Stonemasons Part 1:

Operative Society of Stonemasons and Quarrymen

Jane Hussey and Alan Payne March 2021

Operative Society of Stonemasons and Quarrymen

Jane Hussey and Alan Payne March 2021

When Charles Dickens wrote about the conditions of the labouring poor in England, he focused on child exploitation and child labour in the workhouse and orphanage. He only touched on the situation of adult labour in the novel “Hard Times” written in 1854. This depicted factory hands in an imaginary northern town, often taken to represent Manchester but he had no sympathy for strikes or withdrawal of labour. Instead, the novel proposed morality and imagination, rather than pay rises, to solve deprivation and social hardship. This was very much a middle-class Victorian view of labour relations.

Local and National Unrest

The Chartist movement of the late 1830s and 1840s was essentially a political struggle wanting universal male franchise and parliamentary reform. It struck chords with the working classes and has sometimes been seen as a forerunner of the organisation of the proletariat and trade unions. Bath had a long history of involvement based on the Working Men’s Association in Monmouth Street and led the regional disruption.[1] At Whitsun 1839 a Chartist meeting was called in Bath inviting supporters from Bath, Bristol, Trowbridge, Bradford, Frome, Westbury and other local places.[2] The authorities took panic and swore in hundreds of special constables. Three thousand supporters were alleged to have attended; the cheer went up Men of England! Why stand ye in Jeperde? (sic) and there were calls for the People’s Charter to be adopted. Some supporters surrounded the Guildhall, Bath, and the police force armed with cutlasses, several troops of the West Somerset Yeomanry Cavalry, a troop of Hussars … were ready to act in any case of emergency. The Duke of Beaufort raised the matter in the House of Lords and the Duke of Wellington, former prime minister, commented upon the Bath situation.[3]

Further meetings followed: over 5,000 at Beacon Hill Common, Bath in August, 2,000 colliers of Radstock, Timsbury and Newton joined the movement, and the Bath Chartists moved into Newport, South Wales.[4] The capture at Blackwood of John Roberts, a Chartist-supporting Bath solicitor, made national headlines. The authorities began charging offenders and a report in March 1840 claimed that 128 male and 25 female Chartist prisoners were held in Bath.[5] The influence of the Bath Chartist Association diminished and it merged with other groups.

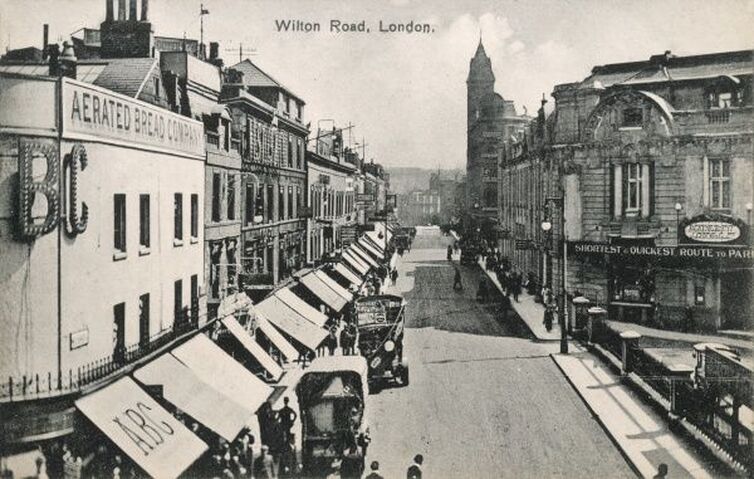

World events in 1848 turned public opinion against any extension of the franchise for decades. The fear of the Victorian middle classes was of revolution similar to that of the French Revolution and the 1848 uprisings in much of Europe which emerged in France, Italy, Germany, Hungary and elsewhere. The French king abdicated and fled to England, Queen Victoria took refuge on the Isle of Wight in case of civil unrest, and a huge Chartist rally was held in London, pictured above. The following year, shots were fired at Queen Victoria and later she was attacked by an Irishman complaining about the appalling potato famine there.

Against this backdrop, the government saw no role for working-class organisations in industrial relations. Middle-class Liberal sympathisers turned to utilitarian ideas (promoting concepts of happiness for general public), keen on temperance, free trade and efficiency. There was little political desire to legalise membership of trade unions which remained a criminal offence until 1871.

Operative Society of Stonemasons and Quarrymen

The Society of Stonemasons and Quarrymen (OSM) started as a loose collection of local friendly societies in 1831 and evolved into a trade union. The London lodge was an early advocate of a nine-hour working day for employees and called a strike in 1841, halting work on the new Houses of Parliament (the present building). At first the complaint was against Mr Allen, the foreman of Messrs Grissell and Peto, who the society alleged showed insufficient care of a man who fell from scaffolding and broke his leg, and three cases of dismissal of masons for taking time off to care for sick and dying relatives, all repudiated.[6] By October 1841 the strike at Parliament brought similar action from other sites of the same contractor which were involved in work to build Nelson’s Column and at the Woolwich Steam Works.[7] The strike at the Houses of Parliament lasted for over 8 months.

The strike by the London Lodge wasn’t the only case of unrest amongst stonemasons and in 1854 the Doncaster men stopped work on a new parish church claiming that “rubble wallers” and others were encroaching upon our trade.[8] They objected to having their individual names called for permission to have lunch breaks and wanted two hours travel time to site. The strikers were dismissed peremptorily. The contractors looked to employ other men and a few German masons were obtained in London.[9] There was simmering unrest in other areas – at Bradford where 400 masons wanted guaranteed wages of 28s per week and a reductions of their 57½ hours per week, at Halifax where two black sheep or non-unionist were employed, and at Leeds in 1860.[10]

Reaction in Box, 1859-61

Against this background of militancy, it was inevitable that stonemasons in Box would be affected and they were drawn into another London dispute in 1859 when thousands of members of the London branch of the Operative Society of Masons went on strike. The union was seeking to stop payment of wages by the hour and to reduce the hours of work from 10 hours to 9 hours per day for six days a week. The dispute was originally concentrated on a single site operated by contractors Messrs Trollope at Wilton Place, Pimlico where the contractor had offered payment of just £2 to the widow of an employee killed on site.[11]The masons were joined by other building unions and a regional London building strike developed. In response, an amalgamation of Master Builders locked out 24,000 employees in London, insisting that they return to their sites and sign a non-union declaration. Against this background, the OSM sought to raise support from members in Box, which branch had been formed in 1857.

The Chartist movement of the late 1830s and 1840s was essentially a political struggle wanting universal male franchise and parliamentary reform. It struck chords with the working classes and has sometimes been seen as a forerunner of the organisation of the proletariat and trade unions. Bath had a long history of involvement based on the Working Men’s Association in Monmouth Street and led the regional disruption.[1] At Whitsun 1839 a Chartist meeting was called in Bath inviting supporters from Bath, Bristol, Trowbridge, Bradford, Frome, Westbury and other local places.[2] The authorities took panic and swore in hundreds of special constables. Three thousand supporters were alleged to have attended; the cheer went up Men of England! Why stand ye in Jeperde? (sic) and there were calls for the People’s Charter to be adopted. Some supporters surrounded the Guildhall, Bath, and the police force armed with cutlasses, several troops of the West Somerset Yeomanry Cavalry, a troop of Hussars … were ready to act in any case of emergency. The Duke of Beaufort raised the matter in the House of Lords and the Duke of Wellington, former prime minister, commented upon the Bath situation.[3]

Further meetings followed: over 5,000 at Beacon Hill Common, Bath in August, 2,000 colliers of Radstock, Timsbury and Newton joined the movement, and the Bath Chartists moved into Newport, South Wales.[4] The capture at Blackwood of John Roberts, a Chartist-supporting Bath solicitor, made national headlines. The authorities began charging offenders and a report in March 1840 claimed that 128 male and 25 female Chartist prisoners were held in Bath.[5] The influence of the Bath Chartist Association diminished and it merged with other groups.

World events in 1848 turned public opinion against any extension of the franchise for decades. The fear of the Victorian middle classes was of revolution similar to that of the French Revolution and the 1848 uprisings in much of Europe which emerged in France, Italy, Germany, Hungary and elsewhere. The French king abdicated and fled to England, Queen Victoria took refuge on the Isle of Wight in case of civil unrest, and a huge Chartist rally was held in London, pictured above. The following year, shots were fired at Queen Victoria and later she was attacked by an Irishman complaining about the appalling potato famine there.

Against this backdrop, the government saw no role for working-class organisations in industrial relations. Middle-class Liberal sympathisers turned to utilitarian ideas (promoting concepts of happiness for general public), keen on temperance, free trade and efficiency. There was little political desire to legalise membership of trade unions which remained a criminal offence until 1871.

Operative Society of Stonemasons and Quarrymen

The Society of Stonemasons and Quarrymen (OSM) started as a loose collection of local friendly societies in 1831 and evolved into a trade union. The London lodge was an early advocate of a nine-hour working day for employees and called a strike in 1841, halting work on the new Houses of Parliament (the present building). At first the complaint was against Mr Allen, the foreman of Messrs Grissell and Peto, who the society alleged showed insufficient care of a man who fell from scaffolding and broke his leg, and three cases of dismissal of masons for taking time off to care for sick and dying relatives, all repudiated.[6] By October 1841 the strike at Parliament brought similar action from other sites of the same contractor which were involved in work to build Nelson’s Column and at the Woolwich Steam Works.[7] The strike at the Houses of Parliament lasted for over 8 months.

The strike by the London Lodge wasn’t the only case of unrest amongst stonemasons and in 1854 the Doncaster men stopped work on a new parish church claiming that “rubble wallers” and others were encroaching upon our trade.[8] They objected to having their individual names called for permission to have lunch breaks and wanted two hours travel time to site. The strikers were dismissed peremptorily. The contractors looked to employ other men and a few German masons were obtained in London.[9] There was simmering unrest in other areas – at Bradford where 400 masons wanted guaranteed wages of 28s per week and a reductions of their 57½ hours per week, at Halifax where two black sheep or non-unionist were employed, and at Leeds in 1860.[10]

Reaction in Box, 1859-61

Against this background of militancy, it was inevitable that stonemasons in Box would be affected and they were drawn into another London dispute in 1859 when thousands of members of the London branch of the Operative Society of Masons went on strike. The union was seeking to stop payment of wages by the hour and to reduce the hours of work from 10 hours to 9 hours per day for six days a week. The dispute was originally concentrated on a single site operated by contractors Messrs Trollope at Wilton Place, Pimlico where the contractor had offered payment of just £2 to the widow of an employee killed on site.[11]The masons were joined by other building unions and a regional London building strike developed. In response, an amalgamation of Master Builders locked out 24,000 employees in London, insisting that they return to their sites and sign a non-union declaration. Against this background, the OSM sought to raise support from members in Box, which branch had been formed in 1857.

The union put great pressure on local employees to join the strike and held several meetings in the village. In October 1861 a local newspaper reported the outcome of one such attempt: in consequence of the great esteem in which the masters of the various firms of this locality are held by the men, the latter considered it a duty to their employers .. to disregard .. these agitators.[12] A dinner was organised by Box contractors for 120 local employees at the Northey Arms Hotel to further encourage loyalty. Speeches, songs and alcohol were mixed with toasts of loyalty made by Mr Lambert (for 14 years the agent of Mr Myers of the Box Stoneyards) and Messrs Cole, Pictor, Strong and others showing the evils of strikes and the unreasonableness of the present demand. The newspaper report is clearly prejudiced but, having said that, there was no apparent desire to strike in Box.

There had been a close connection between employers and workers, such as Lewis and Brewer, the contractors excavating the eastern section of Box Tunnel, who had induced the men to contribute to a fund, from which the sick receive 1s a day and those who have met with accidents 1s.6d a day each... this plan has given general satisfaction to the men whose liberal wages enable them by a small sacrifice to provide.[13] The local ganger system, based on sons working for fathers, probably connected employers with workers and enforced a hierarchy in the trade.

There were further strikes by London masons. One in 1877 complained that the importation of foreign workmen continues.[14]

A local newspaper reported: the stone trade of Corsham and Box is in a very depressed state at present .. many of the freestone masons are out of work. They blamed The Masters’ Union who have decided to prohibit the introduction of worked stone into the large towns of the kingdom.[15] The reference to worked stone is interesting because it suggests that the skill premium of master masons in the local market was being threatened, possibly facilitated through the railways.

Unions in Box

These early unions consisted of skilled men who limited entry to their trades. They could be subcontractors or sometimes small employers, such as the gang system in Box quarries. The trade was highly stratified differentiating skilled (banker and journeymen) masons and unskilled (labourer and underground miner) members. Often with high income levels, some of these masons were able to save so it's not surprising that the Operatives Society started as a friendly society.

John Shell (25 Feb 1828 -1 February 1902) was the first foreman and later manager at Box Wharf, operated by the Pictor family for their Clift Quarry Works. He was the son of Robert (b 1801) and Sarah (b 1799) and grew up as part of a quarry family who lived at Box Quarries in 1841. He was admitted to the Box Lodge of the Operative Society of Masons and Quarrymen in 1857, paying one shilling contribution in 1858. He and his family were possibly members of the Plymouth Brethren at the Quarry Hill Chapel, which may have influenced his social conscience.[16] In 1881 he was recorded as Master mason (employs 7 men and 5 boys) whilst living at 3 Bridge Cottages (assumed to refer to Wharf Cottages). He died at Reading in 1902.[17]

Although there was no concerted effort by the Box quarrymen to strike, there were intermittent disruptions. One such was in 1876 when the Box Hill day men came out demanding an extra 2 shillings (10p) per week.[18] They were supported by the Bathford miners and threatened to bring 1,500 men out on strike. A ganger wrote an open letter in 1889 saying that the Clift Quarry men were paid £1.6s per 100 feet for stone sent out and £1.4s in stock, starvation wages … it cannot be done for the money .. We have stone at our crane that was dug six months ago.[19] And there was still agitation for an 8-hour shift, which had James Milsom writing to the local newspaper in opposition to Sir John Dickson Poynder MP in 1894.[20]

The Box branch of the OSM ceased in 1912 and the union merged into the Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers (AUBTW) after the First World War. The AUBTW had a long existence in the village and in 1950 William George Case (17 April 1877-1955), a banker mason from Wadswick who later lived in the Devizes Road, was presented with a medal for 25-years-service as secretary of the local branch.[21] He had been a member for over 50 years.

In the next issue Jane recounts the stories of the Georgian stonemasons and their families who operated in Box.

There had been a close connection between employers and workers, such as Lewis and Brewer, the contractors excavating the eastern section of Box Tunnel, who had induced the men to contribute to a fund, from which the sick receive 1s a day and those who have met with accidents 1s.6d a day each... this plan has given general satisfaction to the men whose liberal wages enable them by a small sacrifice to provide.[13] The local ganger system, based on sons working for fathers, probably connected employers with workers and enforced a hierarchy in the trade.

There were further strikes by London masons. One in 1877 complained that the importation of foreign workmen continues.[14]

A local newspaper reported: the stone trade of Corsham and Box is in a very depressed state at present .. many of the freestone masons are out of work. They blamed The Masters’ Union who have decided to prohibit the introduction of worked stone into the large towns of the kingdom.[15] The reference to worked stone is interesting because it suggests that the skill premium of master masons in the local market was being threatened, possibly facilitated through the railways.

Unions in Box

These early unions consisted of skilled men who limited entry to their trades. They could be subcontractors or sometimes small employers, such as the gang system in Box quarries. The trade was highly stratified differentiating skilled (banker and journeymen) masons and unskilled (labourer and underground miner) members. Often with high income levels, some of these masons were able to save so it's not surprising that the Operatives Society started as a friendly society.

John Shell (25 Feb 1828 -1 February 1902) was the first foreman and later manager at Box Wharf, operated by the Pictor family for their Clift Quarry Works. He was the son of Robert (b 1801) and Sarah (b 1799) and grew up as part of a quarry family who lived at Box Quarries in 1841. He was admitted to the Box Lodge of the Operative Society of Masons and Quarrymen in 1857, paying one shilling contribution in 1858. He and his family were possibly members of the Plymouth Brethren at the Quarry Hill Chapel, which may have influenced his social conscience.[16] In 1881 he was recorded as Master mason (employs 7 men and 5 boys) whilst living at 3 Bridge Cottages (assumed to refer to Wharf Cottages). He died at Reading in 1902.[17]

Although there was no concerted effort by the Box quarrymen to strike, there were intermittent disruptions. One such was in 1876 when the Box Hill day men came out demanding an extra 2 shillings (10p) per week.[18] They were supported by the Bathford miners and threatened to bring 1,500 men out on strike. A ganger wrote an open letter in 1889 saying that the Clift Quarry men were paid £1.6s per 100 feet for stone sent out and £1.4s in stock, starvation wages … it cannot be done for the money .. We have stone at our crane that was dug six months ago.[19] And there was still agitation for an 8-hour shift, which had James Milsom writing to the local newspaper in opposition to Sir John Dickson Poynder MP in 1894.[20]

The Box branch of the OSM ceased in 1912 and the union merged into the Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers (AUBTW) after the First World War. The AUBTW had a long existence in the village and in 1950 William George Case (17 April 1877-1955), a banker mason from Wadswick who later lived in the Devizes Road, was presented with a medal for 25-years-service as secretary of the local branch.[21] He had been a member for over 50 years.

In the next issue Jane recounts the stories of the Georgian stonemasons and their families who operated in Box.

References

[1] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 November 1849 and London Evening Standard, 12 April 1839

[2] The Monmouthshire Merlin, 25 May 1839

[3] The Somerset County Gazette, 15 June 1839

[4] The Charter, 25 August 1839 and The Monmouthshire Beacon, 22 November 1839

[5] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 26 March 1840

[6] The Sun, 4 October 1841

[7] Bell’s New Weekly Messenger, 17 October 1841

[8] The Evening Mail, 16 August 1854

[9] Shipping and Mercantile Gazette, 25 August 1854

[10] London Evening Standard, 7 June 1860; The Weekly Dispatch, 10 June 1860; The Evening Mail, 24 September 1860

[11] The Morning Advertiser, 10 September 1859

[12] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 24 October 1861

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 November 1877

[15] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 3 March 1877

[16] Based on his son’s upbringing Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 May 1932

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 February 1902

[18] North Wilts Herald, 1 April 1876

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 23 November 1889

[20] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 May 1894

[21] The Wiltshire Times, 18 March 1950

[1] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 14 November 1849 and London Evening Standard, 12 April 1839

[2] The Monmouthshire Merlin, 25 May 1839

[3] The Somerset County Gazette, 15 June 1839

[4] The Charter, 25 August 1839 and The Monmouthshire Beacon, 22 November 1839

[5] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 26 March 1840

[6] The Sun, 4 October 1841

[7] Bell’s New Weekly Messenger, 17 October 1841

[8] The Evening Mail, 16 August 1854

[9] Shipping and Mercantile Gazette, 25 August 1854

[10] London Evening Standard, 7 June 1860; The Weekly Dispatch, 10 June 1860; The Evening Mail, 24 September 1860

[11] The Morning Advertiser, 10 September 1859

[12] Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, 24 October 1861

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 18 July 1839

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 November 1877

[15] Trowbridge and North Wilts Advertiser, 3 March 1877

[16] Based on his son’s upbringing Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 May 1932

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 February 1902

[18] North Wilts Herald, 1 April 1876

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 23 November 1889

[20] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 8 May 1894

[21] The Wiltshire Times, 18 March 1950