|

Arthur Courtenay Stewart

of Ashley Manor Alan Payne with Charles Freeman January 2022 The story of the Stewart family at Ashley Manor is a timepiece of British history as well as Box society. Arthur Stewart lived much of his life during the height of British imperial naval power, when Britain dominated the seas of the world, with Royal Naval bases and fuelling stations across the world from Hong Kong to Bermuda, from Gibraltar to Singapore, from Malta to Wei Hai Wei, from Cape Town to Vancouver, from India and Australia through to South Africa to Canada, and a host of places in between. His service to the country went from the age of sail to the Second World War. |

Arthur Courtenay Stewart CBE was born in May 1871 at Kensington, London, the fifth child of Charles Patrick Stewart and Frances Anne Cruttenden. His parents were extremely wealthy and, just before Arthur’s birth, they were living at 92 Lancaster Gate, London with four children and eleven servants. The family affluence allowed Arthur’s father to build a brand-new manor house at Silwood Park, Sunninghill as his family dynastic centre. The father was an unusual man, who has been described as: keen on horse racing and partying, and built his new house around a splendid ballroom where, on race days and holidays,

he would entertain the sons of Queen Victoria.[1]

he would entertain the sons of Queen Victoria.[1]

Naval Career

As a nine-year-old, Arthur was a boarder at Sudbury Hill School, Harrow-on-the-Hill, run by Edward Ridley Hastings. This was a preparatory school seen as a “feeder” to Harrow and it is still operating as a co-educational establishment under the name Orley Farm School. Arthur never got to Harrow, however, because his father died in 1882, and a different career beckoned when in 1884 his appointment as a Royal Navy Cadet aged 13 was published in the Army and Navy Gazette. He had come 18th out of 32 candidates in the exam.[2]

Arthur trained initially in the old wooden, line-of-battle ship, the Britannia, moored in the river Dart, long before the Naval College was built at Dartmouth. By 1887 he was a Midshipman at sea in the Mediterranean in HMS Superb. This was one of the curious ships built during the transition from sail to engine power. She had been constructed for the Ottoman Navy but was compulsorily purchased by the Royal Navy in 1878 due to a scare of war against Russia. Equipped with 3 masts and a coal fired engine, she did not perform well under either of these, and she lasted only a few years before advancing technology made her redundant.

As a Midshipman, Arthur undertook short specialist courses in Seamanship, Torpedo, Gunnery and Pilotage but classroom work does not seem to have been his strong point. The results were 3rd class pass, 3rd class, 2nd class and 3rd respectively. Service in other ships followed in rapid succession. This included a period on the China station (Britain at the time having bases at both Hong Kong and at Wei Hai Wei in north China). Arthur was a Midshipman in 1887, a Sub Lieutenant in 1891 and a Lieutenant in 1893, although his Captain in 1888 described the young Midshipman Stewart as “inattentive”. More happily, another Captain a couple of years later reported that Arthur was “zealous and capable”. In 1904 he was promoted to Commander and he went on to achieve the rank of Captain. His record of service (available online from the National Archives) has a long list of ships: after Superb came, among others, HM Ships Imperieuse, Northumberland, Hotspur, Northampton, Powerful, Russell, Queen, Exmouth and Cressy. Some of these names have passed down the generations to current or very recent ships. Much of his time was in the Mediterranean or on the China Station, but he served in what was then called the Channel Squadron too. In 1910 he was given further training at HMS Vernon for torpedoes and HMS Excellent for gunnery, both training establishments at Portsmouth.

In 1908 Arthur was the Executive Officer (ie the Second in Command) of the battleship HMS Exmouth in the Mediterranean Fleet, based at Malta. Ships of that size and at that time required vast amounts of manpower to shovel coal and handle the enormous guns, and Exmouth, with nearly 600 men onboard, was no exception. Just after Christmas that year Messina, and the surrounding area at the “toe” of Italy, was hit by the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Europe with a death toll of maybe 100,000 people. HMS Exmouth was one of 7 British warships which were part of the international rescue effort. Arthur’s “exceedingly able and energetic” work in this crisis was rewarded with the Italian decoration of Commander of the Crown of Italy, although it was not until 1910 that the award was made.

Despite the amount of sea service on Arthur’s record it does not seem to contain those words which have such magic for a Seaman Office, “In Command”. However, he was a gifted linguist and it was probably because of this in 1910 he was appointed naval attaché in Rome, adding the Italian language to the French which he already spoke to interpreter standard.[3]

As a nine-year-old, Arthur was a boarder at Sudbury Hill School, Harrow-on-the-Hill, run by Edward Ridley Hastings. This was a preparatory school seen as a “feeder” to Harrow and it is still operating as a co-educational establishment under the name Orley Farm School. Arthur never got to Harrow, however, because his father died in 1882, and a different career beckoned when in 1884 his appointment as a Royal Navy Cadet aged 13 was published in the Army and Navy Gazette. He had come 18th out of 32 candidates in the exam.[2]

Arthur trained initially in the old wooden, line-of-battle ship, the Britannia, moored in the river Dart, long before the Naval College was built at Dartmouth. By 1887 he was a Midshipman at sea in the Mediterranean in HMS Superb. This was one of the curious ships built during the transition from sail to engine power. She had been constructed for the Ottoman Navy but was compulsorily purchased by the Royal Navy in 1878 due to a scare of war against Russia. Equipped with 3 masts and a coal fired engine, she did not perform well under either of these, and she lasted only a few years before advancing technology made her redundant.

As a Midshipman, Arthur undertook short specialist courses in Seamanship, Torpedo, Gunnery and Pilotage but classroom work does not seem to have been his strong point. The results were 3rd class pass, 3rd class, 2nd class and 3rd respectively. Service in other ships followed in rapid succession. This included a period on the China station (Britain at the time having bases at both Hong Kong and at Wei Hai Wei in north China). Arthur was a Midshipman in 1887, a Sub Lieutenant in 1891 and a Lieutenant in 1893, although his Captain in 1888 described the young Midshipman Stewart as “inattentive”. More happily, another Captain a couple of years later reported that Arthur was “zealous and capable”. In 1904 he was promoted to Commander and he went on to achieve the rank of Captain. His record of service (available online from the National Archives) has a long list of ships: after Superb came, among others, HM Ships Imperieuse, Northumberland, Hotspur, Northampton, Powerful, Russell, Queen, Exmouth and Cressy. Some of these names have passed down the generations to current or very recent ships. Much of his time was in the Mediterranean or on the China Station, but he served in what was then called the Channel Squadron too. In 1910 he was given further training at HMS Vernon for torpedoes and HMS Excellent for gunnery, both training establishments at Portsmouth.

In 1908 Arthur was the Executive Officer (ie the Second in Command) of the battleship HMS Exmouth in the Mediterranean Fleet, based at Malta. Ships of that size and at that time required vast amounts of manpower to shovel coal and handle the enormous guns, and Exmouth, with nearly 600 men onboard, was no exception. Just after Christmas that year Messina, and the surrounding area at the “toe” of Italy, was hit by the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Europe with a death toll of maybe 100,000 people. HMS Exmouth was one of 7 British warships which were part of the international rescue effort. Arthur’s “exceedingly able and energetic” work in this crisis was rewarded with the Italian decoration of Commander of the Crown of Italy, although it was not until 1910 that the award was made.

Despite the amount of sea service on Arthur’s record it does not seem to contain those words which have such magic for a Seaman Office, “In Command”. However, he was a gifted linguist and it was probably because of this in 1910 he was appointed naval attaché in Rome, adding the Italian language to the French which he already spoke to interpreter standard.[3]

|

Marriage

It was shortly after his appointment in Rome that he met and a year later in 1911 married Gwendolyn Marion Story, an American heiress, born in Italy.[4] She was the daughter of the Thomas Waldo Story (known as Waldo), a sculptor, art critic, poet and book editor, who lived in Rome but had been educated at Eton and Oxford. The family had spent much time in England and Waldo moved in influential circles, designing the Fountain of Love at Cliveden House, the society home of the Astor family. Gwendolyn’s parents had divorced and she lived with her mother before she and Arthur married and went on honeymoon to St Moritz. This period was a dramatic time for them both. Arthur’s mother had died in 1910 leaving him an important portrait by Joshua Reynolds and Gwendolyn’s father remarried a year later to an opera singer shortly before his death in 1915.[5] Arthur retired from the Royal Navy in 1913, aged only 42 and, no doubt, the couple looked to settle down to their future life as young socialites. But all was interrupted by the First World War and Arthur was recalled in charge of naval transport arrangements at Bayonne and Brest, France. He then became King's Harbour Master at Moudros, Greece, which before his time had been the major base for the Gallipoli campaign. He was awarded the CBE for his war services. |

Coming to Box

With a young family to care for, the Stewarts wanted to return to England and they bought Ashley Manor in Box, the old home of George Wilbraham Northey, lord of the manor. The house had become surplus to their requirements after the death of George Wilbraham in 1906 and his wife Louisa in 1907, when their son George Edward had settled his family at Cheney Court. The Manor House had initially been rented by Rev Albert Victor Gregoire, rector of Ditteridge, and run as a boys’ boarding school. Rev Gregoire tried to move the school to Broadstairs, Kent, in April 1912 but had to keep paying the rent as the lease could not be terminated.[6] There is no detail of when the Stewarts bought the house but possibly after the death of Rev Edward William Northey, head of the family, in October 1914, and the death of Anson Northey in the early days of the war. It is likely that the Stewarts came to Box late in 1914.[7]

With a young family to care for, the Stewarts wanted to return to England and they bought Ashley Manor in Box, the old home of George Wilbraham Northey, lord of the manor. The house had become surplus to their requirements after the death of George Wilbraham in 1906 and his wife Louisa in 1907, when their son George Edward had settled his family at Cheney Court. The Manor House had initially been rented by Rev Albert Victor Gregoire, rector of Ditteridge, and run as a boys’ boarding school. Rev Gregoire tried to move the school to Broadstairs, Kent, in April 1912 but had to keep paying the rent as the lease could not be terminated.[6] There is no detail of when the Stewarts bought the house but possibly after the death of Rev Edward William Northey, head of the family, in October 1914, and the death of Anson Northey in the early days of the war. It is likely that the Stewarts came to Box late in 1914.[7]

The first record of the Stewart family at Ashley Manor was in May 1915 when Gwendolyn advertised for a child’s cart and harness.[8] Ivor Courtenay Stewart, their only son was born there in July 1916. The family settled into life at the Manor, advertising for more staff there in 1917 and for a housemaid to go with them to London in May that year and again in the winter of 1918-19.[9] They needed staff not only to maintain their lifestyle but because they kept ponies, donkeys, rabbits and goats in the grounds for their two children.[10] By 1919 the family were wintering away from the village, this time abroad.[11]

|

Life at Ashley Manor Gwendolyn didn’t involve herself greatly in village life but concentrated her efforts on animal breeding. She advertised for an egg incubator in 1920 but it was mainly the breeding of miniature pedigree Pekinese dogs that interested her. Meanwhile, Arthur bred and sold Wyandotte chickens.[12] Their life continued in much the same way during the inter-war years. At the 1934 Paignton Dog Show she bagged Five first prizes and two seconds with her two Pekinese dogs, Bumble Bee and Pegasus and her bitch Gem.[13] Their daughter, Fiammetta Maud Courtenay Stewart, also showed Pekinese dogs and won three second prizes with her bitch Corona at the 1938 Bristol Dog Show whilst Gwendolyn won two first prizes with Bimbo and Wee Bee.[14] In 1927 Arthur was involved in an unusual event, the voluntary liquidation of a German company, the Continental Trading Company Ltd, which had operated at Hildebrandstrasse, Berlin. It appears to be a family company because an Extraordinary General Meeting was held at Ashley Manor to confirm the arrangements.[15] Unfortunately, I have found no other information. |

In accordance with the custom of the time for upper class young ladies, in 1931 Fiammetta was Presented at Court by her Stewart cousin, the Countess of Galloway, and she travelled with another female cousin to Australia in 1932. The family counted as relations the remarkable Victor Cazalet, Member of Parliament for Chippenham who was a friend of Lloyd George, Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden as well as leaders throughout the world.

Wartime and After

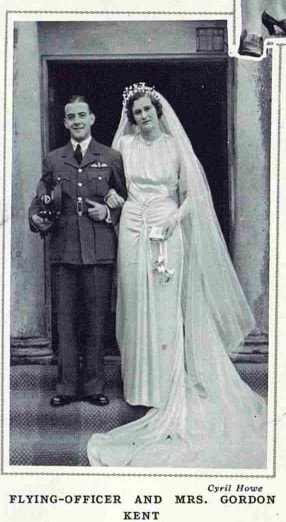

Arthur served his country again in the Second World War. By 1939 he was too old to be recalled for Naval duties but he was appointed a regional sub-controller by the Rural District Council in the Air Raid Protection service, and Fiammetta also volunteered for the ARP where she worked as a telephonist in the central wardens’ post. The census recorded twenty-three-year-old Ivor as a student seeking work. Fiammetta married shortly afterwards in October 1939 to Flying Officer Gordon Addison Hope Kent of Northallerton and they moved to Cirencester. Meanwhile, Arthur and Gwendolyn did their best to continue their lifestyle but by 1940 had reduced to employing only four maids.[16]

Arthur died 19 February 1958 leaving an estate of £15,509.19s.4d and Gwendolyn died in October 1961. Vicar Tom Selwyn-Smith wrote a charming piece describing her in the Parish Magazine of November 1961: Here was a character with roots in the last century and with the vitality, courage and strong will one associates with that age. There was something Roman about her, something of that select society which included artists amongst its palaces. After she had married the naval attaché from Britain she came to Ashley. It must have been a great contrast to her life in Italy. It was a joy to get her to talk about pictures, about Italy. Lately with her vast family of dogs, they were said to number forty at one time ... it will be hard to forget her.

Ivor Stewart never married and lived at Crofton, Ashley for some years until his death in Birmingham in 1975. Both Fiammetta and Gordon lived at Cirencester until their deaths in 1992.

Wartime and After

Arthur served his country again in the Second World War. By 1939 he was too old to be recalled for Naval duties but he was appointed a regional sub-controller by the Rural District Council in the Air Raid Protection service, and Fiammetta also volunteered for the ARP where she worked as a telephonist in the central wardens’ post. The census recorded twenty-three-year-old Ivor as a student seeking work. Fiammetta married shortly afterwards in October 1939 to Flying Officer Gordon Addison Hope Kent of Northallerton and they moved to Cirencester. Meanwhile, Arthur and Gwendolyn did their best to continue their lifestyle but by 1940 had reduced to employing only four maids.[16]

Arthur died 19 February 1958 leaving an estate of £15,509.19s.4d and Gwendolyn died in October 1961. Vicar Tom Selwyn-Smith wrote a charming piece describing her in the Parish Magazine of November 1961: Here was a character with roots in the last century and with the vitality, courage and strong will one associates with that age. There was something Roman about her, something of that select society which included artists amongst its palaces. After she had married the naval attaché from Britain she came to Ashley. It must have been a great contrast to her life in Italy. It was a joy to get her to talk about pictures, about Italy. Lately with her vast family of dogs, they were said to number forty at one time ... it will be hard to forget her.

Ivor Stewart never married and lived at Crofton, Ashley for some years until his death in Birmingham in 1975. Both Fiammetta and Gordon lived at Cirencester until their deaths in 1992.

Arthur and Gwendolyn Stewart lived in Box for over 40 years but they had a low profile, partly because they wintered away and also because they were very private people. But they were significant and their lives encompassed a world which has entirely vanished. They started in the great days of Royal Naval superiority and a world of international co-existence before the coming of the two World Wars. The First World War concluded with many military leaders buying grand properties in Box but the wealth and importance of military officers waned after 1945. If history teaches us anything, it must be that nothing is permanent and we should enjoy the brief moments of success, as evidenced by Arthur and Gwendolyn Stewart at Ashley Manor.

References

[1] Silwood Park - Past and Present | Visit | Imperial College London

[2] Army and Navy Gazette, 28 June 1884

[3] The Hampshire Telegraph, 16 April 1910

[4] Portsmouth Evening News, 20 January 1911

[5] London Daily News, 5 February 1910

[6] East Kent Times and Mail, 5 November 1913

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 October 1939

[8] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 22 May 1915

[9] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 5 May 1915 and 26 October 1918

[10] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 5 October 1918

[11] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 17 May 1919

[12] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 July 1920

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 28 July 1934

[14] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 5 November 1938

[15] The London Gazette, 23 September 1927

[16] East Kent Times and Mail, 12 October 1940

[1] Silwood Park - Past and Present | Visit | Imperial College London

[2] Army and Navy Gazette, 28 June 1884

[3] The Hampshire Telegraph, 16 April 1910

[4] Portsmouth Evening News, 20 January 1911

[5] London Daily News, 5 February 1910

[6] East Kent Times and Mail, 5 November 1913

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 7 October 1939

[8] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 22 May 1915

[9] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 5 May 1915 and 26 October 1918

[10] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 5 October 1918

[11] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 17 May 1919

[12] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 July 1920

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 28 July 1934

[14] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 5 November 1938

[15] The London Gazette, 23 September 1927

[16] East Kent Times and Mail, 12 October 1940