Georgian Middlehill and the Tree of Life Alan Payne January 2019

In the Georgian period we can see how a residential hamlet developed at Middlehill. Francis Allen's 1626 map shows that some properties existed above Middlehill Common but these were humble buildings set in plots of land called messuages rather than important houses. They were intended for owners to have a few animals to keep for food, a garden for vegetables and a few fruit trees.

Interestingly, Middlehill was defined by the amount of spring water in the area, as indicated by the Tree of Life drawn in the middle of the map area. The tree often indicated a sacred place whereby knowledge was passed from heaven to earth. Sometimes it has been taken as the rood (cross) on which Christ was crucified. We don't know why Allen depicted the tree in Middlehill but we might imagine there was a popular local myth.

Interestingly, Middlehill was defined by the amount of spring water in the area, as indicated by the Tree of Life drawn in the middle of the map area. The tree often indicated a sacred place whereby knowledge was passed from heaven to earth. Sometimes it has been taken as the rood (cross) on which Christ was crucified. We don't know why Allen depicted the tree in Middlehill but we might imagine there was a popular local myth.

Middlehill House

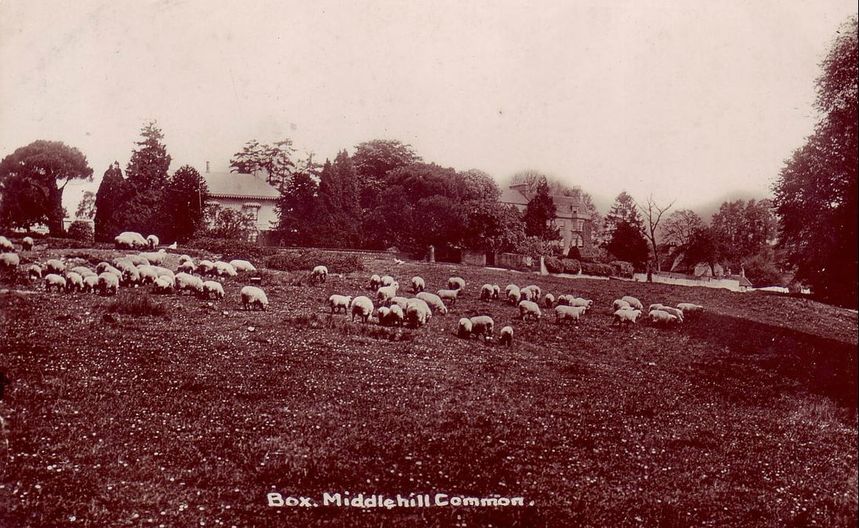

The messuages shown on Allen's map are mostly held by the Head family (John Hedd (sic) Senior and A Hedd). The land appears to have been enclosed off Middlehill Common, land open to the public for grazing their animals as shown by the red dots on the map. The family died out and a century later the land appears to have been owned by William Lewis and occupied (rented) by the Clements family of Ditteridge. Catherine, the daughter of William Clements the younger, married Samuel Ricketts, a leather draper of Box, and they granted Arthur Lewis, leather draper, a lease in Middlehill close of meadow or pasture and woody ground (and) hereditaments in a contract dated 8 February 1731 for the sum of £50. There is no mention of the springs, apart from the watercourses which went with the property.

The messuages shown on Allen's map are mostly held by the Head family (John Hedd (sic) Senior and A Hedd). The land appears to have been enclosed off Middlehill Common, land open to the public for grazing their animals as shown by the red dots on the map. The family died out and a century later the land appears to have been owned by William Lewis and occupied (rented) by the Clements family of Ditteridge. Catherine, the daughter of William Clements the younger, married Samuel Ricketts, a leather draper of Box, and they granted Arthur Lewis, leather draper, a lease in Middlehill close of meadow or pasture and woody ground (and) hereditaments in a contract dated 8 February 1731 for the sum of £50. There is no mention of the springs, apart from the watercourses which went with the property.

Shortly thereafter the land came into the possession of John Neate, a wealthy Bristol merchant who lived in Cheney Court in 1769 probably rented from the Northey family. One branch of the family were Quakers with considerable dealings in Philadelphia. John probably wasn't a Quaker and he owned black slaves at Cheney Court. In 1775 one of them, John Camery, run away from his service and Neate put out a reward of 10s.6d for his recapture.[1] Described as of dark complexion, about thirty years of age, stoops in his walk, John Camery had been always bred up in the husbandry business, a farm worker.

As an investment John Neate built a substantial house at Middlehill, advertised in 1769 as a new-built house, four rooms on a floor (sic), with stable, coach house and garden ... and about four acres of good pasture ground.[2] The advert wasn't strictly accurate and a correction was made later that month that A coach house will be built if desired.[3] John Neate died in 1808, by which time he was living in Middlehill House, now extended and described as large convenient house, with every requisite office.[4] His heir George Neate of Warminster put the property up for rent describing it as, Genteel Country Residence. This house is roomy and replete with every convenience ... The situation is delightful, possessing a picturesque view ... stage-coaches and other public carriages are almost constantly passing to and from Bath.[5] This wasn't the property we see at present because the Regency-style front of the house dates from 1830-40.[6]

As an investment John Neate built a substantial house at Middlehill, advertised in 1769 as a new-built house, four rooms on a floor (sic), with stable, coach house and garden ... and about four acres of good pasture ground.[2] The advert wasn't strictly accurate and a correction was made later that month that A coach house will be built if desired.[3] John Neate died in 1808, by which time he was living in Middlehill House, now extended and described as large convenient house, with every requisite office.[4] His heir George Neate of Warminster put the property up for rent describing it as, Genteel Country Residence. This house is roomy and replete with every convenience ... The situation is delightful, possessing a picturesque view ... stage-coaches and other public carriages are almost constantly passing to and from Bath.[5] This wasn't the property we see at present because the Regency-style front of the house dates from 1830-40.[6]

|

Spa House

In between the building and rebuilding of Middlehill House, the rest of the hamlet was developed based on the springs in the area on land bought from Middlehill House.[7] The spa achieved a degree of recognition. A newspaper advertisement of 1788 (two years after Spa House was built) described a property owned by William Clement of Ditteridge and located it as two furlongs from Middlehill Spaw (sic) ... There is a fine spring of soft water near the premises.[8] The spa was developed at Spa House, Middlehill where visitors could take the waters and wash in the curative, medicinal spring. Box was not the only local development. Over 31 places in Wiltshire had mineral wells, and spas were developed at Holt (1713), Melksham (1813) and Purton Stoke (1859).[9] Middlehill Spa was promoted by Dr William Falconer of Bath, who entered into a plan with another individual (Mr West) a baker, who lives at Middle-Hill, near Box ... for erecting a lodging and boarding-house, pump-room, and other buildings, suitable for the reception of company, and the accommodation of invalids.[10] In 1786 Falconer wrote a learned paper praising Box waters for their astounding curative properties.[11] |

The water was salty to taste with a sulphurous smell: Though unpleasant at first, the palate is soon reconciled to it. It was a gentle laxative, and a cure for foul eruptions of the skin, worms, acidity of the stomach. John Britton wrote about the springs: At a place called Middle Hill ... are two mineral springs, one of which contains iron and neutral salts and forms a mild aperoent chalbeate; the other is impregnated with the hydro-sulphuric and carbonic gases, possessing some efficacy as an alternative. [12] By 1789 the water was being bottled and sold at Mr Grime’s shop, Broad Street, Bath.[13]

Spa House was purpose-built (on part of the land belonging to an earlier property at Middlehill House). The house has three stories and an attic and a large, splendid window in the front, which served to give a view when the room was being used for the formal receptions.[14] This is referred to in 1793 as Assemble or Tea-Room, 39 feet long.[15] The house had: standing for four carriages, stabling for 9 horses, with lodging rooms over the same. It had a pump room (to ensure the water supply never ran dry) and another separate boarding house. Spa Cottage is possibly the old pump house and it also dates from the late 1700s.[16]

The coach house belonging to the cottage may have been for the travelling needs of visitors to the Spa but there is some evidence that it is a later addition.

A second boarding house was built, Longridge House, which was originally listed as: House adjoining Spa House. It is similar in style and the two properties are closely adjoining. The spa had some initial success and West cashed in by selling the property at auction in 1793.[17] With the advent of the war against France in 1793, however, its success was curtailed. The venture as a spa had closed by 1814 and Britton reported that the buildings thus raised at an immense expense are now let as lodgings to such persons as are disposed to retire economically from Bath during the summer season.[18] An advertisement for the sale of Prospect House in the same year advertised it as within a mile of the pleasant village of Box and Middlehill Spa.[19] It was the end of the venture and by 1827 Spa House and Longridge House were both put up for sale.[20]

Spa House was purpose-built (on part of the land belonging to an earlier property at Middlehill House). The house has three stories and an attic and a large, splendid window in the front, which served to give a view when the room was being used for the formal receptions.[14] This is referred to in 1793 as Assemble or Tea-Room, 39 feet long.[15] The house had: standing for four carriages, stabling for 9 horses, with lodging rooms over the same. It had a pump room (to ensure the water supply never ran dry) and another separate boarding house. Spa Cottage is possibly the old pump house and it also dates from the late 1700s.[16]

The coach house belonging to the cottage may have been for the travelling needs of visitors to the Spa but there is some evidence that it is a later addition.

A second boarding house was built, Longridge House, which was originally listed as: House adjoining Spa House. It is similar in style and the two properties are closely adjoining. The spa had some initial success and West cashed in by selling the property at auction in 1793.[17] With the advent of the war against France in 1793, however, its success was curtailed. The venture as a spa had closed by 1814 and Britton reported that the buildings thus raised at an immense expense are now let as lodgings to such persons as are disposed to retire economically from Bath during the summer season.[18] An advertisement for the sale of Prospect House in the same year advertised it as within a mile of the pleasant village of Box and Middlehill Spa.[19] It was the end of the venture and by 1827 Spa House and Longridge House were both put up for sale.[20]

Conclusion

Was the building of a spa at Box merely a scam? Clearly it was an enormously expensive development and it appears to have been well-appointed for genteel residents. It isn’t the property that has caused some to doubt the merit of the project but rather that the water itself had little or no medicinal properties. The growth of cities in Georgian England put pressure on the cleanliness of water supply with raw sewage, domestic rubbish and industrial effluent being frequently deposited into the drinking water supply. Little wonder that many people turned to ale and the notorious gin as their preferred source of liquid. There is no doubt that the spring water of Middlehill was substantially better than most of the water drunk in the city of Bath.

Considering its role as a lifeforce for everyone, it is curious that the regulation of the water industry was instituted so late in England. In 1945 there were 1,000 bodies involved in the supply of water and 1,400 in the disposal of effluent. Most of these were local authorities who obviously depended on the amount of local rates to raise standards.

Was the building of a spa at Box merely a scam? Clearly it was an enormously expensive development and it appears to have been well-appointed for genteel residents. It isn’t the property that has caused some to doubt the merit of the project but rather that the water itself had little or no medicinal properties. The growth of cities in Georgian England put pressure on the cleanliness of water supply with raw sewage, domestic rubbish and industrial effluent being frequently deposited into the drinking water supply. Little wonder that many people turned to ale and the notorious gin as their preferred source of liquid. There is no doubt that the spring water of Middlehill was substantially better than most of the water drunk in the city of Bath.

Considering its role as a lifeforce for everyone, it is curious that the regulation of the water industry was instituted so late in England. In 1945 there were 1,000 bodies involved in the supply of water and 1,400 in the disposal of effluent. Most of these were local authorities who obviously depended on the amount of local rates to raise standards.

References

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 27 July 1775

[2] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 8 June 1769

[3] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 29 June 1769

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 17 March 1808

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 9 June 1808

[6] Historic Buildings

[7] PM Slocombe Notes in County Library, WRO

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 6 July 1788

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, pages 386-8

[10] John Britton, Beauties of Wiltshire, 1825, p.139

[11] Dr William Falconer, A Brief Account of the Qualities of the Newly Discovered Mineral Waters of Middle-Hill, 1876, Wiltshire History Centre

[12] John Britton, Topographical Sketches of North Wiltshire, 1826

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1789

[14] Historic Buildings, p.105

[15] The Bath Chronicle 9th May 1793

[16] Historic Buildings, p.106

[17] The Bath Chronicle 9th May 1793

[18] John Britton, A Topographical and Historical Description of the County of Wilts, p.502

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 10 March 1814

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 26 July 1827

[1] The Bath Chronicle, 27 July 1775

[2] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 8 June 1769

[3] Bath and Bristol Chronicle, 29 June 1769

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 17 March 1808

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 9 June 1808

[6] Historic Buildings

[7] PM Slocombe Notes in County Library, WRO

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 6 July 1788

[9] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, pages 386-8

[10] John Britton, Beauties of Wiltshire, 1825, p.139

[11] Dr William Falconer, A Brief Account of the Qualities of the Newly Discovered Mineral Waters of Middle-Hill, 1876, Wiltshire History Centre

[12] John Britton, Topographical Sketches of North Wiltshire, 1826

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 9 July 1789

[14] Historic Buildings, p.105

[15] The Bath Chronicle 9th May 1793

[16] Historic Buildings, p.106

[17] The Bath Chronicle 9th May 1793

[18] John Britton, A Topographical and Historical Description of the County of Wilts, p.502

[19] The Bath Chronicle, 10 March 1814

[20] The Bath Chronicle, 26 July 1827