|

Local Government in Box

Claire Dimond April 2016 The Tudor period saw the development of a totally new system of local government in Box which replaced much of the authority of the old court of the lord of the manor. It saw the introduction of three key positions of authority, the Churchwarden, the Overseer of the Parish and the Justice of the Peace. These positions were held by prominent people in the area who oversaw civil matters such as keeping the peace, upkeep of the roads, helping the poor and in the case of the churchwardens ensuring the upkeep of the church. |

We have records of the actions of these people for Box from 1660 onwards and this article will endeavour to highlight what was happening in Box in this period.

Churchwardens and Ecclesiastical Matters

The first officers of the Box authority were the churchwardens at St Thomas a Becket and St Christopher's Churches. Their control of laity started when they were ordered to keep a register of baptisms, marriages and deaths in the parish in 1538, shortly after Henry VIII's Declaration of Supremacy over the English Church and the breach with Roman Catholicism. The churchwarden's roles were supervised by the local parish vestry.

Vestry meetings were a long established annual gathering of householders in Box churches' vestry rooms (where the priest's vestments were kept). All parish records were kept there, locked in the parish chest secured by three keys.[1] Chaired by the vicar, the vestry meeting delegated duties to two voluntary lay churchwardens appointed annually.

The first officers of the Box authority were the churchwardens at St Thomas a Becket and St Christopher's Churches. Their control of laity started when they were ordered to keep a register of baptisms, marriages and deaths in the parish in 1538, shortly after Henry VIII's Declaration of Supremacy over the English Church and the breach with Roman Catholicism. The churchwarden's roles were supervised by the local parish vestry.

Vestry meetings were a long established annual gathering of householders in Box churches' vestry rooms (where the priest's vestments were kept). All parish records were kept there, locked in the parish chest secured by three keys.[1] Chaired by the vicar, the vestry meeting delegated duties to two voluntary lay churchwardens appointed annually.

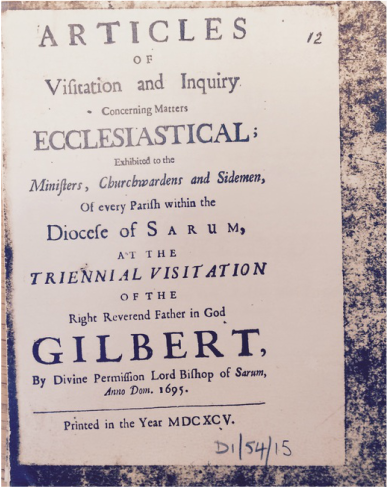

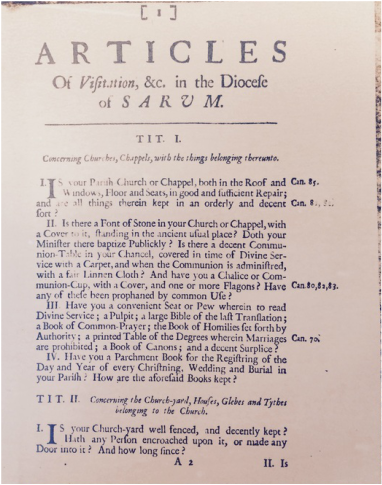

Above: Extracts from the Churchwardens' Handbook (courtesy Wiltshire History Centre)

The churchwardens received the church income from pew rents (enclosed bench seats reserved for important individuals) and maintained the fabric of the church and the assets of the church. Churchwardens were given a book entitled, Articles of visitation and enquiry concerning matters ecclesiastical exhibited to churchwardens which detailed the areas of church life that were under their control. It took a form of a series of questions such as

Is your parish church both in the roof and windows, floor and seats in good and sufficient repair?

Does your minister read with an audible and distinct voice?

Doth every parishioner demean himself reverently in your church during divine service?

Are there any living within your parish as man and wife who are within degrees prohibited?

Is your parish church both in the roof and windows, floor and seats in good and sufficient repair?

Does your minister read with an audible and distinct voice?

Doth every parishioner demean himself reverently in your church during divine service?

Are there any living within your parish as man and wife who are within degrees prohibited?

|

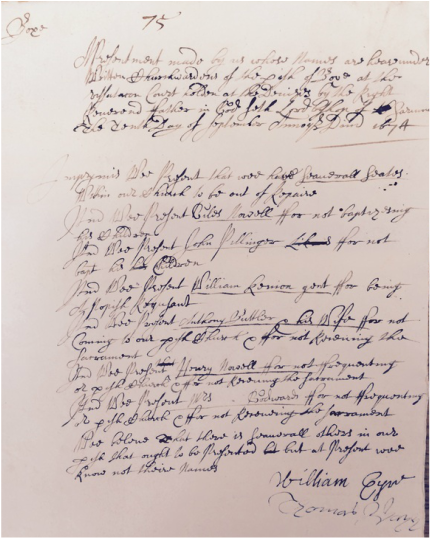

Any ecclesiastic problems were then reported to archdeacons who made six-monthly visits to the village. The first record of the churchwarden presentiments is from 1674 in which the churchwardens, William Eyre and Thomas Bayley, report that Giles Nowell and John Pilinger had not baptised their children.

Henry Nowell (father of Giles), Anthony Butler and his wife and Mrs Goodward had not been coming to church or receiving the sacrament. Sir William Kenyon, gent, was a recusant as were several others in the parish but they don’t have names. Several pews needed repair. There is no record of what punishment was awarded to those named in the presentiment but we can assume there was some sort of reprisal as Giles Nowell started to baptise his children from 1677. However the 1683 presentiments show Henry Nowell was still refusing to go to church. Is this an example of non-conformity in the village or were those named simply not bothered about going to church? |

The 1689 Act of Toleration, which came too late for Henry who died in 1684, meant that people could worship in their own church and the churchwarden presentiments become rather dull from this date onwards with most parishes having nothing to report.

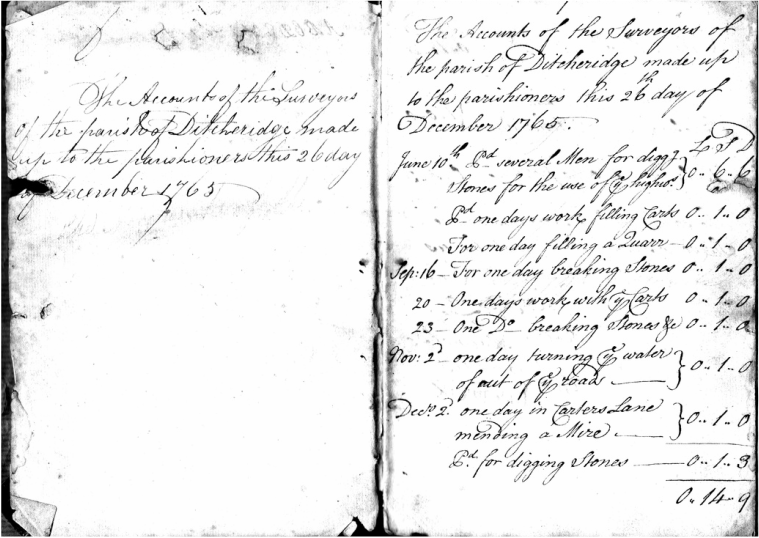

Increasingly new responsibilities were given to the vestry to nominate other parish officers: a Surveyor of the Highway was appointed after 1555 to maintain the condition of roads and bridges; two Overseers of the Poor were appointed after 1563 to set and collect rates from householders for distribution to the needy in the parish; the Tithingman (village constable) was originally a manorial position which was transferred to the vestry and whose duty was to maintain local law and order; and the vestry clerk.

Parish vestry meetings were called once a month, usually on a Sunday, at which each of the officials submitted a report. The first meetings were held in the Church, but later they moved to the Bear. The meeting was open to all parishioners and a bell was tolled to announce its commencement.[2] Officials sometimes served on the several committees, often on a rota basis, appointed yearly at an annual vestry meeting.

It was the local gentry who ratified the vestry appointments in their role as Justices of the Peace for Box at Chippenham. The JPs were also responsible for quelling public disorder and everyday local law and order.

Parish vestry meetings were called once a month, usually on a Sunday, at which each of the officials submitted a report. The first meetings were held in the Church, but later they moved to the Bear. The meeting was open to all parishioners and a bell was tolled to announce its commencement.[2] Officials sometimes served on the several committees, often on a rota basis, appointed yearly at an annual vestry meeting.

It was the local gentry who ratified the vestry appointments in their role as Justices of the Peace for Box at Chippenham. The JPs were also responsible for quelling public disorder and everyday local law and order.

|

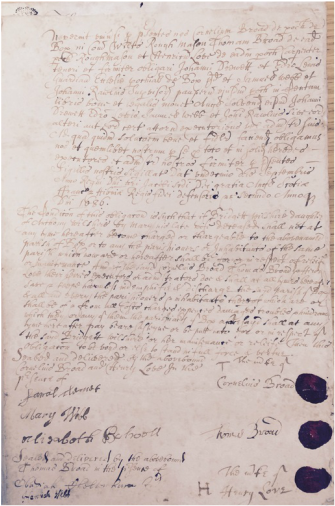

Overseers of the Poor

Care for the disadvantaged had been set out in the Poor Law Act of 1601. It was a decisive contribution to local society, truly astonishing in its scope and detail. The Act was based on values of mutual self-help delivered by the Overseers of the Poor to offer support for the poor and the elderly. The Act enabled the Overseers to collect the Poor Rate which was a tax levied on property values, in Box sometimes two or three rates of 3d in £1 being levied in a single year, and distribute the money to the poor of the parish.[3] We have records from 1660 which detail the powers the Overseers had, these included caring for the harmless poor, mostly orphaned children; deciding who can move into the village and issuing removal orders to those they do not want; dealing with bastardy cases including issuing arrest warrants to alleged fathers. Pauper children were protected by bonds to save parish harmless. These were signed obligation between the parishioners of Box and the overseers of the poor to pay any charges incurred by the parish harmless. Right: Indenture for the support of the Broad children (courtesy Wiltshire History Centre). |

Support for |

Cornelius Broad, Thomas Broad (both rough-masons in Box) and Henry Love (Carpenter in Box) agree to pay charges for Bridgett, daughter of Anthony Wilshire by his late wife Mary of Ditteridge in 1686. Bridgett was born in 1682, her mother died two years later and her father in 1688. We do not know what relationship the child had to those who paid for her.

|

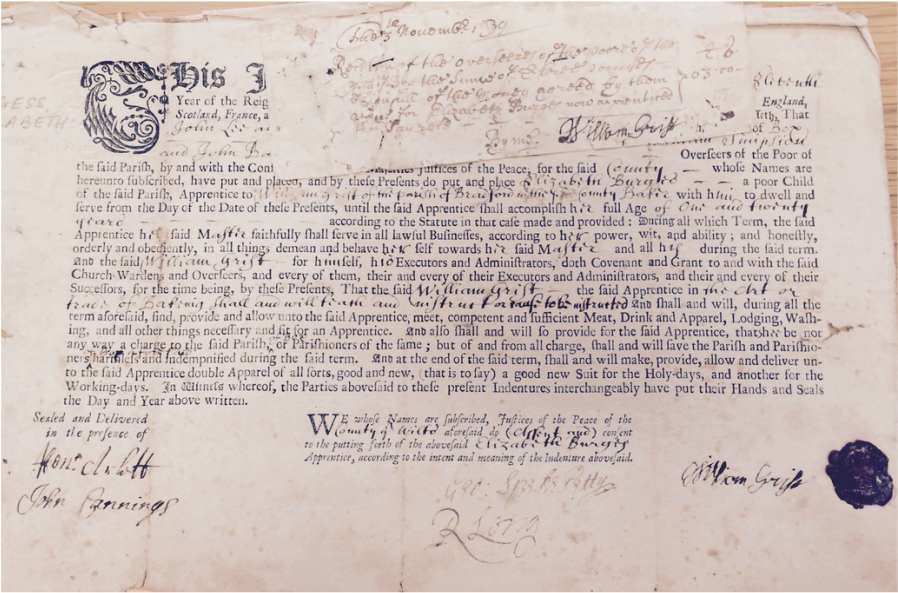

Once they reached the age of eight the parish overseers could arrange apprenticeships for pauper children. Two churchwardens and two overseers of the poor, witnessed by two JPs, were authorised to make an indenture between the child of the parish and a master who they would serve until they are one and twenty. The Master often had to make a down payment to the parish and had to satisfy various other responsibilities. They must provide meat, drink, apparel (including a good new suit for the holy days), lodging, washing and all things necessary and fit for an apprentice. In addition they must ensure the apprentice does not become a charge to the parish.

Examples |

Ann Rawlings in 1680, a poor motherless child, is apprenticed to Mary Ralings wife of John in the art and skill of housewifery.

Elizabeth Burgess on 4 Nov 1699 apprenticed to William Grist, a baker in Bradford-on-Avon. William paid £3 to the parish for her. |

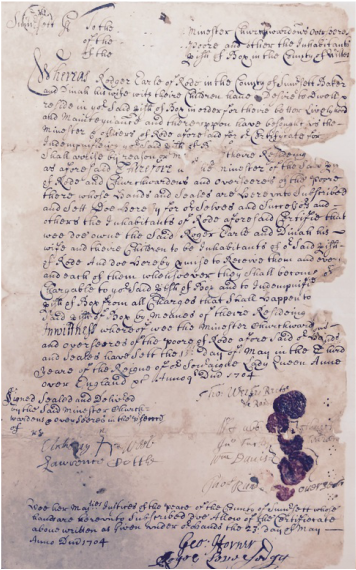

People Wanting to Move Parish

People needed to move parish for many ordinary reasons including work, marriage and to support family members. Permission had to be obtained for coming to Box.

People needed to move parish for many ordinary reasons including work, marriage and to support family members. Permission had to be obtained for coming to Box.

Asking |

Roger Earle, with his wife and child in 1701, a baker from Rode, Somerset. They wanted to move to Box for convenience of trade, and for better livelihood and maintenance. The Parish Overseers and Churchwardens of Rode agreed that they would support him if it went wrong and it did, Box Parish Overseers sent them back to Rode in 1704 !

|

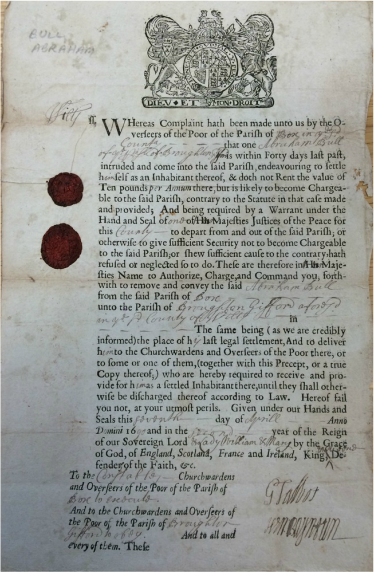

Removal orders were quite common as The 1662 Act of Settlement had empowered justices to eject as vagrants any newcomers who had no means of self-support.

Concern over |

Abraham Bull of Broughton Gifford within forty days last past intruded and came into the said parish (Box) endeavouring to settle himself as an inhabitant and doth not rent the value of ten pounds per annum there, but is likely to become chargeable to the said parish, 1690.

|

Above left: Earle's Indenture to come to Box, and above right: Bull's removal order (both courtesy Wiltshire History Centre).

Sometimes parishes contested decisions to send people back to their parish of origin.

Returning |

In 1677, Box parish tried to send William Wilshire (relative of Anthony?) back to Bradford-on-Avon, his designated settlement but the Bradford-on-Avon parish officers contested the decision and the case was sent to the Quarter Sessions who decided in Box’s favour and poor William was sent back.

In March 1669, Walter Palmer was removed from Box to Colerne, but because of his previous disobedience he was first taken to the house of correction at Devizes where he is to be punished as a Vagabond (whipped).[4] |

Pregnant mothers could ask the parish for money and support on behalf of their illegitimate children.

|

In 1717, Dinah Robson had a bastard female child named Sarah, father reputed to be Charles Abbott junior. The Parish Overseers forced Charles to come to the Church House on Sunday to pay 4 shillings a month starting on 2 March until the child was eight and could be apprenticed. The document has no full date so we don't know whether this was before Charles Abbott married Hannah Pillinger on 8 July 1717. The Parish Overseers also tried to remove Dinah in October 1717 claiming she was from Bradford-on-Avon, not Box. When she wouldn't leave, Dinah baptised Sarah twice on 26 Dec 1717, as Sarah Robson and Sarah Abbott, as she saith, so we know she didn't go, and the Overseers decided to force Charles to pay up.

|

Justices of the Peace

In direct control of the system were the county Justices of the Peace who dealt with legal matters, and administer verdicts through courts of law called Quarter Sessions. The courts of Quarter Sessions were among the great events of the provincial calendar.[5] They were attended by 2 or more Justices, the Clerk of the Peace, the High Constable, 4 attorneys, 5 ordinary clerks and the juries, bailiffs, sheriffs and petty constables.

Sitting for two or three days four times a year, at Epiphany in January, Easter, Midsummer and Michaelmas in September, the Justices had enormous power in local affairs. Often they delegated their duties down to divisional districts run by the Clerk of the Peace. They administered fines, whippings and brandings; determined judgment for vagrants, poachers and parents of illegitimate children; maintained the regulation of trade and control of ale-houses.

The records of the Quarter Sessions for Wiltshire exist but are incredibly difficult to handle. The Quarter Sessions for the period 1642-1654 have been transcribed and Box is mentioned twice. In 1649 at the Sessions in Warminster, Nicholas Spence informed the court that he had disbursed to the parish, who were infected with the contagious disease of the plague, the sum of 46 shillings which the parish utterly refuses to make satisfaction (actually pay). The court ordered inhabitants of Box to make an equal and indifferent rate for the paying of Spencer. On 4 October 1653 in Marlborough, William Cottle of Box was committed to the house of correction at Devizes for selling ale without a licence: If he enters into a recognisance with sufficient sureties (such as William Eyres, JP shall approve of) never to sell ale without a licence he shall be discharged forthwith.

In direct control of the system were the county Justices of the Peace who dealt with legal matters, and administer verdicts through courts of law called Quarter Sessions. The courts of Quarter Sessions were among the great events of the provincial calendar.[5] They were attended by 2 or more Justices, the Clerk of the Peace, the High Constable, 4 attorneys, 5 ordinary clerks and the juries, bailiffs, sheriffs and petty constables.

Sitting for two or three days four times a year, at Epiphany in January, Easter, Midsummer and Michaelmas in September, the Justices had enormous power in local affairs. Often they delegated their duties down to divisional districts run by the Clerk of the Peace. They administered fines, whippings and brandings; determined judgment for vagrants, poachers and parents of illegitimate children; maintained the regulation of trade and control of ale-houses.

The records of the Quarter Sessions for Wiltshire exist but are incredibly difficult to handle. The Quarter Sessions for the period 1642-1654 have been transcribed and Box is mentioned twice. In 1649 at the Sessions in Warminster, Nicholas Spence informed the court that he had disbursed to the parish, who were infected with the contagious disease of the plague, the sum of 46 shillings which the parish utterly refuses to make satisfaction (actually pay). The court ordered inhabitants of Box to make an equal and indifferent rate for the paying of Spencer. On 4 October 1653 in Marlborough, William Cottle of Box was committed to the house of correction at Devizes for selling ale without a licence: If he enters into a recognisance with sufficient sureties (such as William Eyres, JP shall approve of) never to sell ale without a licence he shall be discharged forthwith.

Box Poorhouse Built 1727

The Poorhouse (now called Springfield House) is one of the crowning glories of the village.[6] The three-story development was a bold and costly venture, a symbol of a self-supporting community. It is not unique, Corsham converted four cottages for its poorhouse in 1728, but the scale and grandeur of Springfield House is still impressive today. The house was built in response to an Act of Parliament of 1722 encouraging parishes to rent or own a workhouse for the poor. For a century, the poor had been encouraged to work at home through the issue of materials (such as flax, hemp, wool, thread and iron) with which they could produce goods to be sold for their maintenance. Henceforth this relief was to be limited to those people actually lodging in the institution.

The Poorhouse was begun in 1727 for the people of Box and Ditteridge for the reception and maintenance of our poor.[7] The initial impetus came from the Rev George Miller, who planned to build on wasteland next to the schoolmaster’s house, aided by donations from the widow of Henry Hoare. The bulk of the money, however, came from the rates, and put considerable strain on local resources, particularly after earlier calls for the school and the church. In October 1728 a poor rate of £50 and a loan of £200 was agreed. The Vestry minutes reported, The burden of the poor (rate) had increased very much, the more for the want of the benefit of the workhouse, begun but not yet finished. Later an additional rate of 1d in £1 was set for the next 38 months to raise funds of £252.7s.8d to enable the Poorhouse to be completed before Easter 1729.

When the Poorhouse opened in 1729, it was a marvel of care. It included a workroom, kitchen, brew-house, washhouse, and a separate room for the Master.[8] The workroom was primarily devoted to cloth-making and included 12 spinning wheels, two looms and two scribbling horses for combing the wool. Two hour-glasses were included in the workroom to ensure the inmates worked their full time. The kitchen prepared its own food with a meat block and cleaver, two saltboxes for keeping the food, and the usual kitchen utensils including a rowling pin. Malt beer was made in the brew-house with the meshing tub and stick.

On its opening, there were 17 female and 12 male occupants. Men and women were issued with a standard amount of clothing. For men, this included shoes with buckles made on the premises, an apron for working and a biggin (night-cap). For females there was also a handkerchief and comb, and two blankets. Recreation facilities comprised The Bible, The Whole Duty of Man, two Common Prayer Books and two New Testaments.

The Poorhouse (now called Springfield House) is one of the crowning glories of the village.[6] The three-story development was a bold and costly venture, a symbol of a self-supporting community. It is not unique, Corsham converted four cottages for its poorhouse in 1728, but the scale and grandeur of Springfield House is still impressive today. The house was built in response to an Act of Parliament of 1722 encouraging parishes to rent or own a workhouse for the poor. For a century, the poor had been encouraged to work at home through the issue of materials (such as flax, hemp, wool, thread and iron) with which they could produce goods to be sold for their maintenance. Henceforth this relief was to be limited to those people actually lodging in the institution.

The Poorhouse was begun in 1727 for the people of Box and Ditteridge for the reception and maintenance of our poor.[7] The initial impetus came from the Rev George Miller, who planned to build on wasteland next to the schoolmaster’s house, aided by donations from the widow of Henry Hoare. The bulk of the money, however, came from the rates, and put considerable strain on local resources, particularly after earlier calls for the school and the church. In October 1728 a poor rate of £50 and a loan of £200 was agreed. The Vestry minutes reported, The burden of the poor (rate) had increased very much, the more for the want of the benefit of the workhouse, begun but not yet finished. Later an additional rate of 1d in £1 was set for the next 38 months to raise funds of £252.7s.8d to enable the Poorhouse to be completed before Easter 1729.

When the Poorhouse opened in 1729, it was a marvel of care. It included a workroom, kitchen, brew-house, washhouse, and a separate room for the Master.[8] The workroom was primarily devoted to cloth-making and included 12 spinning wheels, two looms and two scribbling horses for combing the wool. Two hour-glasses were included in the workroom to ensure the inmates worked their full time. The kitchen prepared its own food with a meat block and cleaver, two saltboxes for keeping the food, and the usual kitchen utensils including a rowling pin. Malt beer was made in the brew-house with the meshing tub and stick.

On its opening, there were 17 female and 12 male occupants. Men and women were issued with a standard amount of clothing. For men, this included shoes with buckles made on the premises, an apron for working and a biggin (night-cap). For females there was also a handkerchief and comb, and two blankets. Recreation facilities comprised The Bible, The Whole Duty of Man, two Common Prayer Books and two New Testaments.

Conclusion

The Elizabethan Poor Law was a remarkable welfare system which also encouraged a redistribution of wealth unprecedented in the contemporary western world. It was even more notable because of the social and moral responsibility it put upon neighbours to pay for and administer the system. In our modern materialistic world it seems an impossible concept yet it lasted for two hundred years from 1601 until the amalgamation of parish relief into the unions after 1834.

Before the existence of the laws, local authority had been administered by the lord of the manor often in ways which were arbitrary and preferential. After 1834 the control of the state has become all-encompassing, expected to provide nationally for the disadvantaged and elderly in our society. And we have almost entirely lost the concept of local self-determination.

The Elizabethan Poor Law was a remarkable welfare system which also encouraged a redistribution of wealth unprecedented in the contemporary western world. It was even more notable because of the social and moral responsibility it put upon neighbours to pay for and administer the system. In our modern materialistic world it seems an impossible concept yet it lasted for two hundred years from 1601 until the amalgamation of parish relief into the unions after 1834.

Before the existence of the laws, local authority had been administered by the lord of the manor often in ways which were arbitrary and preferential. After 1834 the control of the state has become all-encompassing, expected to provide nationally for the disadvantaged and elderly in our society. And we have almost entirely lost the concept of local self-determination.

References

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.22

[2] This section is indebted to Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.44 onwards

[3] Andrew Langley and John Utting, The Village on the Hill, Colerne History Group, 1990, p.103

[4] Andrew Langley and John Utting, The Village on the Hill, p.115

[5] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 4, Introduction

[6] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.86 on

[7] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.84

[8] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.86

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, 1985, The Downland Press, p.22

[2] This section is indebted to Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.44 onwards

[3] Andrew Langley and John Utting, The Village on the Hill, Colerne History Group, 1990, p.103

[4] Andrew Langley and John Utting, The Village on the Hill, p.115

[5] Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 4, Introduction

[6] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.86 on

[7] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.84

[8] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire - An Intimate History, p.86