|

Witches, Quakers and Chapels:

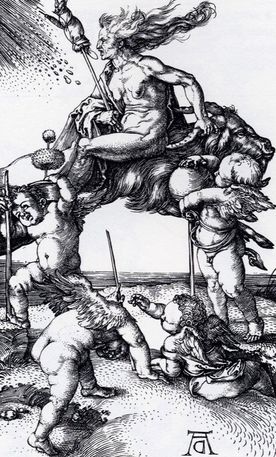

Religion in Georgian Box Alan Payne February 2019 The Witchcraft Act of 1735 made it a crime for anyone to practise witchcraft or to claim that they had magical powers. By outlawing the practice, the act abolished the hunts for witches and the trials that blighted the years of the English Civil War. But it is hard for us to interpret whether this shows increased religious morality or continuing medieval mysticism. Contemporaries had no doubt and frequently referred to falling attendance in churches, the rise of secular enlightenment and declining respect for the clergy in the Georgian period. A Box resident, John Bowdler, wrote in 1798 believing he was witnessing the eradicating of Christianity in this entire quartile of the world.[1] Right: Die Hexe, Depiction of Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat, by Albrecht Durer, in about 1500 (courtesy Wikipedia) |

Church of England

The Established Church was much more than a place of worship in the Georgian period. People were registered in parishes, rather than villages, and the parish authorities recorded births, deaths and marriages, controlled rates for the provision of social welfare, road maintenance and law and order and was the main source of information. Outside their parish people were foreigners, liable to deportation in adverse times and dependent on the parish Poor Law in old age and illness.[2]

There was a desire after the Civil War to increase the level of education of the clergy by employing graduates, rather than the person appointed by the rector's nomination. In Box all vicars came from Oxbridge after Walter Bushnell's appointment in 1644.[3] They were appointed after a rigorous Classical examination involving the translation of the Gospel of St Matthew into Greek and Latin. Literacy was important for the vicar and parish clerk to record the Church Registers of marriages, deaths and baptism, administering wills, the needs of the Church Court and supervising the work of the Overseers of the Poor. But, at the same time, the status of the minister in the area diminished because they were no longer one of the few literate professionals, their role challenged by a growing number of lawyers, medical people and wealthy merchants.

Clerical pluralism (vicars responsible for several parishes) and absenteeism existed during the incumbency of several of Box's vicars, including George Miller (1707 - 1740), John Morris (1740 - 1774) and Samuel Webb (1774 - 1797).[4] Some of these lived in Box, others didn't, preferring to employ a curate for local theological duties. Henry Hawes (of Wilton and Wadham College, Oxford) was rector of Little Langford and curate for the churches of Box and Bathford.[5] He was described in 1783 by

Dr Thomas Eyre, curate of Fovant, Wiltshire as: poor Hawes, with a family of six children and as looking like a primitive Christian, which is not much the line of the clergy these days.

The Established Church was much more than a place of worship in the Georgian period. People were registered in parishes, rather than villages, and the parish authorities recorded births, deaths and marriages, controlled rates for the provision of social welfare, road maintenance and law and order and was the main source of information. Outside their parish people were foreigners, liable to deportation in adverse times and dependent on the parish Poor Law in old age and illness.[2]

There was a desire after the Civil War to increase the level of education of the clergy by employing graduates, rather than the person appointed by the rector's nomination. In Box all vicars came from Oxbridge after Walter Bushnell's appointment in 1644.[3] They were appointed after a rigorous Classical examination involving the translation of the Gospel of St Matthew into Greek and Latin. Literacy was important for the vicar and parish clerk to record the Church Registers of marriages, deaths and baptism, administering wills, the needs of the Church Court and supervising the work of the Overseers of the Poor. But, at the same time, the status of the minister in the area diminished because they were no longer one of the few literate professionals, their role challenged by a growing number of lawyers, medical people and wealthy merchants.

Clerical pluralism (vicars responsible for several parishes) and absenteeism existed during the incumbency of several of Box's vicars, including George Miller (1707 - 1740), John Morris (1740 - 1774) and Samuel Webb (1774 - 1797).[4] Some of these lived in Box, others didn't, preferring to employ a curate for local theological duties. Henry Hawes (of Wilton and Wadham College, Oxford) was rector of Little Langford and curate for the churches of Box and Bathford.[5] He was described in 1783 by

Dr Thomas Eyre, curate of Fovant, Wiltshire as: poor Hawes, with a family of six children and as looking like a primitive Christian, which is not much the line of the clergy these days.

|

The wealth of Box vicars in the 1700s and early 1800s differentiated them sharply from the majority of their parishioners. Their wealth came from land including their entitlement to occupy glebe land and annual tithe income. In Box, the glebe land is shown on Francis Allen's map of 1626 next door to the church, marked as VICRE (now known as Box House).

But most of their income was from the tithes and customary payments into which the tithes had been commuted. The 1840 Tithe Apportionment records specify that William Brook Northey, impropriate (lay) rector of Box, received £481.16s.4d from this source and that Rev HDCS Horlock received £380 plus an additional £28.3s.8d. |

We get a good description of the lifestyle of the vicar from the 1783 Terrier (inventory) of the church.[6] The vicarage comprised Box House, 2 parlours, a kitchen, 3 pantries with bedchambers and garretts above. A brewhouse adjoining. A stables yard with stable, coach house, granary, coal house and 2 woodhouses. A walled garden about 1 acre. A house on the south-east side of the churchyard with coal house and woodhouse. All buildings of stone and in good repair. The possessions of the vicar were significant although most were for church, not personal, use: silver flagon, chalice, and 2 salvers - This plate was given to the parish of Box by Richard Musgrave of Haselbury, Esq and Dame Rachel Speke, his wife. The vicar's vestments were made of superfine cloth with silk fringe.

Having said all this, it was social and cultural differences that separated Box's clergy and general laity. The intrusion of the church and the vicar into the everyday lives of residents through the tithe gave the clergy undue influence and seeming superiority. The wealth and education of the clergy ranked them as gentry, second-only to the status of the lord of the manor.[7]

Having said all this, it was social and cultural differences that separated Box's clergy and general laity. The intrusion of the church and the vicar into the everyday lives of residents through the tithe gave the clergy undue influence and seeming superiority. The wealth and education of the clergy ranked them as gentry, second-only to the status of the lord of the manor.[7]

|

Quakers in Box

The area around Box was full of licensed Quaker Meeting houses, including four private houses at Bathford, at Shockerwick and one Quaker Conventicle house at Ditteridge.[8] However, we know that several other individual members of the Friends lived in Box because of the records kept by the Society. The Friends' Burial Ground (at times called Paradise Close) existed just beyond Bathford Bridge, near the present Batheaston Roundabout of 1993. There were 241 Quaker burials recorded there in the period 1703 - 1837.[9] Box residents include Thomas Collett, buried 5 November 1731, Elizabeth Fifield, buried November 1739 and Nathaniel Vallis buried 17 April 1799. |

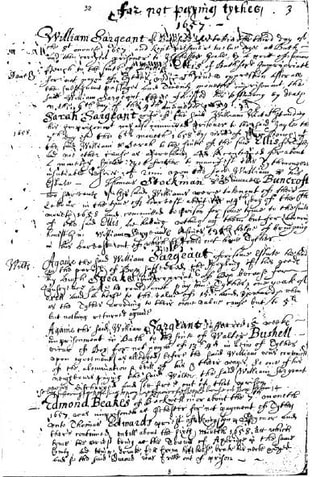

The Society of Friends also kept a tribute book to their wronged members, the Book of Sufferings, which mentions a Box resident.[10] William Sargeant, a farmer, who was recorded on three occasions as having failed to pay towards the repair of Box Church and being fined in the 1650s. William, his wife Sarah and two servants, Thomas Stockman and Samuel Buncroft, appear to have been in frequent difficulties with the authorities for their beliefs.

|

The Sufferings report of 1658 reads, with original spellings:

William Sargeant for some estate he had in the parish of Box suffered the spoyling of his goods by Hugh Speake Improprietor of Box because for conscyence sake he could not pay his Tythes, one yoake of oxen and a horse to the value of £15 and upwards when as the Tythes according to their own value came but to £5 but nothing returned again. Again the said William Sargeant suffered 15 weeks imprisonment in Bath to the suite of Walter Bushell vicar of Box for non payment of 13s.4d in lieu of Tythes upon agreement (as alledged) before the said William was convinced of the abomination and evill of his and their ways. So one of his neighbours paying the said Walter the said William Sargeant was discharged and sett free out of that prison so his suffering for refusing to pay to the repairs of the steeplehouse. William died on 6 April the following year in prison in Ilchester Gaol during 20 month's sentence for non-payment of Bathford tithes. No more is known of witchcraft in Box. Right: Commander AS Craig, The Book of Sufferings (courtesy The Quakers and Bathford, Bathford Local History Society, p.36) |

John Wesley

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, preached regularly throughout the area.[11] His first visit to Bath was in April 1739 preaching the free grace of God to a huge crowd estimated as about a thousand people.[12] In June 1739 he had a famous confrontation with Beau Nash in Bath.[13] He and his brother Charles came many times, opening the first chapel in Avon Street in 1743 and laying the foundation stone of the New King Street Chapel in 1777.

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, preached regularly throughout the area.[11] His first visit to Bath was in April 1739 preaching the free grace of God to a huge crowd estimated as about a thousand people.[12] In June 1739 he had a famous confrontation with Beau Nash in Bath.[13] He and his brother Charles came many times, opening the first chapel in Avon Street in 1743 and laying the foundation stone of the New King Street Chapel in 1777.

|

The nonconformist movement appealed to Box’s poorer people as depicted by Wesley’s hymn, Our Saviour by the rich unknown, Is worshipped by the poor alone. The chapel movement with tightly-knitted congregations and inspirational fervour appealed to weavers and quarry workers seeking to better their living standards and wanting solace from the hardship of their working lives.

Before his death in 1791 John Wesley held missions in Wiltshire at Bradford-on-Avon, Trowbridge, East Tytherton (near Chippenham) and Seend.[14] On his journeys between London and the West Country he would have travelled through Kingsdown but there is no record of his having preached in the parish. The itinerant preacher, George Whitefield, took the local initiative after he was banned from Bristol in 1740, preaching with simple faith and great enthusiasm in the open air, targeting farm labourers and low-skilled workers like quarrymen. Often the preacher spoke from dawn to dusk to those who cared to listen. His protégé, Calvinist preacher Cornelius Winter, preached widely throughout Gloucestershire and Wiltshire during the years 1770 to 1778 and it may be that his evangelism was of influence in Box.[15] |

Meeting House Certificates

If there was enough interest, nonconformist meetings were organised in the private dwelling houses of supporters. In 1802

a house belonging to Jacob Ford was certificated at Middlehill.[16] The Roe (also called Rowe) family led the way to a permanent Methodist church in Box. This was followed in June 1825 when the property of Mr James Rawlings was certificated at Box and in 1828 a dwelling house at Wadswick belonging to Peter Doorey.[17]

The integration of dissenters into social life was imperative as their numbers were so high amongst the weavers and quarrymen of North Wiltshire (possibly between 10% and 30% of the population) and there were numerous establishments registered in Box.[18] The peak period for the certification of houses was around the year 1700, falling off in the 1760s, then picking up again after 1800.[19] In April 1702 the dwellinghouse Elizabeth Rogers in Box was registered as a Quaker house certified by Elizabeth, Thomas Beaven and Sarah Young.[20] In August 1802 A certain building belonging to Jacob Ford was registered at Middlehill by James Tanner, John Smith and John Tanner.[21]

The certificated dwelling-houses were often forerunners to the building of designated chapels. In April 1820 a dwelling house in Box (possibly the cottage Woodstock, Mill Lane) belonging to Samuel Roe, described as Wesleyan Methodist, was registered by Daniel Campbell, minister of Bradford-on-Avon and Rev Mr Smith, Hog Lane.[22] Further registrations followed: in 1825 a building owned by Mr James Rawlings, Independent, certified by Henry Wibley, dissenting minister of Corsham; in 1827 a house owned by Peter Doorey, Independent, of Wadswick, certified by Peter, Henry Aust, James Day, Thomas Shell, Moses Mizen, Nathaniel Webb and Joseph Doorey.[23] The breakthrough in establishing a permanent church was made on 3 March 1834 when Catherine Rowe and Thomas Noble of Box registered A chapel in our possession and the story of the Methodist Chapel in the centre of Box is given elsewhere on the website.[24]

We can discover more about these families and the role of women in establishing the Methodist movement. Born at Freshford, Somerset, in 1786, three years before the French Revolution, Catherine Rowe was a formidable woman of absolute religious certainty. Freshford was visited several times by John Wesley and a Methodist Chapel was built there in 1783. After the death of her husband, Catherine lived in Box and worked as a baker. In 1841 she was living at The Barracks in Box (possibly the Poorhouse) with a score of other people including her daughter, Elizabeth, and son-in-law Thomas Noble, who was a tea-dealer. Half a century later when Lady Dickson-Poynder opened the present chapel in 1897, Mrs Fuller of Neston Park spoke and

Miss Noble presided at the harmonium.[25] After so many years of conflict, the dissenting movement was accepted in Box.

If there was enough interest, nonconformist meetings were organised in the private dwelling houses of supporters. In 1802

a house belonging to Jacob Ford was certificated at Middlehill.[16] The Roe (also called Rowe) family led the way to a permanent Methodist church in Box. This was followed in June 1825 when the property of Mr James Rawlings was certificated at Box and in 1828 a dwelling house at Wadswick belonging to Peter Doorey.[17]

The integration of dissenters into social life was imperative as their numbers were so high amongst the weavers and quarrymen of North Wiltshire (possibly between 10% and 30% of the population) and there were numerous establishments registered in Box.[18] The peak period for the certification of houses was around the year 1700, falling off in the 1760s, then picking up again after 1800.[19] In April 1702 the dwellinghouse Elizabeth Rogers in Box was registered as a Quaker house certified by Elizabeth, Thomas Beaven and Sarah Young.[20] In August 1802 A certain building belonging to Jacob Ford was registered at Middlehill by James Tanner, John Smith and John Tanner.[21]

The certificated dwelling-houses were often forerunners to the building of designated chapels. In April 1820 a dwelling house in Box (possibly the cottage Woodstock, Mill Lane) belonging to Samuel Roe, described as Wesleyan Methodist, was registered by Daniel Campbell, minister of Bradford-on-Avon and Rev Mr Smith, Hog Lane.[22] Further registrations followed: in 1825 a building owned by Mr James Rawlings, Independent, certified by Henry Wibley, dissenting minister of Corsham; in 1827 a house owned by Peter Doorey, Independent, of Wadswick, certified by Peter, Henry Aust, James Day, Thomas Shell, Moses Mizen, Nathaniel Webb and Joseph Doorey.[23] The breakthrough in establishing a permanent church was made on 3 March 1834 when Catherine Rowe and Thomas Noble of Box registered A chapel in our possession and the story of the Methodist Chapel in the centre of Box is given elsewhere on the website.[24]

We can discover more about these families and the role of women in establishing the Methodist movement. Born at Freshford, Somerset, in 1786, three years before the French Revolution, Catherine Rowe was a formidable woman of absolute religious certainty. Freshford was visited several times by John Wesley and a Methodist Chapel was built there in 1783. After the death of her husband, Catherine lived in Box and worked as a baker. In 1841 she was living at The Barracks in Box (possibly the Poorhouse) with a score of other people including her daughter, Elizabeth, and son-in-law Thomas Noble, who was a tea-dealer. Half a century later when Lady Dickson-Poynder opened the present chapel in 1897, Mrs Fuller of Neston Park spoke and

Miss Noble presided at the harmonium.[25] After so many years of conflict, the dissenting movement was accepted in Box.

Roman Catholicism

After a long period of peaceful relations between the Catholic and Protestant strands of religion, many might have thought that all was well. The issues with Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot was a century earlier in 1605, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 firmly ensured a Protestant royal succession, and the Test Acts of 1673 and 1678 prohibited Catholics from public employment. Many felt it was time to relax the restraints on Catholic worship and a Toleration Act was introduced in Quebec in 1774 and four years later an act was introduced to allow them to own property in Britain.

It came as a shock when Protestant Associations started to assemble large crowds protesting against Popery (Catholicism) under the direction of Lord George Gordon in 1779. A mob of 60,000 people destroyed property in London and attacked Newgate Prison in 1780, inspiring copycat riots nation-wide. On 9 June 1780 a mob in Bath destroyed a Roman Catholic chapel near St James' Parade, which had only been built in 1777 and still had not been officially opened. The crowd sacked the house of the priest, Father Dr John Bede Brewer, who crossed the River Avon to escape.[26] Rioting continued until 4am when the crowd was dispersed by troops. A footman from the Royal Crescent, John Butler, was executed for his part in inciting the Bath crowd with a penny whistle, one of the last public hangings in the city.[27] It is hard to believe that the Georgian period was indifferent to religious matters.

After a long period of peaceful relations between the Catholic and Protestant strands of religion, many might have thought that all was well. The issues with Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot was a century earlier in 1605, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 firmly ensured a Protestant royal succession, and the Test Acts of 1673 and 1678 prohibited Catholics from public employment. Many felt it was time to relax the restraints on Catholic worship and a Toleration Act was introduced in Quebec in 1774 and four years later an act was introduced to allow them to own property in Britain.

It came as a shock when Protestant Associations started to assemble large crowds protesting against Popery (Catholicism) under the direction of Lord George Gordon in 1779. A mob of 60,000 people destroyed property in London and attacked Newgate Prison in 1780, inspiring copycat riots nation-wide. On 9 June 1780 a mob in Bath destroyed a Roman Catholic chapel near St James' Parade, which had only been built in 1777 and still had not been officially opened. The crowd sacked the house of the priest, Father Dr John Bede Brewer, who crossed the River Avon to escape.[26] Rioting continued until 4am when the crowd was dispersed by troops. A footman from the Royal Crescent, John Butler, was executed for his part in inciting the Bath crowd with a penny whistle, one of the last public hangings in the city.[27] It is hard to believe that the Georgian period was indifferent to religious matters.

Box Methodist

Family Trees

Catherine Rowe (1789-1855)

Children: Elizabeth (b 1811) who married Thomas Noble (b 1804 at Batcombe, Somerset, d 1867)

Catherine was the sister of Samuel Rowe (1786-1831)

Children of Elizabeth and Thomas Noble:

Samuel Rowe Noble (1833-1904), in his youth a coal merchant, and later stone merchant, who married Elizabeth Pictor (b 1834), fourth daughter of Job Pictor) in 1864.[28] In 1871 they lived at Steam Mills, in 1881 and 1891 at Manor Farm (where he was described as farmer of 44 acres and stone merchant, in 1901 at Frogmore House and on his death before 1904 at Lorne Villa.

Elizabeth Noble worked as a baker (like her mother Catherine Rowe) between 1851 and 1871, employing the same families, the Cullen and Smith families, to work in the bakery and as domestic servants. There is a popular story of Robert Pictor permitting one of the galleries in Spring Quarry to be used for miners' meetings. This quarry is still known as Chapel Ground.[29]

Children of Samuel Rowe Noble and Elizabeth (nee Pictor)

Mildred Mary (b 1867); Estell R (b 1870); Frederick Thomas (b 1871)

Family Trees

Catherine Rowe (1789-1855)

Children: Elizabeth (b 1811) who married Thomas Noble (b 1804 at Batcombe, Somerset, d 1867)

Catherine was the sister of Samuel Rowe (1786-1831)

Children of Elizabeth and Thomas Noble:

Samuel Rowe Noble (1833-1904), in his youth a coal merchant, and later stone merchant, who married Elizabeth Pictor (b 1834), fourth daughter of Job Pictor) in 1864.[28] In 1871 they lived at Steam Mills, in 1881 and 1891 at Manor Farm (where he was described as farmer of 44 acres and stone merchant, in 1901 at Frogmore House and on his death before 1904 at Lorne Villa.

Elizabeth Noble worked as a baker (like her mother Catherine Rowe) between 1851 and 1871, employing the same families, the Cullen and Smith families, to work in the bakery and as domestic servants. There is a popular story of Robert Pictor permitting one of the galleries in Spring Quarry to be used for miners' meetings. This quarry is still known as Chapel Ground.[29]

Children of Samuel Rowe Noble and Elizabeth (nee Pictor)

Mildred Mary (b 1867); Estell R (b 1870); Frederick Thomas (b 1871)

References

[1] Penelope J Corfield, Secularisation or Otherwise in Eighteenth Century England, British History in the Long Eighteenth Century, podcast

[2] EJ Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Captain Swing, 1969, Penguin Books, p34

[3] David Ibberson, The Vicars of Thomas a Becket, Box, 1987, Appendix 1

[4] David Ibberson, The Vicars of Thomas a Becket, Box, 1987, p.24

[5] Wiltshire Record Society, vol 21, p.40 and John Ayers, B-Ed Course, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre Ref 2265, p.22

[6] Steve Hobbs, Wiltshire Glebe Terriers 1588-1827, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol.56, p.43

[7] See article on Box Tithes

[8] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Volume III, p.114

[9] Gwynne Stock, The 18th and early 19th Century Quaker Burial Ground at Bathford, Bath and North-East Somerset, published in Grave Concerns - Death and Burial in England 1700 - 1850, York Council for British Archaeology, Research Report 113

[10] Commander AS Craig, The Quakers and Bathford, Bathford Local History Society p.30-41

[11] John Wesley's Journal is available on-line at https://www.ccel.org/ccel/wesley/journal.html

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 8 September 1904

[13] John Wesley's Journal, p.63

[14] This section is indebted to Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton Publishers, p.111

[15] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, p.112

[16] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, 1985, Wiltshire Record Society Vol 40, p.58

[17] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.108 and 116

[18] Keith Wrightson, Early Modern England Politics, Religion and Society, Podcast, Chapter 22

[19] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, 1985, Wiltshire Record Society Vol 40, p.xxix

[20] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.11

[21] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.58

[22] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.90

[23] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.108 and 116

[24] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.135

[25] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 11 February 1897

[26] The Bath Chronicle, 27 November 1915 and Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 2 November 1935

[27] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 27 April 1935

[28] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 20 October 1864

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Volume IV, p.249

[1] Penelope J Corfield, Secularisation or Otherwise in Eighteenth Century England, British History in the Long Eighteenth Century, podcast

[2] EJ Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Captain Swing, 1969, Penguin Books, p34

[3] David Ibberson, The Vicars of Thomas a Becket, Box, 1987, Appendix 1

[4] David Ibberson, The Vicars of Thomas a Becket, Box, 1987, p.24

[5] Wiltshire Record Society, vol 21, p.40 and John Ayers, B-Ed Course, A Christian & Useful Education, Wiltshire History Centre Ref 2265, p.22

[6] Steve Hobbs, Wiltshire Glebe Terriers 1588-1827, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol.56, p.43

[7] See article on Box Tithes

[8] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Volume III, p.114

[9] Gwynne Stock, The 18th and early 19th Century Quaker Burial Ground at Bathford, Bath and North-East Somerset, published in Grave Concerns - Death and Burial in England 1700 - 1850, York Council for British Archaeology, Research Report 113

[10] Commander AS Craig, The Quakers and Bathford, Bathford Local History Society p.30-41

[11] John Wesley's Journal is available on-line at https://www.ccel.org/ccel/wesley/journal.html

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 8 September 1904

[13] John Wesley's Journal, p.63

[14] This section is indebted to Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, 1993, Alan Sutton Publishers, p.111

[15] Derek Parker and John Chandler, Wiltshire Churches: An Illustrated History, p.112

[16] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, 1985, Wiltshire Record Society Vol 40, p.58

[17] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.108 and 116

[18] Keith Wrightson, Early Modern England Politics, Religion and Society, Podcast, Chapter 22

[19] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, 1985, Wiltshire Record Society Vol 40, p.xxix

[20] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.11

[21] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.58

[22] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.90

[23] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.108 and 116

[24] JH Chandler, Wiltshire Dissenters' Meeting House Certificates and Registrations 1689-1852, p.135

[25] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 11 February 1897

[26] The Bath Chronicle, 27 November 1915 and Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 2 November 1935

[27] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 27 April 1935

[28] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 20 October 1864

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Volume IV, p.249