|

United Methodist Free Chapel,

Box Hill Alan Payne July 2022 The foundation of the Box Hill Methodist Chapel in 1868 was largely due to the work of the Box Hill quarry owners, the Pictor, Noble, Strong and Rowe families. The story of its origins is recorded at Methodist Churches. The purpose of this article is to tell the story of the members and the social history of the chapel until it closed in 1967. Methodism in Box was rapidly expanding in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Ebeneezer Chapel had been built in the centre of the village in 1834 and the Methodist authorities were then seeking to expand by building chapels in the hamlets. This was a time when the Church of England was under pressure locally, with the unpopular Rev Holled Darrell Cave Smith Webb Horlock, vicar of Box from 1831 until 1874. It was also a time when education was expanding and before the building of the National School in the centre of Box which happened several years later in 1875. The modern building is a residence (courtesy Carol Payne) |

Acquiring the Land

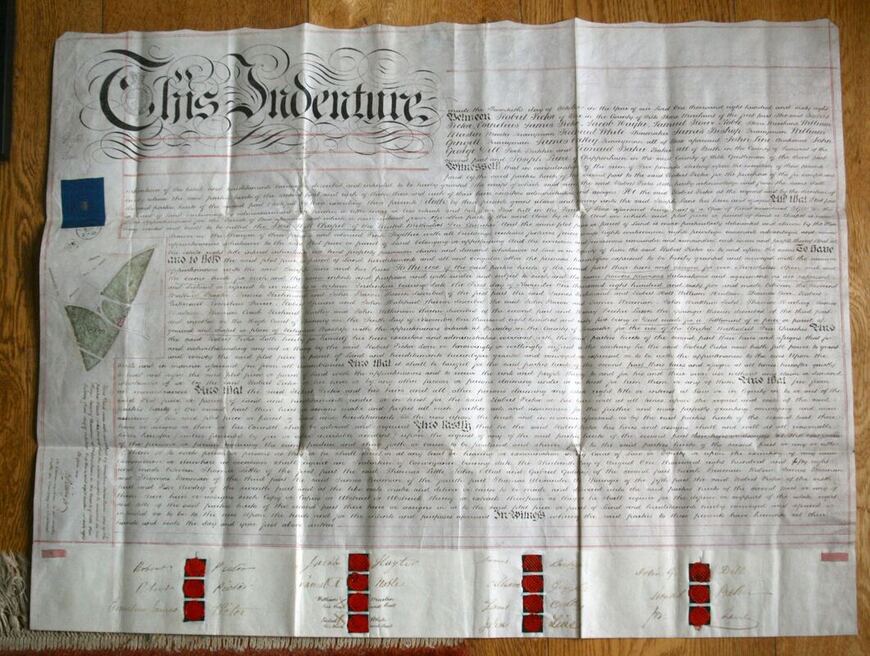

By an Indenture dated 20 October 1868 Robert Pictor, stone merchant, sold land (reference 390 on the Tithe Apportionment map) for the chapel for the sum of £5 to a prominent Chippenham accountant and Freemason who was deemed to be financially impeccable, Joseph Lane, gent. To ensure that there were no disputes in the title, Robert named others in the sale, including his family and other local quarry owners. He named these as himself, his brother Cornelius James, Jacob Hayter, Samuel Rowe Noble (all stone merchants), and others involved in Box Hill Methodism, including William Maslen (master quarryman who signed by making his mark), Richard White (shoemaker also made his mark), James Bishop, William Gingell and James Oatley (all quarryman), various Bath Methodists John Line (auctioneer), John George Dill (pork butcher) and Leonard Baker (baker).

By the date of the Indenture, the chapel was already in the course of construction to be known as The Box Hill Chapel of the United Methodist Free Churches. Joseph Lane was then authorised to transfer his title to trustees for the church which had been established in the High Court of Chancery.

By an Indenture dated 20 October 1868 Robert Pictor, stone merchant, sold land (reference 390 on the Tithe Apportionment map) for the chapel for the sum of £5 to a prominent Chippenham accountant and Freemason who was deemed to be financially impeccable, Joseph Lane, gent. To ensure that there were no disputes in the title, Robert named others in the sale, including his family and other local quarry owners. He named these as himself, his brother Cornelius James, Jacob Hayter, Samuel Rowe Noble (all stone merchants), and others involved in Box Hill Methodism, including William Maslen (master quarryman who signed by making his mark), Richard White (shoemaker also made his mark), James Bishop, William Gingell and James Oatley (all quarryman), various Bath Methodists John Line (auctioneer), John George Dill (pork butcher) and Leonard Baker (baker).

By the date of the Indenture, the chapel was already in the course of construction to be known as The Box Hill Chapel of the United Methodist Free Churches. Joseph Lane was then authorised to transfer his title to trustees for the church which had been established in the High Court of Chancery.

Chapel and Schoolroom

The Pictor family funded the building of the Box Hill Methodist Chapel at a cost of £296.10s for the church itself excluding the schoolhouse (£35,000 in today’s values) on a contract with builder C Gardener of Box.[1] They then sought to involve the local community in paying off the outstanding debt of about one-third of the cost.[2] There is no documentary information why the quarry owners saw the need for a local chapel but it was partly organic, as Methodist services had been held for several years on Box Hill in a nearby cottage or on the open ground of the common.[3] We can speculate that the new chapel was partly in response to sincere religious and moral principles but it also served a more commercial purpose. The original work was just the chapel but by 1871 a schoolroom was built as an extension to the chapel.[4] For the Pictor quarry-owners, there was a desire to have a more dependable and literate workforce and one of the attractions of the chapel was the schoolroom which offered literacy to children. Education was focused on stories considered to be socially and morally uplifting and on Bible texts. For adults there were also Penny Readings of Bible texts (popular Bible readings and entertainment on the admission charges of one penny going to charity).[5]

The schoolroom was large enough for some village activities and in 1876 a lantern show was put on showing eminent men of the past, including Chartist Richard Cobden, Abraham Lincoln and Dr Livingstone encountering a hippopotamus.[6] There were a few festive events for children, and usually such events under superintendent Barnett were accompanied by hymn singing and bible stories such as David and Goliath.[7] In 1883 a tea was organised for the children of members.[8] It wasn’t a grand event and the tea comprised cakes and bread and butter provided by Sister Mould for a fair attendance of children. Throughout its existence, teaching at the Sunday School concentrated on Bible study and depended on the dedication of a few people: George Hancock taught at Box Hill Sunday School for 50 years from 1903 to 1953 and Fred Neate for 56 years.[9] Other helpers included Mary Mould (1852-1895), Walter Sheppard Superintendent of Sunday School in 1937 and Mrs Ellen Head at the organ.

The schoolroom had other uses too, as the largest public room in the area it was a meeting place for club gatherings and important group events. Because the Pictor and Noble families were Liberals, a talk about Gladstone’s 50-years Work was put on in the schoolroom in 1887.[10]

Relevance of Chapel for Locals

At times the management of the church spilled over into petty legal disputes such as in 1887 when Elizabeth Sheppard sued William Dancey for the recovery of two volumes of Good and Pious Men, lent at a church service.[11] But, if local residents ever thought that the chapel was their church, they would have had to reconsider after the wedding of Rosina Maria Pictor in 1878.[12] The morning started with the firing of a canon to announce the special day and the small and primitive looking chapel was decorated by the members of the Independent Order of Good Templars (teetotal movement) with floral wreaths on the walls, triumphant arches spanning the road saying Crown them, Lord of All. The quarrymen were given the day off work and encouraged to attend the service, most left to listen outside. The service was conducted by ministers from Chippenham and Bath. The presents included everything needed by the couple, including a plated sardine box, honey jar with silver top and silver sugar tongs and tea caddy.

It is interesting to compare this with contemporary reports of the hardships endured underground by the stone quarry workers. Water ingress was commonplace, especially after heavy rainfall (dripping was scarcely a strong enough adjective), walking was difficult because of the trolley rails and sleepers for the small locomotive (numberless ruts and holes filled with puddles), Benzolene lamps carried to pick the route (made fitful by currents of air .. occasional blazing).[13]

The Pictor family funded the building of the Box Hill Methodist Chapel at a cost of £296.10s for the church itself excluding the schoolhouse (£35,000 in today’s values) on a contract with builder C Gardener of Box.[1] They then sought to involve the local community in paying off the outstanding debt of about one-third of the cost.[2] There is no documentary information why the quarry owners saw the need for a local chapel but it was partly organic, as Methodist services had been held for several years on Box Hill in a nearby cottage or on the open ground of the common.[3] We can speculate that the new chapel was partly in response to sincere religious and moral principles but it also served a more commercial purpose. The original work was just the chapel but by 1871 a schoolroom was built as an extension to the chapel.[4] For the Pictor quarry-owners, there was a desire to have a more dependable and literate workforce and one of the attractions of the chapel was the schoolroom which offered literacy to children. Education was focused on stories considered to be socially and morally uplifting and on Bible texts. For adults there were also Penny Readings of Bible texts (popular Bible readings and entertainment on the admission charges of one penny going to charity).[5]

The schoolroom was large enough for some village activities and in 1876 a lantern show was put on showing eminent men of the past, including Chartist Richard Cobden, Abraham Lincoln and Dr Livingstone encountering a hippopotamus.[6] There were a few festive events for children, and usually such events under superintendent Barnett were accompanied by hymn singing and bible stories such as David and Goliath.[7] In 1883 a tea was organised for the children of members.[8] It wasn’t a grand event and the tea comprised cakes and bread and butter provided by Sister Mould for a fair attendance of children. Throughout its existence, teaching at the Sunday School concentrated on Bible study and depended on the dedication of a few people: George Hancock taught at Box Hill Sunday School for 50 years from 1903 to 1953 and Fred Neate for 56 years.[9] Other helpers included Mary Mould (1852-1895), Walter Sheppard Superintendent of Sunday School in 1937 and Mrs Ellen Head at the organ.

The schoolroom had other uses too, as the largest public room in the area it was a meeting place for club gatherings and important group events. Because the Pictor and Noble families were Liberals, a talk about Gladstone’s 50-years Work was put on in the schoolroom in 1887.[10]

Relevance of Chapel for Locals

At times the management of the church spilled over into petty legal disputes such as in 1887 when Elizabeth Sheppard sued William Dancey for the recovery of two volumes of Good and Pious Men, lent at a church service.[11] But, if local residents ever thought that the chapel was their church, they would have had to reconsider after the wedding of Rosina Maria Pictor in 1878.[12] The morning started with the firing of a canon to announce the special day and the small and primitive looking chapel was decorated by the members of the Independent Order of Good Templars (teetotal movement) with floral wreaths on the walls, triumphant arches spanning the road saying Crown them, Lord of All. The quarrymen were given the day off work and encouraged to attend the service, most left to listen outside. The service was conducted by ministers from Chippenham and Bath. The presents included everything needed by the couple, including a plated sardine box, honey jar with silver top and silver sugar tongs and tea caddy.

It is interesting to compare this with contemporary reports of the hardships endured underground by the stone quarry workers. Water ingress was commonplace, especially after heavy rainfall (dripping was scarcely a strong enough adjective), walking was difficult because of the trolley rails and sleepers for the small locomotive (numberless ruts and holes filled with puddles), Benzolene lamps carried to pick the route (made fitful by currents of air .. occasional blazing).[13]

|

Independent Order of Good Templars (IOGT)

The founders of the Methodist Chapel were intent on a social crusade as well as a moral enlightenment through the work of the Independent Order of the Good Templars. Members of the organisation referred to themselves as Brothers and Sisters and saw similarities with the Knights Templar who went on Crusade to free the Holy Land from Moslem control and drank sour milk rather than be tempted by alcohol. From the start, the chapel had connections with the late Victorian movement against alcohol and the effect it had on families and lifestyles but heavy drinking was often part of the way of life for young quarrymen after hours of work underground extracting the stone. A pledge was taken of total abstinence and members would be given a password for use with other members.[14] Initiation into the movement required payment of a fee at a cost of 1 shilling for adult men and 6 pence for women and juveniles under 18. The Independent Order of Good Templars founded junior branches, such as the Lighthouse Lodge in Box in 1871. Numbers were never large (40 members in 1885, 70 in 1888, 40 in 1895) but they offered a continuity and moral authority to some of the aspiring families of Box Hill, including Maslen, Oatley, Walker and Hobbs – a devoted little band of hard workers doing a great and noble work.[15] |

By the 1880s, the IOGT was changing its focus from middle-class aspirating supporters to active social intervention. In July 1882, a summer meeting comprising an al fresco tea and luncheon gipsy fashion was held on Box Hill with officials from 16 lodges in Wiltshire representing 850 members and 982 juvenile members.[16] The Box Lighthouse Lodge was represented by Brothers Walter Oatley and William Mould. They had virtually no funds (£5.4s.4d) and no payment would be made to representatives, who were invited to tour the underground tunnels courtesy of Messrs Pictors and spend time in their mansion at Rudloe Towers where Miss L Pictor played the harmonium.

In 1903 the chapel decided to inaugurate a Christian Endeavour Society at the church.[17] The society had been founded in 1881 in the USA for young people as a way of giving them tools to deal with reconciling teenage angst and spiritual devotion. The society’s motto was For Christ and the Church, emphasising the need to commit to Christ’s life within a youth organisation, as exemplified by Prayers Chains where young people offered short prayers in succession as quickly as possible.

Changing Times

However, all was not harmonious in the management of the Methodist Chapel after 1900. The influence of the founding families, the Pictors and Nobles, had declined with changes in the quarrying trade, and others had moved their interest to the larger chapel in the centre of Box. An example of the discontent was in the charging of three youths, Thomas Tinson (aged 13), Albert Lucas (aged 12) and Albert Greenland (aged 11), with improper behaviour during a church service.[18] Their crime was laughing and talking during preaching and sitting down and leaning forward during singing of hymns but the case was thrown out for lack of evidence. We sometimes forget how introspective the lives of people were on the Hill. It was only in 1924 that a library of books was available to residents, donated by Mrs Leather Gulley of South London a relative of Dr Martin of Box, which were set up in the Chapel schoolroom.[19]

There were many changes of personnel at the church in the 1930s including the decline of the quarry-owners’ influence. In 1936 the death was reported of long-time caretaker of the church, Rhoda Robbins, wife of Frederick Robbins, coal haulier of Box Hill. Two years later came the death of one of the great stalwarts of Methodism in Box, Sister Lillian Lamb.[20] She was a goddaughter of William Booth (the founder of the Salvation Army) and she had helped with the building of the Methodist Church at Kingsdown and in the running of the Box Hill Church from 1923 until the early 1930s.[21] As a preacher and Wesleyan Deaconess, she had won the respect of most people for her compassion to the poor and her conviction in Christian virtues; one of the great inter-war women whose status in Box deserves more recognition.

Independent Order of Rechabites

New, middle-class people took control of the church leadership in the 1930s, largely led by Charles Oatley, auctioneer, and Frederick Neate of Hillcrest, both part of a second wave of teetotalism called The Independent Order of Rechabites. The Rechabite movement was not connected with the IOGT but had very similar aims. The word Rechab referred to the Israelite in the Old Testament, who commanded his children to drink no wine. Twentieth century members saw themselves as continuing a chain of abstinence.

The Box Tent (branch) was founded in 1906 at the Methodist Church schoolroom, originally calling itself Lifeboat, later changed to the more uplifting word Lighthouse.[22] In addition to Fred Neate, the earliest Box members were Fred Lucas (stone chopper) of 5 Boxfield Cottages, George Hancock (stone sawyer) and Samuel Gibbons. They had a thriving Friendly Society which could only be joined after signing The Pledge. Part of its appeal to upper middle-class members after 1927 was when the funds of the Wiltshire District Friendly Society were amalgamated, proving its financial stability.[23] Charles William Churchill (school teacher) from Corsham spoke in 1932 of how he had started as a Good Templar before becoming a Rechabite.[24]

A greater vigour was introduced into the church with the merger of the United Methodist church with similar groups in 1932. New people brought new ideas such as a Sale of Work in 1935 which involved fancy dress.[25] A Sacred Concert was held at Chapel in 1936 organised by Kathleen Milsom.[26] A musical service was held in October that year when J Swayne played the organ and C Kirkham sang Be Thou faithful unto Death, a programme that was much appreciated.[27] Mothers’ meetings were arranged by Mrs Maslen, helped by Mrs Manby, Mrs Head and Mrs Hillier in 1937, and one Sale of Work saw the ladies wearing old-English costumes and the men were attired in smocks of fustian and quaint hats.[28] The church was sufficiently well-regarded for Thomas Aust from 4, The Market Place to attend regularly to play the organ.[29]

In 1932 a new man came into the church, Frederick George Neate (1880-1960), who was the son of a quarryman from Berry House in 1891. He wasn’t an easy or even popular person, a man of unbending moral discipline who owned Box Hill Common having bought it in the inter-war years from the Northey family. He was on the Box Parish Council and tried to rationalise his ownership before losing a legal battle to the residents of Victory Cottage in 1932. Fred remained dedicated to the United Church and, on his death, set up a bequest to fund work on the church organ, a donation which later passed to the central village Box Methodist Church.

Michael Rumsey Wrote to us with these Modern Details

"The Box Hill, Kingsdown and central Box Methodist Churches all belonged to the Bath United Methodist Church Circuit until the 1932 act of union when all three branches in Methodism (the Wesleyans, Primitive Methodists and United Methodists) came together as The Methodist Church in the UK. The last service at Box Hill was on the evening of Sunday 12 November 1967, the same day as the closure of the Methodist Church at Kingsdown that afternoon. On the following Sunday, the congregation and Sunday School children boarded a Millers coach from Box Hill. The coach collected people at Tunnel Inn, Leafy Lane and on the main road on the lower Beech Road junction and transported them to the central Box Methodist Church for the service there.

Mrs Rose Evans played the organ in the morning and I played that evening and I've been there for the last 55 yrs plus 5 yrs at Box Hill so this November I shall see my Diamond Jubilee as organist in both Methodist Churches. My father was Church Steward, Sunday School Superintendent and Church Secretary at the church until its closure in 1967.

The organ at Box Hill was an early 19th century model by Flight and Robson which bore the brass plate which stated "Organ builders to His Majesty". After the church's closure it was sold to an organ builder in Newport and some pipework ended up in an instrument in Oswestry Methodist Church, but the main part of the organ, with the mahogany casework, was erected in Holy Trinity Parish Church Calne. Sadly this organ was destroyed by fire, an arson attack. Of course, the jewel in the crown is the present organ at Box Methodist Church, an 1850 Walker of London single manual tracker action instrument, with original pipework. It has a fine mahogany case which contains approximately 450 wooden and metal pipes. This organ description can be found on the National Church Organ Registry and the church building, plus the organ is now listed in the Box section of the new 3rd edition of Buildings of England, Wiltshire, edited by Julian Orbach".

The church came into the ownership of Ivan Brickell, who ran the Ice Cream Factory in The Ley. He converted the building into a private residence, as planned by architect Ken Oatley.[30] In 1973 it was being used as a gym for weight training.[31]

In 1903 the chapel decided to inaugurate a Christian Endeavour Society at the church.[17] The society had been founded in 1881 in the USA for young people as a way of giving them tools to deal with reconciling teenage angst and spiritual devotion. The society’s motto was For Christ and the Church, emphasising the need to commit to Christ’s life within a youth organisation, as exemplified by Prayers Chains where young people offered short prayers in succession as quickly as possible.

Changing Times

However, all was not harmonious in the management of the Methodist Chapel after 1900. The influence of the founding families, the Pictors and Nobles, had declined with changes in the quarrying trade, and others had moved their interest to the larger chapel in the centre of Box. An example of the discontent was in the charging of three youths, Thomas Tinson (aged 13), Albert Lucas (aged 12) and Albert Greenland (aged 11), with improper behaviour during a church service.[18] Their crime was laughing and talking during preaching and sitting down and leaning forward during singing of hymns but the case was thrown out for lack of evidence. We sometimes forget how introspective the lives of people were on the Hill. It was only in 1924 that a library of books was available to residents, donated by Mrs Leather Gulley of South London a relative of Dr Martin of Box, which were set up in the Chapel schoolroom.[19]

There were many changes of personnel at the church in the 1930s including the decline of the quarry-owners’ influence. In 1936 the death was reported of long-time caretaker of the church, Rhoda Robbins, wife of Frederick Robbins, coal haulier of Box Hill. Two years later came the death of one of the great stalwarts of Methodism in Box, Sister Lillian Lamb.[20] She was a goddaughter of William Booth (the founder of the Salvation Army) and she had helped with the building of the Methodist Church at Kingsdown and in the running of the Box Hill Church from 1923 until the early 1930s.[21] As a preacher and Wesleyan Deaconess, she had won the respect of most people for her compassion to the poor and her conviction in Christian virtues; one of the great inter-war women whose status in Box deserves more recognition.

Independent Order of Rechabites

New, middle-class people took control of the church leadership in the 1930s, largely led by Charles Oatley, auctioneer, and Frederick Neate of Hillcrest, both part of a second wave of teetotalism called The Independent Order of Rechabites. The Rechabite movement was not connected with the IOGT but had very similar aims. The word Rechab referred to the Israelite in the Old Testament, who commanded his children to drink no wine. Twentieth century members saw themselves as continuing a chain of abstinence.

The Box Tent (branch) was founded in 1906 at the Methodist Church schoolroom, originally calling itself Lifeboat, later changed to the more uplifting word Lighthouse.[22] In addition to Fred Neate, the earliest Box members were Fred Lucas (stone chopper) of 5 Boxfield Cottages, George Hancock (stone sawyer) and Samuel Gibbons. They had a thriving Friendly Society which could only be joined after signing The Pledge. Part of its appeal to upper middle-class members after 1927 was when the funds of the Wiltshire District Friendly Society were amalgamated, proving its financial stability.[23] Charles William Churchill (school teacher) from Corsham spoke in 1932 of how he had started as a Good Templar before becoming a Rechabite.[24]

A greater vigour was introduced into the church with the merger of the United Methodist church with similar groups in 1932. New people brought new ideas such as a Sale of Work in 1935 which involved fancy dress.[25] A Sacred Concert was held at Chapel in 1936 organised by Kathleen Milsom.[26] A musical service was held in October that year when J Swayne played the organ and C Kirkham sang Be Thou faithful unto Death, a programme that was much appreciated.[27] Mothers’ meetings were arranged by Mrs Maslen, helped by Mrs Manby, Mrs Head and Mrs Hillier in 1937, and one Sale of Work saw the ladies wearing old-English costumes and the men were attired in smocks of fustian and quaint hats.[28] The church was sufficiently well-regarded for Thomas Aust from 4, The Market Place to attend regularly to play the organ.[29]

In 1932 a new man came into the church, Frederick George Neate (1880-1960), who was the son of a quarryman from Berry House in 1891. He wasn’t an easy or even popular person, a man of unbending moral discipline who owned Box Hill Common having bought it in the inter-war years from the Northey family. He was on the Box Parish Council and tried to rationalise his ownership before losing a legal battle to the residents of Victory Cottage in 1932. Fred remained dedicated to the United Church and, on his death, set up a bequest to fund work on the church organ, a donation which later passed to the central village Box Methodist Church.

Michael Rumsey Wrote to us with these Modern Details

"The Box Hill, Kingsdown and central Box Methodist Churches all belonged to the Bath United Methodist Church Circuit until the 1932 act of union when all three branches in Methodism (the Wesleyans, Primitive Methodists and United Methodists) came together as The Methodist Church in the UK. The last service at Box Hill was on the evening of Sunday 12 November 1967, the same day as the closure of the Methodist Church at Kingsdown that afternoon. On the following Sunday, the congregation and Sunday School children boarded a Millers coach from Box Hill. The coach collected people at Tunnel Inn, Leafy Lane and on the main road on the lower Beech Road junction and transported them to the central Box Methodist Church for the service there.

Mrs Rose Evans played the organ in the morning and I played that evening and I've been there for the last 55 yrs plus 5 yrs at Box Hill so this November I shall see my Diamond Jubilee as organist in both Methodist Churches. My father was Church Steward, Sunday School Superintendent and Church Secretary at the church until its closure in 1967.

The organ at Box Hill was an early 19th century model by Flight and Robson which bore the brass plate which stated "Organ builders to His Majesty". After the church's closure it was sold to an organ builder in Newport and some pipework ended up in an instrument in Oswestry Methodist Church, but the main part of the organ, with the mahogany casework, was erected in Holy Trinity Parish Church Calne. Sadly this organ was destroyed by fire, an arson attack. Of course, the jewel in the crown is the present organ at Box Methodist Church, an 1850 Walker of London single manual tracker action instrument, with original pipework. It has a fine mahogany case which contains approximately 450 wooden and metal pipes. This organ description can be found on the National Church Organ Registry and the church building, plus the organ is now listed in the Box section of the new 3rd edition of Buildings of England, Wiltshire, edited by Julian Orbach".

The church came into the ownership of Ivan Brickell, who ran the Ice Cream Factory in The Ley. He converted the building into a private residence, as planned by architect Ken Oatley.[30] In 1973 it was being used as a gym for weight training.[31]

Conclusion

The Methodist chapel was once the centre of life on Box Hill for many residents who wanted to worship together and have a meeting place away from alcohol in the pubs at The Rising Sun and the Quarryman's Arms. For many years the style of religious service offered at the chapel reflected the beliefs and ethos of a few leading individuals. The openness of the original "Meeting House" movement became restricted to the attitudes of those individuals, encouraging a second chapel The Primative Methodist chapel. Both have now disappeared but, fortunately, the buildings themselves have been saved for posterity and exist as a tribute to the people of Box Hill during the century that they existed for worship.

The Methodist chapel was once the centre of life on Box Hill for many residents who wanted to worship together and have a meeting place away from alcohol in the pubs at The Rising Sun and the Quarryman's Arms. For many years the style of religious service offered at the chapel reflected the beliefs and ethos of a few leading individuals. The openness of the original "Meeting House" movement became restricted to the attitudes of those individuals, encouraging a second chapel The Primative Methodist chapel. Both have now disappeared but, fortunately, the buildings themselves have been saved for posterity and exist as a tribute to the people of Box Hill during the century that they existed for worship.

References

[1] The Shepton Mallet Journal, 26 June 1868

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 30 June 1870

[3] The Wiltshire Independent, 22 October 1868

[4] Daily Bristol Times and Mirror, 21 April 1871

[5] The Wiltshire Independent, 10 and 26 November 1868

[6] The North Wilts Herald, 18 November 1876

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 16 April 1881

[8] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 12 May 1883

[9] Somerset Guardian and Radstock Observer, 2 April 1953

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 6 August 1887

[11] The Western Daily Press, 22 August 1887

[12] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 30 March 1878

[13] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 29 July 1882

[14] Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, 31 October 1885

[15] The Bristol Mercury, 26 November 1888 and Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 26 July 1888

[16] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 29 July 1882

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 28 November 1903

[18] The Wiltshire Times, 21 April 1900

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 6 September 1924

[20] The Wiltshire Times, 26 March 1938

[21] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 September 1923

[22] The Wiltshire Times, 28 July 1906

[23] The North Wilts Herald, 1 April 1927

[24] The Wiltshire Times, 8 October 1932

[25] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 2 November 1935

[26] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 12 December 1936

[27] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 October 1936

[28] The Wiltshire Times, 2 November 1935

[29] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 27 July 1935

[30] Courtesy Ken Oatley

[31] Courtesy Steve Oregan

[1] The Shepton Mallet Journal, 26 June 1868

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 30 June 1870

[3] The Wiltshire Independent, 22 October 1868

[4] Daily Bristol Times and Mirror, 21 April 1871

[5] The Wiltshire Independent, 10 and 26 November 1868

[6] The North Wilts Herald, 18 November 1876

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 16 April 1881

[8] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 12 May 1883

[9] Somerset Guardian and Radstock Observer, 2 April 1953

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 6 August 1887

[11] The Western Daily Press, 22 August 1887

[12] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 30 March 1878

[13] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 29 July 1882

[14] Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard, 31 October 1885

[15] The Bristol Mercury, 26 November 1888 and Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 26 July 1888

[16] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 29 July 1882

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 28 November 1903

[18] The Wiltshire Times, 21 April 1900

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 6 September 1924

[20] The Wiltshire Times, 26 March 1938

[21] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 September 1923

[22] The Wiltshire Times, 28 July 1906

[23] The North Wilts Herald, 1 April 1927

[24] The Wiltshire Times, 8 October 1932

[25] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 2 November 1935

[26] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 12 December 1936

[27] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 October 1936

[28] The Wiltshire Times, 2 November 1935

[29] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 27 July 1935

[30] Courtesy Ken Oatley

[31] Courtesy Steve Oregan