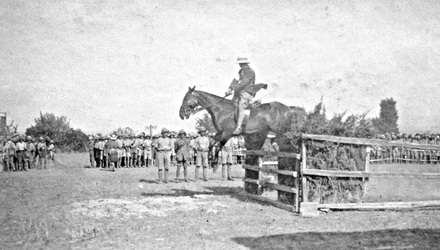

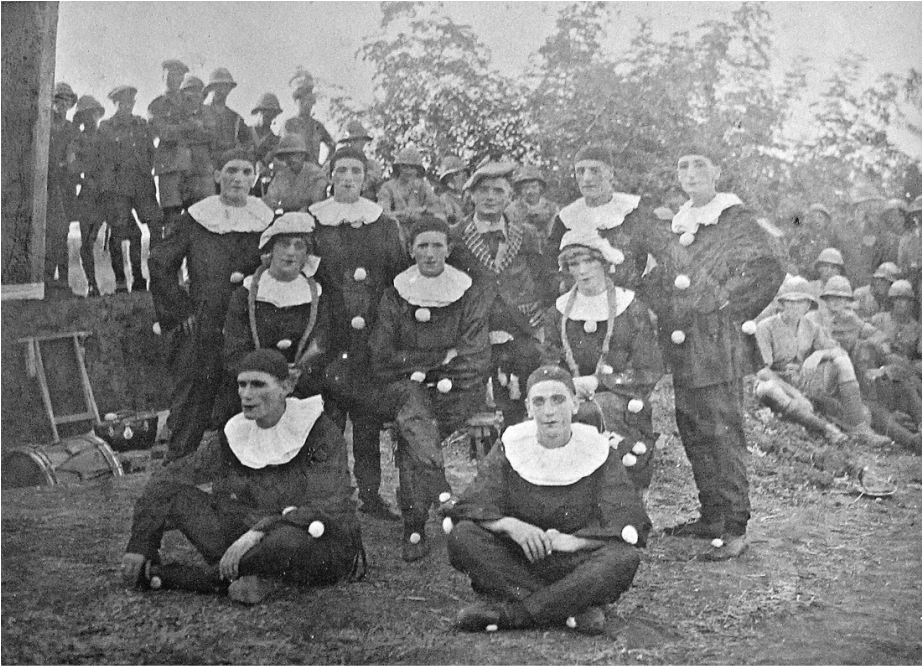

He celebrated the first anniversary since he and his friends had enlisted on 14th September by taking part in a Sports Day. Some of the fellows had togged up in borrowed plumes; one as a race course knut, a couple of females and a bookie.

The next day as they marched out, the villagers lined the pavements and gave us a rousing send-off with cries of bon chance and au revoir. |

Heading to the Somme

By 22nd September 1915 Cecil's company had moved further south into France but still close to the front line. He recorded marches of 12 miles, another 12 miles, train journey of 12 hours in cattle trucks, then 10 miles to Mericourt-L'Abbe, Amiens. There was no hint of leave. It is over a year now since I left you but the time has simply fled by. I wonder how much longer it can last?

His location was much more peaceful and route marches and sentry duties made up most of the news in these letters. He described how they used brushwood for revetting trenches (repairing the sides), as duck-boards, even as ladders. He had a swim in the Canal de la Somme.

On 30th September they shifted three miles to Chuignolees where they dug new trenches. They were still close to the front line, sorting out entanglements in No Man's Land, whilst a party of the 2nd Wessex Field Royal Engineers were busy mining. Box man, Fred Gale, and others were working in a mine deep under the surface when a German counter-mine was blown up, effectively destroying the shaft and burying alive Gale and his 2 companions... the only Box man who joined the two Wessex Companies to be killed and laid to rest on foreign soil.

The closeness of danger encouraged him to get his money sorted out. He wrote to his parents on 9th November that he had transferred £35 of his pay to them to take from it enough to pay for anything I have sent for.

By 22nd September 1915 Cecil's company had moved further south into France but still close to the front line. He recorded marches of 12 miles, another 12 miles, train journey of 12 hours in cattle trucks, then 10 miles to Mericourt-L'Abbe, Amiens. There was no hint of leave. It is over a year now since I left you but the time has simply fled by. I wonder how much longer it can last?

His location was much more peaceful and route marches and sentry duties made up most of the news in these letters. He described how they used brushwood for revetting trenches (repairing the sides), as duck-boards, even as ladders. He had a swim in the Canal de la Somme.

On 30th September they shifted three miles to Chuignolees where they dug new trenches. They were still close to the front line, sorting out entanglements in No Man's Land, whilst a party of the 2nd Wessex Field Royal Engineers were busy mining. Box man, Fred Gale, and others were working in a mine deep under the surface when a German counter-mine was blown up, effectively destroying the shaft and burying alive Gale and his 2 companions... the only Box man who joined the two Wessex Companies to be killed and laid to rest on foreign soil.

The closeness of danger encouraged him to get his money sorted out. He wrote to his parents on 9th November that he had transferred £35 of his pay to them to take from it enough to pay for anything I have sent for.

Officer Froze out of Fear |

In mid October he was on front-line trench duty. He talked understandingly of an officer who froze out of fear in a shell hole:

|

There are many sides of a man's character and it is possible for the very bravest to get into a funk at times. At the end of the month there was some relief from the fighting when the Company was ordered to help local farmers gather in the crop of cider apples. This was indeed a relaxation from the trench work and they played by pelting other sections with apples.

There was a short opportunity to relax. They were let off duties to watch a boxing match between an infantry man, named Cohen, who had been attached to the company, and one of the Company's drivers. The infantry man issued a challenge to anyone in the company for 20 francs a side. The driver took him up and permission was given from the officers for the match to take place. The company interpreter was a boxing expert who acted as referee and an officer was time-keeper. Some of the officers also made up a purse of 60 francs between them, so that the winner would have 60 and the loser 20. The winner was the attached man. Cecil wrote in one of his letters: Both were good boxers and the loser has nothing to be ashamed of.

There was a short opportunity to relax. They were let off duties to watch a boxing match between an infantry man, named Cohen, who had been attached to the company, and one of the Company's drivers. The infantry man issued a challenge to anyone in the company for 20 francs a side. The driver took him up and permission was given from the officers for the match to take place. The company interpreter was a boxing expert who acted as referee and an officer was time-keeper. Some of the officers also made up a purse of 60 francs between them, so that the winner would have 60 and the loser 20. The winner was the attached man. Cecil wrote in one of his letters: Both were good boxers and the loser has nothing to be ashamed of.

Home Leave

By 15th November 1915 Cecil had received news that he would be moving to a new destination and was hopeful of leave before then. In this company there are a lot of men who have roughed it for practically 12 months on active service and have not had any leave, yet the officers can get a third in the same space of time... it is a crying shame especially where Territorials are concerned.

The weather turned into winter and he endured a snow storm for two days. He wrote to his brother, Edward, on 18th November 1915 that we are still enjoying a rest but before long, we shall be trying our luck in another country. He met up with Box men, Tommy Lucas, Alf Ford and Harry Razey. For those who had not been on leave (including Cecil) there was a day's outing to Amiens on November 25th. He was particularly impressed by the cathedral which he compared to Wells. Believing he was due for home leave he started collecting souvenirs, including a revolver stamped Belgian Arms, The Great War, 1914.

On 29th November he got up at 2am, took motor bus and train to Le Havre arriving by 8pm; then a boat to Southampton arriving 8am; and eventually got back in Box at 2.35pm. He wrote in his diary, My pack was full of various souvenirs, shell heads, a French '75 shell case and his revolver. He hadn't been able to tell his parents. It can be imagined with what surprise and delight I was welcomed. He talked of being outwardly cheerful but inwardly dreading the uncertainties of the future.

By 15th November 1915 Cecil had received news that he would be moving to a new destination and was hopeful of leave before then. In this company there are a lot of men who have roughed it for practically 12 months on active service and have not had any leave, yet the officers can get a third in the same space of time... it is a crying shame especially where Territorials are concerned.

The weather turned into winter and he endured a snow storm for two days. He wrote to his brother, Edward, on 18th November 1915 that we are still enjoying a rest but before long, we shall be trying our luck in another country. He met up with Box men, Tommy Lucas, Alf Ford and Harry Razey. For those who had not been on leave (including Cecil) there was a day's outing to Amiens on November 25th. He was particularly impressed by the cathedral which he compared to Wells. Believing he was due for home leave he started collecting souvenirs, including a revolver stamped Belgian Arms, The Great War, 1914.

On 29th November he got up at 2am, took motor bus and train to Le Havre arriving by 8pm; then a boat to Southampton arriving 8am; and eventually got back in Box at 2.35pm. He wrote in his diary, My pack was full of various souvenirs, shell heads, a French '75 shell case and his revolver. He hadn't been able to tell his parents. It can be imagined with what surprise and delight I was welcomed. He talked of being outwardly cheerful but inwardly dreading the uncertainties of the future.

Two and a Half Days Leave |

His leave was very short and he left Box to report back for duty at 11.47am on 3rd December 1915 after only 2½ days.

|

The Company marched south and rumours abounded that they were due to go to Salonica, with the clue our horses being exchanged for mules.

They arrived at Marseilles on 9th December after a long journey in overcrowded cattle trucks. The weather was warm and a good number of the fellows enjoyed some sea bathing. He enjoyed his 21st birthday and Will Bateman's 22nd on 15th December 1915. Cecil got hold of a supply of Japanese bottled ale and Will acquired several pork pies and wonder of wonders, a bottle of Johnny Walker.

He had Christmas Day off and enjoyed the Company's official dinner at a hotel in Marseilles of turkey, beef and Xmas pudding and a concert, which took the form of an impromptu sing-song. And he received a parcel from home. He was still in France on 20th January 1916 although some of the drivers have already embarked.

In total he spent six weeks in Marseilles. During his time there he kept himself fully briefed on all the Box gossip including the

forthcoming marriage of his uncle Alf (AK Lambert) to Miss Bessie Lewis, headteacher of Box Girls' School. Uncle Alf is going to “do the deed” at last, but what a pity we are not home to be present on the day.

They arrived at Marseilles on 9th December after a long journey in overcrowded cattle trucks. The weather was warm and a good number of the fellows enjoyed some sea bathing. He enjoyed his 21st birthday and Will Bateman's 22nd on 15th December 1915. Cecil got hold of a supply of Japanese bottled ale and Will acquired several pork pies and wonder of wonders, a bottle of Johnny Walker.

He had Christmas Day off and enjoyed the Company's official dinner at a hotel in Marseilles of turkey, beef and Xmas pudding and a concert, which took the form of an impromptu sing-song. And he received a parcel from home. He was still in France on 20th January 1916 although some of the drivers have already embarked.

In total he spent six weeks in Marseilles. During his time there he kept himself fully briefed on all the Box gossip including the

forthcoming marriage of his uncle Alf (AK Lambert) to Miss Bessie Lewis, headteacher of Box Girls' School. Uncle Alf is going to “do the deed” at last, but what a pity we are not home to be present on the day.

|

Arrival in Salonica

Cecil left for Salonica, Macedonia, in January 1916 and arrived at the end of the month. He wrote to his parents on 4th February, A week has passed in this new sphere and we have already had a little excitement. His news was that he went into town to have a bath and what a strange experience it was. A circular room with a domed roof and the walls draped in vivid colours. In every room you entered, the baths got hotter and hotter. That is what a Turkish bath is like. He also talked about a recent air raid, It was rather an unpleasant experience for us to wake up and hear bombs whirring through the air and then the explosion, thank goodness it did not last long, a few fires sprung up in town but no damage was done in the camp although one or two came quite close. Healthcare was an important issue for the arriving soldiers. Cecil found the change of climate gave him a bad cough for a few days. On Sunday 20th February 1916 he had the day off because he had received a dose of immunisation against cholera. It was not nearly so fearful as the last lot. He had a clean change of clothes, washed his dirty clothes in a stream using a horse dandy brush and was able to reflect on his situation. The weather was changeable, sunny then ice cold and foggy but no snow in the valley, rain instead. |

There were lots of animals; ponies and donkeys as there is no railway. There was one interesting item, Wild yellow and blue crocuses are more common than buttercups. He had spent a day and a half marching over high country In the clouds practically. He wrote about the villages being small and dilapidated, picturesque with quaint minarets. The country was as desolate as when St Paul pottered about here.

On 1st March 1916 he wrote a letter to his younger sister, Flo, about the countryside. Foxes were very common and that there were supposed to be wolves. Vultures, hawks and owls were also common but there were not very many small birds – he suspected because of the vultures. He wondered about what the civilians would do once peace was restored because there were apparently no industries in the country and the main money-maker was sheep and goat rearing and tilling with old-fashioned implements.

Reflections From Mesopotamia

On 1st April 1916 he wrote again to Flo to tell her that, The Germans have delivered one of their greatest attacks and have been beaten, ignominiously. He hoped that it is only a matter of time before they are defeated. For him personally, though, things had been quiet, even though there was an air raid nearby, luckily a safe distance away.

He had received one of his heart's desires, a pocket chess set. He had played the brother of the lady's champion of Bath, a pretty good player, who has whacked him several times. Apart from that he has very little to write about.

By the spring of 1916, Cecil had been in active service for 18 months. No longer was he a raw recruit, smoking cigarettes and a pipe for the first time. Now he was battle-hardened soldier who had seen service in Flanders, France and Salonica. His attitude to life and the war had changed him, as reflected in his letter of 17th April 1916 to his parents: Have you had any more conscientious objectors to deal with? I thought we were free of such idiots in our little sphere. Should like to have Mr F(red) Neate here and tell him what I think of him and his kind.[2] Such men as that should be jumped into a suit of khaki at once and given no option. They ought to be presented with cast iron hearts to wear round their necks on a chain.

On 1st March 1916 he wrote a letter to his younger sister, Flo, about the countryside. Foxes were very common and that there were supposed to be wolves. Vultures, hawks and owls were also common but there were not very many small birds – he suspected because of the vultures. He wondered about what the civilians would do once peace was restored because there were apparently no industries in the country and the main money-maker was sheep and goat rearing and tilling with old-fashioned implements.

Reflections From Mesopotamia

On 1st April 1916 he wrote again to Flo to tell her that, The Germans have delivered one of their greatest attacks and have been beaten, ignominiously. He hoped that it is only a matter of time before they are defeated. For him personally, though, things had been quiet, even though there was an air raid nearby, luckily a safe distance away.

He had received one of his heart's desires, a pocket chess set. He had played the brother of the lady's champion of Bath, a pretty good player, who has whacked him several times. Apart from that he has very little to write about.

By the spring of 1916, Cecil had been in active service for 18 months. No longer was he a raw recruit, smoking cigarettes and a pipe for the first time. Now he was battle-hardened soldier who had seen service in Flanders, France and Salonica. His attitude to life and the war had changed him, as reflected in his letter of 17th April 1916 to his parents: Have you had any more conscientious objectors to deal with? I thought we were free of such idiots in our little sphere. Should like to have Mr F(red) Neate here and tell him what I think of him and his kind.[2] Such men as that should be jumped into a suit of khaki at once and given no option. They ought to be presented with cast iron hearts to wear round their necks on a chain.

On 24th April 1916 he wrote reflectively to his brother, Herbert, who was serving in India, about the wilds of Salonica with its mud-hutted and tumble-down villages... devoid of life and industry, except for the tortoises and descendants of vermin who tempted Adam. As fellow soldiers he reminisced about army life. He had enjoyed a much easier time since he left France but was bored. He asked Does a serviceman live or does he just exist … on bully and biscuits? The war was all so unreal.

He talked about his younger brother, Edward, who had received a letter from GWR (Great Western Railways) cancelling his attestment (oath of loyalty to serve the railways) but he is not strong enough for army life. And he reminisced that A year ago last Sunday (Easter Sunday) we were marching from Reningeist to world-famed Ypres and so commenced the few weeks which will undoubtedly form the outstanding feature in our careers as soldiers.

He was in light-hearted mood. His long letter ended with a verse that the Wessex Signals had composed about Salonica:

He talked about his younger brother, Edward, who had received a letter from GWR (Great Western Railways) cancelling his attestment (oath of loyalty to serve the railways) but he is not strong enough for army life. And he reminisced that A year ago last Sunday (Easter Sunday) we were marching from Reningeist to world-famed Ypres and so commenced the few weeks which will undoubtedly form the outstanding feature in our careers as soldiers.

He was in light-hearted mood. His long letter ended with a verse that the Wessex Signals had composed about Salonica:

|

There's a little place out East called Salonique

Where they're sending British Tommies every week. When you view it from the sea it's a fine sight, I'll agree And you think you'll have a spree At Salonique. When you're dumped upon the quay at Salonique And the smell that meets you there seems to speak, You begin to feel quite glum And wish you had not come. For there's every kind of hum At Salonique. |

There's lots of little camps round Salonique

Filled with French and British Tommies, hard as teak. And the Kaiser and his pack Will find when they attack There's a nut they cannot crack At Salonique. |

On Good Friday he wrote to his parents on his day off. He had previously been granted a higher trade rating and received a pay rise of 4d a day, making his total pay 2s.10d a day. Now he was promoted to Lance Corporal, and received a further 4d per day.

Because of the heat in Salonica, they were to be issued with sombreros and short knicks and, even as a Territorial unit, they were considered to be the smartest Company in the Division ahead of the Regulars. Then his mind returned to home: Sorry to hear that the trade does not improve. If you think it for the best why don't you give up the (stone) yard? But I suppose the difficulty of getting another business or occupation at this time would be pretty great.

On June 23rd 1916 he had moved again and was now by the sea in a small cove surrounded by high hills. The days were so hot that they had to march at night starting at sunset. He marched at the head of the column in charge of a party of 12 men carrying pump equipment, responsible for supplying water at the end of each day's march. He thought the weather was almost hot enough to boil the sea. A month later he told his sister, Flo, that they were taking a daily dose of quinine (for malaria) and urged her to Cheer up, it is nearly over! To his younger sister, Kathleen, he wrote of nasty flies that bite and snakes, some over 6 feet long.

The regularity of the correspondence enabled Cecil to keep in touch with his family but it caused concern when there was a delay. On 10 August 1916 he had just received his parents letter of July 23rd. He was sorry that he hadn’t replied earlier and had caused some worry. His brother, Frank, had written about shortages of food but catering for a family of about four million is a big thing and pudding every day is out of the question. Recently they had bacon for breakfast, roast meat and a vegetable for dinner, rice for tea nearly every day. If we stay here long we shall be ready for market!

And he had news to tell them of other Box soldiers: Alf Ford of the 2nd Company has just popped in. He and the other Box chaps in that Company are quite well. He told me that Tommy Lucas actually laughed yesterday. Great Scott, I would have given a fortune to have seen it.

Because of the heat in Salonica, they were to be issued with sombreros and short knicks and, even as a Territorial unit, they were considered to be the smartest Company in the Division ahead of the Regulars. Then his mind returned to home: Sorry to hear that the trade does not improve. If you think it for the best why don't you give up the (stone) yard? But I suppose the difficulty of getting another business or occupation at this time would be pretty great.

On June 23rd 1916 he had moved again and was now by the sea in a small cove surrounded by high hills. The days were so hot that they had to march at night starting at sunset. He marched at the head of the column in charge of a party of 12 men carrying pump equipment, responsible for supplying water at the end of each day's march. He thought the weather was almost hot enough to boil the sea. A month later he told his sister, Flo, that they were taking a daily dose of quinine (for malaria) and urged her to Cheer up, it is nearly over! To his younger sister, Kathleen, he wrote of nasty flies that bite and snakes, some over 6 feet long.

The regularity of the correspondence enabled Cecil to keep in touch with his family but it caused concern when there was a delay. On 10 August 1916 he had just received his parents letter of July 23rd. He was sorry that he hadn’t replied earlier and had caused some worry. His brother, Frank, had written about shortages of food but catering for a family of about four million is a big thing and pudding every day is out of the question. Recently they had bacon for breakfast, roast meat and a vegetable for dinner, rice for tea nearly every day. If we stay here long we shall be ready for market!

And he had news to tell them of other Box soldiers: Alf Ford of the 2nd Company has just popped in. He and the other Box chaps in that Company are quite well. He told me that Tommy Lucas actually laughed yesterday. Great Scott, I would have given a fortune to have seen it.

War Drags On

On 16 July he wrote to his brother, Bert, complaining of the flies and mosquitoes but we are within easy reach of the sea and that is a great pleasure. He wrote, It is nine months now since we saw any fighting. It hardly seems possible. We were then in the Somme district. He recalled home in nostalgic mode: I suppose we shall see great changes in everything and everybody when we return and Army life is bound to make a difference in ourselves.

By 18 July his mind had turned again to his father's building trade, hope you will get the Alcombe job, it would keep things (going) along a bit. The problem as he saw it was farmers paying 10½d an hour for hay-making; what a price. He has time to reflect on these matters because There is nothing doing here, we almost forget we are taking part in a world-wide war. On 2 August 1916 another milestone was approaching. He wrote to Flo, In two days we shall reach the second anniversary of the war and from the news we have had lately we can enter into the third year hopefully and smiling. Two years ago! I shall never forget that Bank Holiday and the rush for the evening papers … and reading the declaration of war.

He has heard that his brother Ed's time (as a civilian) was nearly up and he enclosed a note giving him a few tips from an old stager.[3] He has heard from Mme Derensy. The Germans bombarded the village and she has been compelled to shift .. Poor woman. People in England will never realize what they have had to put up with in France.. She and the little girl are refugees in their own country.

On 23rd September 1916 Cecil wrote to his parents with news of his colleagues, We have joined the Company again and I have seen Frank (his cousin Francis Richards) who was in hospital when we arrived but has since returned. .. Jim Browning and Vic Southard are both in dock (unwell). It has been a bad spell for illness lately... perhaps the change of weather has something to do with it … for it has suddenly become cold and damp … with a very cold wind blowing and as I write this our bivvy is rocking to and fro like a ship at sea... Have just been interrupted to help the Sergeant issue out the rum and cigarettes, and jolly thankful the chaps were to get it on a night like this.

He told them that they had enjoyed a service from the Chaplain, the first for some months, taking for his text, What think ye of Christ; whose son is he?

On 16 July he wrote to his brother, Bert, complaining of the flies and mosquitoes but we are within easy reach of the sea and that is a great pleasure. He wrote, It is nine months now since we saw any fighting. It hardly seems possible. We were then in the Somme district. He recalled home in nostalgic mode: I suppose we shall see great changes in everything and everybody when we return and Army life is bound to make a difference in ourselves.

By 18 July his mind had turned again to his father's building trade, hope you will get the Alcombe job, it would keep things (going) along a bit. The problem as he saw it was farmers paying 10½d an hour for hay-making; what a price. He has time to reflect on these matters because There is nothing doing here, we almost forget we are taking part in a world-wide war. On 2 August 1916 another milestone was approaching. He wrote to Flo, In two days we shall reach the second anniversary of the war and from the news we have had lately we can enter into the third year hopefully and smiling. Two years ago! I shall never forget that Bank Holiday and the rush for the evening papers … and reading the declaration of war.

He has heard that his brother Ed's time (as a civilian) was nearly up and he enclosed a note giving him a few tips from an old stager.[3] He has heard from Mme Derensy. The Germans bombarded the village and she has been compelled to shift .. Poor woman. People in England will never realize what they have had to put up with in France.. She and the little girl are refugees in their own country.

On 23rd September 1916 Cecil wrote to his parents with news of his colleagues, We have joined the Company again and I have seen Frank (his cousin Francis Richards) who was in hospital when we arrived but has since returned. .. Jim Browning and Vic Southard are both in dock (unwell). It has been a bad spell for illness lately... perhaps the change of weather has something to do with it … for it has suddenly become cold and damp … with a very cold wind blowing and as I write this our bivvy is rocking to and fro like a ship at sea... Have just been interrupted to help the Sergeant issue out the rum and cigarettes, and jolly thankful the chaps were to get it on a night like this.

He told them that they had enjoyed a service from the Chaplain, the first for some months, taking for his text, What think ye of Christ; whose son is he?

Peace, 1918 and Russia, 1919

As the war continued in other arenas, Cecil had little news to tell his parents and relatives and his letters dwindled but never stopped altogether. On 8th June 1918 he wrote to Flo about a visit he had made to the town of Salonica. The roads are wonderfully improved since we came up. Every nation in the world seems to be represented in the civil population. He talked of the Jewish flappers who were of course all arranged in their Sunday best. Some were quite good looking too !! … But Salonique is certainly not the place to spend an holiday after the war.

By August 28th 1918 his peaceful time had been interrupted: This is a hot shop for shell fire, the hottest we have been in for a long time... This morning I was out with a party and drawing a burst of shelling. One pitched within 4 yards of us. Luckily we were under the shelter of a mud wall and that stopped the splinters... I am heartily fed up with war.

The war ended on 11 November 1918 but Cecil still had work to do in the army and was despatched to Russia. 28 January 1919 Cecil wrote to his cousin Marjorie (probably Marjorie Collett) giving an outline of my wanderings since leaving dear old Blighty on December 14th. He retold his adventures in outline, possibly a way of trying to put such momentous events behind him. His memory of the first Christmas abroad prompted him to talk of the present one in 1918 my fifth in service … and I think it can now be safely said, the last. He remembered things that he had not previously mentioned for fear of alarming his parents: being sick on the transport boat having eaten “Xmas dinner” .. hot water with bully thrown in as make-weight.

As the war continued in other arenas, Cecil had little news to tell his parents and relatives and his letters dwindled but never stopped altogether. On 8th June 1918 he wrote to Flo about a visit he had made to the town of Salonica. The roads are wonderfully improved since we came up. Every nation in the world seems to be represented in the civil population. He talked of the Jewish flappers who were of course all arranged in their Sunday best. Some were quite good looking too !! … But Salonique is certainly not the place to spend an holiday after the war.

By August 28th 1918 his peaceful time had been interrupted: This is a hot shop for shell fire, the hottest we have been in for a long time... This morning I was out with a party and drawing a burst of shelling. One pitched within 4 yards of us. Luckily we were under the shelter of a mud wall and that stopped the splinters... I am heartily fed up with war.

The war ended on 11 November 1918 but Cecil still had work to do in the army and was despatched to Russia. 28 January 1919 Cecil wrote to his cousin Marjorie (probably Marjorie Collett) giving an outline of my wanderings since leaving dear old Blighty on December 14th. He retold his adventures in outline, possibly a way of trying to put such momentous events behind him. His memory of the first Christmas abroad prompted him to talk of the present one in 1918 my fifth in service … and I think it can now be safely said, the last. He remembered things that he had not previously mentioned for fear of alarming his parents: being sick on the transport boat having eaten “Xmas dinner” .. hot water with bully thrown in as make-weight.

He recalled the journey to Russia, embarking on HMT INDARRA, an Australian SS, on January 11th1919... The passage through the Dardenelles was very interesting for we saw one of the famous landing places with plenty of wrecks still sticking out of the water... Constantinople looks a fine town from the harbour. We were anchored there for about six hours.

He went on to tell of his time in Russia in detail: On January 15th we had our first look at Russia and the snow-tipped hills... On the 16th we landed at Batoum (Georgia) … the town was a dirty place .. then a journey of two days. 7th Dec and we arrived at our destination, Tiflis … half way between the Black Sea and the Caspian.

He had three week's leave in England and During my absence the Company has altered a great deal, several of my pals have gone and we lost our Major who died of illness a few days after landing in this country. He was the last of our original officers who came out with us in 1914.Two days after rejoining I was promoted to Corporal .. and given a job in the Company office to understudy the Pay Sergeant who is expecting to go home shortly... Roll on Blighty and the Peace Concert. And finally it was all over and Cecil returned to Box.

He went on to tell of his time in Russia in detail: On January 15th we had our first look at Russia and the snow-tipped hills... On the 16th we landed at Batoum (Georgia) … the town was a dirty place .. then a journey of two days. 7th Dec and we arrived at our destination, Tiflis … half way between the Black Sea and the Caspian.

He had three week's leave in England and During my absence the Company has altered a great deal, several of my pals have gone and we lost our Major who died of illness a few days after landing in this country. He was the last of our original officers who came out with us in 1914.Two days after rejoining I was promoted to Corporal .. and given a job in the Company office to understudy the Pay Sergeant who is expecting to go home shortly... Roll on Blighty and the Peace Concert. And finally it was all over and Cecil returned to Box.

Postscript

Cecil was mentioned in despatches in 1918 (diploma signed by Winston Churchill) and was awarded the French Medaille d'Honneur en bronze avec gloires.

After the war, he returned to live in Box. He was active on Box Parish Council for forty years, represented the District Council, was chairman of the local Liberal Association, and the Box Playing Fields committee, and President of Box Cricket Club and Box branch of the British Legion. But it is through his fabulous diary and letters that we really get to know the man himself, his kindness and his commitment to family and friends.

Source

Cecil's full diary and his letters home are available to see at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, Chippenham together with some photos that he took in service.

Cecil was mentioned in despatches in 1918 (diploma signed by Winston Churchill) and was awarded the French Medaille d'Honneur en bronze avec gloires.

After the war, he returned to live in Box. He was active on Box Parish Council for forty years, represented the District Council, was chairman of the local Liberal Association, and the Box Playing Fields committee, and President of Box Cricket Club and Box branch of the British Legion. But it is through his fabulous diary and letters that we really get to know the man himself, his kindness and his commitment to family and friends.

Source

Cecil's full diary and his letters home are available to see at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, Chippenham together with some photos that he took in service.

Footnotes

[1] Cecil describes sapping as a form of trench digging in exposed position. A trench was dug at right angles to the existing front line aimed directly at the enemy. They were generally used as listening posts.

[2] Fred Neate refused to fight on moral grounds and he became a stretcher-bearer on the front line, one of the most dangerous jobs of all.

[3] This is particularly pointed because Edward died of wounds two years later on 13th July 1919.

[1] Cecil describes sapping as a form of trench digging in exposed position. A trench was dug at right angles to the existing front line aimed directly at the enemy. They were generally used as listening posts.

[2] Fred Neate refused to fight on moral grounds and he became a stretcher-bearer on the front line, one of the most dangerous jobs of all.

[3] This is particularly pointed because Edward died of wounds two years later on 13th July 1919.