Why Railways Came to Box Alan Payne May 2017

Importance of the Rail Transport

Contemporaries realised the significance of the project as early as 1834, describing it as remarkable .. believed to be unprecedented.[1] The London and Bristol line was the talk of the age throughout the nation; at that time no other railway line in the world existed at a length of over 100 miles.[2] Above all it was railways' speed and reliability that was utterly novel; where previously the fastest mail coaches could average 9 miles per hour and passenger coaches 7 mph, the railway promised 20 mph and the chance of going places and returning the same day.

Contemporaries realised the significance of the project as early as 1834, describing it as remarkable .. believed to be unprecedented.[1] The London and Bristol line was the talk of the age throughout the nation; at that time no other railway line in the world existed at a length of over 100 miles.[2] Above all it was railways' speed and reliability that was utterly novel; where previously the fastest mail coaches could average 9 miles per hour and passenger coaches 7 mph, the railway promised 20 mph and the chance of going places and returning the same day.

|

From the outset the London and Bristol line was conceived as a passenger carrying service. The name Great Western Railway was selected in preference to London and Bristol Railway to promote the international aspect of the route which accessed America through the ships The Great Western and Great Britain.[3]

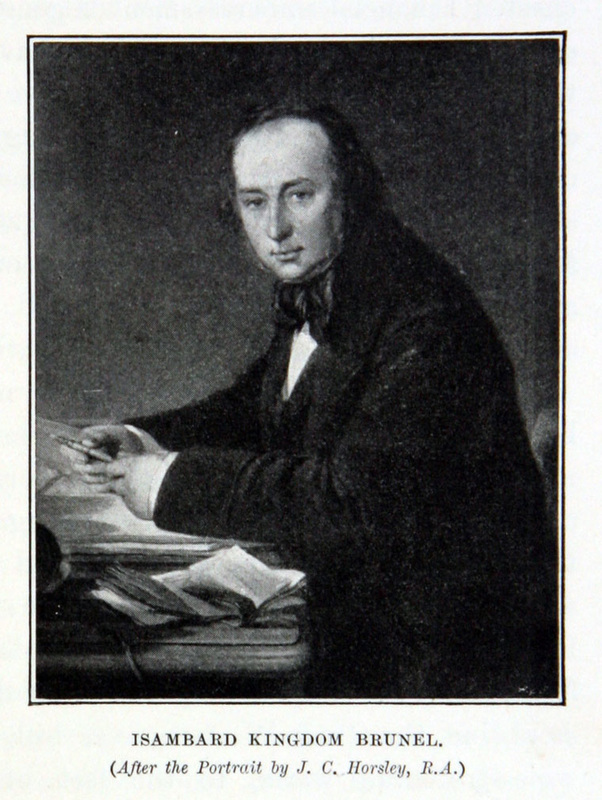

The advantage for Bath was for families coming there for pleasure or as invalids; Bath was already an acknowledged place of favourite resort ... The Railway would enable them to reach this from London in four hours and a half, and without any fatigue.[4] Not all were in favour, though, and in January 1839 a memorial was presented to the directors in Bristol urging the duty of the suppression of Sunday travelling on their lines from the consideration of the immense moral evil .[5] The Bishop of Bath and Wells and his fellows continued the opposition in 1841, being the guardians of the spiritual welfare and moral character of the people of the kingdom, were alarmed at the prospect of the running of railway trains upon the Lord's Day.[6] Right: Brunel painted by John Callcott Horsley in 1857 (courtesy National Portrait Gallery) |

Route Through Box

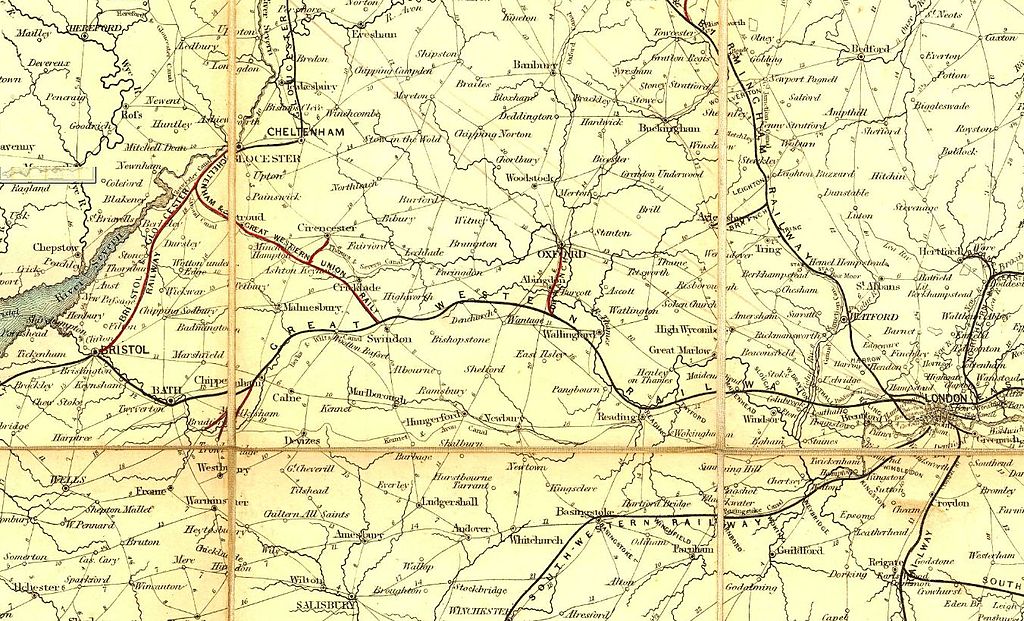

The argument in favour of a railway line through Box was by no means a forgone conclusion. The road engineer Macadam suggested a route through Marshfield and Wootton Bassett avoiding Box.[7] There were many who favoured a southern line going through Basing, Trowbridge and Bradford-on-Avon to Bath and completely ignoring Box. A noisy and contentious public meeting was held in Bath in September 1834 chaired by Sir Thomas Fellowes who advocated the southern route picking up manufacturing needs in those towns and giving better accessibility to Melksham and Westbury.[8]

Eventually Mr Brunel himself was called upon to give his opinion. He argued unequivocally in favour of a northern line, through the North Wiltshire Vale, going through Box. The underlying reasons for the choice of that line became obvious at a later date to access the Oxford, Cheltenham and Gloucester populations and to connect with the rapidly expanding north of England by joining with the London and Birmingham Railway.[9] By the 1860s God's Wonderful Railway had a monopoly over the western route through to Wales, down to the south-west and up to the West Midlands.

The argument in favour of a railway line through Box was by no means a forgone conclusion. The road engineer Macadam suggested a route through Marshfield and Wootton Bassett avoiding Box.[7] There were many who favoured a southern line going through Basing, Trowbridge and Bradford-on-Avon to Bath and completely ignoring Box. A noisy and contentious public meeting was held in Bath in September 1834 chaired by Sir Thomas Fellowes who advocated the southern route picking up manufacturing needs in those towns and giving better accessibility to Melksham and Westbury.[8]

Eventually Mr Brunel himself was called upon to give his opinion. He argued unequivocally in favour of a northern line, through the North Wiltshire Vale, going through Box. The underlying reasons for the choice of that line became obvious at a later date to access the Oxford, Cheltenham and Gloucester populations and to connect with the rapidly expanding north of England by joining with the London and Birmingham Railway.[9] By the 1860s God's Wonderful Railway had a monopoly over the western route through to Wales, down to the south-west and up to the West Midlands.

|

It is interesting that, in the initial share prospectus, the local lawyers for the Great Western Railway were solicitors in Bath. They were two people who had significant Box connections Messrs Mant and Bruce.[10]

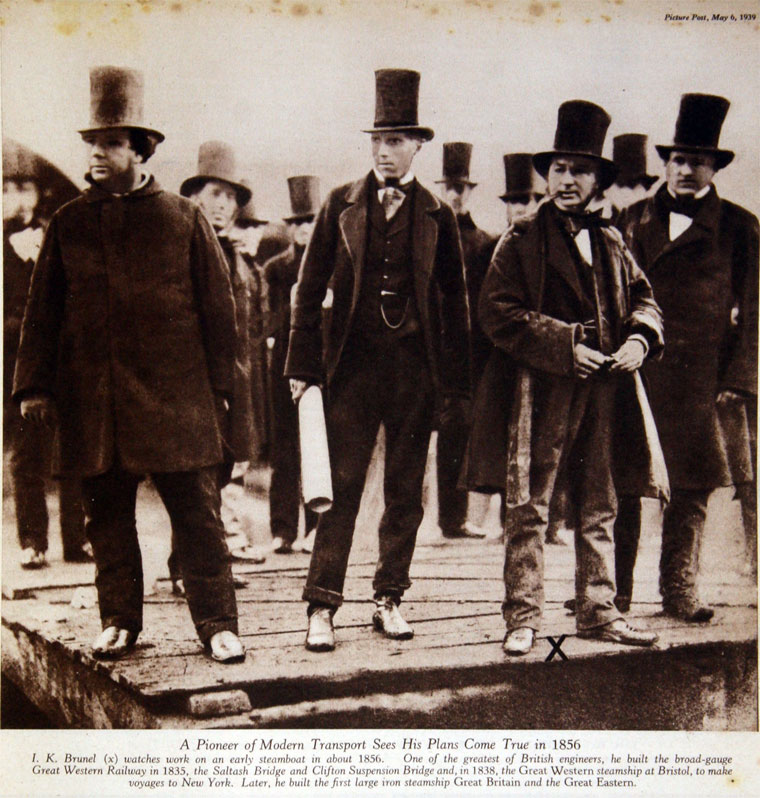

The Mant family lived in Middlehill and their story was recorded in the contemporary diary of Martha Shaw. The Bruce family later took up residence in the village at Ashley House, near Shockerwick. There is anecdotal evidence that the owners of Shockerwick House refused to have the railway on their land, which limited the route of the line to the present.[11] The precise route chosen was more nearly level than any other Railway yet projected, but would be costly especially in the hilly country about Bath and Bristol.[12] The route was christened Mr Brunel's billiard table.[13] Left: Brunel second right at the launch of the Great Eastern in 1858, a year before his death (courtesy Wikipedia) |

Acquiring the Land

After approval by parliament the railway companies had compulsory purchasing rights to acquire properties on the route to build the permanent way, destroying in its course more than 500 dwelling houses, besides a corresponding number of workshops, gardens and other valuable property.[14]

After approval by parliament the railway companies had compulsory purchasing rights to acquire properties on the route to build the permanent way, destroying in its course more than 500 dwelling houses, besides a corresponding number of workshops, gardens and other valuable property.[14]

|

In the year 1840-41 it was a case of out with the medieval world, represented by the abolition of the church tithe system in 1840, and in with the industrial age brought by the railway itself. In the tithe apportionment details there are references to William Brewer who owned land and a beer shop in the Rudloe area.

|

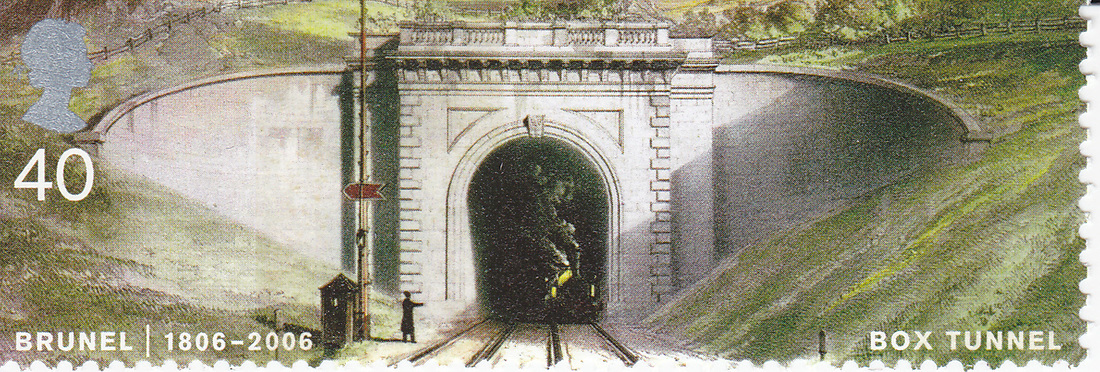

Mr Bewer was the contractor who had been tunnelling through Box Hill since 1836 to excavate Box Tunnel. The Great Western Railway Company was one of the largest payers of tithe in the area with 41 acres, 3 roods and 37 perches in 1840, land they owned for the railway, at Ashley for Box Station, and at Shockerwick for the railway crossing. It was all a last minute addition for the surveyors who drew the route of the line and the tunnels in pencil on their existing 1840 maps (above courtesy Wilts History Centre) until it could be included properly by the Ordnance Survey of 1885 (below, courtesy of Wilts History Centre).

Why a Station at Box?

Even more eventful was the decision to build the station at Box. The resolve to stop here was taken late in the GWR's planning process and it was only in October 1840 that the directors made a formal decision.[15] The directors' minutes recorded that the principal passenger stations were to be at Swindon, Wootton Bassett and Chippenham and it was decided that minor stations be also fixed at Corsham near Pound Pill and the village of Box at the foot of the inclined plain.

This is a fascinating reference because the inclined plain refers to the need for a banker engine to push trains through the Box Tunnel. It is clear that the decision to construct a station was not for goods or passengers trade but rather the station was built close to the point where the banker engine was coupled to trains and the station was needed to provide logistical support of staff, points and maintenance for employing the banker engine.

It was a momentous decision because the station allowed building stone to be easily loaded onto the national railway and turned Box from a rural location into a manufacturing centre based on the quarry industry.

Even more eventful was the decision to build the station at Box. The resolve to stop here was taken late in the GWR's planning process and it was only in October 1840 that the directors made a formal decision.[15] The directors' minutes recorded that the principal passenger stations were to be at Swindon, Wootton Bassett and Chippenham and it was decided that minor stations be also fixed at Corsham near Pound Pill and the village of Box at the foot of the inclined plain.

This is a fascinating reference because the inclined plain refers to the need for a banker engine to push trains through the Box Tunnel. It is clear that the decision to construct a station was not for goods or passengers trade but rather the station was built close to the point where the banker engine was coupled to trains and the station was needed to provide logistical support of staff, points and maintenance for employing the banker engine.

It was a momentous decision because the station allowed building stone to be easily loaded onto the national railway and turned Box from a rural location into a manufacturing centre based on the quarry industry.

References

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 27 March 1834

[2] George Henry Gibbs, Extracts of the Diary and Correspondence, edited Jack Simmons, 1971, Adams & Dart, p.3

[3] Geoffrey Channon, Birth of GWR, 1985, Historical Association, p.7

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 9 January 1834 meeting in Bath

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 31 January 1839

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 7 October 1841

[7] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.280

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 18 September 1834

[9] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 2002, Hambledon and London, p.66

[10] The Bath Chronicle, 9 January 1834 share prospectus

[11] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 11 October 1930

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 9 January 1834 share prospectus

[13] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, p.79

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 27 March 1834

[15] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.135

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 27 March 1834

[2] George Henry Gibbs, Extracts of the Diary and Correspondence, edited Jack Simmons, 1971, Adams & Dart, p.3

[3] Geoffrey Channon, Birth of GWR, 1985, Historical Association, p.7

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 9 January 1834 meeting in Bath

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 31 January 1839

[6] The Bath Chronicle, 7 October 1841

[7] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.280

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 18 September 1834

[9] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 2002, Hambledon and London, p.66

[10] The Bath Chronicle, 9 January 1834 share prospectus

[11] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 11 October 1930

[12] The Bath Chronicle, 9 January 1834 share prospectus

[13] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, p.79

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 27 March 1834

[15] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.135