Saxon and Viking Routes in Box Alan Payne and Jonathan Parkhouse, December 2020

In this article we look at the visible evidence of the occupation of the area in Saxon and Viking periods, including trackways, houses, rivers and field structure. It is obvious that every site of habitation needed access as did fields and river launching points and a myriad of tracks existed for a multitude of purposes. We shouldn’t think of these as fixed routes but rather pathways used for specific purposes until the reason was lost and the track became overgrown again.

Regional Trackways

The Roman road on the southern boundary has been used over long periods and it is possible that the Viking Sweyn used it to get to Bath in 1013. However, it is probable that it was falling into disrepair, identified in the 1001 Bradford charter as imare (boundary), not herepath (army road), stræt (Roman road) or weg (way). Perhaps it had already been superseded as a route by the pre-historic ridgeway road nearby. In the north, a track led to the Roman road there, the Fosse Way (called stræt in charters for Nettleton and Grittleton),[1] and this is still sometimes remembered in the name of the lane, Rode Hill.

It is hard to determine which Box roads existed in the early medieval period and which, if any, had Saxon origins. Many of these tracks appear to have arisen from customary usage rather than planned construction. Having said that, some routes do have the appearance of longevity because of their condition and purpose. The routes which run down from the highland areas on the southern boundary appear to be historic, possibly Saxon. They give access to the By Brook and the mills known to exist there at the end of the Saxon period. These mills would have required manning and we might imagine that encouraged a small settlement comprising the miller and his family, carpenters and blacksmiths needed to repair the mill and carts, hauliers for transport, and horse minders. These roads afforded access to the areas of settlement for travellers and merchants, for the seasonal needs of the harvest and for building requirements transporting timber and occasionally stone.

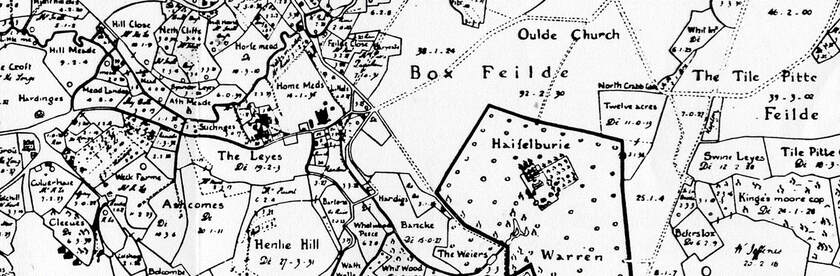

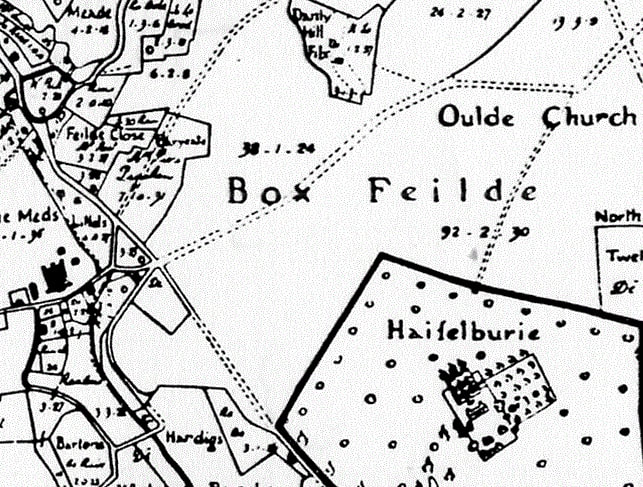

Based on appearances rather than definite evidence, we can speculate that some tracks in Box existed in Saxon times. Wyres Lane is one such, a track from the ancient ridgeway track next to the Roman road which goes past modern Hazelbury House, down Hazelbury Hill, through Bulls Lane to Box Mill and up Mill Lane to Slades Farm. In places the path has been used so much that it has cut a deep holloway and the banks of vegetation have risen up on either side.

The Roman road on the southern boundary has been used over long periods and it is possible that the Viking Sweyn used it to get to Bath in 1013. However, it is probable that it was falling into disrepair, identified in the 1001 Bradford charter as imare (boundary), not herepath (army road), stræt (Roman road) or weg (way). Perhaps it had already been superseded as a route by the pre-historic ridgeway road nearby. In the north, a track led to the Roman road there, the Fosse Way (called stræt in charters for Nettleton and Grittleton),[1] and this is still sometimes remembered in the name of the lane, Rode Hill.

It is hard to determine which Box roads existed in the early medieval period and which, if any, had Saxon origins. Many of these tracks appear to have arisen from customary usage rather than planned construction. Having said that, some routes do have the appearance of longevity because of their condition and purpose. The routes which run down from the highland areas on the southern boundary appear to be historic, possibly Saxon. They give access to the By Brook and the mills known to exist there at the end of the Saxon period. These mills would have required manning and we might imagine that encouraged a small settlement comprising the miller and his family, carpenters and blacksmiths needed to repair the mill and carts, hauliers for transport, and horse minders. These roads afforded access to the areas of settlement for travellers and merchants, for the seasonal needs of the harvest and for building requirements transporting timber and occasionally stone.

Based on appearances rather than definite evidence, we can speculate that some tracks in Box existed in Saxon times. Wyres Lane is one such, a track from the ancient ridgeway track next to the Roman road which goes past modern Hazelbury House, down Hazelbury Hill, through Bulls Lane to Box Mill and up Mill Lane to Slades Farm. In places the path has been used so much that it has cut a deep holloway and the banks of vegetation have risen up on either side.

Local Routes

The Saxons had a variety of names for their roads including pæth (path), anstiga (steep path) and fær (dangerous journey).

We can surmise that other Saxon routes existed in the area, such as a road to Bath (the closest market and town). We know that in a later period a route branched away from the village at Ashley Lane and wound its way to Bath crossing the River Avon where fording was best at Bathford and Bathampton. Clearly, access roads were needed to all activity sites and tracks would have been needed down to the mills on the By Brook, mentioned in the Domesday record. One of these was possibly Drewetts Mill, and a route still runs from Rudloe, past Millsplatt, and Drewetts, finally to Saltbox Farm. We know that salt carriers and drovers were active in the early medieval period and some people claim that the name Saltbox relates to this trade. However, another explanation (derived from colonial period of eastern USA) is that it refers to a building with two storeys in front and one behind, with a sloping catslide roof reminiscent of a wooden saltbox with its hinged sloping lid – which perfectly describes the present Saltbox building, constructed in 1784.

The Saxons had a variety of names for their roads including pæth (path), anstiga (steep path) and fær (dangerous journey).

We can surmise that other Saxon routes existed in the area, such as a road to Bath (the closest market and town). We know that in a later period a route branched away from the village at Ashley Lane and wound its way to Bath crossing the River Avon where fording was best at Bathford and Bathampton. Clearly, access roads were needed to all activity sites and tracks would have been needed down to the mills on the By Brook, mentioned in the Domesday record. One of these was possibly Drewetts Mill, and a route still runs from Rudloe, past Millsplatt, and Drewetts, finally to Saltbox Farm. We know that salt carriers and drovers were active in the early medieval period and some people claim that the name Saltbox relates to this trade. However, another explanation (derived from colonial period of eastern USA) is that it refers to a building with two storeys in front and one behind, with a sloping catslide roof reminiscent of a wooden saltbox with its hinged sloping lid – which perfectly describes the present Saltbox building, constructed in 1784.

Daily Paths

There were also more local paths for daily needs to allow workers to get to their strips in the common fields and to the lord’s lands especially at peak periods of ploughing, sowing, harvesting and the birth of infant animals. One instance in Box is Bar Yeate (a gate to a path that ran out into the open fields) as recorded in Allen’s 1626 map and recalled by the village name Bargates.[2] Similarly, Lypiatt in Neston, refers to a Leap-gate, probably stile, referring to a deer park.

Other paths were caused by habitual usage, running from domestic residences to woodland areas for firewood and wasteland where small animals were grazed. In the closes around the houses were the valuable items of the oxen, ploughs and breeding stock, which needed supervision and security. The need for daily access is one of the reasons why there are so many footpaths listed in Box. Regular access was also needed to any churches which existed at this time. In this connection, the lowest stones in the wall opposite the west end of St Thomas church are not inconsistent in terms of size and shape with Roman masonry, in which case they would likely be derived from part of the villa complex.

There were also more local paths for daily needs to allow workers to get to their strips in the common fields and to the lord’s lands especially at peak periods of ploughing, sowing, harvesting and the birth of infant animals. One instance in Box is Bar Yeate (a gate to a path that ran out into the open fields) as recorded in Allen’s 1626 map and recalled by the village name Bargates.[2] Similarly, Lypiatt in Neston, refers to a Leap-gate, probably stile, referring to a deer park.

Other paths were caused by habitual usage, running from domestic residences to woodland areas for firewood and wasteland where small animals were grazed. In the closes around the houses were the valuable items of the oxen, ploughs and breeding stock, which needed supervision and security. The need for daily access is one of the reasons why there are so many footpaths listed in Box. Regular access was also needed to any churches which existed at this time. In this connection, the lowest stones in the wall opposite the west end of St Thomas church are not inconsistent in terms of size and shape with Roman masonry, in which case they would likely be derived from part of the villa complex.

River Navigation

It remains uncertain if the By Brook was suitable for river transport during the early medieval period. Quite apart from the impedance imposed by watermills, an analysis of place-name elements associated with navigable rivers and watercourses suggests that few navigable rivers existed in Wessex.[3] Even so, there are three instances of stæð (wharf or landing place) recorded along Wiltshire rivers, although it is not clear whether these are deliberately constructed landing places or natural river banks. Even where some degree of navigation was possible, it may be that bulk goods could only be moved downstream.

The rivers were also an obstacle as much as a mode of transport. All around Box are places defined as fords (crossing points), such as Bradford-on-Avon, Bathford and Great Somerford (only navigable in summertime).[4] The rivers limited those residents who had no river transport to stay in their local areas and there are no identified fords in the parish of Box, indicating that people were probably able to cross the By Brook.

It remains uncertain if the By Brook was suitable for river transport during the early medieval period. Quite apart from the impedance imposed by watermills, an analysis of place-name elements associated with navigable rivers and watercourses suggests that few navigable rivers existed in Wessex.[3] Even so, there are three instances of stæð (wharf or landing place) recorded along Wiltshire rivers, although it is not clear whether these are deliberately constructed landing places or natural river banks. Even where some degree of navigation was possible, it may be that bulk goods could only be moved downstream.

The rivers were also an obstacle as much as a mode of transport. All around Box are places defined as fords (crossing points), such as Bradford-on-Avon, Bathford and Great Somerford (only navigable in summertime).[4] The rivers limited those residents who had no river transport to stay in their local areas and there are no identified fords in the parish of Box, indicating that people were probably able to cross the By Brook.

Conclusion

Some modern routes through the parish are clearly of great antiquity, but we have no means of telling which ones might be Saxon. Speculation about Anglo-Saxon Box is very difficult, not least because 'Box' as an entity may not even have existed until after the period described. Nonetheless, many contemporary routes provide access to woodland, meadows and the water mills and we might deduce that earlier people would have needed similar access. But clearly it isn't sufficient to simply remove the obviously modern roads such as the A4, or to suppose that the routes shown on the Allen maps must have been there at least as long as the field systems.

Some modern routes through the parish are clearly of great antiquity, but we have no means of telling which ones might be Saxon. Speculation about Anglo-Saxon Box is very difficult, not least because 'Box' as an entity may not even have existed until after the period described. Nonetheless, many contemporary routes provide access to woodland, meadows and the water mills and we might deduce that earlier people would have needed similar access. But clearly it isn't sufficient to simply remove the obviously modern roads such as the A4, or to suppose that the routes shown on the Allen maps must have been there at least as long as the field systems.

References

[1] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.115

[2] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.127

[3] John Blair (editor) Waterways and canal building in Medieval England, 2007, discussed in Alex Langland's PhD thesis Travel and Communication in the landscape of early medieval Wessex, 2013, University of Winchester), which suggests on the basis of the distribution of place-name elements such as hȳð (landing place), lād (waterway, load) and stæð (river bank).

[4] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.102

[1] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.115

[2] John Field, A History of English Field-names, 1993, Longman, p.127

[3] John Blair (editor) Waterways and canal building in Medieval England, 2007, discussed in Alex Langland's PhD thesis Travel and Communication in the landscape of early medieval Wessex, 2013, University of Winchester), which suggests on the basis of the distribution of place-name elements such as hȳð (landing place), lād (waterway, load) and stæð (river bank).

[4] Jennifer Ellen MacDonald, Travel and the Communications Network in Late Saxon Wessex, 2001, p.102