|

Why Do We Speak English? Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse June 2020 It has been estimated that 1.5 billion people speak English worldwide, not all as their first language. This equates to 20% of the world's population, compared to 500 million who speak Spanish, the second largest language at 7%. The reasons for this are complex - British imperialism, American economic dominance, English literature and, increasingly, the need for a lingua franca in scientific and academic work. It is outside the scope of this article to consider how English became so dominant out of hundreds of Indo-European languages, 445 of which still exist in the world. Not least of the difficulties is that the language was unwritten for centuries after its adoption in England, making it more unclear why a very small, isolated Indo-European language should have developed here in the first place. This article seeks to explore the early Saxon origins of the language which we now call "Old English" . This was the language which developed into modern English. The words are difficult for modern people to read but the spoken words are much easier to understand, clearly the fore-runner of our current communication. |

Germanic Immigration

There have been various estimates of the number of immigrants into England in the century or so after AD 350 with numbers varying from 20,000 to 200,000.[1] No generally accepted number has emerged and figures seem extremely speculative. However, most historians and archaeologists believe that the invasion numbers were very small compared to a Romano-British population of England which has been calculated between 1.5 and 4 million people, perhaps 2.5 million.[2] In other words, the incomers were probably between 1 and 10 percent of the entire existing population. The question therefore arises: why do we all speak English, the language of only a small minority of people?

The language replaced by Old English wasn’t classical Latin - that was the speech used in Roman towns, administration and the Church.[3] Bede listed the languages spoken in early 700s as Old English, British Celtic, Irish, Pictish, classical Church Latin, and vernacular spoken Latin. Local people had their own Brittonic language and probably their own local dialect, now lost, although there are a few British words that are believed to have survived: broc meaning a badger, crag a rock, and tor hill.[4]

There have been various estimates of the number of immigrants into England in the century or so after AD 350 with numbers varying from 20,000 to 200,000.[1] No generally accepted number has emerged and figures seem extremely speculative. However, most historians and archaeologists believe that the invasion numbers were very small compared to a Romano-British population of England which has been calculated between 1.5 and 4 million people, perhaps 2.5 million.[2] In other words, the incomers were probably between 1 and 10 percent of the entire existing population. The question therefore arises: why do we all speak English, the language of only a small minority of people?

The language replaced by Old English wasn’t classical Latin - that was the speech used in Roman towns, administration and the Church.[3] Bede listed the languages spoken in early 700s as Old English, British Celtic, Irish, Pictish, classical Church Latin, and vernacular spoken Latin. Local people had their own Brittonic language and probably their own local dialect, now lost, although there are a few British words that are believed to have survived: broc meaning a badger, crag a rock, and tor hill.[4]

Place-name Evidence

Although the number of British place-names has been seen to be more common than previously suggested, most of the basic words in our language are West Saxon.[5] These include words like mann (man), wĭf (wife), cild (child), hūs (house),

weall (wall), mete (meat), gõd (good) and strang (strong).

Box appears to have both British and Saxon place-names. Surviving British place-names include combe used in the name Alcombe and Wyre as in Wyres Lane (possibly a British river name).[6] Cumbre (meaning British, compare Cymru) is recalled at Cumberwell (near Kingsdown) and John Chandler’s research into Francis Allen’s 1626 maps revealed that a well named CVM WELL, CVMA WELL and CUMBAr WELL is marked between Chapel Plaister and Hatt on various versions of the maps.[7]

A few Saxon place-names can be recorded. An early name for the By Brook was Weavern Brook, used from 957 until the mid-1600s. The name possibly derived from the Saxon word for winding and survives as Weavern Farm and Weavern Meadow.[8] Another local name may be Worm. One historian has claimed that the burial mounds throughout England came to be feared as the homes of dragons or serpents (worms) although they were sometimes re-used as funerary monuments. This gives rise to speculation about the Saxon compound word Worm-cliff and Worm-wood Farm in Box.[9]

Although the number of British place-names has been seen to be more common than previously suggested, most of the basic words in our language are West Saxon.[5] These include words like mann (man), wĭf (wife), cild (child), hūs (house),

weall (wall), mete (meat), gõd (good) and strang (strong).

Box appears to have both British and Saxon place-names. Surviving British place-names include combe used in the name Alcombe and Wyre as in Wyres Lane (possibly a British river name).[6] Cumbre (meaning British, compare Cymru) is recalled at Cumberwell (near Kingsdown) and John Chandler’s research into Francis Allen’s 1626 maps revealed that a well named CVM WELL, CVMA WELL and CUMBAr WELL is marked between Chapel Plaister and Hatt on various versions of the maps.[7]

A few Saxon place-names can be recorded. An early name for the By Brook was Weavern Brook, used from 957 until the mid-1600s. The name possibly derived from the Saxon word for winding and survives as Weavern Farm and Weavern Meadow.[8] Another local name may be Worm. One historian has claimed that the burial mounds throughout England came to be feared as the homes of dragons or serpents (worms) although they were sometimes re-used as funerary monuments. This gives rise to speculation about the Saxon compound word Worm-cliff and Worm-wood Farm in Box.[9]

English Language

Old English is different to other Indo-European languages. It is the richest of all Germanic languages, using alliterative, compound words to express new ideas. It is the earliest recorded Germanic language and, in its time, was the second most important European language after Latin.

Old English is different to other Indo-European languages. It is the richest of all Germanic languages, using alliterative, compound words to express new ideas. It is the earliest recorded Germanic language and, in its time, was the second most important European language after Latin.

|

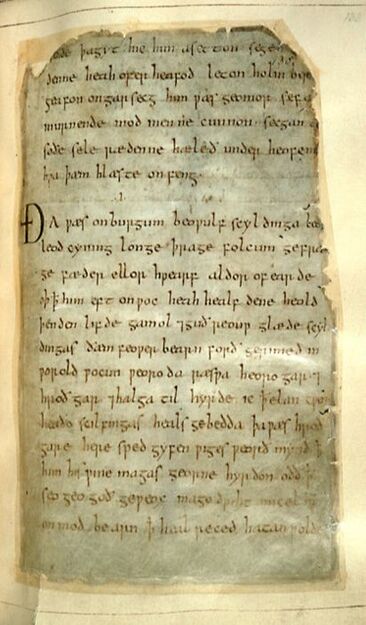

There are 1,500 charters defining the boundaries of Saxon land-holdings but the outstanding feature of Old English is the 30,000 lines of poetry which have survived, much of it of religious interpretation such as The Dream of the Rood. They were copied on vellum by monks in Latin and Old English in about the year 1000 and recorded to preserve the information in both the language of the people and of the church.[10] Almost all the lines are contained in only a handful of collections: the Caedmon manuscript, the Exeter Book, the Vercelli Book, and the Nowell Codex.[11]

|

Modern Translation of Dream of the Rood Listen, I will tell the best of visions, what came to me in the middle of the night, when voice-bearers dwelled in rest, It seemed to me I saw a wondrous tree lifted in the air, wound round with light, the brightest of beams. |

The Exeter Book wasn’t always preserved carefully, being used at various times as a chopping block, and a resting place for a beer mug and a poker. Many of the lines are riddles which are often quite rude. An example is: What hangs down by the thigh of a man, under his cloak, yet is stiff and hard? When the man pulls up his robe, he puts the head of this hanging thing into that familiar hole of matching length which he has filled many times before. Answer – A key. Some of the poems are religious or elegiac and only five can be described as heroic. All of them were originally intended for oral recitation by minstrels in a period of general illiteracy.

Because Old English declined it could not be rhymed because it had different endings to denote grammatical function (such as subject and object, possessive and dative cases). A different structure was used to assist the poet’s memory often based on dividing each line into two parts. There were various line structures, sometimes with two alliterative words in the first part and one in the second.

Because Old English declined it could not be rhymed because it had different endings to denote grammatical function (such as subject and object, possessive and dative cases). A different structure was used to assist the poet’s memory often based on dividing each line into two parts. There were various line structures, sometimes with two alliterative words in the first part and one in the second.

|

Beowulf

The most famous Anglo-Saxon poem is Beowulf.[12] The poem was written in Old English and recorded for posterity by monks several centuries later. Its opening lines about the tribe of Danes called the Spear-Danes has often been quoted: Lo! the Spear-Danes' glory through splendid achievements The folk-kings' former fame we have heard of, How princes displayed then their prowess-in-battle. |

The poem Beowulf survives in a single manuscript of about AD 1000 although the date of the original authorship is uncertain. It tells the story of a Scandinavian Viking and its depictions of life and heroic adventures are assumed to mirror those of Saxon society. |

Saxons were once a maritime people just like the Vikings and Beowulf tells the story of a heroic Danish lord possibly around the year 750, a tribe called the Geats, and their struggle against the inhabitants of South Sweden. It is claimed to express the nature of Saxon virtues: heroic, battle-hardened struggles and the defeat of enemies: Sorrow not ... Better it is for every man that he avenge his friend than that he mourn greatly. Each of us must abide the end of this world's life; let him who may, work mighty deeds 'ere he die, for afterwards, when he lies lifeless, that is best for a warrior.

The poem is rooted in Germanic folklore, with Beowulf’s fights against mythical monsters which he killed by tearing off their limbs, his own mortal wounding by a fire-breathing dragon, and plenty of feasting and drinking. It is based on moral themes of loyalty to family, treachery, and friendship generated in the mead hall. These were the traditions of Germano-Scandinavian people of the time and have been recalled in the works of JRR Tolkien, Seamus Heaney and others.

The poem is rooted in Germanic folklore, with Beowulf’s fights against mythical monsters which he killed by tearing off their limbs, his own mortal wounding by a fire-breathing dragon, and plenty of feasting and drinking. It is based on moral themes of loyalty to family, treachery, and friendship generated in the mead hall. These were the traditions of Germano-Scandinavian people of the time and have been recalled in the works of JRR Tolkien, Seamus Heaney and others.

|

West Saxon Views of Romano-British Culture

In a magnificent Saxon poem referred to as The Ruin we can see how much the Saxons admired their ancestors, calling their buildings enta geweorc (the work of the Giants). The poem probably dates from about 700 and is generally believed to be about Bath. It depicts the wonder that subsequent generations had for the civilisation of their Roman predecessors. It wasn’t recorded contemporaneously but written down by monks about the year 1000 and only fragments survive. This marvellous translation tries to replicate the rhyme and rhythms of Saxon poetry.[13] |

|

The Ruin

Wondrous is this wall-stead, wasted by fate. Battlements broken, giant’s work shattered. Roofs are in ruin, towers destroyed, Broken the barred gate, rime on the plaster, walls gape, torn up, destroyed, consumed by age. Earth-grip holds the proud builders, departed, long lost, and the hard grasp of the grave, until a hundred generations of people have passed. Often this wall outlasted, hoary with lichen, red-stained, withstanding the storm, one reign after another; the high arch has now fallen. The wall-stone still stands, hacked by weapons, by grim-ground files. Mood quickened mind, and the mason, skilled in round-building, bound the wall-base, wondrously with iron. Bright were the halls, many the baths, High the gables, great the joyful noise, many the mead-hall full of pleasures. Until fate the mighty overturned it all. |

Slaughter spread wide, pestilence arose, and death took all those brave men away. Their bulwarks were broken, their halls laid waste, the cities crumbled, those who would repair it laid in the earth. And so these halls are empty, and the curved arch sheds its tiles, torn from the roof. Decay has brought it down, broken it to rubble. Where once many a warrior, high of heart, gold-bright, gleaming in splendour, proud and wine-flushed, shone in armour, looked on a treasure of silver, on precious gems, on riches of pearl... in that bright city of broad rule. Stone courts once stood there, and hot streams gushed forth, wide floods of water, surrounded by a wall, in its bright bosom, there where the baths were, hot in the middle. Hot streams ran over hoary stone into the ring (Parts of the original manuscript are missing) |

Language Imposition or Adoption?

The Germanic immigrants spoke different languages to the existing population and, as we have seen, did not arrive in numbers large enough to be able to impose the use of their language. Nor is it plausible that immigrants rapidly assumed political leadership, forcing locals to adopt their language to achieve recognition from the new aristocracy. In all likelihood existing people spoke two or more languages, switching between them according to the context in which they found themselves. Certainly, Bede seems to assume some degree of multilingualism, and the survival of Latin elements amongst English place-names, as well as the influence Brittonic seems to have had on Old English syntax, supports this assertion.

Some theories have suggested that it was the adaptability and expressiveness of English that made it the most convenient and popular language. This interpretation better reflects the higher ambitions of the poem Beowulf and the feeling of awe expressed in The Ruin. But this cannot be the only reason for its adoption because the composition of this poetry post-dates the period during which the language was adopted. Old English must have gained currency quickly. By the mid-500s the Byzantine historian Procopius describes the inhabitants of Britain as Angli, Brittones and Frisiones. By the end of that century Pope Gregory was aware of the Angli, and by about AD 600 Æthelberht of Kent uses Old English to write a law code, suggesting that it was in vernacular use during the 500s.

Conclusion

So, why do we speak English? The truth is opaque and we can only theorise. Perhaps the polyglot population began to favour one particular mode of speech for everyday transactions, much as some people today consciously adopt particular modes of speech to emphasise their social identity. In such a manner may English have become the lingua franca, but we do not have a truly satisfactory explanation yet.

The Germanic immigrants spoke different languages to the existing population and, as we have seen, did not arrive in numbers large enough to be able to impose the use of their language. Nor is it plausible that immigrants rapidly assumed political leadership, forcing locals to adopt their language to achieve recognition from the new aristocracy. In all likelihood existing people spoke two or more languages, switching between them according to the context in which they found themselves. Certainly, Bede seems to assume some degree of multilingualism, and the survival of Latin elements amongst English place-names, as well as the influence Brittonic seems to have had on Old English syntax, supports this assertion.

Some theories have suggested that it was the adaptability and expressiveness of English that made it the most convenient and popular language. This interpretation better reflects the higher ambitions of the poem Beowulf and the feeling of awe expressed in The Ruin. But this cannot be the only reason for its adoption because the composition of this poetry post-dates the period during which the language was adopted. Old English must have gained currency quickly. By the mid-500s the Byzantine historian Procopius describes the inhabitants of Britain as Angli, Brittones and Frisiones. By the end of that century Pope Gregory was aware of the Angli, and by about AD 600 Æthelberht of Kent uses Old English to write a law code, suggesting that it was in vernacular use during the 500s.

Conclusion

So, why do we speak English? The truth is opaque and we can only theorise. Perhaps the polyglot population began to favour one particular mode of speech for everyday transactions, much as some people today consciously adopt particular modes of speech to emphasise their social identity. In such a manner may English have become the lingua franca, but we do not have a truly satisfactory explanation yet.

References

[1] Not just the Angles, Saxons and Jutes noted by Bede; it becomes increasingly evident that the immigrants were drawn from a wider area of Europe and the Mediterranean

[2] Francis Pryor, The Making of the British Landscape, 2010, Penguin Books, p.167 and Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.37

[3] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 29

[4] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 30

[5] Simon Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006. Archaeopress, p.89-90

[6] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol 1 Part 2, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.482

[7] John Chandler, Cumberwell in Box, The Recorder: Annual newsletter of the Wiltshire Record Society 11, February 2012

[8] JEB.Gover, Allen Mawer, and FM.Stenton, The Placenames of Wiltshire, 1939, Cambridge University Press, p.4 and 82

[9] Sarah Semple, quoted in Thomas JT Williams, Landscape and warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/emed.12107/full, 30 June 2015

[10] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 38

[11] 90% of all surviving lines of poetry are preserved in just 7 manuscripts

[12] The date and origin of Beowulf have been fiercely contested. There seems to be an emerging, but by no means universal, consensus that it was composed some time between 685-750, probably in Mercia

[13] Siân Echard, University of British Columbia http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/sechard/oeruin.htm

[1] Not just the Angles, Saxons and Jutes noted by Bede; it becomes increasingly evident that the immigrants were drawn from a wider area of Europe and the Mediterranean

[2] Francis Pryor, The Making of the British Landscape, 2010, Penguin Books, p.167 and Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.37

[3] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 29

[4] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 30

[5] Simon Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006. Archaeopress, p.89-90

[6] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol 1 Part 2, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.482

[7] John Chandler, Cumberwell in Box, The Recorder: Annual newsletter of the Wiltshire Record Society 11, February 2012

[8] JEB.Gover, Allen Mawer, and FM.Stenton, The Placenames of Wiltshire, 1939, Cambridge University Press, p.4 and 82

[9] Sarah Semple, quoted in Thomas JT Williams, Landscape and warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/emed.12107/full, 30 June 2015

[10] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 38

[11] 90% of all surviving lines of poetry are preserved in just 7 manuscripts

[12] The date and origin of Beowulf have been fiercely contested. There seems to be an emerging, but by no means universal, consensus that it was composed some time between 685-750, probably in Mercia

[13] Siân Echard, University of British Columbia http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/sechard/oeruin.htm