Unemployment Alan Payne March 2022

British politics in the aftermath of the Great War were evolutionary and some historians say that they came close to revolutionary.[1] Fear of the Russian Revolution caused a swing to the right of many establishment figures. The aftermath of the Easter Rising in Ireland caused a civil war in Ireland in 1922-23. The appointment of Ramsay Macdonald as the first Labour Prime Minister in 1924 brought a new party to the fore in national British politics. But the underlying British problem was social and economic, not politics at all. The problem was how to cure the economic depression which had put so many out of work.

Political Situation in Box

The Irish problem had fatal consequences in Box and resulted in the deaths of at least two Box men, Herbert Percy Hancock on 21 October 1918 and Reginald Isaac Hancock on 3 November 1918, in the final days of the Great War. We know that they were involved in the troubles in Ireland because both were described as dying on the Home Front, rather than the European or Far Eastern conflicts. Herbert is reputed to have been killed on a ship coming home from Ireland, just 18 years old.[2]

The issue of whether they died as a result of the Great War or because of internal security issues caused a delay in naming them as part of Box’s war deaths. The government accepted that war deaths included those who fell because of friendly fire and those killed as a result of accidents whilst in service. Eventually, it was accepted that they should be included in the roll of honour.

The Irish problem had fatal consequences in Box and resulted in the deaths of at least two Box men, Herbert Percy Hancock on 21 October 1918 and Reginald Isaac Hancock on 3 November 1918, in the final days of the Great War. We know that they were involved in the troubles in Ireland because both were described as dying on the Home Front, rather than the European or Far Eastern conflicts. Herbert is reputed to have been killed on a ship coming home from Ireland, just 18 years old.[2]

The issue of whether they died as a result of the Great War or because of internal security issues caused a delay in naming them as part of Box’s war deaths. The government accepted that war deaths included those who fell because of friendly fire and those killed as a result of accidents whilst in service. Eventually, it was accepted that they should be included in the roll of honour.

Great War heroes buried in Box Cemetery: left HP Hancock and right RI Hancock

Fear of Revolution

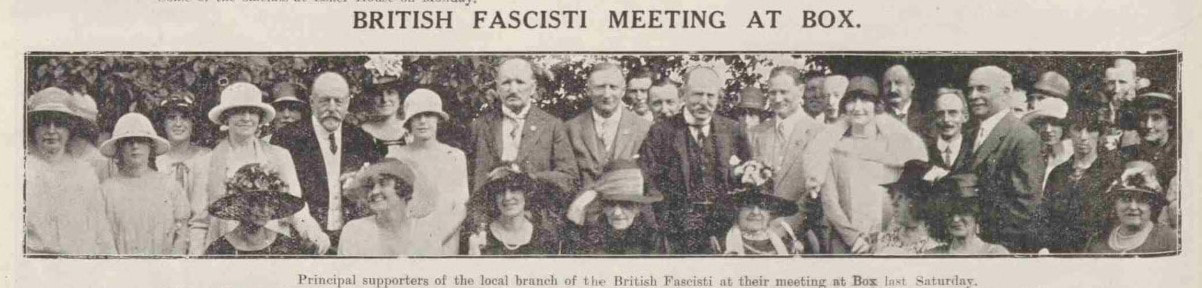

Box was in a state of great distress in the inter-war period. Fear of a communist take-over nationally caused a marked swing to the right in Box’s establishment. The lord of the manor and the village’s vicar were active in forming the Box branch of the British Fascisti movement, the first movement in Britain to claim to be Fascists. George Edward Northey was appointed Officer Commanding the group (we would say chairman) and Mr F Scott as Organising Secretary and Recruiter. Rev George Foster couldn’t attend the meeting at Rudloe Park but wrote in support of the movement.

The British Fascisti movement was founded in 1923, aiming to replicate Mussolini’s March on Rome. It was a broad-ranging movement to refute the rise of socialism in Britain and its leader, General RBD Blakeney, claimed that it was modelled on the structure used by the Boy Scouts movement. It had a limited political agenda and was more a statement of intend, defenders of the British Empire initiative and predominantly upper class. In today’s parlance, it was more like an affiliated branch of the Conservative Party advocating National Conservatism and quickly distanced itself from the excesses of fascism in Europe by 1927, before Oswald Moseley’s later movement. I have found no other references to its existence in Box after 1925.

Box was in a state of great distress in the inter-war period. Fear of a communist take-over nationally caused a marked swing to the right in Box’s establishment. The lord of the manor and the village’s vicar were active in forming the Box branch of the British Fascisti movement, the first movement in Britain to claim to be Fascists. George Edward Northey was appointed Officer Commanding the group (we would say chairman) and Mr F Scott as Organising Secretary and Recruiter. Rev George Foster couldn’t attend the meeting at Rudloe Park but wrote in support of the movement.

The British Fascisti movement was founded in 1923, aiming to replicate Mussolini’s March on Rome. It was a broad-ranging movement to refute the rise of socialism in Britain and its leader, General RBD Blakeney, claimed that it was modelled on the structure used by the Boy Scouts movement. It had a limited political agenda and was more a statement of intend, defenders of the British Empire initiative and predominantly upper class. In today’s parlance, it was more like an affiliated branch of the Conservative Party advocating National Conservatism and quickly distanced itself from the excesses of fascism in Europe by 1927, before Oswald Moseley’s later movement. I have found no other references to its existence in Box after 1925.

Economics in 1920s Box

The 1920s and 1930s in Box were dominated by problems: unemployment, insufficient food and economic decline in the village’s staple industries. The problem was partly national economic circumstances with lack of investment in new technology and falling demand. Britain’s decision to peg the pound to the gold standard meant that £1 was equivalent to US $4.85, resulting in deflation, encouraging purchases to be deferred awaiting lower prices.

Box was still substantially rural and dependent on the farming industry. Agriculture started well enough with a huge boost to farmers in the later years of the war. The Corn Production Act of 1917 ended free trade in corn and oats for a 5-year period, guaranteeing fixed prices linked to the cost of production. The aim was to encourage British production and lessen reliance on overseas imports which had risen to 80% of national need. The Smallholdings Acts of 1916 and 1918 encouraged local councils to expand small-scale farming locally and was open to soldiers disabled in the conflict and servicemen returning from war.

The euphoria of peace and a short-lived boom lasted only a year or so. By 1921 it had all gone wrong because sales prices of corn had fallen by 50% and the government was forced to reverse its previous policies. The Agriculture Minimum Wages commitment was abandoned and farming slipped into recession with lower land values, poverty amongst tenants and workers and reduced investment in methods of production and residential properties. George Pritchard at Ashley Farm had struggled through the worst years of agricultural depression after 1880 but was obliged to relinquish the tenancy when the landlord sold up in 1919. The situation was equally bad for employees whose wages had not kept up with wartime inflation. In January 1919 a meeting of the Workers’ Union was called at The Bear Inn, with all agricultural workers urged to attend, to hear speaker Mr Keen, the district organiser.[3]

The mood of militancy spread to other sectors of the economy in Box with continuing demobilisation of servicemen and growing enthusiasm for the successes seen in the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.[4] In 1918 Sylvia Pankhurst was able to compare her view of Russian house building with the appalling conditions in Britain: Where houses are scarce house accommodation is rationed on the basis of one room for every adult and one room for two children. If a family for any reason is not able to obtain furniture, light, or fuel, the community provides these without charge.[5] In Box the stone quarry trade was coming to a halt and ex-employees like Cecil Lambert couldn’t return to their former jobs and had to seek alternatives. Stone workers went on strike in Box in September 1921, an unprecedented event in Victorian quarries.[6] Mr Keen claimed that all the masons and sawyers were on strike in Box and Corsham.

Starvation in Box

In 1921-22 it is estimated that 2 million British workers were suffering unemployment and, after a moderate recovery, the situation worsened with the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the severe depression of the 1930s with over 3 million unemployed. None of these figures included agricultural labourers or the self-employed, who were the majority of workers in Box, because they were outside the provisions of the National Insurance Act of 1911.

Of course, the situation in the Box stone industry had been highly cyclical in the years prior to the Great War. As early as 1901, some banker masons in Box and Corsham felt that they were underpaid and demanded an extra 7d per hour rather than the ½d offered.[7] They went out on strike for a month and a half until late July 1901 when It is estimated that the (Box) men have lost in wages alone close on £700.[8] What was different was the realisation that the decline wasn’t temporary. In November 1908 vicar Rev William White was fundraising to rebuild the church wall and thus provide work for several men who have for so long been unemployed. Nearly a dozen men are already employed on the work and for some weeks I felt that to give employment to a few would be better than a promiscuous charity to many.[9] Traditionally, winter was problematic for employment and in January 1909 a soup kitchen was started every Tuesdays and Fridays to support families in need of food.

The 1904 recession lasted until 1910 when offers of work began to pick up but the entire economic situation was irreversibly altered by the war. Many skilled workers left the trade, some emigrating, including PM Cogswell and Alfred Harding who left Box in 1906 to make their fortune in Pennsylvania as stone masons. Richard Head told us his great uncle Sid Chandler emigrated to Australia in 1910 when he was 23 years-old. He sailed on 16 November 1910 aboard the SS Runic, part of the White Star Line, sailing out of Liverpool and headed for Adelaide.

By 1920 the best stone had been extracted and the stonemason’s trade was declining with a reduction in house building nationally. By 1923 vicar Rev HDS Sweetapple was warning of forces at work making for the breakup of our civilisation.[10] There seemed to be no answer: May God stir Box to cast off lethargy and carelessness and awake our highest interests. By February 1924, emigration seemed a sensible solution: We would remind any lads thinking of seeking a career in another land of the splendid opportunities offered by the Australian Government to boys if between the ages of 15 and 18 years.[11]

The great estates continued to be sold off, including the Northey Estate Sales of 1919 and 1923. By 1934, even the employers recognised the end when the quarrymen’s houses at Fairmead View, Mill Lane and Bath Road were all sold by The Firms (Box’s name for the all-dominating Bath Stone Firms Limited), who no longer needed houses for their employees. The decline was permanent. Longsplatt Quarry shut in 1920, the small quarries opposite The Swan pub in 1924. It wasn’t just the farming and stone trade. A number of the larger businesses in Box closed in the 1920s: the Brewery in the Market Place in 1924, and the Candle and Soap Factory at Quarry Hill in 1930.

This background of economic decline shaped the Box economy after the war. The dole (meaning a state share-out) was simply not available for most workers in the village. Instead, they had to rely on the old Poor Law and the Union Workhouse in Chippenham or private parish charity. The census records a similar decline from 2,405 people in 1901 down to 2,120 in 1921, a level similar to that in Box in 1871. One of the remarkable aspects of the inter-war period was the increase in charity throughout Britain despite the hardship and poverty experienced. Box continued many of the fundraising measures experienced during the Great War. These included picking primroses which were shipped to Liverpool for sale there. It raised £10.10s for charities in 1927 and in 1929, 200 bunches were picked and a profit of £12.10s.6d was realised.[12]

The Easter church collection was traditionally gifted to the needy in the parish but in 1929 general poverty resulted in the collection being sadly insufficient to meet the need for extra help.[13] So wealthy individuals donated money: the Hon Mrs Twisleton £5.15s, Mr Shaw Mellor £5, Mrs JW Hooper 5s, and Mrs Montgomery Campbell £2 for coal. The Christmas church collection was also donated to the sick and needy – in 1929 amounting to £15.18s.6d.[14] Because the vicar George Foster was required to take time off to recuperate after two operations in 1929, various local events were cancelled. Instead, Miss Batterbury arranged a house-to-house collection in support of the cancelled Box Revels to support the school.[15]

Traditional fundraising in the village was to support the Royal United Hospital in Bath. In May 1927 the village donated 1,178 eggs to the hospital, the highest total ever.[16] This became the norm for the inter-war years and in 1933 the Harvest Thanksgiving Services enabled fruit and vegetables to be taken to the Children’s Orthopaedic Hospital, Bath, and the Holy Innocents’ Home in Box.[17] The collections were, as usual, for the Royal United Hospital, Bath.

The 1920s and 1930s in Box were dominated by problems: unemployment, insufficient food and economic decline in the village’s staple industries. The problem was partly national economic circumstances with lack of investment in new technology and falling demand. Britain’s decision to peg the pound to the gold standard meant that £1 was equivalent to US $4.85, resulting in deflation, encouraging purchases to be deferred awaiting lower prices.

Box was still substantially rural and dependent on the farming industry. Agriculture started well enough with a huge boost to farmers in the later years of the war. The Corn Production Act of 1917 ended free trade in corn and oats for a 5-year period, guaranteeing fixed prices linked to the cost of production. The aim was to encourage British production and lessen reliance on overseas imports which had risen to 80% of national need. The Smallholdings Acts of 1916 and 1918 encouraged local councils to expand small-scale farming locally and was open to soldiers disabled in the conflict and servicemen returning from war.

The euphoria of peace and a short-lived boom lasted only a year or so. By 1921 it had all gone wrong because sales prices of corn had fallen by 50% and the government was forced to reverse its previous policies. The Agriculture Minimum Wages commitment was abandoned and farming slipped into recession with lower land values, poverty amongst tenants and workers and reduced investment in methods of production and residential properties. George Pritchard at Ashley Farm had struggled through the worst years of agricultural depression after 1880 but was obliged to relinquish the tenancy when the landlord sold up in 1919. The situation was equally bad for employees whose wages had not kept up with wartime inflation. In January 1919 a meeting of the Workers’ Union was called at The Bear Inn, with all agricultural workers urged to attend, to hear speaker Mr Keen, the district organiser.[3]

The mood of militancy spread to other sectors of the economy in Box with continuing demobilisation of servicemen and growing enthusiasm for the successes seen in the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.[4] In 1918 Sylvia Pankhurst was able to compare her view of Russian house building with the appalling conditions in Britain: Where houses are scarce house accommodation is rationed on the basis of one room for every adult and one room for two children. If a family for any reason is not able to obtain furniture, light, or fuel, the community provides these without charge.[5] In Box the stone quarry trade was coming to a halt and ex-employees like Cecil Lambert couldn’t return to their former jobs and had to seek alternatives. Stone workers went on strike in Box in September 1921, an unprecedented event in Victorian quarries.[6] Mr Keen claimed that all the masons and sawyers were on strike in Box and Corsham.

Starvation in Box

In 1921-22 it is estimated that 2 million British workers were suffering unemployment and, after a moderate recovery, the situation worsened with the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the severe depression of the 1930s with over 3 million unemployed. None of these figures included agricultural labourers or the self-employed, who were the majority of workers in Box, because they were outside the provisions of the National Insurance Act of 1911.

Of course, the situation in the Box stone industry had been highly cyclical in the years prior to the Great War. As early as 1901, some banker masons in Box and Corsham felt that they were underpaid and demanded an extra 7d per hour rather than the ½d offered.[7] They went out on strike for a month and a half until late July 1901 when It is estimated that the (Box) men have lost in wages alone close on £700.[8] What was different was the realisation that the decline wasn’t temporary. In November 1908 vicar Rev William White was fundraising to rebuild the church wall and thus provide work for several men who have for so long been unemployed. Nearly a dozen men are already employed on the work and for some weeks I felt that to give employment to a few would be better than a promiscuous charity to many.[9] Traditionally, winter was problematic for employment and in January 1909 a soup kitchen was started every Tuesdays and Fridays to support families in need of food.

The 1904 recession lasted until 1910 when offers of work began to pick up but the entire economic situation was irreversibly altered by the war. Many skilled workers left the trade, some emigrating, including PM Cogswell and Alfred Harding who left Box in 1906 to make their fortune in Pennsylvania as stone masons. Richard Head told us his great uncle Sid Chandler emigrated to Australia in 1910 when he was 23 years-old. He sailed on 16 November 1910 aboard the SS Runic, part of the White Star Line, sailing out of Liverpool and headed for Adelaide.

By 1920 the best stone had been extracted and the stonemason’s trade was declining with a reduction in house building nationally. By 1923 vicar Rev HDS Sweetapple was warning of forces at work making for the breakup of our civilisation.[10] There seemed to be no answer: May God stir Box to cast off lethargy and carelessness and awake our highest interests. By February 1924, emigration seemed a sensible solution: We would remind any lads thinking of seeking a career in another land of the splendid opportunities offered by the Australian Government to boys if between the ages of 15 and 18 years.[11]

The great estates continued to be sold off, including the Northey Estate Sales of 1919 and 1923. By 1934, even the employers recognised the end when the quarrymen’s houses at Fairmead View, Mill Lane and Bath Road were all sold by The Firms (Box’s name for the all-dominating Bath Stone Firms Limited), who no longer needed houses for their employees. The decline was permanent. Longsplatt Quarry shut in 1920, the small quarries opposite The Swan pub in 1924. It wasn’t just the farming and stone trade. A number of the larger businesses in Box closed in the 1920s: the Brewery in the Market Place in 1924, and the Candle and Soap Factory at Quarry Hill in 1930.

This background of economic decline shaped the Box economy after the war. The dole (meaning a state share-out) was simply not available for most workers in the village. Instead, they had to rely on the old Poor Law and the Union Workhouse in Chippenham or private parish charity. The census records a similar decline from 2,405 people in 1901 down to 2,120 in 1921, a level similar to that in Box in 1871. One of the remarkable aspects of the inter-war period was the increase in charity throughout Britain despite the hardship and poverty experienced. Box continued many of the fundraising measures experienced during the Great War. These included picking primroses which were shipped to Liverpool for sale there. It raised £10.10s for charities in 1927 and in 1929, 200 bunches were picked and a profit of £12.10s.6d was realised.[12]

The Easter church collection was traditionally gifted to the needy in the parish but in 1929 general poverty resulted in the collection being sadly insufficient to meet the need for extra help.[13] So wealthy individuals donated money: the Hon Mrs Twisleton £5.15s, Mr Shaw Mellor £5, Mrs JW Hooper 5s, and Mrs Montgomery Campbell £2 for coal. The Christmas church collection was also donated to the sick and needy – in 1929 amounting to £15.18s.6d.[14] Because the vicar George Foster was required to take time off to recuperate after two operations in 1929, various local events were cancelled. Instead, Miss Batterbury arranged a house-to-house collection in support of the cancelled Box Revels to support the school.[15]

Traditional fundraising in the village was to support the Royal United Hospital in Bath. In May 1927 the village donated 1,178 eggs to the hospital, the highest total ever.[16] This became the norm for the inter-war years and in 1933 the Harvest Thanksgiving Services enabled fruit and vegetables to be taken to the Children’s Orthopaedic Hospital, Bath, and the Holy Innocents’ Home in Box.[17] The collections were, as usual, for the Royal United Hospital, Bath.

General Strike, May 1926

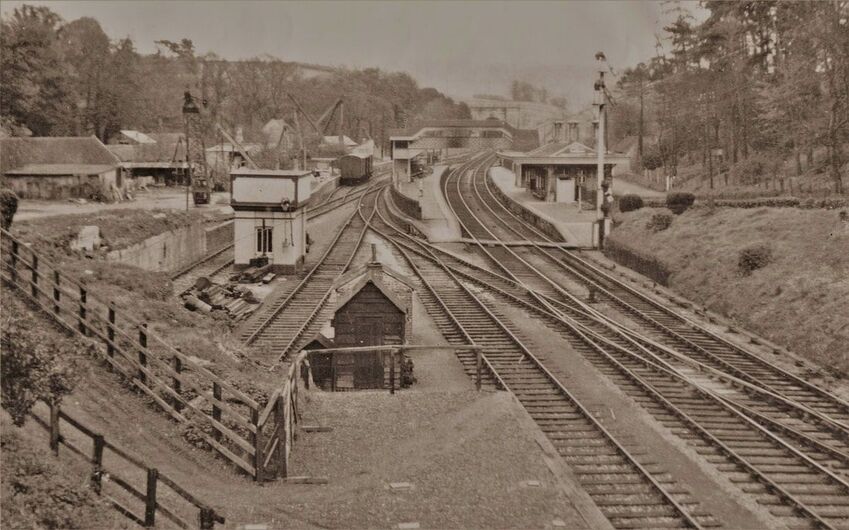

The national recession disguised the fact that many industries were suffering structural unemployment because they were diminishing or becoming obsolete. The national General Strike of May 1926 lasted only nine days but its consequences were significant. About one and a half million workers came out on strike, including employees of local newspaper printers, the Bath Electric Tramway Company and the Great Western Railways, particularly the signalmen, which effectively locked down transport in Box, although volunteers tried to keep sketchy services going.[18] Stella Clarke recalled miners marching through the centre of Box before climbing up Box Hill and turning to Lower Rudloe where they took off their boots and sat down on the roadside.

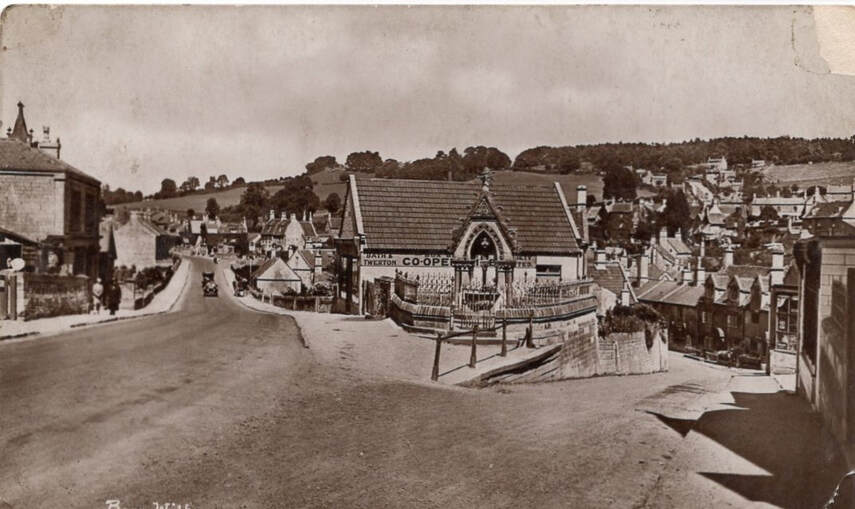

It was no coincidence that the Co-operative Society shop opened in 1925; it was perceived as a mutual help organisation supplying vital necessities to people in need. The Bath and Twerton Branch at Colerne was closed and moved down to the centre of Box, which proved to very successful in providing needs, including Free Death Benefits and a Convalescent Fund for those recovering from illness.[19] They were much more than a retail outlet and in May 1926 organised a group ramble in Box.[20] Those coming from Bath marvelled at the light railway which used to convey stone from the quarries at Monkton Farleigh to the railway siding at Box Station, then past where the old 1st Volunteer Regiment held their annual camp and back to Box via the Horse and Jockey Road. The group were taken to see the remains of the (Roman) tessellated pavement then into the Wilderness Gardens. They went back to Shockerwick to the main road where the trams were reached.

The miners’ strike affected coal supplies in the village. Much coal was imported from the Somerset Coal Fields which suddenly dried up, leaving their workers with no income at all. The Co-operative Society made a grant of £20 to the Somerset Coalfield Distress Fund and increased this in August 1926 by an additional £30 to the Co-operative Union Relief Fund for Societies in Mining Areas.[21] In late May 1926, the parish magazine was able to record: We are grateful that the strike was over and every speaker was able to be present at the World Call to the Church held in Bristol.[22]

But there was no relief for the unemployed: in 1929 There is a lot of unemployment and distress in Box at present .. Donations, large or small, will be welcomed. If you have a comfortable room and plenty of coal, give a thought to those who have, in many cases, only 10s a week Old Age Pension, out of which there has to come rent, fuel and food.[23]

Box Employment Scheme, 1933

The Nightmare of Unemployment which characterised Britain in the 1930s was felt deeply in Box. In August 1932 the parish magazine recorded: The spectre of unemployment is still with us … men out of employment only receive from the State sufficient for bare existence. They soon get despondent, nervy and even reckless.[24] There was some work at times of agricultural activity in the spring plant and autumn harvesting but the vicar wrote: We in Box should be working out some scheme whereby our fellow men might find employment in the year when work is slack. The parish magazine recorded that many villages, especially in Buckinghamshire had set up local initiatives.

Three local men took the local initiative to find work for villagers: RA Legard, AHF Hillier and HE Sykes. They were very different people but with the same cause. Captain Roger Alexander Legard (15 June 1891 - 29 January 1972), was a bachelor who lived at Merrington, Kingsdown who had moved to Box in the early 1930s and quickly became well-known for his work as secretary of the Box British Legion, reading out the Roll of Honour at Remembrance Day Services and organiser of the Poppy Day Collections.[25] In later times he was chairman of the Box Planning Committee, tasked with rebuilding the area after the Second World War, and a representative on the Calne and Chippenham Rural District Council.[26] In the 1930s the register of any employer who could offer work was kept by Roger Legard. Arthur Hulbert Frederick Hillier (1887 – 8 November 1950) was a boot repairer and retailer, who traded in The Parade and later from Dalebrook, Market Place.[27] He was a Methodist and the family were connected to Murray & Baldwin in the Market Place.[28] Arthur’s role was to keep the list of men needing work. Colonel Harry Erling Sykes (born in York in 1872 and died 7 March 1955) was a career soldier serving in the Army Service Corps before the First World War. He later lived at Ashley Cottage and was a founder member of the Comrades Club in the 1920s. He was credited with launching the Box Employment Scheme in May 1933 and he administered the funds.[29] Captain Legard and Colonel Sykes also took an active role in preparations for the Home Guard defence during World War II.[30]

Together these three started the Box Employment Fund in May 1933 as Unemployment is one of the most universal and terrible diseases of modern life. The parish magazine promoted their activities: They felt that if they could only find or make work for 10 men it would be doing some little to help. Their venture of faith has been abundantly justified by results.[31] They planned to put unemployed workers in touch with potential employers and to increase the amount of work available. To do this they needed to be advised of any work and to keep a register of men wanting work and their skills (mostly casual labourers and stone workers). Box organisations raised funds to promote new work with small-scale local events, whist-drives, jumble sales and performances in the Bingham Hall. The aim was to fund institutional work rather than grants to the unemployed. By August 1933, £47 had been raised (although the promoters had targeted £100) and in the summer 4,000 hours of casual work had been supplied in the village.[32] But these measures provided no upturn in the economy.

Conclusion

Unemployment benefit paid to those without work in 1928-30 was reduced in 1931 because of the excessive cost for the national economy. Governments were committed to balancing the national budget and unwilling to contemplate what later became known as “deficit financing” (expenditure finance through state borrowings). The cut was restored in 1934, shortly after the upturn in the economy, which was prompted by low interest rates, the growth of the so-called “new” consumer industries and not least, a massive building boom. The consequence was a remarkable turnaround in living standards. As work returned for military duties so an additional upsurge continued with falling prices after 1935. As sometimes happens in short, sharp recessions, the upturn was equally quick. Box was booming in the late 1930s.

The national recession disguised the fact that many industries were suffering structural unemployment because they were diminishing or becoming obsolete. The national General Strike of May 1926 lasted only nine days but its consequences were significant. About one and a half million workers came out on strike, including employees of local newspaper printers, the Bath Electric Tramway Company and the Great Western Railways, particularly the signalmen, which effectively locked down transport in Box, although volunteers tried to keep sketchy services going.[18] Stella Clarke recalled miners marching through the centre of Box before climbing up Box Hill and turning to Lower Rudloe where they took off their boots and sat down on the roadside.

It was no coincidence that the Co-operative Society shop opened in 1925; it was perceived as a mutual help organisation supplying vital necessities to people in need. The Bath and Twerton Branch at Colerne was closed and moved down to the centre of Box, which proved to very successful in providing needs, including Free Death Benefits and a Convalescent Fund for those recovering from illness.[19] They were much more than a retail outlet and in May 1926 organised a group ramble in Box.[20] Those coming from Bath marvelled at the light railway which used to convey stone from the quarries at Monkton Farleigh to the railway siding at Box Station, then past where the old 1st Volunteer Regiment held their annual camp and back to Box via the Horse and Jockey Road. The group were taken to see the remains of the (Roman) tessellated pavement then into the Wilderness Gardens. They went back to Shockerwick to the main road where the trams were reached.

The miners’ strike affected coal supplies in the village. Much coal was imported from the Somerset Coal Fields which suddenly dried up, leaving their workers with no income at all. The Co-operative Society made a grant of £20 to the Somerset Coalfield Distress Fund and increased this in August 1926 by an additional £30 to the Co-operative Union Relief Fund for Societies in Mining Areas.[21] In late May 1926, the parish magazine was able to record: We are grateful that the strike was over and every speaker was able to be present at the World Call to the Church held in Bristol.[22]

But there was no relief for the unemployed: in 1929 There is a lot of unemployment and distress in Box at present .. Donations, large or small, will be welcomed. If you have a comfortable room and plenty of coal, give a thought to those who have, in many cases, only 10s a week Old Age Pension, out of which there has to come rent, fuel and food.[23]

Box Employment Scheme, 1933

The Nightmare of Unemployment which characterised Britain in the 1930s was felt deeply in Box. In August 1932 the parish magazine recorded: The spectre of unemployment is still with us … men out of employment only receive from the State sufficient for bare existence. They soon get despondent, nervy and even reckless.[24] There was some work at times of agricultural activity in the spring plant and autumn harvesting but the vicar wrote: We in Box should be working out some scheme whereby our fellow men might find employment in the year when work is slack. The parish magazine recorded that many villages, especially in Buckinghamshire had set up local initiatives.

Three local men took the local initiative to find work for villagers: RA Legard, AHF Hillier and HE Sykes. They were very different people but with the same cause. Captain Roger Alexander Legard (15 June 1891 - 29 January 1972), was a bachelor who lived at Merrington, Kingsdown who had moved to Box in the early 1930s and quickly became well-known for his work as secretary of the Box British Legion, reading out the Roll of Honour at Remembrance Day Services and organiser of the Poppy Day Collections.[25] In later times he was chairman of the Box Planning Committee, tasked with rebuilding the area after the Second World War, and a representative on the Calne and Chippenham Rural District Council.[26] In the 1930s the register of any employer who could offer work was kept by Roger Legard. Arthur Hulbert Frederick Hillier (1887 – 8 November 1950) was a boot repairer and retailer, who traded in The Parade and later from Dalebrook, Market Place.[27] He was a Methodist and the family were connected to Murray & Baldwin in the Market Place.[28] Arthur’s role was to keep the list of men needing work. Colonel Harry Erling Sykes (born in York in 1872 and died 7 March 1955) was a career soldier serving in the Army Service Corps before the First World War. He later lived at Ashley Cottage and was a founder member of the Comrades Club in the 1920s. He was credited with launching the Box Employment Scheme in May 1933 and he administered the funds.[29] Captain Legard and Colonel Sykes also took an active role in preparations for the Home Guard defence during World War II.[30]

Together these three started the Box Employment Fund in May 1933 as Unemployment is one of the most universal and terrible diseases of modern life. The parish magazine promoted their activities: They felt that if they could only find or make work for 10 men it would be doing some little to help. Their venture of faith has been abundantly justified by results.[31] They planned to put unemployed workers in touch with potential employers and to increase the amount of work available. To do this they needed to be advised of any work and to keep a register of men wanting work and their skills (mostly casual labourers and stone workers). Box organisations raised funds to promote new work with small-scale local events, whist-drives, jumble sales and performances in the Bingham Hall. The aim was to fund institutional work rather than grants to the unemployed. By August 1933, £47 had been raised (although the promoters had targeted £100) and in the summer 4,000 hours of casual work had been supplied in the village.[32] But these measures provided no upturn in the economy.

Conclusion

Unemployment benefit paid to those without work in 1928-30 was reduced in 1931 because of the excessive cost for the national economy. Governments were committed to balancing the national budget and unwilling to contemplate what later became known as “deficit financing” (expenditure finance through state borrowings). The cut was restored in 1934, shortly after the upturn in the economy, which was prompted by low interest rates, the growth of the so-called “new” consumer industries and not least, a massive building boom. The consequence was a remarkable turnaround in living standards. As work returned for military duties so an additional upsurge continued with falling prices after 1935. As sometimes happens in short, sharp recessions, the upturn was equally quick. Box was booming in the late 1930s.

References

[1] Images of Britain's forgotten revolution of 1919, Daily Mail Online

[2] Courtesy Bob Hancock

[3] The Wiltshire Times, 11 January 1919

[4] John Stevenson, British Society 1914-45, 1984, Penguin Books, p.98-101

[5] See Housing and the Workers' Revolution by Sylvia Pankhurst 1918 (marxists.org)

[6] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 September 1921

[7] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 13 June 1901

[8] Salisbury and Wilton Times, 26 July 1901

[9] Parish Magazine, November 1908

[10] Parish Magazine, February 1923

[11] Parish Magazine, February 1924

[12] Parish Magazine, February 1927, June 1927 and March 1929

[13] Parish Magazine, March 1929

[14] Parish Magazine, February, 1930

[15] Parish Magazine, July 1929

[16] Parish Magazine, May 1927

[17] Parish Magazine, October 1933

[18] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 8 May 1926

[19] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 14 August 1926

[20] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Herald, 5 June 1926

[21] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 14 August 1926

[22] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[23] Parish Magazine, March 1929

[24] Parish Magazine, August 1932

[25] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 28 October 1933; North Wilts Herald, 9 April 1937; and Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 23 November 1940 and 12 November 1955

[26] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 14 June 1952

[27] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 27 June 1931

[28] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 January 1938

[29] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[30] The Wiltshire Times, 22 January 1938

[31] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[32] Parish Magazine, July and August 1933

[1] Images of Britain's forgotten revolution of 1919, Daily Mail Online

[2] Courtesy Bob Hancock

[3] The Wiltshire Times, 11 January 1919

[4] John Stevenson, British Society 1914-45, 1984, Penguin Books, p.98-101

[5] See Housing and the Workers' Revolution by Sylvia Pankhurst 1918 (marxists.org)

[6] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 September 1921

[7] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 13 June 1901

[8] Salisbury and Wilton Times, 26 July 1901

[9] Parish Magazine, November 1908

[10] Parish Magazine, February 1923

[11] Parish Magazine, February 1924

[12] Parish Magazine, February 1927, June 1927 and March 1929

[13] Parish Magazine, March 1929

[14] Parish Magazine, February, 1930

[15] Parish Magazine, July 1929

[16] Parish Magazine, May 1927

[17] Parish Magazine, October 1933

[18] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 8 May 1926

[19] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 14 August 1926

[20] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Herald, 5 June 1926

[21] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 14 August 1926

[22] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[23] Parish Magazine, March 1929

[24] Parish Magazine, August 1932

[25] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 28 October 1933; North Wilts Herald, 9 April 1937; and Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 23 November 1940 and 12 November 1955

[26] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 14 June 1952

[27] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 27 June 1931

[28] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 January 1938

[29] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[30] The Wiltshire Times, 22 January 1938

[31] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[32] Parish Magazine, July and August 1933