Tragic Death of Walter Macdonald Currant John Currant, September 2022

Walter Macdonald Currant (nicknamed Mackie) was the nineth of eleven children of Edward George Currant and Ella Louise Norris of Wilton Cottages, Ashley. Edward George was employed by the Great Western Railway Company (GWR), starting as a packer, maintaining the ballast under the railway track, and later as a platelayer, maintaining the rails. The GWR had been a model employer offered a regular pay, training and a pension but it was beset by problems in the 1920s and 30s. But the

General Strike of 1926 reflected the problems that the company experienced through the depression, competition from road transport and railway redundancies.

There was little wonder that Mackie didn’t find a stable job and joined the army as a private seeking adventure. On 18 November 1939, he married Mildred Tugwell and he re-joined the Worcester Regiment as part of the British Expeditionary Force in France shortly afterwards. The family celebrated the marriage with a write-up in the local newspaper. The bridesmaids were Misses P and M Currant, who wore mauve taffeta dresses with veils and shoes to tone (match), silver shoes and carried bouquets of mauve chrysanthemums.[1] Arthur George Currant was the best man.

General Strike of 1926 reflected the problems that the company experienced through the depression, competition from road transport and railway redundancies.

There was little wonder that Mackie didn’t find a stable job and joined the army as a private seeking adventure. On 18 November 1939, he married Mildred Tugwell and he re-joined the Worcester Regiment as part of the British Expeditionary Force in France shortly afterwards. The family celebrated the marriage with a write-up in the local newspaper. The bridesmaids were Misses P and M Currant, who wore mauve taffeta dresses with veils and shoes to tone (match), silver shoes and carried bouquets of mauve chrysanthemums.[1] Arthur George Currant was the best man.

|

Mackie’s Death, 1940

Mackie became the first of eighteen Box fatalities in the Second World War. He was reported missing in the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation and there was no news of him for nine weeks. The Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald of 20 July 1940 (with photo seen left) carried a report: Private Currant was called up under Militia Act and had been serving in the Army for a year. He was 21 years of age and just before last Christmas was married to Miss M Tugwell of Englishcombe Lane, Bath.[2] The paper asked for any information about his whereabouts, particularly targetting families of other missing soldiers who might have been captured. By November it became apparent that he had died in May 1940 a few miles south of Dunkirk fighting with the Worcestershire Regiment. |

Rumours about Mackie’s death alarmed the family, even though they did not have full details. After the war no-one spoke of the way he died, nor of his marriage, as if they didn’t wish to learn more information about the tragedy. Amazingly, Mackie’s death took a strange twist decades later with a letter from Jack Squire of the Dunkirk Veterans Association to Effie Anderson, Mackie's elderly sister wanting to know more.

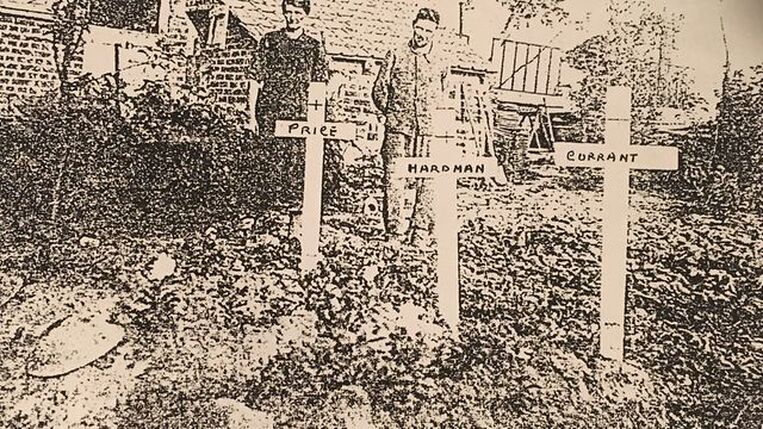

Mackie had been executed with ten comrades at the farm of M and Mme Vandamme in Rexpoede. The farmer had buried the bodies in their garden until the Germans later reinterred the remains. Mackie’s grave had been honoured by the French authorities since then, for giving his life for his country, for France, for liberty and peace and he was very courageous to the end.[3] Mr and Mme Vandamme, recounted the story that the British soldiers had been badly wounded a few hours earlier and were hiding in a rabbit shed at the farm as the Germans closed in on Dunkirk. The farmer and his wife gave them food and dressed their wounds but they were discovered by a German patrol. The Germans disarmed the soldiers but they didn't want prisoners and shot them in cold blood. In appreciation for their bravery the farmer's family and the local mayor had laid flowers on the graves every year afterwards.

Mackie had been executed with ten comrades at the farm of M and Mme Vandamme in Rexpoede. The farmer had buried the bodies in their garden until the Germans later reinterred the remains. Mackie’s grave had been honoured by the French authorities since then, for giving his life for his country, for France, for liberty and peace and he was very courageous to the end.[3] Mr and Mme Vandamme, recounted the story that the British soldiers had been badly wounded a few hours earlier and were hiding in a rabbit shed at the farm as the Germans closed in on Dunkirk. The farmer and his wife gave them food and dressed their wounds but they were discovered by a German patrol. The Germans disarmed the soldiers but they didn't want prisoners and shot them in cold blood. In appreciation for their bravery the farmer's family and the local mayor had laid flowers on the graves every year afterwards.

Mackie was reburied at the Rexpoede Communal Cemetery in July 1941, his grave tended by the farmer until it was taken over by the War Graves Commission after 1945. It is one of just 33 servicemen buried there, of which 11 have never been identified. Mildred married again in 1941 to William Yuille.

Geneva Convention, 1949

Mackie’s death was just one example of the ill-treatment of prisoners that occurred in World War II, both in Europe and the Far East. The third Geneva Convention of 1949 confirmed the rights of prisoners of war that they should not be subjected to punishment but merely deprived of liberty to stop their re-entry into the hostilities and released as soon as possible at the cessation of war. They were to be protected against any act of violence, as well as against intimidation, insults, and public curiosity and there were provisions for the standard of accommodation, food, clothing, hygiene and medical care.[4]

The 1949 legislation was partly a reinforcement of the 1929 protocols, which had been largely ignored in the Second World War. But there were significant additions with the law applying to volunteer corps and resistance fighters and the ruling that prisoners were the responsibility of the state, not the captors, allowing prosecution of political leaders for war crimes, not just the ordinary soldiers following orders.

Mackie’s death was just one example of the ill-treatment of prisoners that occurred in World War II, both in Europe and the Far East. The third Geneva Convention of 1949 confirmed the rights of prisoners of war that they should not be subjected to punishment but merely deprived of liberty to stop their re-entry into the hostilities and released as soon as possible at the cessation of war. They were to be protected against any act of violence, as well as against intimidation, insults, and public curiosity and there were provisions for the standard of accommodation, food, clothing, hygiene and medical care.[4]

The 1949 legislation was partly a reinforcement of the 1929 protocols, which had been largely ignored in the Second World War. But there were significant additions with the law applying to volunteer corps and resistance fighters and the ruling that prisoners were the responsibility of the state, not the captors, allowing prosecution of political leaders for war crimes, not just the ordinary soldiers following orders.

War grave of Mackie Currant at Rexpoede Communal Cemetery (courtesy John Currant)

References

[1] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 25 November 1939

[2] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 July 1940

[3] April Roach, https://www.romfordrecorder.co.uk/news/harold-wood-woman-shares-remembrance-day-story-1-6358280

[4] Prisoners of war and detainees protected under international humanitarian law - ICRC

[1] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 25 November 1939

[2] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 July 1940

[3] April Roach, https://www.romfordrecorder.co.uk/news/harold-wood-woman-shares-remembrance-day-story-1-6358280

[4] Prisoners of war and detainees protected under international humanitarian law - ICRC