Military Village Sited on Ammunitions Depot Alan Payne November 2017

In March 1938 Germany invaded Austria, then it later annexed part of Czechoslovakia. In September 1938 Chamberlain signed the Munich Peace Agreement. Most people hoped that war could be avoided but preparations for war continued unabated.

Within the space of a few years normal life in Box was converted to military purposes. The area became a central part of the national government plans, starting first with the conversion of the quarries into an ammunition depot, then the conversion of Box's factories to military application and lastly the building of aircraft factories underground.

Central Ammunition Depot

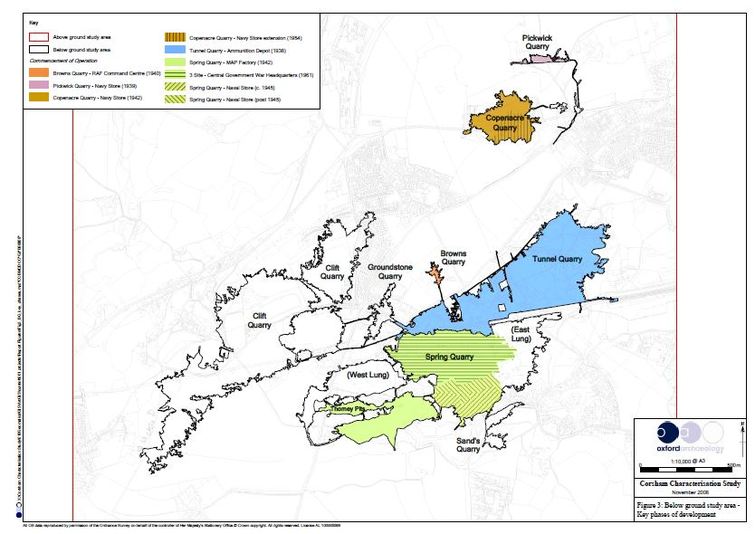

The area was picked out for military usefulness shortly after Hitler came to power in 1933.[1] The authorities were concerned that the Luftwaffe would target London, making stockpiles of bombs at Woolwich Arsenal an easy target.[2] Royal Engineers surveyed sites throughout the United Kingdom including local quarry tunnels for potential use as a munitions and explosives storage facility.[3] The Box and Corsham workings were preferred because they were dry, deep underground, and partly vacant. More than this, there was plenty of skilled undrground workers locally and the Bath and Portland Stone Firms were willing to sell redundant sites.[4]

Within the space of a few years normal life in Box was converted to military purposes. The area became a central part of the national government plans, starting first with the conversion of the quarries into an ammunition depot, then the conversion of Box's factories to military application and lastly the building of aircraft factories underground.

Central Ammunition Depot

The area was picked out for military usefulness shortly after Hitler came to power in 1933.[1] The authorities were concerned that the Luftwaffe would target London, making stockpiles of bombs at Woolwich Arsenal an easy target.[2] Royal Engineers surveyed sites throughout the United Kingdom including local quarry tunnels for potential use as a munitions and explosives storage facility.[3] The Box and Corsham workings were preferred because they were dry, deep underground, and partly vacant. More than this, there was plenty of skilled undrground workers locally and the Bath and Portland Stone Firms were willing to sell redundant sites.[4]

|

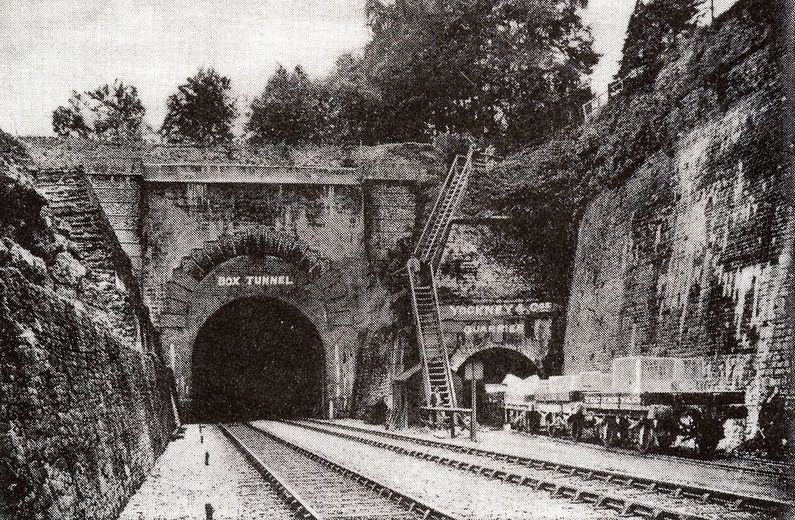

In 1936 the War Office purchased Tunnel Quarry and Ridge Quarry for £35,000 to secure storage areas of 45 and 6 acres respectively. The aim was to create a Central Ammunition Depot, storing three month's ammunition for the British Army Field Force.[5] Ridge Quarry had been in temporary use during the First World War when it was used to store considerable supplies of the explosive TNT (Trinitrotoluene).[6] Tunnel Quarry required extensive repair work: raising the roof height for ammunition wagons, building the depot, installing generators, ventilators, light and heat, kitchens and offices, new roads and gun positions.[7] Access into the storage areas was either via Hudswell Quarry on the north of the railway line or by rail which ran directly off the Box Tunnel.[8]

|

The mines were cleared of two million tons of waste rubble which was deposited on the top of the tunnels as further protection from air bombardment. Local civilian quarrymen were ideal to do the work because of their intimate knowledge of the underground passages and their high safety standards. In addition, some 2,000 colliery workers from Wales, Northumberland and Somerset were also involved.[9] By the end of the war new, level floors were laid, roofs supported with steel girders, ventilation installed, conveyor belts and narrow-guage electric railtracks set up.[10] The amount of work was astounding, reputed to be

11 miles of conveyors, 20 foot thick concrete lining of the Tunnel in places, and heated radiators planned to reduce humidity.[11]

The total cost is said to have been £4.5 million.[12]

11 miles of conveyors, 20 foot thick concrete lining of the Tunnel in places, and heated radiators planned to reduce humidity.[11]

The total cost is said to have been £4.5 million.[12]

The munitions store included bombs, shells and mines removed from Woolwich Arsenal to the bombproof safety of the quarries.[13] The volume of explosive stored was substantial, estimated in total to be 300,000 tons. The underground station at Tunnel Quarry, which had been used for stone-loading, was rebuilt to handle munitions.[14] Much of the activity was at Ridge Quarry which was renamed No 2 Munitions Supply Unit in November 1936. It was ideal because it had a tramway connecting the mine with Corsham Station and winding engines at the mine shaft entrance.[15] In November 1943, The Daily Mail referred to the site as a city: They built a City out of Sight ... an underground City which has taken thousands of men seven years to construct, houses Britain's largest ammunition dump. Details are secret, but it can be said that the stocks are of incredible size.[16]

Other Services departments followed the lead of the War Office. The Air Ministry took over and expanded Ridge Quarry, mostly storing obsolete First World War bombs acquired from USA and materials for the manufacture of bombs in Wales and Hereford.[17] The Admiralty took over Copenacre Quarry for non-explosive storage after Coventry was bombed in 1940.[18]

In the event of a German invasion of London, other parts of the underground quarries were later converted into vaults to store art treasures from the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Portrait Gallery and East European state galleries for countries that had been occupied by the Nazis.[19] The firm De La Rue Ltd leased part of the site to store cash currency, both national and international, for use after the war.[20]

Other Services departments followed the lead of the War Office. The Air Ministry took over and expanded Ridge Quarry, mostly storing obsolete First World War bombs acquired from USA and materials for the manufacture of bombs in Wales and Hereford.[17] The Admiralty took over Copenacre Quarry for non-explosive storage after Coventry was bombed in 1940.[18]

In the event of a German invasion of London, other parts of the underground quarries were later converted into vaults to store art treasures from the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Portrait Gallery and East European state galleries for countries that had been occupied by the Nazis.[19] The firm De La Rue Ltd leased part of the site to store cash currency, both national and international, for use after the war.[20]

|

Militarisation of Residents

The mobilisation of a Civilian Defence Army was well under way by the end of 1938 when postmen delivered National Service Handbooks to Box men and women (nationally to 20 million households).[21] The booklet offered various possibilities for service in a variety of forces: the ARP (Air Raid Precautions), Regular Police, Police Auxiliaries, Regular Fire Brigade, Auxiliary Fire Brigade, Nursing and First Aid, Women's Land Army and, of course, the regular fighting services. The Ministry of Labour thought that about 6 million people were eligible to join up and another 6 million were covered by the Schedule of Reserved Occupations. |

The fear of an imminent war was growing. At Easter time 1939 Box Church had a Three Hours Devotional Service with morning communion at 7am, 8, 9.45 and 12 noon.[22] The choir under the direction of Harry Milsom sang Awake, thou that Sleepest and

Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones. The impending changes seemed to be foretold by the partial eclipse of the sun at 7.20pm on

19 April 1939.[23] Ten thousand gas masks were issued to the Chippenham area in August 1939.[24]

Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones. The impending changes seemed to be foretold by the partial eclipse of the sun at 7.20pm on

19 April 1939.[23] Ten thousand gas masks were issued to the Chippenham area in August 1939.[24]

Les Dancey Recalls the Gas Masks

I am watching the film Dunkirk and it has reminded me about when we had our wartime gas masks issued from a lorry outside the school. My brother Donald, who was five years older than me, was issued with a grown up mask whilst they issued me with a Mickey Mouse type

I was most incensed about this and complained but it didn't get me anywhere. I must have been only three or four years old at the time and never had to wear it anyway. When the German planes were going over we used to hide under the stairs. You are probably aware that the school clock was silenced during the war. It was so good to hear it chiming again after the war.

I am watching the film Dunkirk and it has reminded me about when we had our wartime gas masks issued from a lorry outside the school. My brother Donald, who was five years older than me, was issued with a grown up mask whilst they issued me with a Mickey Mouse type

I was most incensed about this and complained but it didn't get me anywhere. I must have been only three or four years old at the time and never had to wear it anyway. When the German planes were going over we used to hide under the stairs. You are probably aware that the school clock was silenced during the war. It was so good to hear it chiming again after the war.

|

Visible Signs of War

Box was full of military installations by 1939. Pillboxes on the Avon River had been erected and smeared with gas-detecting paint.[25] The access to the railway was protected with a pillbox at Box Tunnel.[26] Anderson shelters (corrugated iron sheets covered with soil), which could offer protection against blast and gas to a family of up to six people, were distributed free to the poorest families. Sandbags and papier-mâché coffins were issued for local storage. Most civilian prisoners were released, the not-too-sick sent home from hospital and many domestic pets were put down. Left: The pillbox still exists in a clump of trees above Box Tunnel (photograph courtesy Richard Bean) |

Many areas in Box became no-go fields where huge stone boulders were set up for military purposes. Kingsdown Common was made inhospitable for landing German aircraft. On the south side of the Roman Road at Hatt, the 100 Acre field was disguised with rocks and boulders to resemble a bombed-out Colerne airfield. It was classified as decoy Q86B, at various times used as a disguise for Colerne, Bath and Box Bridge. The purpose was probably to deceive German bombers into believing they were at an incorrect location and make a false turn on their journeys.[27] The decoy was mainly in use in the period July to November 1942 after German Baedecker Raids on English cities had started in March 1942.

The residents of Box awaited the worst. In June 1939 there was a draft call-up for men aged 20-21 and in August parliament was recalled in the event of war breaking out. The number of people needed to staff the services on the Home Front was insatiable. Later in June 1940 the Bath authorities were advertising for Fifty additional squads, each of three persons, for fire fighting work.[28] The job of these auxiliaries was to keep in check incipient fires which may be caused during an air raid using stirrup pumps until the regular fire service could arrive.

The residents of Box awaited the worst. In June 1939 there was a draft call-up for men aged 20-21 and in August parliament was recalled in the event of war breaking out. The number of people needed to staff the services on the Home Front was insatiable. Later in June 1940 the Bath authorities were advertising for Fifty additional squads, each of three persons, for fire fighting work.[28] The job of these auxiliaries was to keep in check incipient fires which may be caused during an air raid using stirrup pumps until the regular fire service could arrive.

Eric Callaway Recalls Wartime Transport

Jack Bristowe used to run a transport cafe on the A4 before it became the Drop Anchor cafe. It was a wooden shack down quite a long path. Jack used to ask lorry drivers to honk their horn going up Box Hill as a signal to my parents that the cafe needed more eggs, because my parents ran a poultry farm at Dorma on the main road. In return, we received tins of corned beef and other luxury goods which were rationed.

Jack Bristowe used to run a transport cafe on the A4 before it became the Drop Anchor cafe. It was a wooden shack down quite a long path. Jack used to ask lorry drivers to honk their horn going up Box Hill as a signal to my parents that the cafe needed more eggs, because my parents ran a poultry farm at Dorma on the main road. In return, we received tins of corned beef and other luxury goods which were rationed.

Military Transport on Box Roads

From as early as January 1939, the Box roads were preoccupied with moving people and goods around for military purposes.

The Licensing Authority for the Western Area declared that the government work at Box, near Bath, used up all the available transport facilities and they refused an extension of licenses to private hauliers.[29]

The amount of movement in the area caused fatalities on several occasions. In May 1939 an army ambulance collided with a motorcycle ridden by Frederick George Miles of Tisbutts House, Box Hill.[30] Another tragedy occurred in August 1939 when a car taking builders to work at the Devizes Military Camp crashed in heavy mist into a lorry on the A4 near Box Railway Station. The accident killed two men and seriously wounded two others.[31]

From as early as January 1939, the Box roads were preoccupied with moving people and goods around for military purposes.

The Licensing Authority for the Western Area declared that the government work at Box, near Bath, used up all the available transport facilities and they refused an extension of licenses to private hauliers.[29]

The amount of movement in the area caused fatalities on several occasions. In May 1939 an army ambulance collided with a motorcycle ridden by Frederick George Miles of Tisbutts House, Box Hill.[30] Another tragedy occurred in August 1939 when a car taking builders to work at the Devizes Military Camp crashed in heavy mist into a lorry on the A4 near Box Railway Station. The accident killed two men and seriously wounded two others.[31]

Building of Colerne Airfield

Part of the increased traffic on the roads in Box, and more of the activity in the skies, was due to a new airfield at Colerne. Colerne aerodrome was built in the rush to re-arm in the 1930s, one of the final sites to be completed as the Expansion Scheme rapidly tried to make up for the lack of bases in the South-West.[32] Its planning was only finalised in May 1939 to be built immediately on an 800-acre at Cot's Lane which took in parts of three different farms.[33] The completion of its three runways was still being worked on in 1941.

Its purpose was originally as an aircraft Maintenance and Storage Unit but was soon converted to different uses because it was so close to RAF Rudloe Manor, the headquarters of No.10 (Fighter) Group RAF, which was responsible for protecting south-west England, especially Bristol's aircraft factories and Plymouth's naval yards. It was also convenient for the underground aircraft factories which were planned in the tunnels.

In late 1940 No.87 Squadron was based there with the iconic Hawker Hurricane planes, supporting No.11 Group in the Battle of Britain in south-east England and later No.501 Squadron's Spitfire Mark 1s. Numerous other units followed, including No.286 Training Squadron, and training squadrons composed of Canadian, Polish and American pilots. Because of its maintenance capabilities, it often accommodated experimental planes involved in secret special installations including No.616 Squadron, the first permanent Meteor jet fighter squadron in January 1945.[34]

Many military servicemen from Colerne were billeted in Box, more came to visit on days off for relaxation. And even more congestion was added with the amount of traffic from the nearest railway station at Box up to Colerne. In October 1941 the road from the centre of the village up to the airfield at Carters Lane via Inghalls Cottages was made one-way only.[35]

Colerne continued in use after the war, closing in March 1976.

Part of the increased traffic on the roads in Box, and more of the activity in the skies, was due to a new airfield at Colerne. Colerne aerodrome was built in the rush to re-arm in the 1930s, one of the final sites to be completed as the Expansion Scheme rapidly tried to make up for the lack of bases in the South-West.[32] Its planning was only finalised in May 1939 to be built immediately on an 800-acre at Cot's Lane which took in parts of three different farms.[33] The completion of its three runways was still being worked on in 1941.

Its purpose was originally as an aircraft Maintenance and Storage Unit but was soon converted to different uses because it was so close to RAF Rudloe Manor, the headquarters of No.10 (Fighter) Group RAF, which was responsible for protecting south-west England, especially Bristol's aircraft factories and Plymouth's naval yards. It was also convenient for the underground aircraft factories which were planned in the tunnels.

In late 1940 No.87 Squadron was based there with the iconic Hawker Hurricane planes, supporting No.11 Group in the Battle of Britain in south-east England and later No.501 Squadron's Spitfire Mark 1s. Numerous other units followed, including No.286 Training Squadron, and training squadrons composed of Canadian, Polish and American pilots. Because of its maintenance capabilities, it often accommodated experimental planes involved in secret special installations including No.616 Squadron, the first permanent Meteor jet fighter squadron in January 1945.[34]

Many military servicemen from Colerne were billeted in Box, more came to visit on days off for relaxation. And even more congestion was added with the amount of traffic from the nearest railway station at Box up to Colerne. In October 1941 the road from the centre of the village up to the airfield at Carters Lane via Inghalls Cottages was made one-way only.[35]

Colerne continued in use after the war, closing in March 1976.

References

[1] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.2

[2] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, 2010, Folly Books, p.1. For photographs of the underground workings, both historic and recent, we thoroughly recommend this Nick McCamley book.

[3] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, 1982, Burnett Books, p.219

[4] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.2

[5] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.17-8 and Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.220

[6] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, p.64

[7] Wiltshire Life, February 2001

[8] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.41

[9] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.127-130

[10] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.14 and 20

[11] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.41

[12] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.5

[13] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, 1989, pub John Poulsom, p.23

[14] Nick McCamley, Second Workd War Secret Bunkers, 2010, Folly Books, p.41

[15] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.15-16

[16] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.5

[17] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.21-22, 38

[18] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.163

[19] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.146

[20] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.179

[21] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 28 January 1939

[22] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 April 1939

[23] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 April 1939

[24] The Wiltshire Times, 5 August 1939

[25] Richard Tombs, The English and their History, 2014, Allen Lane, p.687

[26] Courtesy Anna Grayson

[27] Courtesy Chris Potey

[28] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 June 1940

[29] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 7 January 1939

[30] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 2 March 1940

[31] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 19 August 1939

[32] Much of these details are indebted to David Berryman, Wiltshire Airfields in the Second World War, 2002, Countryside Books, p.63 and Chris Ashworth, Military Airfields of the South-West, 1982, Patrick Stephens Ltd, p.20 and p.66-68

[33] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 13 May 1939 and 20 May 1939

[34] Chris Ashworth, Military Airfields of the South-West, p.67

[35] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 18 October 1941

[1] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.2

[2] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, 2010, Folly Books, p.1. For photographs of the underground workings, both historic and recent, we thoroughly recommend this Nick McCamley book.

[3] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, 1982, Burnett Books, p.219

[4] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.2

[5] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.17-8 and Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.220

[6] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, p.64

[7] Wiltshire Life, February 2001

[8] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.41

[9] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.127-130

[10] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.14 and 20

[11] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.41

[12] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.5

[13] John Poulsom, The Ways of Corsham, 1989, pub John Poulsom, p.23

[14] Nick McCamley, Second Workd War Secret Bunkers, 2010, Folly Books, p.41

[15] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.15-16

[16] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.5

[17] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.21-22, 38

[18] Nick McCamley, Subterranean Britain: Second World War Secret Bunkers, p.163

[19] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.146

[20] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.179

[21] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 28 January 1939

[22] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 April 1939

[23] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 April 1939

[24] The Wiltshire Times, 5 August 1939

[25] Richard Tombs, The English and their History, 2014, Allen Lane, p.687

[26] Courtesy Anna Grayson

[27] Courtesy Chris Potey

[28] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 15 June 1940

[29] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 7 January 1939

[30] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 2 March 1940

[31] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 19 August 1939

[32] Much of these details are indebted to David Berryman, Wiltshire Airfields in the Second World War, 2002, Countryside Books, p.63 and Chris Ashworth, Military Airfields of the South-West, 1982, Patrick Stephens Ltd, p.20 and p.66-68

[33] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 13 May 1939 and 20 May 1939

[34] Chris Ashworth, Military Airfields of the South-West, p.67

[35] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 18 October 1941