Dennis Richman’s Memories, 1910-15 In Tribute to David Ibberson January 2024

David Ibberson died in June 2022. He published a number of books about the history of Box and unearthed this article about life of Dennis Richman in the village before the First World War. David serialised it in the parish magazine in 1986 but it never got a wider audience. This article is a small tribute to David.

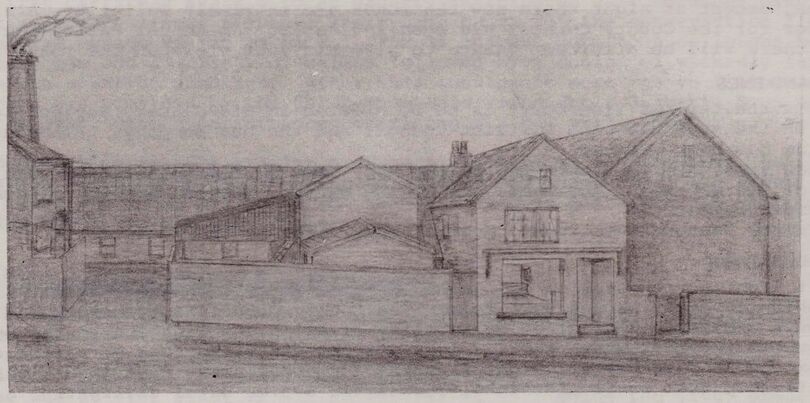

Dennis Richman moved to Millers, Box High Street, when he was 7 years old in 1910 and left for Market Lavington in 1915. Those brief five years made a deep impression on him and in 1986 David Ibberson recorded Dennis' s memories of village life before the First World War. Dennis’ father John William Richman (from Bradford-on-Avon) and his wife Martha came to Box in 1910 to manage the grocer’s business at Millers, then called Caple Stores, next door to the residential building which was known as Belle Vue. John was in charge of the provisions store but not the bakery next door. Dennis had several older siblings: two brothers who had already left home, William John, who had moved to London, and Arthur, who worked in the offices of Spear’s Bacon Factory, Bath, and two sisters at home, Olive Maud (1891-), who was an apprentice milliner with James Colmer, Bath, and Ruby Violet, aged 12 in 1910 and still at school. Here are Dennis’ s memories of the village and its people.

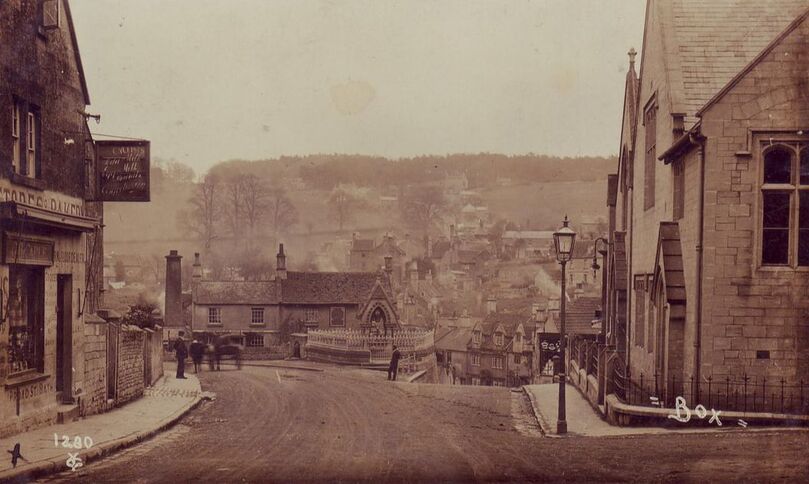

Arriving in Box, March 1910

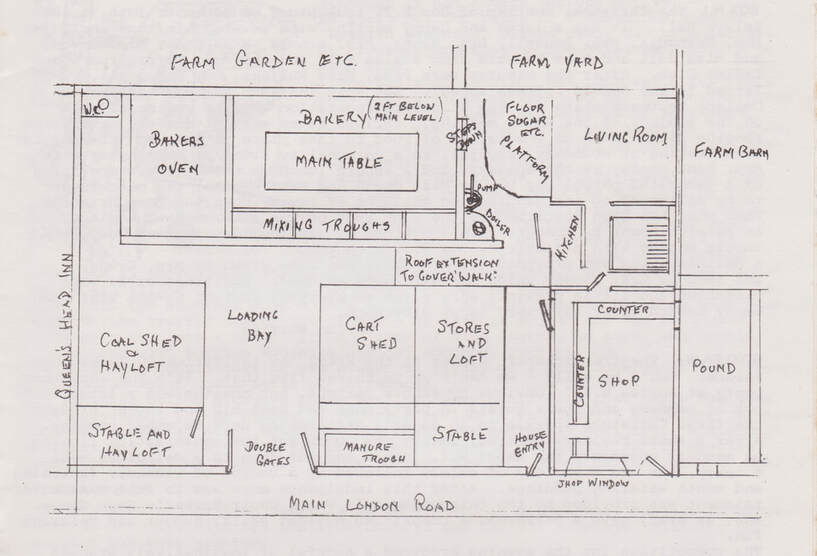

Ruby and I travelled to Box in the rear of the furniture van (horse-drawn, of course) with the goods and chattels and arrived about dinner time. Dad made us both a beautiful sandwich of freshly baked bread with farm butter and really cool ham, which we ate sitting on the rungs of the loft ladder under the cart shed roof. It was a beautiful spring day and we found great pleasure in exploring and poking into the mysteries of our abode-to-be. There were two stables, each with a horse within. We thought they were lovely animals, nice chestnutty colour and the inevitable dung heap, which was well contained in a walled surround. It didn’t spoil our sandwiches or our ginger beer from curiously-shaped glass bottles obtained by pushing in a glass marble which sealed the hole in the neck of the bottle.

There was a good-sized bakery, too, coal fired of course and, when the baking was finished and everything cleared up, we were allowed to go in to see the loaves and cakes and also the dough-mixing troughs, the large ovens and the long spatulas, with which the baker Mr Prebble and his assistant used to put the dough-filled oblong baking tins and cottage loaves in the oven. [Frederick William Prebble lived at Pye Corner in 1901 and then moved to 19 Fairmead View].

At the house end of the bakery was a large, wooden, platform area on which stood many sacks of different kinds of flour and sugar. On the adjoining house wall were large racks on which many kinds of biscuits were stacked in square tins. In the cart shed and loft were stored all manner of things, chests of tea, cheese, boxes of lard and numerous things of which we had never heard. Below was another store of currants, raisins, lemon peel and niceties for cake-making.

Dennis Richman moved to Millers, Box High Street, when he was 7 years old in 1910 and left for Market Lavington in 1915. Those brief five years made a deep impression on him and in 1986 David Ibberson recorded Dennis' s memories of village life before the First World War. Dennis’ father John William Richman (from Bradford-on-Avon) and his wife Martha came to Box in 1910 to manage the grocer’s business at Millers, then called Caple Stores, next door to the residential building which was known as Belle Vue. John was in charge of the provisions store but not the bakery next door. Dennis had several older siblings: two brothers who had already left home, William John, who had moved to London, and Arthur, who worked in the offices of Spear’s Bacon Factory, Bath, and two sisters at home, Olive Maud (1891-), who was an apprentice milliner with James Colmer, Bath, and Ruby Violet, aged 12 in 1910 and still at school. Here are Dennis’ s memories of the village and its people.

Arriving in Box, March 1910

Ruby and I travelled to Box in the rear of the furniture van (horse-drawn, of course) with the goods and chattels and arrived about dinner time. Dad made us both a beautiful sandwich of freshly baked bread with farm butter and really cool ham, which we ate sitting on the rungs of the loft ladder under the cart shed roof. It was a beautiful spring day and we found great pleasure in exploring and poking into the mysteries of our abode-to-be. There were two stables, each with a horse within. We thought they were lovely animals, nice chestnutty colour and the inevitable dung heap, which was well contained in a walled surround. It didn’t spoil our sandwiches or our ginger beer from curiously-shaped glass bottles obtained by pushing in a glass marble which sealed the hole in the neck of the bottle.

There was a good-sized bakery, too, coal fired of course and, when the baking was finished and everything cleared up, we were allowed to go in to see the loaves and cakes and also the dough-mixing troughs, the large ovens and the long spatulas, with which the baker Mr Prebble and his assistant used to put the dough-filled oblong baking tins and cottage loaves in the oven. [Frederick William Prebble lived at Pye Corner in 1901 and then moved to 19 Fairmead View].

At the house end of the bakery was a large, wooden, platform area on which stood many sacks of different kinds of flour and sugar. On the adjoining house wall were large racks on which many kinds of biscuits were stacked in square tins. In the cart shed and loft were stored all manner of things, chests of tea, cheese, boxes of lard and numerous things of which we had never heard. Below was another store of currants, raisins, lemon peel and niceties for cake-making.

Running the Shop

Every day or two, the GWR horse and dray would arrive (making local deliveries from Box Station depot). They brought all manner of goods for the establishment. The driver had a shiny black peak to his railway hat and a ginger moustache. He was a really jolly fellow and used to ask me, “Whose fathers your mother?” I was always trying to fathom it out.

Sometimes when wasps were buzzing around, my father and friends would go out at night and dig any known nests. Wasps were a menace especially on the business premises, what with sacks of sugar and jams and many other sweetmeats, the place was a continuous hiss with them. It seemed funny to see six or so jam pots to trap the wasps hung outside on each side of the shop front windows. At the bakery sugar platform, flying wasps were almost as dense as gratfly (sic) and we used a piece of flat board to fan our way through them. We all received many stings but they didn’t frighten us much. Mother used the blue-bag on us to ease the pain a bit.

Every day or two, the GWR horse and dray would arrive (making local deliveries from Box Station depot). They brought all manner of goods for the establishment. The driver had a shiny black peak to his railway hat and a ginger moustache. He was a really jolly fellow and used to ask me, “Whose fathers your mother?” I was always trying to fathom it out.

Sometimes when wasps were buzzing around, my father and friends would go out at night and dig any known nests. Wasps were a menace especially on the business premises, what with sacks of sugar and jams and many other sweetmeats, the place was a continuous hiss with them. It seemed funny to see six or so jam pots to trap the wasps hung outside on each side of the shop front windows. At the bakery sugar platform, flying wasps were almost as dense as gratfly (sic) and we used a piece of flat board to fan our way through them. We all received many stings but they didn’t frighten us much. Mother used the blue-bag on us to ease the pain a bit.

We didn’t have much scree (time off school) as we were taken to school the day after our arrival and enrolled. I was only seven years of age, so it was to Miss Kate Sweeney’s class that I was taken. Mr Burrows was headmaster but he was replaced by Oliver Drew, who was very fond of teaching us the Welsh National Anthem. He did try to teach us in Welsh but without success. He was a good sportsman and enjoyed cricket, which proved to be rather dangerous using a hard ball on the stone playground. Being a Church of England school, we sang a hymn every morning and evening and at midday we sang grace. We had scripture lessons each morning. The girls’ school adjoined ours but was separated by large folding doors, which were opened for morning prayers and special occasions singing together.

A rough stone playground was separated from the road by a strong stone wall. Traffic was practically non-existent, maybe the occasional farm cart or animals being taken from one grazing to another or market, all moving at a leisurely pace, spreading lots of dung over the road. Right opposite the school was the brewery. We used to get the full smell of the malt.

Church Choir

In time I was enrolled in the church choir, which in those days was always well-attended. Mr Perrin from Ashley was our choirmaster. He was tall, thin, grey-haired and a bit bent over, which we thought was old age. The church lighting then consisted of bare, gas, fish-tailed lights, no gas mantles of any kind but it was better than candles and enough to see by. It was candles in most homes and our eyes had become accustomed to it. We had choir practice nights of course and boys only. Mr Perrin had to make an awkward detour to get to the organ. As soon as he dismissed us we would all rush back behind the vestry and turn off the gas at the meter. With its decaying stone tombs, the churchyard also gave great scope for playing around, ghosts and that sort of thing. Sunday School outings were a great event and we were very excited as we climbed into a large farm cart which carried us to Neston Park.

The vicar then was the Rev White. He was a great favourite with us children. The grown-ups said that he always presented a good, sensible sermon, but to us choirboys it was a bit long. Rev White was short, rotund and had rather less hair than is desirable. Having short legs, he walked rather quickly with a shuffling gait, such speed being essential if he were to cover the same ground as someone of taller stature. His clerical duties involved regular visits to the school. As if to assess the size of a child’s brain, he would tap them on the head and say, I know what you’re thinking. This was a clever ploy because common sense would make you reconsider any planned misdemeanours. Of course, the truth was that years of experience effectively did enable him to read minds.

Life in Pre-War Box

From the rear window of our house, we could see the cricket field and behind that the Middlehill Tunnel with the north bank of the cutting rising very steeply toward Goulstone’s Farm fields at the top. Rabbits galore lived on the bank and many blackberry bushes were there. In spring, the banks were spread with lovely long-stemmed primroses. The Ley was in a lovely little valley (Box Bottom) and at the bottom ran a stream, the overflow from Pinch Pond. The valley was noted for the abundance of Kingcups and Cuckoo Flowers that mingled with the rushes that grew there. Mr Aust’s house was the only one overlooking the valley at that time and the woods backing the hill from the Ley Road to Hazelbury Manor were always a grand site.

The mowing grass fields were a pretty sight with many different kinds of flowers and, in dry weather, we spent much time playing in them when the farmer wasn’t about. As the horse-drawn mowing machine went round and round the fields, we enjoyed the smell given off by cut grass. Usually, a dog or two ran around in the vicinity of the mowers, endeavouring to catch any rabbits, rats or fieldmice that were disturbed. According to the weather, there were then periods of turning the cut grass to dry before it was gathered. This was done with wooden rakes, often causing blisters on hands, but quite a number of women, farmers’ wives and daughters, helped the farmhands. The elders had their jugs of beer and we the usual cold tea.

Winter time, when cold winds and frosts made our ears tingle painfully. For warming fingers, we used to make hand-warmers to carry with us. These comprised a smallish tin with holes punched in the lid and bottom. We put a small piece of smouldering rag in this, which burnt gradually depending on how fast we swung it.

Dennis regularly walked around the village lanes and footpaths and recalled walking from the High Street, past the home of Miss Brame at Sunnyside (now By Brook House), towards Alcombe and Middlehill:

There was a haunted house too, half way up the lane, all overgrown with ivy and creepers, windows broken and stonework decaying. A place to be avoided and scurried past at night. We turned off right opposite the big gates of Miss Minnow’s large house. She was a mystery to us. We heard she kept cats as spinsters are wont to do. Nobody ever seed (sic) her though. Then we passed a row of lovely tall beech trees and past Squire Northey’s house (Cheney Court) to where we youngsters went at Christmas time to get our penny and an orange. The memory of a very large log-burning fireplace still remains in my mind This is Ditteridge, a very small hamlet with a very small church. Mark Mays, who helped in the shop and ran errands, lived there and my friend’s Frank Hancock’s family.

The Box Brook, how pleasant it was! What happy times we had paddling in the shallows on the smooth pebbles and, in some places, sand. The lovely shade of willow trees and others much larger. We used to sit and eat our picnic food and drink bottles of cold tea.

Outbreak of War

The London Road outside the Bear Inn reminds me of pre-war days when civil engineers dug the road foundations very deep and set down a really good solid base on the “London to Avonmouth” road as they called it. It certainly looked as though they were doing a good job and it proved very worthwhile when the 1914-18 war began. The road was able to withstand the rigours and vibrations of the old solid-tyred London buses as they rumbled on to Avonmouth to be loaded onto ships to take them to the troops in France.

Right at the start of the war, I remember seeing a poor old tramp with his tins (cooking containers) being arrested as a suspect German spy. That took place on The Wharf Bridge before sentries were posted to guard Box Tunnel and the rail track. I was at the Scouts’ summer camp on Kingsdown when news of the war with Germany was broken to us because they had overrun neutral Belgium. The news caused much excitement everywhere and brought forth full patriotism among people. It will be over in four weeks, they said, but it lasted four years. One night it had been raining and our assistant Scoutmaster had ridden his new-fangled motor-bike machine down a tortuous, boulder-strewn, very steep, narrow lane that even horses found difficult to walk. When he reached the tent, he was soaking wet and all his clothing was a sight because the continuing spills had squashed all the eggs and tomatoes, he was bringing us to eat. It was very late and pitch black too, but it was a brave effort on his part. His name was Jim Browning from Box Mill.

One time, we were at home and heard a noise we thought was a farm tractor (they always made a terrific clatter). Everyone rushed out and saw the first air contraption (aircraft) passing overhead. It was just a skeleton framework with wings and a man sitting driving it. It wasn’t very high, just above the tree tops at Quarry Hill and following the contours of the land. The name Claude Grahame-White, aviator, soon became known in the area and, after a while, the Daily Mail plane was seen.

Church Choir

In time I was enrolled in the church choir, which in those days was always well-attended. Mr Perrin from Ashley was our choirmaster. He was tall, thin, grey-haired and a bit bent over, which we thought was old age. The church lighting then consisted of bare, gas, fish-tailed lights, no gas mantles of any kind but it was better than candles and enough to see by. It was candles in most homes and our eyes had become accustomed to it. We had choir practice nights of course and boys only. Mr Perrin had to make an awkward detour to get to the organ. As soon as he dismissed us we would all rush back behind the vestry and turn off the gas at the meter. With its decaying stone tombs, the churchyard also gave great scope for playing around, ghosts and that sort of thing. Sunday School outings were a great event and we were very excited as we climbed into a large farm cart which carried us to Neston Park.

The vicar then was the Rev White. He was a great favourite with us children. The grown-ups said that he always presented a good, sensible sermon, but to us choirboys it was a bit long. Rev White was short, rotund and had rather less hair than is desirable. Having short legs, he walked rather quickly with a shuffling gait, such speed being essential if he were to cover the same ground as someone of taller stature. His clerical duties involved regular visits to the school. As if to assess the size of a child’s brain, he would tap them on the head and say, I know what you’re thinking. This was a clever ploy because common sense would make you reconsider any planned misdemeanours. Of course, the truth was that years of experience effectively did enable him to read minds.

Life in Pre-War Box

From the rear window of our house, we could see the cricket field and behind that the Middlehill Tunnel with the north bank of the cutting rising very steeply toward Goulstone’s Farm fields at the top. Rabbits galore lived on the bank and many blackberry bushes were there. In spring, the banks were spread with lovely long-stemmed primroses. The Ley was in a lovely little valley (Box Bottom) and at the bottom ran a stream, the overflow from Pinch Pond. The valley was noted for the abundance of Kingcups and Cuckoo Flowers that mingled with the rushes that grew there. Mr Aust’s house was the only one overlooking the valley at that time and the woods backing the hill from the Ley Road to Hazelbury Manor were always a grand site.

The mowing grass fields were a pretty sight with many different kinds of flowers and, in dry weather, we spent much time playing in them when the farmer wasn’t about. As the horse-drawn mowing machine went round and round the fields, we enjoyed the smell given off by cut grass. Usually, a dog or two ran around in the vicinity of the mowers, endeavouring to catch any rabbits, rats or fieldmice that were disturbed. According to the weather, there were then periods of turning the cut grass to dry before it was gathered. This was done with wooden rakes, often causing blisters on hands, but quite a number of women, farmers’ wives and daughters, helped the farmhands. The elders had their jugs of beer and we the usual cold tea.

Winter time, when cold winds and frosts made our ears tingle painfully. For warming fingers, we used to make hand-warmers to carry with us. These comprised a smallish tin with holes punched in the lid and bottom. We put a small piece of smouldering rag in this, which burnt gradually depending on how fast we swung it.

Dennis regularly walked around the village lanes and footpaths and recalled walking from the High Street, past the home of Miss Brame at Sunnyside (now By Brook House), towards Alcombe and Middlehill:

There was a haunted house too, half way up the lane, all overgrown with ivy and creepers, windows broken and stonework decaying. A place to be avoided and scurried past at night. We turned off right opposite the big gates of Miss Minnow’s large house. She was a mystery to us. We heard she kept cats as spinsters are wont to do. Nobody ever seed (sic) her though. Then we passed a row of lovely tall beech trees and past Squire Northey’s house (Cheney Court) to where we youngsters went at Christmas time to get our penny and an orange. The memory of a very large log-burning fireplace still remains in my mind This is Ditteridge, a very small hamlet with a very small church. Mark Mays, who helped in the shop and ran errands, lived there and my friend’s Frank Hancock’s family.

The Box Brook, how pleasant it was! What happy times we had paddling in the shallows on the smooth pebbles and, in some places, sand. The lovely shade of willow trees and others much larger. We used to sit and eat our picnic food and drink bottles of cold tea.

Outbreak of War

The London Road outside the Bear Inn reminds me of pre-war days when civil engineers dug the road foundations very deep and set down a really good solid base on the “London to Avonmouth” road as they called it. It certainly looked as though they were doing a good job and it proved very worthwhile when the 1914-18 war began. The road was able to withstand the rigours and vibrations of the old solid-tyred London buses as they rumbled on to Avonmouth to be loaded onto ships to take them to the troops in France.

Right at the start of the war, I remember seeing a poor old tramp with his tins (cooking containers) being arrested as a suspect German spy. That took place on The Wharf Bridge before sentries were posted to guard Box Tunnel and the rail track. I was at the Scouts’ summer camp on Kingsdown when news of the war with Germany was broken to us because they had overrun neutral Belgium. The news caused much excitement everywhere and brought forth full patriotism among people. It will be over in four weeks, they said, but it lasted four years. One night it had been raining and our assistant Scoutmaster had ridden his new-fangled motor-bike machine down a tortuous, boulder-strewn, very steep, narrow lane that even horses found difficult to walk. When he reached the tent, he was soaking wet and all his clothing was a sight because the continuing spills had squashed all the eggs and tomatoes, he was bringing us to eat. It was very late and pitch black too, but it was a brave effort on his part. His name was Jim Browning from Box Mill.

One time, we were at home and heard a noise we thought was a farm tractor (they always made a terrific clatter). Everyone rushed out and saw the first air contraption (aircraft) passing overhead. It was just a skeleton framework with wings and a man sitting driving it. It wasn’t very high, just above the tree tops at Quarry Hill and following the contours of the land. The name Claude Grahame-White, aviator, soon became known in the area and, after a while, the Daily Mail plane was seen.

Villagers

As the weather became warmer, we made friends with the Daniell Family who had Manor Farm next to us. They had several daughters, two around our age and going to school, several sons a number of years older and the older three were grown up. The children Dennis knew were Dorothy (later well-known in the village by her married name Dot Taylor) and Olive (who never married).

Of course, the Daniells had a separator for the cream and skimmed milk in the dairy, a place which was always kept scrupulously clean but always had that certain dairy smell about the place. It was in the rear of the house, which had very large, sparsely-furnished rooms. The ground floors were flag stones, no carpets in those days, so the studded boots created a hollow clatter on them. It took a while before my sister Ruby and I could pluck up courage and saunter among the cows.

Good Friday, time for hot cross buns and Frederick William Prebble, our baker, would prepare the stuff, arriving early to make and bake the buns. They were delivered to the customers hot and I would get up early and help take them round. It always seemed a bright, sunny morning – but I wonder? Usually, the afternoons were spent primrosing and walking through the woods over carpets of bluebells.

Dr Martin! A well-known figure who always rode a magnificent chestnut-coloured stallion. The doctor used to swear a bit but everyone seemed to like and respect him and he did cut a dashing figure on his horse. In passing, Dr Symes (a contemporary of Dr Martin) was a very nice man and a different type, perhaps a little more refined.

Constable Carpenter. Me, being a member of the “Band of Hope” (Christian Temperance movement), I never entered that place (The Queen’s Head). On the other hand, I cannot remember any drunks or disturbances. In any case, burly Constable Carpenter was able to deal with the likes of them. He would clip offenders round the ear. I think things changed a lot when slender Constable Leaky took over. Constable Carpenter’s son “Curly” Carpenter was an apprentice in the bakery.

At some cottages above the road junction (in Wharf Cottages) lived the Bullock family, who had two sons Allen and Howard. They owned a motor-cycle and sidecar and invented what they called “Bullock’s Double Grip” which was an improved way of joining the driving belt to the rear wheel. They put a large board advertising their patent overlooking the road.

Behind the fountain were gardens of a row of cottages (the Clock House, near McColl's, the store formerly owned by the Co-op) and behind them a small single-roomed cottage, in which lived a man who wore black clothes with an old Methodist-style black hat with a broad, flat brim. He also had a black beard and hair. On a board outside the cottage, he claimed to be “Professor Wick”, a phrenologist. We children gave him a wide berth.

As the weather became warmer, we made friends with the Daniell Family who had Manor Farm next to us. They had several daughters, two around our age and going to school, several sons a number of years older and the older three were grown up. The children Dennis knew were Dorothy (later well-known in the village by her married name Dot Taylor) and Olive (who never married).

Of course, the Daniells had a separator for the cream and skimmed milk in the dairy, a place which was always kept scrupulously clean but always had that certain dairy smell about the place. It was in the rear of the house, which had very large, sparsely-furnished rooms. The ground floors were flag stones, no carpets in those days, so the studded boots created a hollow clatter on them. It took a while before my sister Ruby and I could pluck up courage and saunter among the cows.

Good Friday, time for hot cross buns and Frederick William Prebble, our baker, would prepare the stuff, arriving early to make and bake the buns. They were delivered to the customers hot and I would get up early and help take them round. It always seemed a bright, sunny morning – but I wonder? Usually, the afternoons were spent primrosing and walking through the woods over carpets of bluebells.

Dr Martin! A well-known figure who always rode a magnificent chestnut-coloured stallion. The doctor used to swear a bit but everyone seemed to like and respect him and he did cut a dashing figure on his horse. In passing, Dr Symes (a contemporary of Dr Martin) was a very nice man and a different type, perhaps a little more refined.

Constable Carpenter. Me, being a member of the “Band of Hope” (Christian Temperance movement), I never entered that place (The Queen’s Head). On the other hand, I cannot remember any drunks or disturbances. In any case, burly Constable Carpenter was able to deal with the likes of them. He would clip offenders round the ear. I think things changed a lot when slender Constable Leaky took over. Constable Carpenter’s son “Curly” Carpenter was an apprentice in the bakery.

At some cottages above the road junction (in Wharf Cottages) lived the Bullock family, who had two sons Allen and Howard. They owned a motor-cycle and sidecar and invented what they called “Bullock’s Double Grip” which was an improved way of joining the driving belt to the rear wheel. They put a large board advertising their patent overlooking the road.

Behind the fountain were gardens of a row of cottages (the Clock House, near McColl's, the store formerly owned by the Co-op) and behind them a small single-roomed cottage, in which lived a man who wore black clothes with an old Methodist-style black hat with a broad, flat brim. He also had a black beard and hair. On a board outside the cottage, he claimed to be “Professor Wick”, a phrenologist. We children gave him a wide berth.

Dennis Richman was only a boy when he lived in Box. The family moved to Market Lavington, then to Bath. Dennis left home and married Hannah Jane Roberts from Bathford in 1925, when he was working as an engine fitter. The marriage didn’t last and they divorced in 1946.[1] Dennis married again to Leila Wyatt in Bath later that year. Dennis died in 1992 but the memories of Box village stayed with him throughout his life.

Reference

[1] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 March 1946

[1] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 March 1946