Rowe Family of Wadswick and the Indian Mutiny Stuart Rowe

Unless stated otherwise pictures courtesy George Rowe January 2019

Unless stated otherwise pictures courtesy George Rowe January 2019

There is a pleasant article in the 1897 Parish Magazine about the Rowe family who farmed at Wadswick. The report tells of the Sunday School outing, which included children from Wadswick arriving by Mr Rowe’s wagon which presented "a gay appearance, being decorated with flowers and the children waved their banners high".[1]

The Rowe family lived at Wadswick from 1891 until 1912. Their descendant, Stuart Rowe, came to visit Box and took us through their intriguing story which included a connection with the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and their later story which involves dire financial straits and an asylum. A fascinating part of Box's history.

The Rowe family lived at Wadswick from 1891 until 1912. Their descendant, Stuart Rowe, came to visit Box and took us through their intriguing story which included a connection with the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and their later story which involves dire financial straits and an asylum. A fascinating part of Box's history.

|

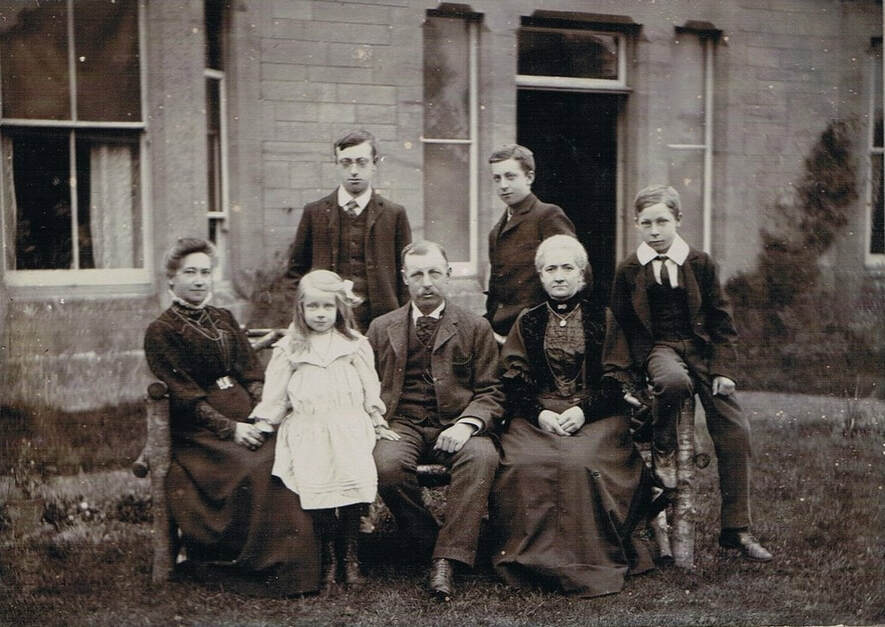

Frederick and Charlotte Rowe

My great grandparents, Frederick and Charlotte Rowe (nee Spokes), originally came from Stewkley, Buckinghamshire and Great Milton, Oxfordshire, respectively. It's always been a mystery why they moved to Wiltshire but we know that they were living in Box between 1891 and about 1912. In the censuses, their home was called Wadswick Farm but there are doubts about this as the Electoral Registers of 1893 to 1912 refer to their dwelling house as Bailey's Farm (presumably a misspelling of Bailiff's Farm), Wadswick. Frederick was active in supporting the Sunday School outings from Chapel Plaister children to join with St Thomas à Becket families. In 1903 he cleaned out his hay-making wagon to convey children to Shockerwick House.[2] It was a disaster. In rushing down to Box at 1.45pm, the driver turned too sharply and all the occupants were thrown out. Though greatly frightened, beyond slight bruises and cuts, no harm was done. My great grandfather clearly had aspirations for his own children, all of whom went to King Edwards School, Bath, rather than the local school in Box. Where was the daughter Maisie educated? When going to school and later as a youth, my grandfather used to ride a horse across the fields to get the train from Corsham. |

Thomas Edward Rowe, 1897-1981

My grandfather Thomas Edward Rowe was born in Wadswick in 1897, the youngest of three brothers with a younger sister born in 1902. In 1912 they left Box and moved to Cowley Lodge Farm, Preston Bissett, Buckinghamshire. Family anecdotes have it that the whole family moved lock stock and barrel and rented two trains to transport all the livestock and machinery plus a well-stocked library, furniture, paintings and musical instruments. They rented Cowley Lodge Farm for a few years and bought it in 1919. It's always been a mystery why they moved to Box and how they managed to buy Cowley Lodge. They were from poor families and had rented Bailiff’s Farm, Wadswick but suddenly money arrived from somewhere unknown to later generations of the family.

My grandfather Thomas Edward Rowe was born in Wadswick in 1897, the youngest of three brothers with a younger sister born in 1902. In 1912 they left Box and moved to Cowley Lodge Farm, Preston Bissett, Buckinghamshire. Family anecdotes have it that the whole family moved lock stock and barrel and rented two trains to transport all the livestock and machinery plus a well-stocked library, furniture, paintings and musical instruments. They rented Cowley Lodge Farm for a few years and bought it in 1919. It's always been a mystery why they moved to Box and how they managed to buy Cowley Lodge. They were from poor families and had rented Bailiff’s Farm, Wadswick but suddenly money arrived from somewhere unknown to later generations of the family.

I have discovered a fascinating connection with Box which might be relevant to the money, involving the Thornhill family. The point of connection between the Rowes and the Thornhills was through Charlotte Rowe’s sister, Martha Spokes, born in 1852. Martha was living with Frederick and Charlotte at Wadswick in 1911 and she is seen second right in the headline photo. For thirty years previously, she had been a servant to Mary Ellen (sometimes called Elizabeth) Birkett, from the Rectory, Haseley, Great Milton. At this point in the story we need to make a diversion to trace the story of the Thornhills.

Thornhill Family

Mary Birkett was Mark Bensley Thornhill’s second wife. His first wife was Anna Maria Farrell Kirke who he married in 1852 when he was 30 and she was 19. Anna appears to have died in 1867 and he married Mary Elizabeth Birkett, aged 49, in 1872. Mark was then 45 and Mary was of a roughly equivalent social status, the Birkett family being comfortably wealthy.

Presumably to introduce his new wife to his friends and Bath society, Mark took the tenancy of Sunnyside House, Box in the 1870s. Martha Spokes, then aged 22, came with them. Mark Thornhill was listed as private resident of Box in 1875.[3] But we know that the family were there a couple of years earlier because Henrietta Thornhill, orphaned niece of Mark who recurs later in the story, kept a daily diary recording family visits to Sunnyside:[4]

27 July 1874 Henrietta leaves to stay with Uncle Mark & Aunt Minna at Sunnyside, Box.

14 September 1874 Aunt Jones returns from a stay at Sunnyside with Uncle Mark (Thornhill). Aunt Minna writes to tell Henrietta that she may not go (to Sunnyside) until the Monday.

28 September 1874 Henrietta leaves to stay Uncle Mark (Thornhill) & Aunt Minna at Sunnyside, Box.

Mark died on 14 March 1900 on the Isle of Wight. In May of that year Mary presented one of her family’s painting to the newly-opened Victorian Art Gallery, Bath. It was Ecce Homo by Titian and the provenance of the painting was certified: This painting by Titian was in the collection of Hall Standish, Esq, and was given by him to Rev Thomas Birkett.[5] Mary Thornhill died in December 1901 and was buried in the family tomb at Bathwick Cemetery.[6] There is another fascinating twist to the early background of the Thornhills, not at Sunnyside but in India.

Indian Mutiny, 1857

Mark Bensley Thornhill was an Indian Army Officer and later Administrator in Bengal. Mark’s family had a long tradition in India, running the East India Trading Company and the family became extremely rich and quite famous. The story of the British in India at this time shows some of the worst aspects of Imperial mentality. The Thornhill family were involved in the Indian Mutiny (sometimes called the First War of Independence) in 1857 and have been the subject of various books and diaries. Mark was himself an author and a Justice of the Peace.[7]

The origins of the Mutiny started with signs of unrest and the mysterious appearance of chapatis (unleavened flatbread) in the offices of British officials. In February 1857 Mark Thornhill, uncle of Box's Mark and a magistrate in a small Indian town near the Taj Mahal in north India, came into his office to find four dirty little cakes of the coarsest flour, about the size and thickness of a biscuit lying on his desk. Batches of this home-made bread was soon seen throughout the area, which the British administrators understood to be a secret signal understood only by the native population. Wild rumours abounded throughout the sub-continent, including that the British had infiltrated the bullets of their new Enfield rifles with pig and cow fat and that the bread was a symbol of rebellion.

In April 1857 a revolt broke out in the village of Meerut, close to the Thornhill administration. A contemporary diary recorded the next events as:

12 June 1857 It was a fearfully hot day, and the (infantry) men were quite exhausted after marching eight miles. The artillery opened fire at a long distance, and the cavalry, led by Captain Forbes and Lieutenant Hutchinson of the engineers, charged and took some prisoners ... Mr Thornhill was slightly wounded, two Sikhs killed, and a few wounded.

26 September A sortie was made by our garrison to-day, and four guns taken. Mr Thornhill, Civil Service, volunteered to go out with a force to bring in the wounded... Poor fellow! he reached them all right by a safe road, but for some unknown reason returned by a different one through the most frequented streets, which had been loopholed by the enemy... The dhoolie-bearers could not stand the fire which was opened upon them. The escort was overwhelmed and Mr Thornhill himself badly wounded, but he managed to get into the Residency.

12 October Mr. Thornhill (Mark’s brother) died to-day from his wounds; he had not been married a year.

The reprisal of the British administration was excessive. Scottish Highlanders charged unarmed local people, innocent bystanders were flogged, humiliated and summarily hanged. It was a defining moment in Anglo-Indian relations. The failure of British government to react proportionately led to the breakdown of trust and communication between the British and Indian people which ultimately intensified demands for the separation of the countries. Unlike his two brothers who were also serving in India in 1857, our Mark survived the slaughter by posing as a Muslim woman during his escape. For Henrietta Thornhill, the author of the Sunnyside diary referred to earlier, the death of her parents, Robert & Mary, was a personal tragedy leaving her an orphan and dependent on the goodwill of other family members, like her uncle Mark.[8]

Mary Birkett was Mark Bensley Thornhill’s second wife. His first wife was Anna Maria Farrell Kirke who he married in 1852 when he was 30 and she was 19. Anna appears to have died in 1867 and he married Mary Elizabeth Birkett, aged 49, in 1872. Mark was then 45 and Mary was of a roughly equivalent social status, the Birkett family being comfortably wealthy.

Presumably to introduce his new wife to his friends and Bath society, Mark took the tenancy of Sunnyside House, Box in the 1870s. Martha Spokes, then aged 22, came with them. Mark Thornhill was listed as private resident of Box in 1875.[3] But we know that the family were there a couple of years earlier because Henrietta Thornhill, orphaned niece of Mark who recurs later in the story, kept a daily diary recording family visits to Sunnyside:[4]

27 July 1874 Henrietta leaves to stay with Uncle Mark & Aunt Minna at Sunnyside, Box.

14 September 1874 Aunt Jones returns from a stay at Sunnyside with Uncle Mark (Thornhill). Aunt Minna writes to tell Henrietta that she may not go (to Sunnyside) until the Monday.

28 September 1874 Henrietta leaves to stay Uncle Mark (Thornhill) & Aunt Minna at Sunnyside, Box.

Mark died on 14 March 1900 on the Isle of Wight. In May of that year Mary presented one of her family’s painting to the newly-opened Victorian Art Gallery, Bath. It was Ecce Homo by Titian and the provenance of the painting was certified: This painting by Titian was in the collection of Hall Standish, Esq, and was given by him to Rev Thomas Birkett.[5] Mary Thornhill died in December 1901 and was buried in the family tomb at Bathwick Cemetery.[6] There is another fascinating twist to the early background of the Thornhills, not at Sunnyside but in India.

Indian Mutiny, 1857

Mark Bensley Thornhill was an Indian Army Officer and later Administrator in Bengal. Mark’s family had a long tradition in India, running the East India Trading Company and the family became extremely rich and quite famous. The story of the British in India at this time shows some of the worst aspects of Imperial mentality. The Thornhill family were involved in the Indian Mutiny (sometimes called the First War of Independence) in 1857 and have been the subject of various books and diaries. Mark was himself an author and a Justice of the Peace.[7]

The origins of the Mutiny started with signs of unrest and the mysterious appearance of chapatis (unleavened flatbread) in the offices of British officials. In February 1857 Mark Thornhill, uncle of Box's Mark and a magistrate in a small Indian town near the Taj Mahal in north India, came into his office to find four dirty little cakes of the coarsest flour, about the size and thickness of a biscuit lying on his desk. Batches of this home-made bread was soon seen throughout the area, which the British administrators understood to be a secret signal understood only by the native population. Wild rumours abounded throughout the sub-continent, including that the British had infiltrated the bullets of their new Enfield rifles with pig and cow fat and that the bread was a symbol of rebellion.

In April 1857 a revolt broke out in the village of Meerut, close to the Thornhill administration. A contemporary diary recorded the next events as:

12 June 1857 It was a fearfully hot day, and the (infantry) men were quite exhausted after marching eight miles. The artillery opened fire at a long distance, and the cavalry, led by Captain Forbes and Lieutenant Hutchinson of the engineers, charged and took some prisoners ... Mr Thornhill was slightly wounded, two Sikhs killed, and a few wounded.

26 September A sortie was made by our garrison to-day, and four guns taken. Mr Thornhill, Civil Service, volunteered to go out with a force to bring in the wounded... Poor fellow! he reached them all right by a safe road, but for some unknown reason returned by a different one through the most frequented streets, which had been loopholed by the enemy... The dhoolie-bearers could not stand the fire which was opened upon them. The escort was overwhelmed and Mr Thornhill himself badly wounded, but he managed to get into the Residency.

12 October Mr. Thornhill (Mark’s brother) died to-day from his wounds; he had not been married a year.

The reprisal of the British administration was excessive. Scottish Highlanders charged unarmed local people, innocent bystanders were flogged, humiliated and summarily hanged. It was a defining moment in Anglo-Indian relations. The failure of British government to react proportionately led to the breakdown of trust and communication between the British and Indian people which ultimately intensified demands for the separation of the countries. Unlike his two brothers who were also serving in India in 1857, our Mark survived the slaughter by posing as a Muslim woman during his escape. For Henrietta Thornhill, the author of the Sunnyside diary referred to earlier, the death of her parents, Robert & Mary, was a personal tragedy leaving her an orphan and dependent on the goodwill of other family members, like her uncle Mark.[8]

Above left: British view of the rebellion and Above right: Indian view of the reprisals by Scottish Highlanders (both courtesy Smithsonianmag.com)

Later Family

It would seem that other Spokes family members also worked for the Thornhills in the 1880s. They were all living in Blandford Forum in 1881. So somehow the two families became connected. Then Frederick Rowe appeared on the scene, married Charlotte and they started farming at Wadswick. I can only surmise that the Thornhills left Martha or Charlotte some money around the turn of the century and that this was the source of their wealth. There are some portraits at my parents’ home that are possibly of the Thornhill family. It’s all a very intriguing mystery.

There are another couple of twists to the tale. The Rowe family’s money ran out in the 1920s - 30s. Cowley Lodge Farm was sold (but bought back later). My aunt Maisie (Mary Charlotte Rowe), who was born in Box, sadly, spent the last thirty years of her life from 1933 as a patient in Stone Mental Asylum, Buckinghamshire, until her death in 1961. No-one seems to know what happened. Another mystery.

It would seem that other Spokes family members also worked for the Thornhills in the 1880s. They were all living in Blandford Forum in 1881. So somehow the two families became connected. Then Frederick Rowe appeared on the scene, married Charlotte and they started farming at Wadswick. I can only surmise that the Thornhills left Martha or Charlotte some money around the turn of the century and that this was the source of their wealth. There are some portraits at my parents’ home that are possibly of the Thornhill family. It’s all a very intriguing mystery.

There are another couple of twists to the tale. The Rowe family’s money ran out in the 1920s - 30s. Cowley Lodge Farm was sold (but bought back later). My aunt Maisie (Mary Charlotte Rowe), who was born in Box, sadly, spent the last thirty years of her life from 1933 as a patient in Stone Mental Asylum, Buckinghamshire, until her death in 1961. No-one seems to know what happened. Another mystery.

|

Family Tree

Great Great grandmother Mary Rowe, nee Towfield (1822-1901), widow, was living at the High Street, Stewkley in 1871 and trading as a Corn Dealer. She was still there 10 years later with two sons and a domestic servant, a cook. Children: Ann (b 1853) Thomas (b 1857), carpenter; Sarah (b 1859); Frederick (1863 - 1933), my great grandfather, a labourer in 1881. Great grandfather Frederick (b 1863 in Stewkley - 1933) married in 1891 to Charlotte Spokes (b 1861 in Great Milton, Oxfordshire). They lived at Bailiff Farm between at least 1891 and 1911, often with other family members. Children: John (known as Jack) Frederick (b 17 May 1891, d in 1960s); George William (b 3 March 1893, d in 1980s at Melksham); Thomas Edward (14 March 1897 - 1981), my grandfather, born at Bailiff Farm; Mary Charlotte (known as Maisie) (29 January 1902 - 1961) My father Thomas Frederick George (always known as George) was born in 1927 and is still alive. My two brothers and I grew up in Preston Bissett, Buckinghamshire, where I was born in 1963. |

References

[1] Parish Magazine, 1897

[2] Parish Magazine, August 1903

[3] Kelly’s Directory

[4] http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/inglis/lucknow/lucknow.html

[5] Clifton Society, 31 May 1900

[6] Clifton Society, 2 January 1902

[7] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pass-it-on-the-secret-that-preceded-the-indian-rebellion-of-1857-105066360/

[8] http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/history/files/2012/05/Indian-Mutiny-500x363.jpg and https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pass-it-on-the-secret-that-preceded-the-indian-rebellion-of-1857-105066360/#0FpHfGzYAo8tf9XZ.99

[1] Parish Magazine, 1897

[2] Parish Magazine, August 1903

[3] Kelly’s Directory

[4] http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/inglis/lucknow/lucknow.html

[5] Clifton Society, 31 May 1900

[6] Clifton Society, 2 January 1902

[7] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pass-it-on-the-secret-that-preceded-the-indian-rebellion-of-1857-105066360/

[8] http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/history/files/2012/05/Indian-Mutiny-500x363.jpg and https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pass-it-on-the-secret-that-preceded-the-indian-rebellion-of-1857-105066360/#0FpHfGzYAo8tf9XZ.99