Burlington Bunker (photo BBC Wilts)

Burlington Bunker (photo BBC Wilts)

Nuclear Threat at Rudloe

in 1950s and 1960s

David Ibberson & Alan Payne

January 2014

The terrifying story of atomic threat after the end of World War 2

The 1960s are often remembered as the period of the Swinging Sixties, the mini skirt, Peace and Love. The Beatles had number one hit records with Love Me Do, She Loves You and Can't Buy Me Love. Flower Power ruled, pop festivals started and many believe that this was an era that defined our modern world. But this is only half of the story in a world still haunted by the memory of war.

Perhaps the most bizarre twist in the whole history of Box came in 1963 when Box and Corsham were suddenly thrown into a spy scandal of international proportions at the centre of threatened nuclear war with the potential of an atomic bomb being dropped on the parish. Whilst this now seems incredible, at the time it was a very real possibility.

The news was broken by a group of anti-nuclear protestors called Spies for Peace who announced in April 1963 that Hawthorne was the headquarters of a series of emergency Regional Seats of Government in the event that Britain was under nuclear attack. People searched for this location but couldn't find it. In fact the name Hawthorne was adopted for a telephone exchange for all the military establishments on the west side of Corsham during World War 2. There never was a location with this name and its purpose was only to confuse the enemy.

The nuclear plan that had been developing since the 1950s was based on the premise of a guaranteed nuclear retaliation against any aggressors attacking Britain.[1] Under Corsham and Box a large number of government and military officials would shelter in a permanent citadel, safe underground from nuclear fallout.[2] With a codename Backbone, a communications network here was intended to enable government to continue and provide direct communication to regional centres throughout Britain.

Perhaps the most bizarre twist in the whole history of Box came in 1963 when Box and Corsham were suddenly thrown into a spy scandal of international proportions at the centre of threatened nuclear war with the potential of an atomic bomb being dropped on the parish. Whilst this now seems incredible, at the time it was a very real possibility.

The news was broken by a group of anti-nuclear protestors called Spies for Peace who announced in April 1963 that Hawthorne was the headquarters of a series of emergency Regional Seats of Government in the event that Britain was under nuclear attack. People searched for this location but couldn't find it. In fact the name Hawthorne was adopted for a telephone exchange for all the military establishments on the west side of Corsham during World War 2. There never was a location with this name and its purpose was only to confuse the enemy.

The nuclear plan that had been developing since the 1950s was based on the premise of a guaranteed nuclear retaliation against any aggressors attacking Britain.[1] Under Corsham and Box a large number of government and military officials would shelter in a permanent citadel, safe underground from nuclear fallout.[2] With a codename Backbone, a communications network here was intended to enable government to continue and provide direct communication to regional centres throughout Britain.

|

The Cold War

The 1950s and 1960s was a time of heightened tension between Russia and the west (the Cold War). The international political situation was tense: the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 was as close to a third World War as we have ever come; and the 1964 Peter Sellers' film Dr Strangelove depicted a nuclear fanatic who Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was a reflection of these concerns. |

Photo BBC Wilts

Photo BBC Wilts

What incensed the protestors most was that the government was seen as politically self serving and prepared to sacrifice the general population through inadequate civil defence.

In sharp contrast to the provision of security to officials was the government's advice to the general public in The Civil Defence Information Bulletins of 1964. This advised Duck and Cover techniques as they did in the USA: guidance on how to mitigate the initial effects of the heat and nuclear blast; and preparing a fallout room. The inadequacy of hiding beneath the kitchen table was obvious for all to see.

In sharp contrast to the provision of security to officials was the government's advice to the general public in The Civil Defence Information Bulletins of 1964. This advised Duck and Cover techniques as they did in the USA: guidance on how to mitigate the initial effects of the heat and nuclear blast; and preparing a fallout room. The inadequacy of hiding beneath the kitchen table was obvious for all to see.

The revelations led to tens of thousands of people attending the Aldermaston march of 1963 to support the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The government started a cover-up, banning the BBC film The War Game in 1965. The Protect and Survive leaflets of the 1970s and 1980s, however, openly stated that there would be no public shelter. Meanwhile the whole project was surrounded in government secrecy under the pseudonym Rudloe Manor, the new name of the Hawthorne location.

Nuclear Headquarters Built at RAF Rudloe Manor

The Rudloe Manor site was selected as a shelter because at 100 feet below ground it could withstand all but a direct nuclear attack.[3] It had a central Operations Control Room and rooms called The Burlington Bunker would be the seat of national government to run the country after an initial enemy nuclear strike. Burlington would shelter military staff to conduct the war, deal with foreign relations and trade delegations, and be in control of national shipping and ports.[4] It also had a function to assist regional recovery after a nuclear strike with staff for Departments of Energy, Transport, the Environment and law enforcement through the Home Office.

Nuclear Headquarters Built at RAF Rudloe Manor

The Rudloe Manor site was selected as a shelter because at 100 feet below ground it could withstand all but a direct nuclear attack.[3] It had a central Operations Control Room and rooms called The Burlington Bunker would be the seat of national government to run the country after an initial enemy nuclear strike. Burlington would shelter military staff to conduct the war, deal with foreign relations and trade delegations, and be in control of national shipping and ports.[4] It also had a function to assist regional recovery after a nuclear strike with staff for Departments of Energy, Transport, the Environment and law enforcement through the Home Office.

Escalator entrance

Escalator entrance

Its purpose was to retaliate against enemy strikes but, even more sinister, was the possibility of a pre-emptive strike if it was feared that the enemy could destroy command and control centres in UK, particularly if Whitehall should be knocked out before transfer of control had been achieved. [5]

The site had a permanent staff of 600 RAF personnel. Underground tunnels were accessed through Westwells Road, sign posted as a Property Services Agency Supplies Division Depot, the only warehouse with a permanent Red Alert status.[6] At Fiveways, Rudloe, a Post Office microwave communications tower was built directly over the underground tunnels to provide headquarters with information from a network of subsidiary stations throughout UK. Sandbags marked the site of machine gun posts.

The site had a permanent staff of 600 RAF personnel. Underground tunnels were accessed through Westwells Road, sign posted as a Property Services Agency Supplies Division Depot, the only warehouse with a permanent Red Alert status.[6] At Fiveways, Rudloe, a Post Office microwave communications tower was built directly over the underground tunnels to provide headquarters with information from a network of subsidiary stations throughout UK. Sandbags marked the site of machine gun posts.

The complex was designed to house a massive number of government staff (some reports state up to twenty thousand people) with security and survival capacity for several months.[7] It was well stocked with food and clothing, provisions being close to RAF and Royal Navy Supplies Depots at Copenacre, Monks Park and HMS Royal Arthur. Special precautions were made for air and water which were purified to remove radioactive dust before going into the underground rooms.

The tower was only dismantled in 1995 and the base of it still remains as a grim reminder of this episode in Box's history.[8] But it would all have been very different if the cold war had turned to action.

The tower was only dismantled in 1995 and the base of it still remains as a grim reminder of this episode in Box's history.[8] But it would all have been very different if the cold war had turned to action.

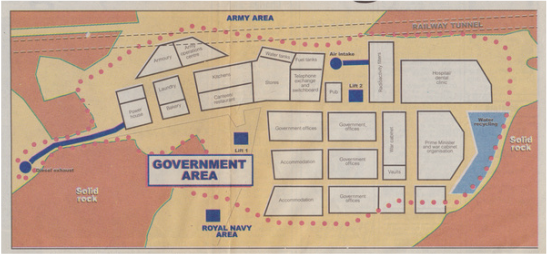

Plan of Burlington Bunker (Bath Chronicle 7 January 1999)

Plan of Burlington Bunker (Bath Chronicle 7 January 1999)

Burlington Bunker

The bunker was described in 2005 as: Inside it is like stepping back 50 years. Hundreds of swivel chairs delivered in 1959 are still unpacked. There are boxes of government-issue glass ashtrays, lavatory brushes and civil service tea sets.(9)

David Ibberson is one of the few local people who have seen inside the bunker. He gives an insight into life sheltering from radiation if nuclear war had broken out. Here is his report:

In the first decade of this century I had the opportunity to visit the more interesting parts of the now infamous Burlington Bunker, a once Top Secret location to accommodate the Government in the event of a nuclear strike. Those readers familiar with Whitehall and other areas of government may, on entering the bunker, have been surprised that there was no sign of oak panelled offices or luxurious office chairs, for make no mistake, you are clearly in a quarry. This view was reinforced by the insistence that we wore hard hats.

The walls left after stone extractions were still clearly visible although painted white and in some areas covered by panels. The floors had been built up and made into roadways to allow free passage of people and essential materials. Rooms had been fashioned using the areas hewn out by generations of quarrymen, and where this was not possible, rigid panels were used or good old fashioned bricks and cement. The area of the bunker is fairly vast so movement, for myself and other visitors was on an electric truck which took us to areas of interest.

First call was at the stationery store. Remember the bunker ceased to be maintained after 1992; this was the dawn of the computer age and government officials still conducted their business using paper and manual typewriters, hence, a good supply was needed. The stationery store did not disappoint: racks of paper, file covers, carbon paper and other essential office material. In those days every desk had four trays: in, out, pending and ash (since it was assumed the majority of officials smoked). Much of the contents of the store were still wrapped in brown paper and had remained in that state for decades.

The bunker was described in 2005 as: Inside it is like stepping back 50 years. Hundreds of swivel chairs delivered in 1959 are still unpacked. There are boxes of government-issue glass ashtrays, lavatory brushes and civil service tea sets.(9)

David Ibberson is one of the few local people who have seen inside the bunker. He gives an insight into life sheltering from radiation if nuclear war had broken out. Here is his report:

In the first decade of this century I had the opportunity to visit the more interesting parts of the now infamous Burlington Bunker, a once Top Secret location to accommodate the Government in the event of a nuclear strike. Those readers familiar with Whitehall and other areas of government may, on entering the bunker, have been surprised that there was no sign of oak panelled offices or luxurious office chairs, for make no mistake, you are clearly in a quarry. This view was reinforced by the insistence that we wore hard hats.

The walls left after stone extractions were still clearly visible although painted white and in some areas covered by panels. The floors had been built up and made into roadways to allow free passage of people and essential materials. Rooms had been fashioned using the areas hewn out by generations of quarrymen, and where this was not possible, rigid panels were used or good old fashioned bricks and cement. The area of the bunker is fairly vast so movement, for myself and other visitors was on an electric truck which took us to areas of interest.

First call was at the stationery store. Remember the bunker ceased to be maintained after 1992; this was the dawn of the computer age and government officials still conducted their business using paper and manual typewriters, hence, a good supply was needed. The stationery store did not disappoint: racks of paper, file covers, carbon paper and other essential office material. In those days every desk had four trays: in, out, pending and ash (since it was assumed the majority of officials smoked). Much of the contents of the store were still wrapped in brown paper and had remained in that state for decades.

Photo BBC Wilts

Photo BBC Wilts

Telephones, as today were an essential office tool, of course, hard wired and analogue. The bunker has a fully equipped telephone exchange from the pre-trunk dialling days when if you wished to make a call you dialled ‘0’ to connect to an operator.

There still remains rows of seats and desks (with modesty boards) with banks of sockets through which operators would route calls. Of course you might not know the number and had to speak to a supervisor who was equipped with telephone directories for the whole of the UK. These were updated each year.

There still remains rows of seats and desks (with modesty boards) with banks of sockets through which operators would route calls. Of course you might not know the number and had to speak to a supervisor who was equipped with telephone directories for the whole of the UK. These were updated each year.

Documents had to be distributed around the bunker complex. Most large establishments would have staff known as messengers. They would collect and deliver papers and documents from offices for distribution. Whilst no doubt such staff would have been employed in the bunker, they had a fast track method. From a central registry, papers could be distributed throughout the complex using vacuum tubes similar to those found in many departmental stores of the day where money was taken from customers, despatched to a cashier, who would then return any change due through the same tubes.

We also visited the library. The library was not designed to entertain, but provide information, the BMA lists of practising doctors being one example, but I was puzzled as to why a book on the sexual habits of various African tribes should be available, someone no doubt knew. Much of the contents were academic, perhaps this was the entertainment! When I visited, the library appeared much depleted of material, I suspect much of it was classified and would have been removed or secured in a safe place.

We also visited the library. The library was not designed to entertain, but provide information, the BMA lists of practising doctors being one example, but I was puzzled as to why a book on the sexual habits of various African tribes should be available, someone no doubt knew. Much of the contents were academic, perhaps this was the entertainment! When I visited, the library appeared much depleted of material, I suspect much of it was classified and would have been removed or secured in a safe place.

|

Surviving Nuclear Fallout

Visiting the kitchen area was possibly the most enlightening. Ovens, boilers, mixers of an industrial size and many other kitchen essentials were there, installed but never used. Plates, cups, saucers, stacked tables and chairs, in fact everything needed to sustain several thousand people. |

Keep Head Covered to Avoid Nuclear Fall-Out |

Of course, the occupants of the bunker might need medical support and to that end a hospital area was created. I would hesitate to call it a hospital, a hospital ward, yes, with bed pans, sluices and rather primitive beds that any ex-serviceman of the period would recognise. No sign of modern hospital technology.

The above is only a sample of the areas used to accommodate staff: living quarters, recreational areas, wash and toilet facilities, meeting rooms were all there ready to spring into life. Be you Prime Minister or humble civil servant, living in the bunker would have been challenging.

The Burlington Bunker that I visited may by now have been sealed and returned to nature as other quarries once used by the MOD have. However, make no mistake, being housed underground for months on end would not have been pleasant and I suspect that had the facility been used, many would say I wish I had taken my chances above the ground rather than be entombed in the hillside at Box.

Postscript

After visiting the Bunker we were taken outside of its boundary to see the area where miners were working just before World War 2. This was a damp, murky area virtually untouched since the miners (quarrymen) left, their tools dropped where they last worked when the quarries were requisitioned for war work. Here was a time capsule dated 1939 or thereabouts. Will the Burlington become another time capsule for future generations to visit, who can tell?

If you want to read more about this period there is a marvellous and detailed report at:

http://corsham.thehumanjourney.net/pdfs/CORSHAM_report.pdf

References

[1] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.244

[2] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.244-6 estimated 20,000 personnel; Lt Cdr Dee Cleary, Corsham Tunnels, 2006, DCSA suggested 4,000.

[3] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK,1982, Burnet Books Ltd, p.119-123, 242, 264

[4] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.141, 277

[5] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.141,307

[6] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.270

[7] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.273

[8] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.271

[9] The Sunday Times, 30 October 2005,

The above is only a sample of the areas used to accommodate staff: living quarters, recreational areas, wash and toilet facilities, meeting rooms were all there ready to spring into life. Be you Prime Minister or humble civil servant, living in the bunker would have been challenging.

The Burlington Bunker that I visited may by now have been sealed and returned to nature as other quarries once used by the MOD have. However, make no mistake, being housed underground for months on end would not have been pleasant and I suspect that had the facility been used, many would say I wish I had taken my chances above the ground rather than be entombed in the hillside at Box.

Postscript

After visiting the Bunker we were taken outside of its boundary to see the area where miners were working just before World War 2. This was a damp, murky area virtually untouched since the miners (quarrymen) left, their tools dropped where they last worked when the quarries were requisitioned for war work. Here was a time capsule dated 1939 or thereabouts. Will the Burlington become another time capsule for future generations to visit, who can tell?

If you want to read more about this period there is a marvellous and detailed report at:

http://corsham.thehumanjourney.net/pdfs/CORSHAM_report.pdf

References

[1] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, 1998, Lee Cooper, p.244

[2] NJ McCamley, Secret Underground Cities, p.244-6 estimated 20,000 personnel; Lt Cdr Dee Cleary, Corsham Tunnels, 2006, DCSA suggested 4,000.

[3] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK,1982, Burnet Books Ltd, p.119-123, 242, 264

[4] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.141, 277

[5] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.141,307

[6] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.270

[7] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.273

[8] Duncan Campbell, War Plan UK, p.271

[9] The Sunday Times, 30 October 2005,