Society in Anglo-Saxon Box Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse August 2020

We get virtually no information about society in Anglo-Saxon England and nothing at all about the existence of ordinary people in Box in the years 600 to 800. This isn't surprising as most sources were written by residents of monastic institutions or concerned the lives of Saints. Perhaps the best we can do is to explore details included in the Law Codes published centuries later and preserved in monastic records and to chart the administrative structures that controlled people's lives.

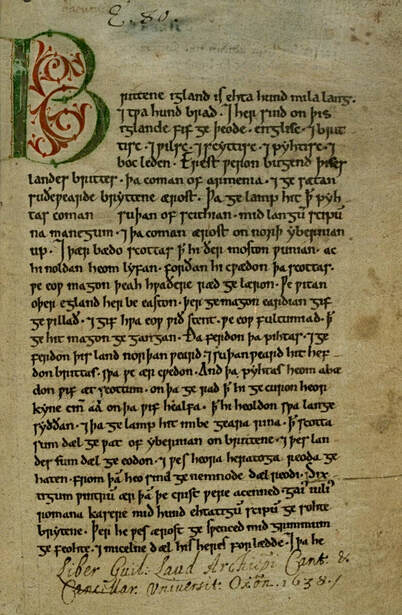

King Ine (688-726) set out a series of laws early in his reign which have been used to help us understand West Saxon society at that time. This document was one of four law-codes which have been preserved from the early medieval period, those of Æthelbert of Kent about 600, Hlothaere and Eadric of Kent about 680, Ine of Wessex about 690 and Wihtred of Kent about 695. Many of Ine’s laws are concerned with keeping the peace - punishment of disinheritance and for fighting in the king's house; restoration of property acquired by force without royal legal permission; death or payment of weregild (compensation to family for murder of family member) for thieves caught in the act.[1]

|

Ine’s Laws record the amounts of Feorm (food rents) required from every ten farmsteads: 10 vats honey, 300 loaves,

12 ambers (unit of capacity) of Welsh ale, 30 of clear ale, 2 full-grown cows or 10 wethers, 10 geese, 20 hens, 10 cheeses, an amber full of butter, 5 salmon, 20 pounds of fodder and 100 eels.[2] Such huge quantities were needed for royal visitations when the king, his court, royal servants, the witan (council of government), clerical and noble followers and officials came to visit. There are estimates that the total travellers would have been 220 people with 50 carts and over 200 animals.[3] Often the royal charge was feorm of one night, provisioning the royal visitors for one night only, and, when staying in lesser places, there were fractions of a full feorm recorded being required in Wiltshire.[4] Rise of Landed Aristocracy By the middle Saxon period, there was a change in administration and control of areas with the rise of appointed royal deputies. The family-tribal groupings were replaced by a more organised structure as Wessex expanded with local areas being controlled by sub-kings (subregulus), often royal family members. It has been said that: By c.650 it is likely that most of modern Wiltshire was divided between various West Saxon sub-kingdoms.[5] Land grants to Malmesbury Abbey in 670-680 by a man called Baldred have been deduced as evidence of a sub-kingdom based on Malmesbury or the surrounding area. |

Land grants were used as a response to the increasing demands of the king to support armies in the face of repeated Viking attacks. The social change was not linear and varied with the king taking back land under his own control and then gifting it to his preferred supporters sometimes with a titular rank of authority. These changes had far-reaching consequences. In the later West Saxon period, every man had a lord who interceded between him and the king.[6] Free peasants who owned land and performed duties to their lord in lieu of rent gradually became tied peasants, unable to leave their area, or in times of harvest failure, they fell lower into slavery. By the time of Alfred, the hundred and shire courts had increased in importance and Alfred’s Laws reflected that freemen had a duty to nobles, not directly to the king. By this time, the crown, nobility, churches and monasteries owned all landed estates and controlled the agricultural obligations of farm workers and slaves.

|

Anglo-Saxon Legal System England doesn't have a codified legal system derived from Roman law. Instead, our legal system comprises:

The administration of the law was managed by:

Most of the early Law Codes are statements of custom similar to Scandinavian codes until the Laws of Alfred tried to impose more central control. Without a police force, redress for misdemeanours had to be instigated by the victims. |

Evolution of Great Estates and Hundreds

The middle Saxon period (perhaps the 700s) saw the emergence of large estates covering several vills (farming communities).[7] It is likely that these estates were based on the old tribal regiones areas and, in turn, they spawned the medieval hundreds, the administration area of 100 hides. At the heart of the great estates was a caput (the home estate of a nobleman) or villa regalis (royal base). Often the estates had a central home farm run by a royal reeve, who controlled the local militia and certain laws, with varying degrees of control over outlying farms. Estates were often held by the king and various royal vills have been identified in our area at Calne, Warminster, Melksham, Westbury, Sherston, Chippenham and Bradford-on-Avon. Box Valley was on the periphery of an estate but would have been more suitable as an area used as a bread basket. Placenames of Kingsdown, Kingsdown Wood, Kingsdown Close, Kingsmoor Piece and Kingsmead may reflect royal influence during this period.[8] Box might have been an outlying farm, probably with considerable independence but owing goods and services to the caput and satisfying the usual requirements of the royal estates of bread, cheese, ale and meat.[9] |

By the year 700 much land was already held by a lord of the manor, who took over areas and provided army service, repaired bridges and paid taxes.[13] We can see something about the lives of ordinary people from Ine's Laws. Service in the fyrd (army) was an important part of the duty of free Saxons. Noblemen neglecting this were required to pay 120s and forfeit their land. Lesser freemen (ceorls) failing to perform military service were required to pay 30s as a fine. Duty of service and loyalty to kin groups were key parts of Saxon responsibilities. Leaving a lord's service without permission would incur a massive fine of 60s. Ceorls proved to have committed theft would have their hand or foot cut off. In return the families of dead ceorls would be supported with 6s a year and a cow in summer and an ox in winter, with the homestead supported by relatives until children had grown up.

By the time of King Edgar (957-975) the hundreds were a fully-established administrative system responsible for a huge range of social, legal and financial functions. According to the Hundred Ordinance issued by Edgar, responsibilities including bringing criminals to justice at the hundred court, which met every four weeks under the authority of the hundred-reeve.[10] The reeve was responsible for agriculture and personal services from a vaste range of people of different status. We can speculate about Box’s inhabitants, based on the Domesday Book, where there were more slaves and fewer freemen in Wessex than in other areas.[11] Specialist workers like ploughmen, millers, smiths and foresters often had slave status and this may have been the case in Box.[12] There is no middle Saxon evidence to determine which hundred region included Box. The story of Aldhelm’s discovery of building stone suggests a connection with Malmesbury but it was part of the Chippenham hundred in the Geld Rolls, bound in with the Exeter Domesday record after 1086.

By the time of King Edgar (957-975) the hundreds were a fully-established administrative system responsible for a huge range of social, legal and financial functions. According to the Hundred Ordinance issued by Edgar, responsibilities including bringing criminals to justice at the hundred court, which met every four weeks under the authority of the hundred-reeve.[10] The reeve was responsible for agriculture and personal services from a vaste range of people of different status. We can speculate about Box’s inhabitants, based on the Domesday Book, where there were more slaves and fewer freemen in Wessex than in other areas.[11] Specialist workers like ploughmen, millers, smiths and foresters often had slave status and this may have been the case in Box.[12] There is no middle Saxon evidence to determine which hundred region included Box. The story of Aldhelm’s discovery of building stone suggests a connection with Malmesbury but it was part of the Chippenham hundred in the Geld Rolls, bound in with the Exeter Domesday record after 1086.

Saxon Farming Methods

The evolution of a heavy Saxon plough has long been considered critical in the development of revolutionary farming methods which dominated medieval arable husbandry. This plough had an iron coulter to cut through the soil ahead of the plough share and is believed to have encouraged cultivation in long, narrow strips in large open fields, throwing up ridges and creating deep furrows with headlands where the plough needed to turn.

A much-quoted passage in Ine’s laws has often been claimed to indicate the development of this technology in the 600s. At face value this is the first reference to organisation of the common fields: If commoners have a common meadow or other -partible - land to fence, and some have fenced their portion and some have not [and cattle get in] and eat up their common crops or their grass, then those who are responsible for the opening shall go and pay compensation for the damage which has been done to the others, who have enclosed their portion ("getynednye").[14] The discovery of a seventh century coulter at Lyminge, Kent, in 2010 also seemed to confirm an early date.[15] However, it has been suggested that Ine's law describes a fence around an area of arable separating it from meadow held in common. In this event, the development of open fields probably took place over a long period of time, perhaps beginning around the time of Ine’s laws but coming into fruition later. This is discussed more fully in a later issue.

Conclusion

It is hard to see much happiness in the lives of early medieval residents in Box but that reflects the legalistic nature of the evidence which concentrated on sanctions for breaking the laws. There is little evidence of ordinary domestic and family life or of the celebrations which accompanied saints days in Christianised Wessex. What we do see is a desire that Anglo-Saxon people should be treated uniformly according to their status. However, this intention became less important in the face of repeated Viking attack, as we shall see in the next issue of the website.

The evolution of a heavy Saxon plough has long been considered critical in the development of revolutionary farming methods which dominated medieval arable husbandry. This plough had an iron coulter to cut through the soil ahead of the plough share and is believed to have encouraged cultivation in long, narrow strips in large open fields, throwing up ridges and creating deep furrows with headlands where the plough needed to turn.

A much-quoted passage in Ine’s laws has often been claimed to indicate the development of this technology in the 600s. At face value this is the first reference to organisation of the common fields: If commoners have a common meadow or other -partible - land to fence, and some have fenced their portion and some have not [and cattle get in] and eat up their common crops or their grass, then those who are responsible for the opening shall go and pay compensation for the damage which has been done to the others, who have enclosed their portion ("getynednye").[14] The discovery of a seventh century coulter at Lyminge, Kent, in 2010 also seemed to confirm an early date.[15] However, it has been suggested that Ine's law describes a fence around an area of arable separating it from meadow held in common. In this event, the development of open fields probably took place over a long period of time, perhaps beginning around the time of Ine’s laws but coming into fruition later. This is discussed more fully in a later issue.

Conclusion

It is hard to see much happiness in the lives of early medieval residents in Box but that reflects the legalistic nature of the evidence which concentrated on sanctions for breaking the laws. There is little evidence of ordinary domestic and family life or of the celebrations which accompanied saints days in Christianised Wessex. What we do see is a desire that Anglo-Saxon people should be treated uniformly according to their status. However, this intention became less important in the face of repeated Viking attack, as we shall see in the next issue of the website.

References

[1] http://historyofengland.typepad.com/documents_in_english_hist/2012/10/selected-laws-of-ine-688-695.html

[2] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.73

[3] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.130

[4] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.140

[5] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.100

[6] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.256

[7] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.105

[8] The Tithe Apportionment map references are Kings Down (615), Kingsdown Wood (425 & 763), Kingsdown Close (737 & 739), Kingsmoor Piece (426) and Kingsmead (292)

[9] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.77

[10] The hundreds in Wiltshire may have been of varying sizes, not specifically 100 hides

[11] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, 1955, p.256-7

[12] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, 1955, p.258

[13] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.14

[14] https://archive.org/stream/lawsofearliesten00grea#page/48/mode/2up. Translation quoted by David Hall, The Open Fields of England, 2014, Oxford University Press, p.172-73

[15] See https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-12997877

[1] http://historyofengland.typepad.com/documents_in_english_hist/2012/10/selected-laws-of-ine-688-695.html

[2] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, 1995, Leicester University Press, p.73

[3] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.130

[4] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.140

[5] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.100

[6] Barbara Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p.256

[7] Simon Andrew Draper, Landscape, settlement and society in Roman and early medieval Wiltshire, 2006, Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ p.105

[8] The Tithe Apportionment map references are Kings Down (615), Kingsdown Wood (425 & 763), Kingsdown Close (737 & 739), Kingsmoor Piece (426) and Kingsmead (292)

[9] Hannah Whittock and Martyn Whittock, The Anglo-Saxon Avon Valley Frontier: A River of Two Halves, 2014, Fontmill Media Limited, p.77

[10] The hundreds in Wiltshire may have been of varying sizes, not specifically 100 hides

[11] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, 1955, p.256-7

[12] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, 1955, p.258

[13] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol II, p.14

[14] https://archive.org/stream/lawsofearliesten00grea#page/48/mode/2up. Translation quoted by David Hall, The Open Fields of England, 2014, Oxford University Press, p.172-73

[15] See https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-12997877