Thomas Railway Trail: Box NATS History Trail 2

Lorne House to Middlehill Tunnel Claire Dimond and Alan Payne, July 2016

Lorne House to Middlehill Tunnel Claire Dimond and Alan Payne, July 2016

We started the walk with a mystery, Which of the pictures below is the odd one out? The answer emerged as we discovered more about the buildings and found the railway in Box that Awdry knew and used for events and characters in his books.

[PS - The answer to the question is at foot of this article.]

[PS - The answer to the question is at foot of this article.]

Rev Wilbert Awdry

The author of the Thomas the Tank Engine books, Rev Wilbert Awdry, wasn't born in Box but he came here aged 6 in 1911.

He lived in three different houses in the village, The Wilderness, Townsend and lastly Lorne Villa (now House), opposite the Tunnel entrance, where he lived with his parents between the ages of 9 and 17 years old. They renamed the house Journey's End. It was here that he heard the puffings and pantings of the two engines the conversation they were having with one another: "I can't do it! I can't do it! I can't do it!" and "Yes, you can! Yes, you can! Yes, you can!" as the trains fought their way up the incline in the Tunnel. He wrote the stories many years after he left the village, starting in 1943 with The Three Railway Engines for his son, Christopher, who had measles. Over the next thirty years, he published 26 books.

The books reflect life in the 1920s but they hearken back to the origins of the railway in Box, when the power of the engines was limited. The later stories also have overtones of contemporary life. The Fat Director was re-named Fat Controller after the 1948 nationalisation of the railways and the end of private directorships (note the Box spelling of the Controller's surname, Sir Topham Hatt). The first diesel train appeared in the books in 1958 and by 1968 the ending of steam was recorded on The Other Line.

The author of the Thomas the Tank Engine books, Rev Wilbert Awdry, wasn't born in Box but he came here aged 6 in 1911.

He lived in three different houses in the village, The Wilderness, Townsend and lastly Lorne Villa (now House), opposite the Tunnel entrance, where he lived with his parents between the ages of 9 and 17 years old. They renamed the house Journey's End. It was here that he heard the puffings and pantings of the two engines the conversation they were having with one another: "I can't do it! I can't do it! I can't do it!" and "Yes, you can! Yes, you can! Yes, you can!" as the trains fought their way up the incline in the Tunnel. He wrote the stories many years after he left the village, starting in 1943 with The Three Railway Engines for his son, Christopher, who had measles. Over the next thirty years, he published 26 books.

The books reflect life in the 1920s but they hearken back to the origins of the railway in Box, when the power of the engines was limited. The later stories also have overtones of contemporary life. The Fat Director was re-named Fat Controller after the 1948 nationalisation of the railways and the end of private directorships (note the Box spelling of the Controller's surname, Sir Topham Hatt). The first diesel train appeared in the books in 1958 and by 1968 the ending of steam was recorded on The Other Line.

Arrival of the Railway

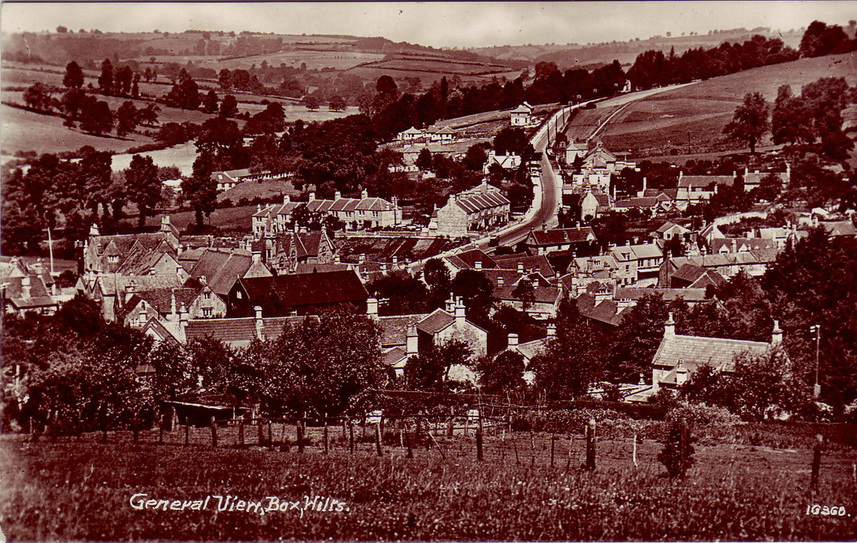

Box was a poor, rural area before the railway. John Britton wrote, The Beauties of Wiltshire: The situation of Box is extremely picturesque. Box Brook valley consists of fertile meadows, bounded by steep hills, over the sides of which are scattered hamlets, villas, and woods, forming a rich variety of scenery.

It was by no means certain that the railway would come through Box. The road engineer Macadam wanted a southern route via Marshfield and Wootton Bassett (avoiding Box) to access manufacturing at Trowbridge, Westbury and Warminster. Brunel disagreed, arguing for a northern line through Box to access Oxford, Cheltenham and Gloucester and to connect with north of England via the London and Birmingham Railway.

Problem with Box was Box Hill and the underground springs. Brunel had worked with his father on Rotherhithe Tunnel under the River Thames and was confident to deal with the water. Some opponents claimed that trains going through the tunnel would emerge with a load of corpses, and even if the journey did not prove fatal, no passengers would go twice ... if the brakes failed as the train entered the tunnel it would emerge at 120 mph (a rate at which) no human being could breathe. The Star road coach company advertised its services whereby passengers could disembark and use post chaise over Box Hill, joining with the eleven o'clock train on the Corsham side.

Box was a poor, rural area before the railway. John Britton wrote, The Beauties of Wiltshire: The situation of Box is extremely picturesque. Box Brook valley consists of fertile meadows, bounded by steep hills, over the sides of which are scattered hamlets, villas, and woods, forming a rich variety of scenery.

It was by no means certain that the railway would come through Box. The road engineer Macadam wanted a southern route via Marshfield and Wootton Bassett (avoiding Box) to access manufacturing at Trowbridge, Westbury and Warminster. Brunel disagreed, arguing for a northern line through Box to access Oxford, Cheltenham and Gloucester and to connect with north of England via the London and Birmingham Railway.

Problem with Box was Box Hill and the underground springs. Brunel had worked with his father on Rotherhithe Tunnel under the River Thames and was confident to deal with the water. Some opponents claimed that trains going through the tunnel would emerge with a load of corpses, and even if the journey did not prove fatal, no passengers would go twice ... if the brakes failed as the train entered the tunnel it would emerge at 120 mph (a rate at which) no human being could breathe. The Star road coach company advertised its services whereby passengers could disembark and use post chaise over Box Hill, joining with the eleven o'clock train on the Corsham side.

Building Box Tunnel

When it was built the Tunnel was the longest in the world at that time at 1¾ miles with a huge gradient of 1-in-100, a long haul over such a distance.The work to build it was divided between George Burge of Herne Bay, Kent, on eastern (Corsham) section of 1¼ miles and Messrs Brewer of Box and Lewis of Rudloe on the difficult western section of ½ mile.

George Burge was a very experienced engineer, having worked with Thomas Telford on the construction of St Katherine Dock, London, and with George Stephenson on Britain's first railway tunnel at Tyler Hill, Canterbury, Kent, which Brunel inspected in 1835. It was quite a coup for the Great Western Railway to get such a respectable contractor. Mr Gale, foreman for Burge, said the work took six years to complete. All the Burge work had to be bricked, so that it was one of the greatest undertakings in this country known up to that time. Thirty million bricks were made by Mr Hunt at Chippenham, and every week one ton of gunpowder and one ton of candles were consumed. Four thousand men were involved in the work at one time. Where did all those men live and sleep? In the neighbouring villages of Box and Corsham and being on day or night duty, as soon as one lot turned out another lot turned in, so that their beds were never empty.

The Brewer and Lewis section was through solid rock and wasn't brick-lined for many years. William Jones Brewer was reported as an elderly man, born in the neighbourhood. He had extensive quarry experience and he had started excavating the magnificent Cathedral in the Box Fields Quarry in the 1820s. In 1837 he went bankrupt and Box Tunnel was an attempt to get his money back.

The quarrymen working for Messrs Lewis and Brewer started at either end of vertical shafts sunk into Box Hill and worked towards each other in the centre, which they eventually achieved when To the joy of the workmen and to the triumph of Messrs Lewis and Brewer's scientific working, it was found that the junction was perfectly level the utmost deviation from a straight line was only one inch and a quarter.

When it was built the Tunnel was the longest in the world at that time at 1¾ miles with a huge gradient of 1-in-100, a long haul over such a distance.The work to build it was divided between George Burge of Herne Bay, Kent, on eastern (Corsham) section of 1¼ miles and Messrs Brewer of Box and Lewis of Rudloe on the difficult western section of ½ mile.

George Burge was a very experienced engineer, having worked with Thomas Telford on the construction of St Katherine Dock, London, and with George Stephenson on Britain's first railway tunnel at Tyler Hill, Canterbury, Kent, which Brunel inspected in 1835. It was quite a coup for the Great Western Railway to get such a respectable contractor. Mr Gale, foreman for Burge, said the work took six years to complete. All the Burge work had to be bricked, so that it was one of the greatest undertakings in this country known up to that time. Thirty million bricks were made by Mr Hunt at Chippenham, and every week one ton of gunpowder and one ton of candles were consumed. Four thousand men were involved in the work at one time. Where did all those men live and sleep? In the neighbouring villages of Box and Corsham and being on day or night duty, as soon as one lot turned out another lot turned in, so that their beds were never empty.

The Brewer and Lewis section was through solid rock and wasn't brick-lined for many years. William Jones Brewer was reported as an elderly man, born in the neighbourhood. He had extensive quarry experience and he had started excavating the magnificent Cathedral in the Box Fields Quarry in the 1820s. In 1837 he went bankrupt and Box Tunnel was an attempt to get his money back.

The quarrymen working for Messrs Lewis and Brewer started at either end of vertical shafts sunk into Box Hill and worked towards each other in the centre, which they eventually achieved when To the joy of the workmen and to the triumph of Messrs Lewis and Brewer's scientific working, it was found that the junction was perfectly level the utmost deviation from a straight line was only one inch and a quarter.

Stone Quarries

Having blasted through the stone it was realised that it was a useful building material if it was extracted whole as a rough block. Clift Quarry at the top of Box Hill started in 1865 by quarrying an adit (horizontal tunnel) straight into Box Hill. Blocks of stone were pulled through tunnel by horse and out of entrance by chain and horse gin. Excavation without using gunpowder involved chiselling downwards into the rock face, and using hammers, wedges and picks to extract a bock, all by hand. It then required to be hardened and shaped in stoneyards.

A track ran down Beech Road, parallel to the A4 and under the main road at The Bassetts to one stoneyard. The blocks were loaded onto trucks which free-wheeled down Box Hill, under A4 to the Wharf Stoneyard, now the site of The Bassetts. A ramp there to slow down the carriages. A steam engine pulled the trucks back up to Clift and the chimney of the engine house still exists in the garage of the house at Bath View.[1] Clift Quarry closed in 1968 but the indentation of the rail line from the quarry to the stone wharfs can still be seen at times.

A number of quarries are mentioned in Awdry's books. These include Anopha Quarry, a slate mine serviced by a narrow gauge railway very similar to the one at Clift. Other quarries include Blue Mountain Quarry, a large slate quarry where the engine Paxton takes stone from the quarry to Brendam Docks, and the Sodor China Clay Company who extracted material from the China Clay Pits.

Having blasted through the stone it was realised that it was a useful building material if it was extracted whole as a rough block. Clift Quarry at the top of Box Hill started in 1865 by quarrying an adit (horizontal tunnel) straight into Box Hill. Blocks of stone were pulled through tunnel by horse and out of entrance by chain and horse gin. Excavation without using gunpowder involved chiselling downwards into the rock face, and using hammers, wedges and picks to extract a bock, all by hand. It then required to be hardened and shaped in stoneyards.

A track ran down Beech Road, parallel to the A4 and under the main road at The Bassetts to one stoneyard. The blocks were loaded onto trucks which free-wheeled down Box Hill, under A4 to the Wharf Stoneyard, now the site of The Bassetts. A ramp there to slow down the carriages. A steam engine pulled the trucks back up to Clift and the chimney of the engine house still exists in the garage of the house at Bath View.[1] Clift Quarry closed in 1968 but the indentation of the rail line from the quarry to the stone wharfs can still be seen at times.

A number of quarries are mentioned in Awdry's books. These include Anopha Quarry, a slate mine serviced by a narrow gauge railway very similar to the one at Clift. Other quarries include Blue Mountain Quarry, a large slate quarry where the engine Paxton takes stone from the quarry to Brendam Docks, and the Sodor China Clay Company who extracted material from the China Clay Pits.

Stoneyards

In 1841 there were 110 quarry workers in Box and by 1901 the number had risen to 1,199. The total population of the village doubled. Most quarrymen worked in stoneyards, rather than underground, stacking stone for hardening, sawing into blocks, measuring for architectural needs (especially building repairs), loading onto rail carriages, looking after horses, blacksmith work and sharpening tools.

The village had more than seven stone yards, employing hundreds of men, including The Wharf, five independent yards at Box Railway Station, one up at Longsplatt and another at Sheppard's Yard on Box Hill. The Wharf was dangerous place to work. In 1888 a 13 year-old boy, Frank Bradfield, who had been employed for four months minding the horses, was crushed leading a horse pulling a loaded stone truck on the tramway when he was trapped against a pile of stationary stone.

Box stone became a nation-wide commodity and in 1860 a price list was issued for the delivery of the stone by rail to most towns in England. The Duke of Wellington had his house at Hyde Park Corner re-faced in Box Ground stone as a tribute to his wartime victories.[2] The reputation of Box freestone was outstanding and it was transported throughout the world, even to Canada and South Africa, where it was used to face the Town Hall in Cape Town.[3]

In 1841 there were 110 quarry workers in Box and by 1901 the number had risen to 1,199. The total population of the village doubled. Most quarrymen worked in stoneyards, rather than underground, stacking stone for hardening, sawing into blocks, measuring for architectural needs (especially building repairs), loading onto rail carriages, looking after horses, blacksmith work and sharpening tools.

The village had more than seven stone yards, employing hundreds of men, including The Wharf, five independent yards at Box Railway Station, one up at Longsplatt and another at Sheppard's Yard on Box Hill. The Wharf was dangerous place to work. In 1888 a 13 year-old boy, Frank Bradfield, who had been employed for four months minding the horses, was crushed leading a horse pulling a loaded stone truck on the tramway when he was trapped against a pile of stationary stone.

Box stone became a nation-wide commodity and in 1860 a price list was issued for the delivery of the stone by rail to most towns in England. The Duke of Wellington had his house at Hyde Park Corner re-faced in Box Ground stone as a tribute to his wartime victories.[2] The reputation of Box freestone was outstanding and it was transported throughout the world, even to Canada and South Africa, where it was used to face the Town Hall in Cape Town.[3]

|

Mill Lane Halt

Mill Lane Halt (sometimes called Woodstock Station) opened on 31 March 1930 after Rev Awdry had left the village. It was a make-do station to satisfy the needs of villagers to have a local access point. It cost only £800, originally a single timber platform, later replaced by two concrete-based platforms with corrugated iron shelters for passengers. The platform length could only accommodate the last four carriages on a train, which had to pull up appropriately. A small corrugated iron and wooden ticket office box existed at the bottom of very steep steps on Mill Lane where tickets were issued and checked. The senior porter manned the ticket office. Left: The only known picture of the ticket hut, seen on the right (photo courtesy Richard Pinker) |

Box Station

Box Staion behind the Northey Arms was far away from the village centre when it was built in 1841. At that time the Blind House marked edge of the village residential area and the houses on the High Street were just open fields. It wasn't built for the convenience of the public and wasn't even ready when the line opened. A report in October 1841 refers to its poor condition in such a dreadful state, owing to the late rains, that the inhabitants of Box and Ashley, particularly females, cannot wade through the mud and clay to go by the trains, so that they prefer the conveyance of the coaches.

It was positioned where land was available and where the a level rail track could be obtained before the incline in Box Tunnel.

The owners of Shockerwick House were reputed to oppose the railway on their land, so the Northey family demolished the ancient Cuttings Mill on their estate and built the Northey Arms as a Railway Hotel, just up from station, to take advantage of the economic opportunity of a railway link.

Rather, the siting of the station was for the needs of the banker engine, needed to provide additional power to get trains through the gradient of the Box Tunnel. A shed for the banker engine was built in February 1842 and three years later a water supply was incorporated for the engine's steam needs. JC Bourne confirmed the importance of the banker engine in 1846: The Box Station is 101¾ miles from London and 5 from Bath. This is at the foot of the Box inclined plane, and the place at which the assistant engine stands in readiness to assist the regular engine; the mail train however, being light, runs up without that assistance.

The banker engine is the closest engine to Thomas the Tank Engine. It was severely overworked and was replaced every week when a different one was sent out from Swindon. The shed closed on 24 February 1919 when engine power had improved sufficiently and Awdry's depiction of Thomas is partly based on nostalgia.

Box Staion behind the Northey Arms was far away from the village centre when it was built in 1841. At that time the Blind House marked edge of the village residential area and the houses on the High Street were just open fields. It wasn't built for the convenience of the public and wasn't even ready when the line opened. A report in October 1841 refers to its poor condition in such a dreadful state, owing to the late rains, that the inhabitants of Box and Ashley, particularly females, cannot wade through the mud and clay to go by the trains, so that they prefer the conveyance of the coaches.

It was positioned where land was available and where the a level rail track could be obtained before the incline in Box Tunnel.

The owners of Shockerwick House were reputed to oppose the railway on their land, so the Northey family demolished the ancient Cuttings Mill on their estate and built the Northey Arms as a Railway Hotel, just up from station, to take advantage of the economic opportunity of a railway link.

Rather, the siting of the station was for the needs of the banker engine, needed to provide additional power to get trains through the gradient of the Box Tunnel. A shed for the banker engine was built in February 1842 and three years later a water supply was incorporated for the engine's steam needs. JC Bourne confirmed the importance of the banker engine in 1846: The Box Station is 101¾ miles from London and 5 from Bath. This is at the foot of the Box inclined plane, and the place at which the assistant engine stands in readiness to assist the regular engine; the mail train however, being light, runs up without that assistance.

The banker engine is the closest engine to Thomas the Tank Engine. It was severely overworked and was replaced every week when a different one was sent out from Swindon. The shed closed on 24 February 1919 when engine power had improved sufficiently and Awdry's depiction of Thomas is partly based on nostalgia.

Changes Arising from the Railway

As well as employment in stoneyards, the creation of Box Hill hamlet and the rise of Methodist chapels there were many changes that we take for granted now. The railway altered the time of day in Box by about 10 minutes when the village adopted Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). The first published timetable in the 1840s GWR reported schedule of local times and separate column for major towns en route, which was too complicated so the whole country moved to GMT, based on London time.

The railway line totally altered the road system at Ashley. A new L-shaped road was built from the old turnpike road at the point where the A4 and Ashley Lane meet (now the petrol garage). The new road carried on to Box Railway Station and then looped back to the old turnpike road at Shockerwick. This route soon became the main highway from Box to Bath. Another road was constructed from the railway station up to Middlehill. It was built as a promenade for the convenience of passengers accessing the railway facilities, tree-lined and with a pavement, very unusual.

In the centre of the village, the height of the old High Street was levelled for the convenience of carriages hauling stone to Box Station stoneyard. The road outside The Hermitage was lowered and the part outside the modern Co-op shop was raised. New houses sprung up everywhere to accommodate the population increase including properties on Fairmead View which was built and let to quarry labourers at a rent of a farthing a week.

As well as employment in stoneyards, the creation of Box Hill hamlet and the rise of Methodist chapels there were many changes that we take for granted now. The railway altered the time of day in Box by about 10 minutes when the village adopted Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). The first published timetable in the 1840s GWR reported schedule of local times and separate column for major towns en route, which was too complicated so the whole country moved to GMT, based on London time.

The railway line totally altered the road system at Ashley. A new L-shaped road was built from the old turnpike road at the point where the A4 and Ashley Lane meet (now the petrol garage). The new road carried on to Box Railway Station and then looped back to the old turnpike road at Shockerwick. This route soon became the main highway from Box to Bath. Another road was constructed from the railway station up to Middlehill. It was built as a promenade for the convenience of passengers accessing the railway facilities, tree-lined and with a pavement, very unusual.

In the centre of the village, the height of the old High Street was levelled for the convenience of carriages hauling stone to Box Station stoneyard. The road outside The Hermitage was lowered and the part outside the modern Co-op shop was raised. New houses sprung up everywhere to accommodate the population increase including properties on Fairmead View which was built and let to quarry labourers at a rent of a farthing a week.

Myth and Reality

The tunnel was nearly closed on the very first day. The first train to attempt the climb was The Meridian with Brunel on board but it had to wait four hours because there was only a single line which required navvies to make a crossover track from the up line to the down line in order to finish the journey.

Daniel Gooch, engineer, reported That night we had a very narrow escape of a fearful accident. I was going up the tunnel with the last up train when I fancied I saw some green lights, placed as they were in front of our trains. A second's reflection convinced me it was the mail coming down. I lost no time in reversing the engine I was on and running back to Box Station with my train as quickly as I could, when the mails came down close behind me. The policeman at the top of the tunnel had made some blunder and sent the mails on when they arrived there. Had the tunnel not been pretty clear of steam we must have met in full career and the smash would have been fearful, cutting short my career also.

Light through the tunnel at dawn on Brunel's birthday (9 April). First mentioned in April 1842 with a report that Box Tunnel presented a most splendid appearance ... on Saturday last (16 April) caused by the shining of the sun directly through it and giving the walls a brilliancy ... as though the whole tunnel had been gilt. We intend to solve this allegation in a new series about Railways and Quarries in Box to be published in 2017.

The tunnel was nearly closed on the very first day. The first train to attempt the climb was The Meridian with Brunel on board but it had to wait four hours because there was only a single line which required navvies to make a crossover track from the up line to the down line in order to finish the journey.

Daniel Gooch, engineer, reported That night we had a very narrow escape of a fearful accident. I was going up the tunnel with the last up train when I fancied I saw some green lights, placed as they were in front of our trains. A second's reflection convinced me it was the mail coming down. I lost no time in reversing the engine I was on and running back to Box Station with my train as quickly as I could, when the mails came down close behind me. The policeman at the top of the tunnel had made some blunder and sent the mails on when they arrived there. Had the tunnel not been pretty clear of steam we must have met in full career and the smash would have been fearful, cutting short my career also.

Light through the tunnel at dawn on Brunel's birthday (9 April). First mentioned in April 1842 with a report that Box Tunnel presented a most splendid appearance ... on Saturday last (16 April) caused by the shining of the sun directly through it and giving the walls a brilliancy ... as though the whole tunnel had been gilt. We intend to solve this allegation in a new series about Railways and Quarries in Box to be published in 2017.

References

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.37

[2] Alec Clifton-Taylor, The Pattern of English Building, p.37-8

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.249

[1] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.37

[2] Alec Clifton-Taylor, The Pattern of English Building, p.37-8

[3] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.249

Answer

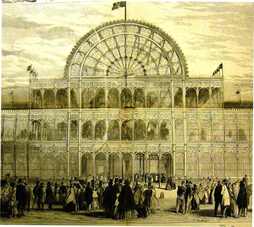

It is Brunel's Tunnel (left) dated 1841 that is the odd-one out (illustration by JC Bourne of Box Tunnel in 1846, courtesy Rose Ledbury). All of the buildings were constructed within a decade in the 1830s and 1840s. The Houses of Parliament (centre, Claude Monet's picture of 1903 courtesy Wikipedia) were built a few years after a fire destroyed much of the Palace of Westminster in 1834. The architect Augustus Pugin, a Roman Catholic, designed them in the very latest Gothic style to enable a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages. Brunel saw the buildings with their massive glass windows and iron girders when he was working on the Rotherhithe Tunnel with his father. This style was repeated later when the Crystal Palace opened for the Great Exhibition in 1851 (courtesy Wikipedia)..

Brunel turned against the latest craze in architecture to make Box Tunnel resemble the Classical buildings of the Roman era. As such, he wanted to make the Tunnel a statement of the importance, longevity and power of the new railway age.

It is Brunel's Tunnel (left) dated 1841 that is the odd-one out (illustration by JC Bourne of Box Tunnel in 1846, courtesy Rose Ledbury). All of the buildings were constructed within a decade in the 1830s and 1840s. The Houses of Parliament (centre, Claude Monet's picture of 1903 courtesy Wikipedia) were built a few years after a fire destroyed much of the Palace of Westminster in 1834. The architect Augustus Pugin, a Roman Catholic, designed them in the very latest Gothic style to enable a return to the faith and the social structures of the Middle Ages. Brunel saw the buildings with their massive glass windows and iron girders when he was working on the Rotherhithe Tunnel with his father. This style was repeated later when the Crystal Palace opened for the Great Exhibition in 1851 (courtesy Wikipedia)..

Brunel turned against the latest craze in architecture to make Box Tunnel resemble the Classical buildings of the Roman era. As such, he wanted to make the Tunnel a statement of the importance, longevity and power of the new railway age.