|

War Looming

Alan Payne September 2022 Throughout the inter-war years, most of the residents of Box were hoping that war could be avoided. There was a similar sentiment throughout the country. The threat of international instability might have been apparent to some people by 1928 when 41 different parties stood in the German Federal elections. But the desire for peace continued. In March 1934 the Box vicar talking about: “These days are critical for .. international peace” and in November that year the Archbishop of Canterbury spoke of “The price of peace”. |

League of Nations

The peace achieved by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 inspired by US President Woodrow Wilson established a League of Nations (later called United Nations) at Geneva, Switzerland, which proposed to outlaw war and protect the rights of small nations. The Conservative Member of Parliament, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil (later Lord Cecil), a barrister and Chancellor of Birmingham University, spent his life advocating the role of the League of Nations in promoting peace. But his work was recognised too late and he was only awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1937.

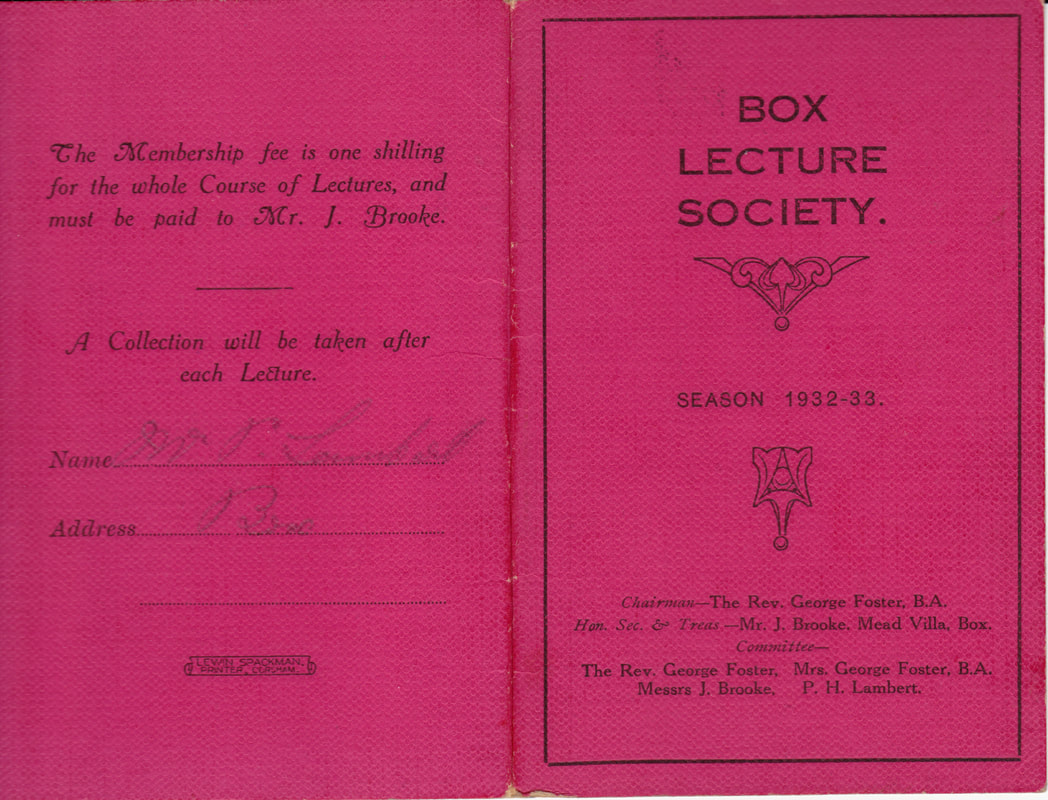

The vicar of Box Rev George Foster spoke passionately about the need for peace in 1928 when the German economy was booming in a way to challenge Britain. In the parish magazine he wrote: The desire for peace is widespread; what is needed is to translate that emotion and wish into a real will to pursue peace and to treat war as a barbarous custom unworthy of civilised men.[1] The League of Nations is recognised increasingly as something really worthy of support by all men and women of good will. He called upon villagers to start a local branch of the League as a way of resolving differences of opinion. He used the piece to criticise the House of Commons for rejecting changes to the Book of Common Prayer and called on the value of arbitration as a more Christian and more sensible method of adjudicating differences. Most of the sentiments (however well intentioned) were wiped away by the stock market crash of October 1929 and the rise of Nazism.

The situation deteriorated quickly when Hitler became the German Chancellor in 1933, with the execution of political enemies and the police forces coming under the direct control of Heinrich Himmler. In 1934 vicar Rev George Foster recorded: These days are very critical .. for international peace .. Harder work for peace and not for weak-kneed trembling is what should be one of the signs which man may see in us who profess to follow Christ who is the Prince of Peace.[2]

The peace achieved by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 inspired by US President Woodrow Wilson established a League of Nations (later called United Nations) at Geneva, Switzerland, which proposed to outlaw war and protect the rights of small nations. The Conservative Member of Parliament, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil (later Lord Cecil), a barrister and Chancellor of Birmingham University, spent his life advocating the role of the League of Nations in promoting peace. But his work was recognised too late and he was only awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1937.

The vicar of Box Rev George Foster spoke passionately about the need for peace in 1928 when the German economy was booming in a way to challenge Britain. In the parish magazine he wrote: The desire for peace is widespread; what is needed is to translate that emotion and wish into a real will to pursue peace and to treat war as a barbarous custom unworthy of civilised men.[1] The League of Nations is recognised increasingly as something really worthy of support by all men and women of good will. He called upon villagers to start a local branch of the League as a way of resolving differences of opinion. He used the piece to criticise the House of Commons for rejecting changes to the Book of Common Prayer and called on the value of arbitration as a more Christian and more sensible method of adjudicating differences. Most of the sentiments (however well intentioned) were wiped away by the stock market crash of October 1929 and the rise of Nazism.

The situation deteriorated quickly when Hitler became the German Chancellor in 1933, with the execution of political enemies and the police forces coming under the direct control of Heinrich Himmler. In 1934 vicar Rev George Foster recorded: These days are very critical .. for international peace .. Harder work for peace and not for weak-kneed trembling is what should be one of the signs which man may see in us who profess to follow Christ who is the Prince of Peace.[2]

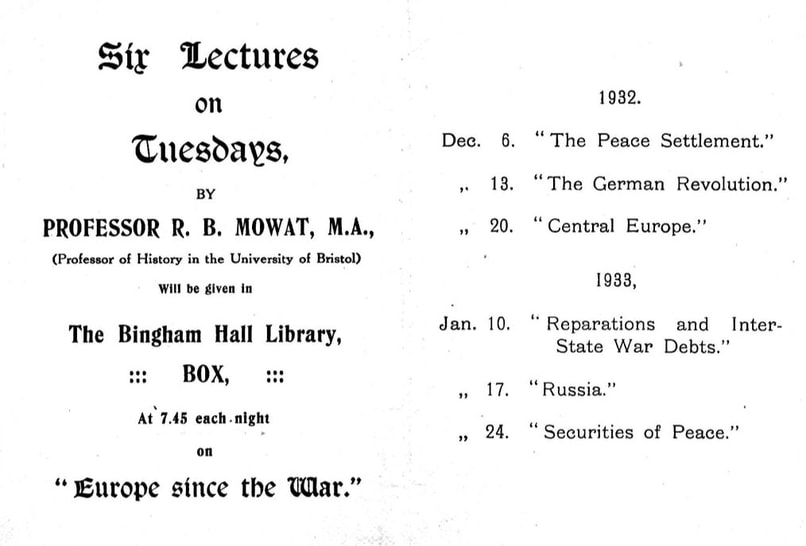

In March 1934 the Box Branch of the League of Nations Union had put on several lectures (magnificent speeches) by Professor RB Mowat of Bristol University, Mr BA Fletcher and Lady Harris.[3] The talks were mostly to bring political events in Germany to public notice and the vicar urged villagers to join the League of Nations to support peace. By November 1934 Hitler had taken full control of Germany as President and Fuhrer and the Archbishop of Canterbury sent an open letter entitled The Price of Peace, stressing the importance of the League of Nations.

To show the commitment of people to the League’s work in favour of peace, a national declaration was proposed in November 1934. Philip Lambert set out five questions including the banning of arms sales and the defence of smaller countries by economic or by military measures. A meeting was held in the Bingham Hall to discuss the proposition Peace or War? but unfortunately there was no record of the final ballot.[4]

War Approaches

Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister from 1937 until May 1940, has been dealt with rather harshly by history, his politics seen as inadequate compared to the more bellicose approach of Winston Churchill. This may be rather unfair, however, because the prevailing desire of people in England before 1939 was in favour of avoiding war. This was true in Box.

By the end of 1935, the parish magazine began to chart the descent into war on the Home Front. The vicar Arthur Maltin proposed a cupboard for emergency supplies (particularly for invalids) in the church with stocks of Ovaltine, Malted Milk, Calves’ Foot Jelly, Bovril, Oxo cubes, cocoa, Virol (bone marrow for children), cornflour and jellies.[5]

In March 1936 a lecture was held in the Bingham Hall about air raid precautions for the protection of the civil population in the event of gas attacks and different techniques needed for various types of poisonous gases.[6] An appeal was started to fund a car for the District Nurse so that she could attend patients more quickly.[7] As war became more likely, Colonel Harry Erling Sykes went on a training course in London and gave detailed air raid lectures in the Box Schools in January and February 1938 together with first-aid instructions from John King of the Box Ambulance Brigade.[8] The talk covered three types of attack, high explosive shells, incendiary bombs and gas bombs.

By 1936 the War Office started buying unworked quarries in Box and Corsham to convert the space into storage areas, quickly followed by other military needs, such as building aircraft tracking facilities and underground armament factories. The first task was clearance of the underground sites and disposing of unwanted stone. It was a huge manual task and hundreds of Irish labourers came to the area to work, reminiscent of the navvies who built the railways a century earlier.

Without local employment, the population of the village was in decline. Headmaster of Box School, Mr Druett spoke about the decreasing numbers in our school are among the babies (classes) and in some ages class numbers were down to fifteen pupils.[9] The vicar commented that there has not been one wedding in the parish church since August Bank Holiday last year. With residential housebuilding now on hold, local work was low-skilled and the stone masons and sculptors who populated the village were not needed. In July 1938, the school register recorded just 178 children, making it scarcely viable compared to over 300 children in the late Victorian period.[10]

To show the commitment of people to the League’s work in favour of peace, a national declaration was proposed in November 1934. Philip Lambert set out five questions including the banning of arms sales and the defence of smaller countries by economic or by military measures. A meeting was held in the Bingham Hall to discuss the proposition Peace or War? but unfortunately there was no record of the final ballot.[4]

War Approaches

Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister from 1937 until May 1940, has been dealt with rather harshly by history, his politics seen as inadequate compared to the more bellicose approach of Winston Churchill. This may be rather unfair, however, because the prevailing desire of people in England before 1939 was in favour of avoiding war. This was true in Box.

By the end of 1935, the parish magazine began to chart the descent into war on the Home Front. The vicar Arthur Maltin proposed a cupboard for emergency supplies (particularly for invalids) in the church with stocks of Ovaltine, Malted Milk, Calves’ Foot Jelly, Bovril, Oxo cubes, cocoa, Virol (bone marrow for children), cornflour and jellies.[5]

In March 1936 a lecture was held in the Bingham Hall about air raid precautions for the protection of the civil population in the event of gas attacks and different techniques needed for various types of poisonous gases.[6] An appeal was started to fund a car for the District Nurse so that she could attend patients more quickly.[7] As war became more likely, Colonel Harry Erling Sykes went on a training course in London and gave detailed air raid lectures in the Box Schools in January and February 1938 together with first-aid instructions from John King of the Box Ambulance Brigade.[8] The talk covered three types of attack, high explosive shells, incendiary bombs and gas bombs.

By 1936 the War Office started buying unworked quarries in Box and Corsham to convert the space into storage areas, quickly followed by other military needs, such as building aircraft tracking facilities and underground armament factories. The first task was clearance of the underground sites and disposing of unwanted stone. It was a huge manual task and hundreds of Irish labourers came to the area to work, reminiscent of the navvies who built the railways a century earlier.

Without local employment, the population of the village was in decline. Headmaster of Box School, Mr Druett spoke about the decreasing numbers in our school are among the babies (classes) and in some ages class numbers were down to fifteen pupils.[9] The vicar commented that there has not been one wedding in the parish church since August Bank Holiday last year. With residential housebuilding now on hold, local work was low-skilled and the stone masons and sculptors who populated the village were not needed. In July 1938, the school register recorded just 178 children, making it scarcely viable compared to over 300 children in the late Victorian period.[10]

Forging a New Society

The inter-war period brought about a totally new order in Britain. The Local Government Act of 1929 abolished the Poor Law unions and transferred administration for social care to local authorities. The second was the 1931 Statute of Westminster Act, which accepted the right of Dominions to have a self-governing legislature, part of a process of reducing British imperial governance. With the abandonment of the Gold Standard in 1931, the British economy became increasingly protectionist. The Import Duties Act of 1932, introduced a protectionist tariff of 10% on most imported goods from non-Dominion countries, ending nearly a century of Free Trade.[11] The decline of the Liberal Party allowed space for the rise of new-style trade unionism and the political Labour Party, which became a dynamic force in post-war Box Hill where its events and outings offered local people comfort and the chance to experience a wider society than their wartime experiences.

Centralising measures for security in the inter-war period altered the role of national government in the lives of ordinary people. There was a trend towards nationalisation with the establishment of the national grid and the Central Electricity Board in 1926, the national planning of production by the Iron and Steel Federation in 1934, and a quota system for coal production and pricing after 1930.[12] The introduction of state marketing boards for milk and pigs in the mid-1930s was intended to encourage production levels. These trends towards centralised interventions in market forces later increased substantially during the Second World War and after with the Beveridge reforms of health and education. It was a far cry from the free market philosophy of Edwardian Britain.

Situation in Box

Box in 1939 would have been inconceivable to residents in 1913 because so much had changed. The localism of the Great Western Railway as one of 130 railway companies had been superseded by four regional monopolies in 1923. The merger of the Bath Stone firms with the Portland Stone firms in 1911 exemplified the decline of stone extraction in our area and the later goverment purchase of the stone tunnels for military use leading to the immigration of new families and an Irish population still sometimes seen in local surnames. The rise in importance of Box Parish Council in place of the Northey family as lords of the manor was a major break with traditions stretching back centuries. These changes brought new inventiveness and energy to an aging Box population and these newcomers became part of the future who rebuilt the village after the Second World War.

The inter-war period brought about a totally new order in Britain. The Local Government Act of 1929 abolished the Poor Law unions and transferred administration for social care to local authorities. The second was the 1931 Statute of Westminster Act, which accepted the right of Dominions to have a self-governing legislature, part of a process of reducing British imperial governance. With the abandonment of the Gold Standard in 1931, the British economy became increasingly protectionist. The Import Duties Act of 1932, introduced a protectionist tariff of 10% on most imported goods from non-Dominion countries, ending nearly a century of Free Trade.[11] The decline of the Liberal Party allowed space for the rise of new-style trade unionism and the political Labour Party, which became a dynamic force in post-war Box Hill where its events and outings offered local people comfort and the chance to experience a wider society than their wartime experiences.

Centralising measures for security in the inter-war period altered the role of national government in the lives of ordinary people. There was a trend towards nationalisation with the establishment of the national grid and the Central Electricity Board in 1926, the national planning of production by the Iron and Steel Federation in 1934, and a quota system for coal production and pricing after 1930.[12] The introduction of state marketing boards for milk and pigs in the mid-1930s was intended to encourage production levels. These trends towards centralised interventions in market forces later increased substantially during the Second World War and after with the Beveridge reforms of health and education. It was a far cry from the free market philosophy of Edwardian Britain.

Situation in Box

Box in 1939 would have been inconceivable to residents in 1913 because so much had changed. The localism of the Great Western Railway as one of 130 railway companies had been superseded by four regional monopolies in 1923. The merger of the Bath Stone firms with the Portland Stone firms in 1911 exemplified the decline of stone extraction in our area and the later goverment purchase of the stone tunnels for military use leading to the immigration of new families and an Irish population still sometimes seen in local surnames. The rise in importance of Box Parish Council in place of the Northey family as lords of the manor was a major break with traditions stretching back centuries. These changes brought new inventiveness and energy to an aging Box population and these newcomers became part of the future who rebuilt the village after the Second World War.

References

[1] Parish Magazine, February 1928

[2] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[3] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[4] Parish Magazine, November 1934

[5] Parish Magazine, December 1935

[6] Parish Magazine, March 1936

[7] Parish Magazine, June 1938

[8] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 22 January 1938 and The Wiltshire Times, 26 February 1938

[9] Parish Magazine, April 1935

[10] Parish Magazine, July 1938

[11] Shortly thereafter some duties were increased massively to 15% and 33%

[12] EJ Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire, 1969, Penguin Books, p.242

[1] Parish Magazine, February 1928

[2] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[3] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[4] Parish Magazine, November 1934

[5] Parish Magazine, December 1935

[6] Parish Magazine, March 1936

[7] Parish Magazine, June 1938

[8] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 22 January 1938 and The Wiltshire Times, 26 February 1938

[9] Parish Magazine, April 1935

[10] Parish Magazine, July 1938

[11] Shortly thereafter some duties were increased massively to 15% and 33%

[12] EJ Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire, 1969, Penguin Books, p.242