Wessex Under Attack Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse, December 2020

|

The early 800s seemed to have resolved the conflict between West Saxon and Mercian forces. Under the ealdorman Wechstan, the Wiltshiremen defended the area against Mercian attack at Kempsford in 802 and launched their own attack on Mercia after the death of Cenwulf of Mercia in 821. The West Saxons conquered Mercia and took over the lordship of the whole of southern England.[1] It was a short-lived peace, however.

Just as the Saxon-Mercian conflict seemed to be resolved, a new and more aggressive force started to pose a much larger challenge = the incursion and later settlement of various Scandinavian forces that have collectively been called the Vikings. Alfred_king_of_Wessex_London_880_By PHGCOM - Own work by uploader, photographed at the British Museum, Public Domain, httpscommons.wikimedia.orgwindex.phpcurid=5969131 |

|

The Vikings

The Scandinavian seafarers we call Vikings came from the North Sea area of Norway, Denmark and Sweden. Some settled in Ireland and Normandy, France, and launched further local attacks. Traditionally the first major Viking attack was in the northeast, when Lindisfarne was sacked in 793 . Then, in the 830s and 840s, there were sporadic Danish Viking attacks on the south coast of England from Normandy and later attacks on the west of England via the Bristol Channel from Norwegian Vikings settled in Ireland and the west coast of Scotland. These were generally repelled until the Great Heathen Army after 865, which ravaged down to Wessex in 870 during the reign of Æthelred I, Alfred’s father. |

King Alfred (Ruled 871-899)

Alfred acceded to the throne of the West Saxons in 871 after the deaths of his three older brothers. At first, he addressed the threat of Viking encroachment by paying a ransom in 877 but it didn’t resolve matters. The Viking Guthrum assumed control of a large Scandinavian force in southern England and defeated Alfred’s Saxon army at Chippenham on the Christian feast day of Epithany on 6th January 878. The Wiltshire ealdorman Wulfhere submitted the county to him at Chippenham, although Somerset and Devon remained free.[2] Alfred’s flight into the Somerset Levels and the apocryphal story of the burning of cakes encouraged the Saxons to repel the invaders after the Battle of Edington, near Westbury. The cake story is believed to be invented because it only appears in later English sources in the late 900s, and apparently was lifted from Scandinavian literature, where a similar tale is told in respect of a Scandinavian leader. Both the words cake and burn have Viking derivations.[3]

Alfred’s defence of Wessex greatly extended the burdens on ordinary people to finance and support protection against Viking attack. He enforced military service, road- and bridge-building and the creation of burhs (fortified towns), enforced by a system of punishment including land forfeiture. In his Book of Laws, Alfred established a system of judicial centres for shires and elementary hundreds (originally meaning 100 hides - in Wiltshire about 5,000 acres of arable land) and tithings (one tenth of a hundred, in other words 10 hides).[4]

These times were a period of enhanced centralised control. Shire courts met four times a year under the authority of an ealdorman or bishop and their purpose was to organise and allocate royal demands for financial and military duty. Hundred courts met more regularly every four weeks, often under the control of the royal reeve, to enforce local law and maintain civil order.[5] The court system was developed by Alfred’s successors and were regularised in the Hundred Ordinance written in the decades around 950. More local levels of control also existed and the tithing areas seem to have had a role in collecting food rents. Every freeman over 12 years of age was allocated to a tithing area and swore an oath to keep the king’s peace and assist in capturing criminals.[6] Wiltshire had a shire court at Wilton with local administration devolved to 40 hundred moots (meeting places) in Wiltshire, including Malmesbury (Colepark), Braford-on-Avon (Bradford Leigh) and Warminster (Iley Oak).[7] It is possible that three separate Saxon hundreds existed in Chippenham (later merged) with Box possibly a tithing in the hundred of Cepeham, Chippenham. Although we know nothing about Box from the records, it is worth mentioning that a tithing (10 hides) originally supported 10 Saxon households and that Box was later recorded as half that size, which might indicate the density of population in Box at this time.

Alfred acceded to the throne of the West Saxons in 871 after the deaths of his three older brothers. At first, he addressed the threat of Viking encroachment by paying a ransom in 877 but it didn’t resolve matters. The Viking Guthrum assumed control of a large Scandinavian force in southern England and defeated Alfred’s Saxon army at Chippenham on the Christian feast day of Epithany on 6th January 878. The Wiltshire ealdorman Wulfhere submitted the county to him at Chippenham, although Somerset and Devon remained free.[2] Alfred’s flight into the Somerset Levels and the apocryphal story of the burning of cakes encouraged the Saxons to repel the invaders after the Battle of Edington, near Westbury. The cake story is believed to be invented because it only appears in later English sources in the late 900s, and apparently was lifted from Scandinavian literature, where a similar tale is told in respect of a Scandinavian leader. Both the words cake and burn have Viking derivations.[3]

Alfred’s defence of Wessex greatly extended the burdens on ordinary people to finance and support protection against Viking attack. He enforced military service, road- and bridge-building and the creation of burhs (fortified towns), enforced by a system of punishment including land forfeiture. In his Book of Laws, Alfred established a system of judicial centres for shires and elementary hundreds (originally meaning 100 hides - in Wiltshire about 5,000 acres of arable land) and tithings (one tenth of a hundred, in other words 10 hides).[4]

These times were a period of enhanced centralised control. Shire courts met four times a year under the authority of an ealdorman or bishop and their purpose was to organise and allocate royal demands for financial and military duty. Hundred courts met more regularly every four weeks, often under the control of the royal reeve, to enforce local law and maintain civil order.[5] The court system was developed by Alfred’s successors and were regularised in the Hundred Ordinance written in the decades around 950. More local levels of control also existed and the tithing areas seem to have had a role in collecting food rents. Every freeman over 12 years of age was allocated to a tithing area and swore an oath to keep the king’s peace and assist in capturing criminals.[6] Wiltshire had a shire court at Wilton with local administration devolved to 40 hundred moots (meeting places) in Wiltshire, including Malmesbury (Colepark), Braford-on-Avon (Bradford Leigh) and Warminster (Iley Oak).[7] It is possible that three separate Saxon hundreds existed in Chippenham (later merged) with Box possibly a tithing in the hundred of Cepeham, Chippenham. Although we know nothing about Box from the records, it is worth mentioning that a tithing (10 hides) originally supported 10 Saxon households and that Box was later recorded as half that size, which might indicate the density of population in Box at this time.

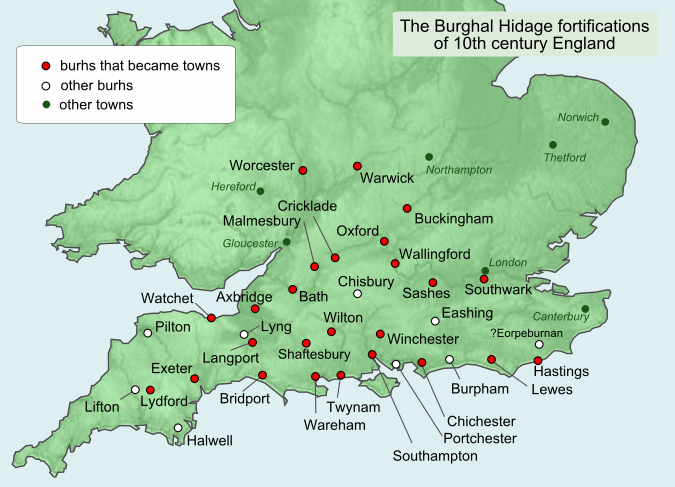

Burghal Hidage

A surviving record called the Burghal Hidage (a list of fortified towns, mainly in Wessex) appears to date from Alfred’s time or shortly thereafter. It records the lengths of fortifications needed to protect burhs (fortified towns) including Bath 4,125 feet of defences, Malmesbury 4,950 and Cricklade 6,187.[8] To pay for the work, burghal areas were assessed for tax as a certain number of hides. Wiltshire was assessed as 4,800 hides, including Wilton 1,400 hides, Cricklade 1,500, Malmesbury 1,200 and Tisbury 500.[9] Somerset was valued as 2,613 hides including Bath 1,000 hides.[10] Royal manors were not included as they were not taxed and there is no direct evidence to our area.

This taxation imposed a considerable financial burden on all local people to build and man the defences. It has been estimated that one man had to serve in the army for every 5 hides (possibly the size of the Box area), each member of the army either on active service (including defence of a sector of the burh defences) or at home farming to supply provisions.[11] There is a curious reference to Danegeld in Box in a post-Conquest document which superficially refers to local Vikings. About 1135 Humphrey de Bohun and Bartholomew Bigod granted a mill in Box to Farleigh Priory: free and quit of everything as free alms (without tax), except the scutage (commutation tax) of a knight and so much Danegeld as is due from the mill.[12] At first glance this appears to refer to Viking involvement in Box but probably not as up to the mid-1100s the term was used by the Anglo-Normans to describe recurrent taxes due to the king and doesn’t imply Scandinavian settlement.

A surviving record called the Burghal Hidage (a list of fortified towns, mainly in Wessex) appears to date from Alfred’s time or shortly thereafter. It records the lengths of fortifications needed to protect burhs (fortified towns) including Bath 4,125 feet of defences, Malmesbury 4,950 and Cricklade 6,187.[8] To pay for the work, burghal areas were assessed for tax as a certain number of hides. Wiltshire was assessed as 4,800 hides, including Wilton 1,400 hides, Cricklade 1,500, Malmesbury 1,200 and Tisbury 500.[9] Somerset was valued as 2,613 hides including Bath 1,000 hides.[10] Royal manors were not included as they were not taxed and there is no direct evidence to our area.

This taxation imposed a considerable financial burden on all local people to build and man the defences. It has been estimated that one man had to serve in the army for every 5 hides (possibly the size of the Box area), each member of the army either on active service (including defence of a sector of the burh defences) or at home farming to supply provisions.[11] There is a curious reference to Danegeld in Box in a post-Conquest document which superficially refers to local Vikings. About 1135 Humphrey de Bohun and Bartholomew Bigod granted a mill in Box to Farleigh Priory: free and quit of everything as free alms (without tax), except the scutage (commutation tax) of a knight and so much Danegeld as is due from the mill.[12] At first glance this appears to refer to Viking involvement in Box but probably not as up to the mid-1100s the term was used by the Anglo-Normans to describe recurrent taxes due to the king and doesn’t imply Scandinavian settlement.

|

Church Reorganisation

Personal religious zeal was clearly part of Alfred’s philosophy and he and his successors used the church as part of his call for loyalty by depicting the Vikings as heathen invaders. There was also considerable reorganisation of ecclesiastic structures. The minster church system had been struggling to cope because parochial areas were too large for central monastic brethren to deliver weekly mass to all people so local churches were built in the smaller tithing areas, overseen either by the minster church or some by appointment from lay sponsors. Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder, divided the Wessex sees into five bishoprics: Winchester, Sherborne, Ramsbury, Wells and Abingdon.[13] To reward allies for services rendered, kings often granted churches to lay supporters and lands to churches to support their parish priest. Alfred’s father, Aethelwulf, surrendered a tenth of his lands to the church before he abdicated in 858 and left to go on pilgrimage to Rome. |

We get no information about the response of ordinary people to these ecclesiastic changes. Alfred, his successors and lay patrons brought devotional imagery to people by starting to install relics in important churches and minsters to encourage regular observance. Malmesbury acquired fragments of Christ’s cross and part of the crown of thorns.[14]

The tithe system in England has uncertain origins but was clearly a considerable financial burden obliging people to pay one-tenth of the annual harvest to the minster church.[15] The right to receive tithes may have been better locally enforced when it was granted to the English churches by King Aethelwulf in 855. By 960 we have written charters from King Edgar which detail the situation at the close of this period. He defined the action to be taken if tithes were not paid: the king’s reeve is to go there, and the bishop’s reeve and the mass-priest of the minster, and they are to seize without his consent the tenth part for the minster to which it belongs.[16]

The tithe system in England has uncertain origins but was clearly a considerable financial burden obliging people to pay one-tenth of the annual harvest to the minster church.[15] The right to receive tithes may have been better locally enforced when it was granted to the English churches by King Aethelwulf in 855. By 960 we have written charters from King Edgar which detail the situation at the close of this period. He defined the action to be taken if tithes were not paid: the king’s reeve is to go there, and the bishop’s reeve and the mass-priest of the minster, and they are to seize without his consent the tenth part for the minster to which it belongs.[16]

|

Assessing Alfred's Reputation

It is difficult to get a balanced view of Alfred’s achievements because his reputation has been absorbed into English mythology. Whilst Alfred was certainly concerned with developing a national identity as a counter to the Viking threat, he called himself King of the Anglo-Saxons rather than King of England because he never ruled the Danelaw area from Mercia to Northumberland. It was his great grandson King Edgar (959-75) who called himself King of the English in his coronation ceremony in 973. Alfred’s time is often said to have introduced an English cultural renaissance with an emphasis in the royal court on education and literacy and he personally translated a number of clerical texts from Latin into Old English.[17] The creation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (written in Old English) is generally believed to date from the 890s, seeking to renew Alfred’s early military success in the face of later Viking attacks and Asser’s Life of Alfred (written in Latin) has been provisionally dated to 893, six years before Alfred’s death.[18] |

Royal House of Wessex 871-899 Alfred King of Anglo-Saxons 899-924 Edward the Elder, son of Alfred 924 Ælfweard, son of Edward the Elder 924-939 Æthelstan, son of Edward the Elder 939-946 Edmund I 946-955 Eadred 955-959 Eadwig 959-975 Edgar the Peaceful 975-978 Edward the Martyr 978-1013 Æthelred II the Unready 1013-14 Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark 1014-16 Æthelred II the Unready restored 1016 Edmund Ironside |

The use of the title Great to describe Alfred probably derived from the imagination of the writers of Romances and chivalry in the later middle ages. By the end of Alfred’s reign, the threat of Danish attack had clearly not been extinguished and Viking incursion continued to be a major problem for his successors. Alfred’s fame would have been different if his successors had fallen to the Vikings and if we had become a permanent part of a Scandinavian Empire.

Political Instability under Alfred’s Successors

Alfred’s victories didn’t resolve the problem of Viking attacks and increasing numbers of Scandinavian people settled in England. The Vikings built up a massive Scandinavian empire trading in the late 700s from Byzantium, India, the Mediterranean and even the first Europeans in North America.[19] For over two centuries, they were primarily traders exchanging silks, spices and other exotic goods. Their raids on England and other countries extracted gold, silver and slaves which they used to barter for other goods. Of course, the Vikings got a very bad press from the monastic chroniclers – most weren’t Christian and regarded oaths sworn to two sticks in the shape of a cross, in the same way we would regard two sticks in a different shape.

Political Instability under Alfred’s Successors

Alfred’s victories didn’t resolve the problem of Viking attacks and increasing numbers of Scandinavian people settled in England. The Vikings built up a massive Scandinavian empire trading in the late 700s from Byzantium, India, the Mediterranean and even the first Europeans in North America.[19] For over two centuries, they were primarily traders exchanging silks, spices and other exotic goods. Their raids on England and other countries extracted gold, silver and slaves which they used to barter for other goods. Of course, the Vikings got a very bad press from the monastic chroniclers – most weren’t Christian and regarded oaths sworn to two sticks in the shape of a cross, in the same way we would regard two sticks in a different shape.

|

On Alfred’s death, his eldest son Edward (known as Edward the Elder) ruled Wessex from 899 to 924 although his succession was fiercely challenged at first by his cousin Æthelwold, who sought Viking military help from Danelaw areas of east and north-east England. Viking armies were active at Cricklade in 903 and a Viking force sailed up the Severn Estuary, landing at Watchet and Porlock and attacking Somerset in 914.[20] Edward conquered Danelaw areas in East Anglia and the East Midlands often with the help of his sister, Æthelflæd(the Lady of the Mercians) who had married the Mercian king. The military strategy in the early 900s seems to have been to buy off Viking incursions with huge amounts of gold. Royal officials took over responsibility for defence and failure to pay geld demands could result in the confiscation of landowners’ property, especially that which had been gifted as bocland or book land (land where ownership was vested by charter, and thus alienable, as opposed to inalienable folcland).[21]

Edward the Elder was succeeded briefly by his second son Ælfweard in 924, then by his first son Æthelstan from 924 to 939. It was the latter who pronounced himself the first King of England. He took over Mercia and he has been claimed as one of the great Anglo-Saxon kings, annexing Viking-controlled Northumberland, becoming bretwalda (overlord) of south Scotland and Wales, and running a royal court to emulate Charlemagne. After his victory at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, Æthelstan called himself Rex Britanniae (King of Britain) but he never married and had no legitimate heirs throwing the succession into doubt. |

Minority Rulers

For forty years after the death of Æthelstan in 939, there was a succession of short-term, underage rulers, the first two of whom were Æthelstan’s half-brothers: Edmund I (939-946) who was stabbed to death at Pucklechurch, Gloucestershire, and then Eadred (946-955), who died unmarried without heir. The kingdom was then divided between Edmund I’s sons, the unpopular Eadwig aged 15 years (955-959) and the so-called Edgar the Peaceful aged 16 (959-975). The authority of Edgar the Peaceful was clearly in need of propping up and, late in his reign in 973, he was crowned in Bath by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The ceremony has become something of an institution and is still replicated by the coronation of British monarchs. Civil war broke out on Edgar the Peaceful’s death in 975 and his son Æthelred II, aged 12, eventually succeeded his brother Edward the Martyr aged 13 (975-978), murdered at Corfe Castle. Most of these rulers were local – Edmund I was buried at Glastonbury Abbey, Eadred died at Frome, Edgar the Peaceful was buried in Glastonbury Abbey.

It isn't known who was running the country during these changes of ruler. There has been much discussion about the use made of the witenagemot (witan), once believed to have been a formal organisation of advisers. This has now been largely discounted in favour of an occasional assembly of invited advisers in ad-hoc moots (meetings).

For forty years after the death of Æthelstan in 939, there was a succession of short-term, underage rulers, the first two of whom were Æthelstan’s half-brothers: Edmund I (939-946) who was stabbed to death at Pucklechurch, Gloucestershire, and then Eadred (946-955), who died unmarried without heir. The kingdom was then divided between Edmund I’s sons, the unpopular Eadwig aged 15 years (955-959) and the so-called Edgar the Peaceful aged 16 (959-975). The authority of Edgar the Peaceful was clearly in need of propping up and, late in his reign in 973, he was crowned in Bath by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. The ceremony has become something of an institution and is still replicated by the coronation of British monarchs. Civil war broke out on Edgar the Peaceful’s death in 975 and his son Æthelred II, aged 12, eventually succeeded his brother Edward the Martyr aged 13 (975-978), murdered at Corfe Castle. Most of these rulers were local – Edmund I was buried at Glastonbury Abbey, Eadred died at Frome, Edgar the Peaceful was buried in Glastonbury Abbey.

It isn't known who was running the country during these changes of ruler. There has been much discussion about the use made of the witenagemot (witan), once believed to have been a formal organisation of advisers. This has now been largely discounted in favour of an occasional assembly of invited advisers in ad-hoc moots (meetings).

The reign of Edgar the Peaceful saw a major effort to counter Viking sea attacks. During the 10th century (possibly in Edgar’s rule) the hundreds were reorganised into groups of three to fund ship-building with a levy called shipsoke.[22] Legal and administrative reforms included the enforcement of a single system of laws throughout his kingdom and standardisation of coinage. He enforced central royal authority through the aristocracy and the church and, with his adviser Dunstan, rebuilt several monasteries, enforced celibacy amongst priests and forbidding simony (selling church positions). Landowners enforced control of the shire and hundred courts and it is believed that the numerous grants of land at this time were an attempt to secure loyalty from an increasingly powerful elite.[23]

Impact on Box in 900s

There is no information about how these changing political events affected life in the Box area. We can see that the Vikings had a considerable impact partly from the large number of Danish words that have been integrated into everyday English language – words like sister, sky, dirt, eggs, leg, bag, give, take and call.[24] They have given many synonyms for our lexicon which over time these have taken slightly different connotations. For example, the following words are Old Norse (followed by their Anglo-Saxon equivalents): skill (craft), skin (hide), anger (ire), ill (sick).[25] Interestingly, the word Fogleigh is a compound of Old Norse (fog) and Saxon (leah). Slaughter as in nearby Slaughterford is also a Viking word.

Impact on Box in 900s

There is no information about how these changing political events affected life in the Box area. We can see that the Vikings had a considerable impact partly from the large number of Danish words that have been integrated into everyday English language – words like sister, sky, dirt, eggs, leg, bag, give, take and call.[24] They have given many synonyms for our lexicon which over time these have taken slightly different connotations. For example, the following words are Old Norse (followed by their Anglo-Saxon equivalents): skill (craft), skin (hide), anger (ire), ill (sick).[25] Interestingly, the word Fogleigh is a compound of Old Norse (fog) and Saxon (leah). Slaughter as in nearby Slaughterford is also a Viking word.

References

[1] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.5

[2] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.111

[3] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 47

[4] It is difficult to precisely date the origin of these courts. Hundred courts are first mentioned 945-961 (Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.124)

[5] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.124

[6] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.130

[7] Quoted in The History of Wiltshire, Wikipedia, but not referenced

[8] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.115

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.15, although recent evidence suggests this is overstated by 700 hides of Chisbury, Dorset, see DH Hill, The Burghal Hidage: the establishment of a text,1969, Medieval Archaeology 13, 84-92)

[10] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.89-90 and 117

[11] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.121

[12] Frank M Stenton, The First Century of English Feudalism, 1932, Oxford University Press, p.185 and Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box, Wiltshire: Our Medieval Lords, 2016, ELSP, p.100

[13] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.210 and Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.26-8

[14] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.209

[15] Michael Aston & Carenza Lewis, The Medieval Landscape of Wessex, 1995, Oxbow Monographs, p.62

[16] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, 1989, JM Dent & Sons, p.128-9

[17] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.200

[18] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.104-5

[19] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/03/31/how-vikings-made-the-new-world-their-own/

[20] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.132

[21] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.130

[22] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.129

[23] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.103-4

[24] Albert C Baugh and Thomas Cable, A History of the English Language, 1993, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.98

[25] Albert C Baugh and Thomas Cable, A History of the English Language, 1993, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.99

[1] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.5

[2] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.111

[3] Kevin Stroud, The History of English podcast, chapter 47

[4] It is difficult to precisely date the origin of these courts. Hundred courts are first mentioned 945-961 (Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.124)

[5] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.124

[6] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.130

[7] Quoted in The History of Wiltshire, Wikipedia, but not referenced

[8] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.115

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.15, although recent evidence suggests this is overstated by 700 hides of Chisbury, Dorset, see DH Hill, The Burghal Hidage: the establishment of a text,1969, Medieval Archaeology 13, 84-92)

[10] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.89-90 and 117

[11] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.121

[12] Frank M Stenton, The First Century of English Feudalism, 1932, Oxford University Press, p.185 and Jane Cox, The Norman Conquest of Box, Wiltshire: Our Medieval Lords, 2016, ELSP, p.100

[13] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.210 and Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.26-8

[14] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.209

[15] Michael Aston & Carenza Lewis, The Medieval Landscape of Wessex, 1995, Oxbow Monographs, p.62

[16] Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape, 1989, JM Dent & Sons, p.128-9

[17] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.200

[18] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.104-5

[19] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/03/31/how-vikings-made-the-new-world-their-own/

[20] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.132

[21] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.130

[22] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.129

[23] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.103-4

[24] Albert C Baugh and Thomas Cable, A History of the English Language, 1993, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.98

[25] Albert C Baugh and Thomas Cable, A History of the English Language, 1993, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p.99