Sheppard Stoneyard Workers Text and photographed by Vaughan Hill November 2022

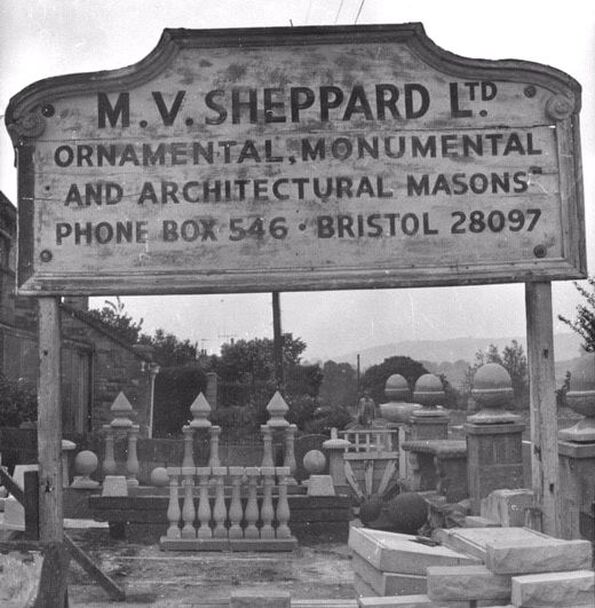

Vaughan Hill found old photographs of work at the stoneyard run by Maurice Sheppard on Box Hill. He had taken them in 1970 using a Rolliflex twin lens 120 format camera on his first year at Bath Academy of Art (Corsham) as a Diploma in Art & Design Student. He told us: “Part of the course was photography and I was just going round the locale looking for subject matter and discovered the yard going down Box Hill. The pictures exemplify the labour-intensity required then to just get one stone column ready for the lathe.”

Maurice Sheppard

The owner of the yard, Maurice Vernon Sheppard (24 July 1917-1975), was an unusual man, swimming against the tide of a changing world in post-war Britain with a trade rooted in a century earlier. He was the third generation of stonemasons with wide connections in the trade. Maurice was connected with many masons - related to the Fido family of quarrymen who lived at Boxfields; he had trained with his uncle Alfred Ethelbert Sheppard (1885-1957); and his uncle Reginald William Sumsion, son of a Kingsdown quarrying family, was his best man at his wedding. Maurice had operated a stonemasonry business in West Bromwich in the years around the Second World War in partnership with Stephen Ernest Birch. When his uncle Alfred retired, the partnership was dissolved in August 1946 by mutual agreement and Maurice returned to Box to take over the local business on Box Hill. He worked hard to generate trade in the austerity years of post-war Box, including showing small works at the Chippenham Flower Show.[1]

The owner of the yard, Maurice Vernon Sheppard (24 July 1917-1975), was an unusual man, swimming against the tide of a changing world in post-war Britain with a trade rooted in a century earlier. He was the third generation of stonemasons with wide connections in the trade. Maurice was connected with many masons - related to the Fido family of quarrymen who lived at Boxfields; he had trained with his uncle Alfred Ethelbert Sheppard (1885-1957); and his uncle Reginald William Sumsion, son of a Kingsdown quarrying family, was his best man at his wedding. Maurice had operated a stonemasonry business in West Bromwich in the years around the Second World War in partnership with Stephen Ernest Birch. When his uncle Alfred retired, the partnership was dissolved in August 1946 by mutual agreement and Maurice returned to Box to take over the local business on Box Hill. He worked hard to generate trade in the austerity years of post-war Box, including showing small works at the Chippenham Flower Show.[1]

Examples from 1970 of the yard’s typical products

In February 1953 his business was selected for a major article in The Wiltshire Times, chosen as one of the country’s traditional crafts, the stone trade of Corsham and Box.[2] Although by then the business was mainly ornamental pieces and repair items, Maurice’s stoneyard was chosen to represent this highly-skilled and strongly individualistic craft. In 1953 Maurice’s yard was recorded as employing 20 men. They specialised in monumental headstones and re-carving tracery windows which had been damaged in churches in the Second World War. They also made ornamental garden ornaments (such as bird baths and sundials) which were popular with peacetime gardeners.

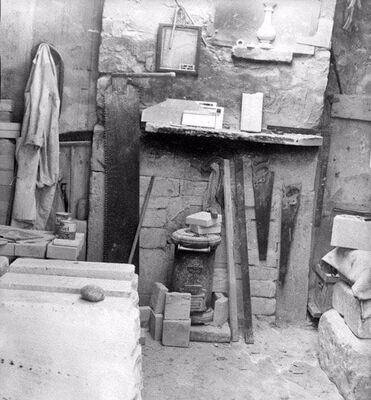

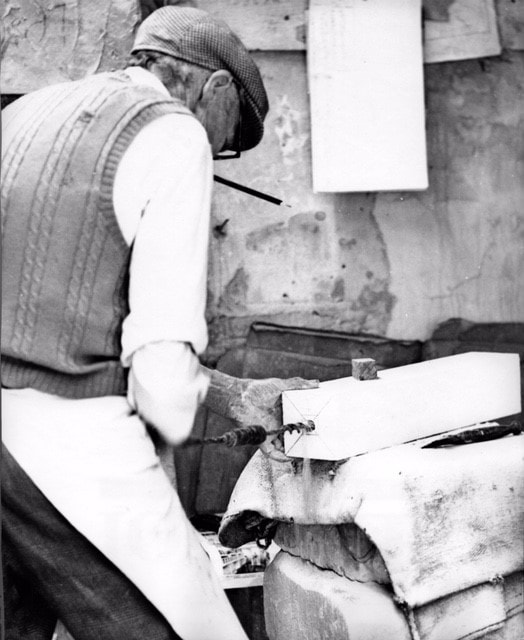

I took these photos in the sequence of starting a pillar-build process. They begin with a general view of the yard and the raw materials stacked there. The blocks were hardening before being processed by the masons. A key element of the process was to accurately measure the stone and to plan how to maximise the use of blocks. As such designers and planners were a vital part of the workforce, a role often undertaken by the owner, whose profit was at stake.

|

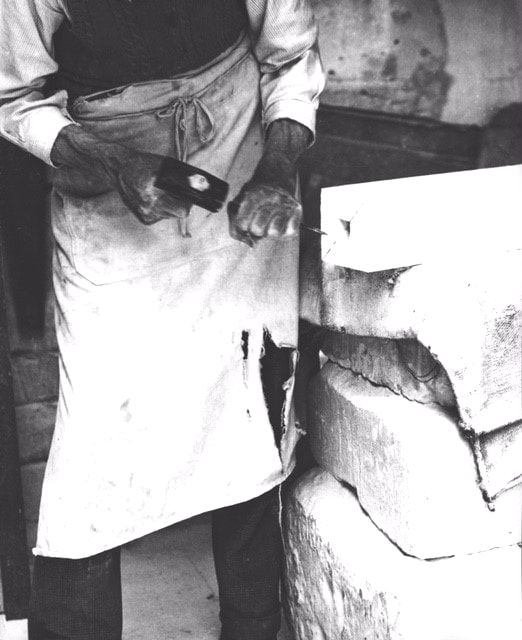

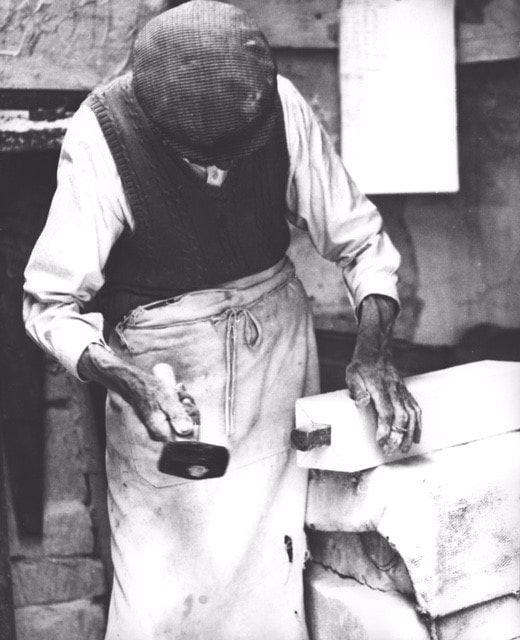

Masons’ Techniques The first job was to square off large blocks into usable sizes, in the case of pillars this meant square-section columns. The main tool for this was the frig bob saw (seen right). This was a single-person saw, often operated with two hands on the handle and thumbs crossed to exert pressure by both arms. The saw teeth needed constant sharpening on the fore and rear sides of each tooth and setting the teeth by splaying them slightly outwards.[3] In the photograph right, pressure on the top of the saw has been increased by a weight to ease the demand on the sawyer and give a better finish to the cut edge. Right: The frig bob saw was little changed from the Victorian period |

|

The stoneyards were usually sited on firm, flat ground where angles of cut were not distorted by inclines.[4] They were often outside of the residential areas because of the amount of stone dust generated. The work was usually undertaken substantially in the open air but under a roof covering. One side of the yard often had a wall for protection against the elements, leaving the other three sides open. This arrangement enabled workers to continue in inclement weather. In addition, there was often a fully-enclosed shed made of corrugated iron where workers could take shelter to enjoy more warmth at break times. Left: Tools and materials round the sole heating system |

|

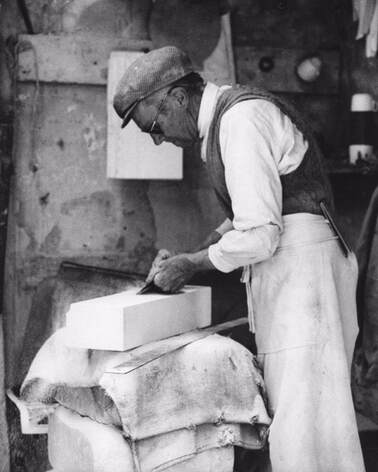

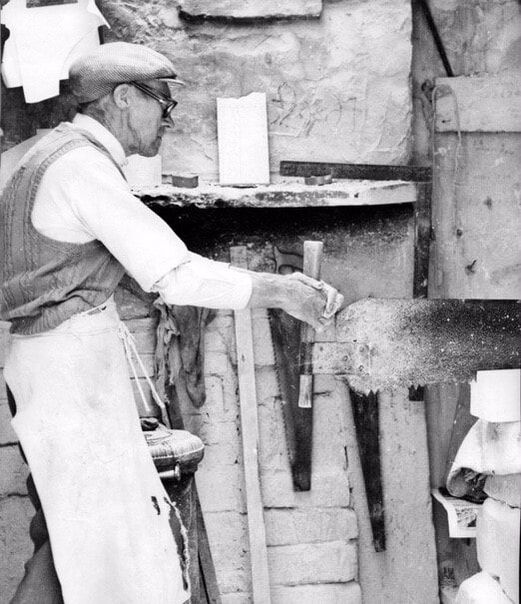

For many ornamental stone features the finish on the stonework was vital. Customers wanted smooth, ashlar surfaces to show off the masonry.

Of course, this was one of the dustiest jobs, despite the use of material to catch the dust. Around the year 1900 Elsie Blanche Sealey, a schoolgirl from Bath, commented on the stone dust in the village caused by the stone yards: Box Station siding was full of its whiteness.[5] There are a number of buildings in the village described by the word White, indicating new stone in areas away from the stoneyards where everything was covered white. For example, The White Wall at the junction of Ashley Lane and the A4, and White Cottage on Doctors Hill. Nowadays the process of giving a smooth finish uses wet drill polishing. Right: Herbie Smith giving a smooth finish to a piece. |

|

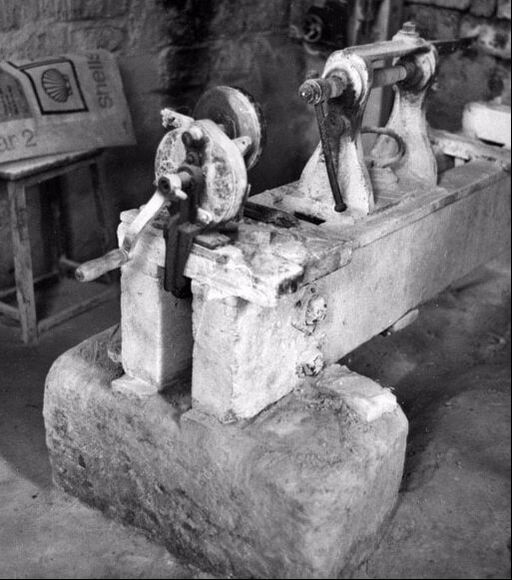

The fine sculptured contours of pillars were formed using a lathe with chisels cutting the stone as it rotated with the chisel being held stationary against a stanchion. Whether this lathe was still in use in the 1970s is uncertain and more likely an electric lathe would have been used.

Much of the work in the 1950s involved repair to churches and significant buildings which had suffered damage during the Second World War. For repair work on ornate pieces, such as church windows and statues, precision was vital. This necessitated absolutely precise measurements to enable the repair to be installed without causing further damage. This was a job usually undertaken by the yard owner, whilst the installation work went to the journeyman mason. To enable the stone to be cut precisely, a stable base was required and the ability to hold the stone securely in the event that the task lasted more than a single work shift. Left: An old hand-operated stone lathe |

Above: Three stages taken to insert wooded pegs either end for mounting in a lathe: (a) drill circular hole

(b) chisel square hole [so peg will not rotate] (c) tap in wooden pegs.

(b) chisel square hole [so peg will not rotate] (c) tap in wooden pegs.

Staff Employed

The Wiltshire Times newspaper article recalled the workmen in the yard in 1953:

Bertie John Wright (1898-18 August 1959), manager who lived at 31 Fairmead View and was active at Box Church.

John Rollins King (1888-1966) from Quarry Hill. John King was a very well-known person in Box and can be seen in articles on the website about Early Guides and Children’s Clubs). In the words of the newspaper, he gave devoted work as superintendent of the St John Ambulance Division and for his rose growing. He was a specialist in church restoration with over 50 years of experience in the trade and had worked on buildings throughout Britain, including Canada House, London.

The Wiltshire Times newspaper article recalled the workmen in the yard in 1953:

Bertie John Wright (1898-18 August 1959), manager who lived at 31 Fairmead View and was active at Box Church.

John Rollins King (1888-1966) from Quarry Hill. John King was a very well-known person in Box and can be seen in articles on the website about Early Guides and Children’s Clubs). In the words of the newspaper, he gave devoted work as superintendent of the St John Ambulance Division and for his rose growing. He was a specialist in church restoration with over 50 years of experience in the trade and had worked on buildings throughout Britain, including Canada House, London.

|

Samuel Alfred Sheppard, father of Maurice (1897-) had trained as an apprentice in Corsham under EW Head. His specialism was in turning balusters (decorative pillars). John Griffin (1916-) of 90 Priory Street, Corsham, led a team of eight men doing the on-site fixing in the buildings needing repair, including Britannia House, opposite The Old Bailey in London. John had been involved in a tragedy in 1938 when his mother Louise and sister Gladys were killed in a car crash in which John was also a passenger but survived although injured.[6] Herbie Smith (1908-1988) lived at Hilden, Box Hill James P Carpenter (1914-), who lived at Panorama, Box Hill, was responsible for carving lettering in all types of stone, including work at Buckingham Palace (see Carpenter Family). Gordon Fortune (1935-1995) was still an apprentice. Right: John Griffin in 1938 when he survived in the tragic motor accident (courtesy Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 November 1938) |

|

Left: Herbie Smith at work sawing another block to size for the next pillar The article spoke of the stonemasons as if they were craftsmen in an ancient industry. That wasn’t really true because the industry had only become widespread in Box in the 1870s. Its economic impact was such that it had achieved public reverence locally. The end of the industry was obvious after the war and Sheppard’s yard closed shortly after Vaughan captured these photographs. Maurice took the decline personally, unable to do anything to improve the deteriorating situation and in despair about the future. He died in tragic circumstances in 1975. The demise of an industry is always a tragedy for an area but worse still for those involved, often after trying hard to keep a struggling business going. Often there is the feeling of failure and self-questioning for those involved with questions about how things could have been different. The impact is widespread: on the owner, the staff employed and their families. |

For an area, the demise of whole industries is devastating because the workforce is often elderly and incapable of re-training or unable to move to new areas. The closure of the coal mines, steel works and the car industry throughout Britain has caused economic collapse and structural unemployment. We have seen it happen first-hand in the Box stone trade but we have been fortunate that we are conveniently located to Bristol, Swindon and London with good infrastructure of roads to get to many parts of the country. That wasn’t the case for the old staples of British industries after the Second World War.

References

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 9 August 1952

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 28 February 1953

[3] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.92-93

[4] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.461

[5] Elsie B Sealy, My Memoirs, p.4

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 12 November 1938

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 9 August 1952

[2] The Wiltshire Times, 28 February 1953

[3] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.92-93

[4] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.461

[5] Elsie B Sealy, My Memoirs, p.4

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 12 November 1938