|

Women and the Poor Laws

in the 1700s Barbara Davey August 2015 Life was hard if you were poor and a woman in the 1700s and it was made even harder by the laws relating to the Settlement of the Poor. Each parish had Church Wardens and Overseers of the Poor who controlled the distribution of parish relief. They collected money from those who could afford to give it and distributed it to those who they considered needed relief. To gain relief, men and single women had to apply to the parish where they had been born or had gained entitlement by other means. Married women (including widows) and unmarried women with children had to apply to the parish where their husband or the father of their children had been born or had entitlement. In other words, as soon as a man was involved in her life, a woman lost any rights of her own to parish relief. This happened to two of my ancestors. |

|

Unity Head

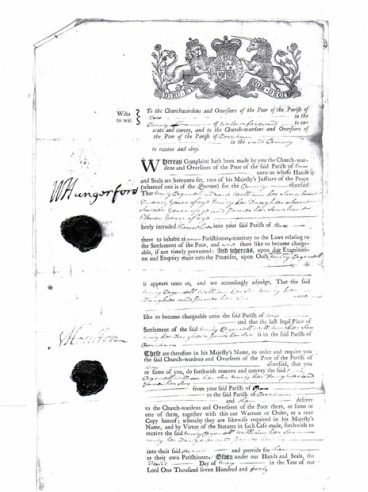

The first was my six-times great grandmother, Unity Head, who was born in 1683 in Box. In about 1706 she married John Cogswell and they had eight children. For the whole of their married life they lived in Corsham. John died in 1732. There is an indication from an oath that Unity swore in 1737 that the family were receiving parish relief from Corsham parish. The family continued to live in Corsham until Unity decided to move back to her place of birth, Box. We don’t know when the family moved but in May 1740 Unity and her three youngest children (aged 20, 16 and 11) are the subject of a Removal Order issued by the Justices of the Peace. The parish of Box was not prepared to pay out any relief money, even though Unity had been born there. So they were transported back to Corsham. Right: Removal Order dated 1740 for Unity Cogswell, Senior (nee Head) courtesy Barbara Davey Unity and John’s youngest son was James Cogswell, born 1728. In 1756 James married Joanna Salter in Box and they had at least five children, one of whom was named Unity, my four-times great grandmother. We cannot find Unity’s baptism but we estimate that she was born about 1764. |

Unity Cogswell

The first we definitely know about Unity Cogswell is in June1783 when she was the subject of a Removal Order. The Justices of the Peace interviewed her because she was about to become a burden on the Parish of Box. The reason for this was that she was pregnant but not married. We don’t know the family circumstances but assume that they were not able to support her and she would therefore need parish relief.

Her honesty at the interview about the name of the father of her child resulted in her being physically removed from Box by the churchwardens and taken to Batheaston in Somerset. This is where the father of her child lived and it was his parish which was required to support Unity and her baby. His name was James Stickland. We don’t know whether Unity had met him in Box or Batheaston. Perhaps she had been working in Batheaston and returned to Box when she had to stop working. But at 8 months pregnant, when she needed the love and support of her family, she was separated from them.

The first we definitely know about Unity Cogswell is in June1783 when she was the subject of a Removal Order. The Justices of the Peace interviewed her because she was about to become a burden on the Parish of Box. The reason for this was that she was pregnant but not married. We don’t know the family circumstances but assume that they were not able to support her and she would therefore need parish relief.

Her honesty at the interview about the name of the father of her child resulted in her being physically removed from Box by the churchwardens and taken to Batheaston in Somerset. This is where the father of her child lived and it was his parish which was required to support Unity and her baby. His name was James Stickland. We don’t know whether Unity had met him in Box or Batheaston. Perhaps she had been working in Batheaston and returned to Box when she had to stop working. But at 8 months pregnant, when she needed the love and support of her family, she was separated from them.

|

The Batheaston parish poor relief records still exist for this period and give an interesting insight into Unity’s plight. The churchwardens of Batheaston had arranged for lodgings for her. The first record shows a payment dated July 1783 To Hawkins, 5 weeks lodgings for Unity Cogswell for which Hawkins received 12 shillings and 6 pence. The next payment was to Unity herself: 3 weeks at 3 shillings a week.

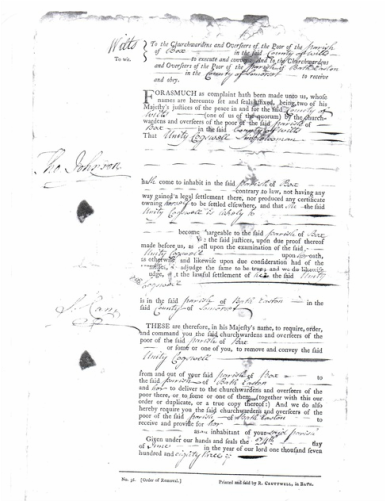

Unity’s baby was born in late July or early August 1783 and Dame Isaac received 5 shillings for delivering him. Unity baptised her son, Mark Cogswell, in Batheaston Church on 3rd August 1783. The recorder of payments was obviously keen to make sure the records were clear. After Mark’s birth, Unity received the sum of one shilling per week, recorded as To Unity Cogswell’s bastard by James Stickland. This same entry is written every week for two years. One gets the feeling that the man almost relished applying this stigma to Unity and baby Mark, who is never referred to by his name. It is pleasing to note that James Stickland contributed towards the upkeep of his son. Between 1783 and 1785 he paid the Overseers of the Poor a total of £4 and 4 shillings. Left: Removal Order dated 1783 for Unity Cogswell, Junior (courtesy Barbara Davey) |

Mark Alone

In October and November1785, there are payments to Unity because she was ill and, sadly, she died in Batheaston on 6 December 1785. Mark was just 2 years old. There is a payment recorded of 16 shillings and sixpence for Unity’s burial costs. This is interesting because Unity was actually buried in Box on 8 December, the entry reading Unity Cogswell, daughter of James and Joanna. It is good to know that they were able to bring their daughter home in the end.

However, young Mark remained in Batheaston and continued to receive poor relief payments: to Unity Cogswell’s bastard by Stickland still appearing every week until January 1797. Mark was then aged 13 and presumably deemed to be old enough to earn a wage and no longer eligible for poor relief.

We have yet to find out who looked after Mark after Unity died. Perhaps James Stickland arranged his care and this is why his payments towards Mark’s poor relief stopped when Unity died. However, we do know that the family in Box must have stayed in touch with him because, via a census carried out in Box in 1801, we find Mark living there with his aunt Jane, Unity’s sister, and her husband and working as a labourer.

In 1812 Mark Cogswell married Mary Gay in Box and they had five children. Mark died in 1832 aged 48.

In October and November1785, there are payments to Unity because she was ill and, sadly, she died in Batheaston on 6 December 1785. Mark was just 2 years old. There is a payment recorded of 16 shillings and sixpence for Unity’s burial costs. This is interesting because Unity was actually buried in Box on 8 December, the entry reading Unity Cogswell, daughter of James and Joanna. It is good to know that they were able to bring their daughter home in the end.

However, young Mark remained in Batheaston and continued to receive poor relief payments: to Unity Cogswell’s bastard by Stickland still appearing every week until January 1797. Mark was then aged 13 and presumably deemed to be old enough to earn a wage and no longer eligible for poor relief.

We have yet to find out who looked after Mark after Unity died. Perhaps James Stickland arranged his care and this is why his payments towards Mark’s poor relief stopped when Unity died. However, we do know that the family in Box must have stayed in touch with him because, via a census carried out in Box in 1801, we find Mark living there with his aunt Jane, Unity’s sister, and her husband and working as a labourer.

In 1812 Mark Cogswell married Mary Gay in Box and they had five children. Mark died in 1832 aged 48.