Railway Buildings and More Alan Payne and John Froud April 2017

Tunnels

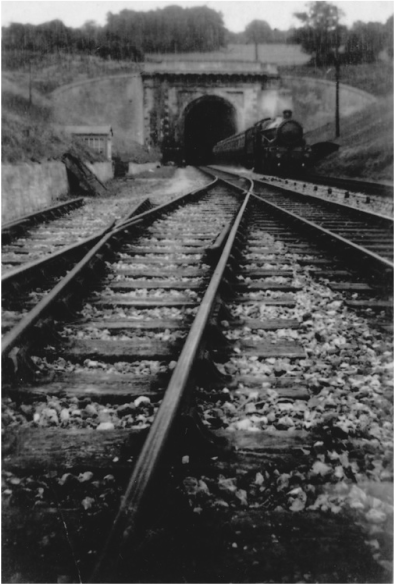

Box Tunnel has become the symbol of the village. When it was built in 1841 it was perceived as a grand statement merging the old and new, completely contrary to architectural styles of the time. For example, in 1834 when the old Westminster Hall, London, burnt down, the new Houses of Parliament that replaced them were in the fashionable Gothic style that dominated early Victorian imagination. Box Tunnel harkened back to classical Roman features as a statement of eternal grandeur.

Much has been written about the architecture of the tunnel portals (entrance facades). The west portal, immortalised in the Thomas the Tank Engine illustrations, is still prominent on the London to Bath Turnpike Road (A4), with an imposing face with a Palladian (Classical) arch, taller than absolutely needed. It is different to Brunel's usual Gothic (highly decorated) style, possibly inspired by Brunel's visit to Italy in 1840 and was listed as a historic monument Grade II in 1985.[1] By contrast, the east portal is at the end of a long, deep cutting and is more austere.

Box Tunnel has become the symbol of the village. When it was built in 1841 it was perceived as a grand statement merging the old and new, completely contrary to architectural styles of the time. For example, in 1834 when the old Westminster Hall, London, burnt down, the new Houses of Parliament that replaced them were in the fashionable Gothic style that dominated early Victorian imagination. Box Tunnel harkened back to classical Roman features as a statement of eternal grandeur.

Much has been written about the architecture of the tunnel portals (entrance facades). The west portal, immortalised in the Thomas the Tank Engine illustrations, is still prominent on the London to Bath Turnpike Road (A4), with an imposing face with a Palladian (Classical) arch, taller than absolutely needed. It is different to Brunel's usual Gothic (highly decorated) style, possibly inspired by Brunel's visit to Italy in 1840 and was listed as a historic monument Grade II in 1985.[1] By contrast, the east portal is at the end of a long, deep cutting and is more austere.

|

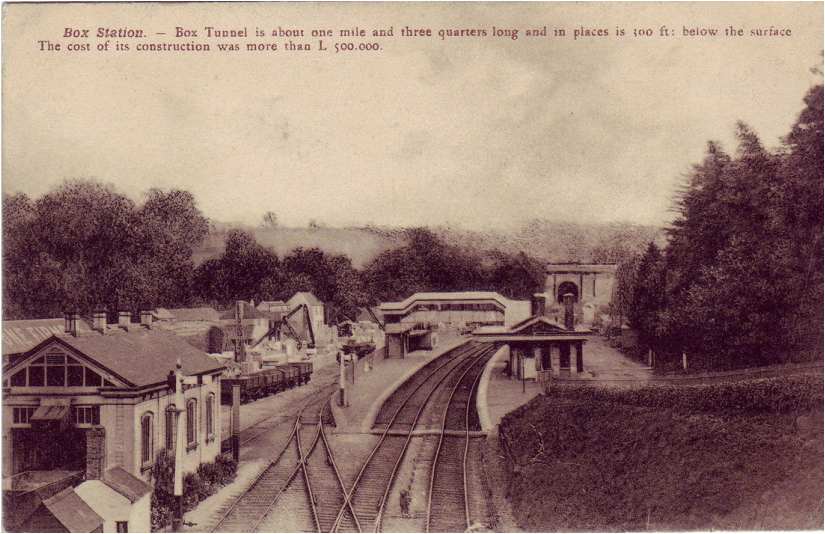

Box Station Platforms

Box Station wasn't ready when the line was opened. A report in October 1841 refers to its poor condition in such a dreadful state, owing to the late rains, that the inhabitants of Box and Ashley, particularly females, cannot wade through the mud and clay to go by the trains, so that they prefer the conveyance of the coaches.[2] The report suggested that the remedy would be a wagon-load or two of rubble, or planks laid down for about one hundred yards. The station was originally a wooden building constructed by Edward Streetor in 1841, clearly made at the last minute before the line opened.[3] |

John Froud Wrote

The single-sided platform arrangements were only implemented at major stations for example Slough, Taunton, Reading, Oxford and Exeter.[4] At Box, a single line was only available at time of opening through Box Tunnel, but within 48hours the down line was completed.[5] I don’t think there is any doubt that two platforms were provided at Box station from the start. An 1845 indenture shows structures on both platforms, that is on both up and down lines.[6]

Works were sanctioned in July 1852 by the GWR Board of Directors to enlarge Box Station. In summary this involved replacing the original wooden building with a new stone building, and extending the down platform to accommodate these changes. These works are assessed to have taken place circa 1855.[7] The up platform may have been extended at this time, but I conclude that the original shelter provided on the up platform from opening in 1841 lasted to 1965. From opening passengers would have used whichever platform suited the direction they wished to travel.

The single-sided platform arrangements were only implemented at major stations for example Slough, Taunton, Reading, Oxford and Exeter.[4] At Box, a single line was only available at time of opening through Box Tunnel, but within 48hours the down line was completed.[5] I don’t think there is any doubt that two platforms were provided at Box station from the start. An 1845 indenture shows structures on both platforms, that is on both up and down lines.[6]

Works were sanctioned in July 1852 by the GWR Board of Directors to enlarge Box Station. In summary this involved replacing the original wooden building with a new stone building, and extending the down platform to accommodate these changes. These works are assessed to have taken place circa 1855.[7] The up platform may have been extended at this time, but I conclude that the original shelter provided on the up platform from opening in 1841 lasted to 1965. From opening passengers would have used whichever platform suited the direction they wished to travel.

Demands For Station Improvement, 1863

The inadequacy of Box Station became more apparent as time went on. A public meeting was held in December 1863 to request the Company made improvements.[8] It was attended by most of the notables of the village, chaired by Lieutenant-Colonel Northey at the demand of Captain Woodgate of Ardgay, Middlehill, who had circulated pamphlets.

The inadequacy of Box Station became more apparent as time went on. A public meeting was held in December 1863 to request the Company made improvements.[8] It was attended by most of the notables of the village, chaired by Lieutenant-Colonel Northey at the demand of Captain Woodgate of Ardgay, Middlehill, who had circulated pamphlets.

Residents were dissatisfied with all arrangements at the station, including services and accommodation. One grievance was that travellers were unable to get to London and back to Box Station in daylight hours without paying express fares or going via Bath or Chippenham. Although there were seventeen trains per day many didn't stop at Box, which was sacrificed for the through traffic. And the punctuality of the trains was brought into serious dispute.

In a telling contribution by WJ Brown of Middlehill House, further issues emerged: that there was no siding for goods trains to be loaded and unloaded and accommodation for passengers was inadequate with goods being stored in the waiting room. Captain Straun Robertson of Spa House referred to cheeses and corn being stored around the sides of the room. The Rev HN Rynd said that the up-platform was too close to the rails, highly dangerous because it could only be accessed by crossing the rails, and was not sheltered from the weather at any season. There were two platforms by 1863, but no passenger footbridge over the lines.

The complaints went on and on. The bank engine for assisting trains through the tunnel was continually in movement and a danger to passengers. Mr Bruce who lived in Ashley House, a director of the Bristol and Exeter Railway, advocated a gentle approach to GWR but the meeting concluded with plans to draw up a petition.

In a telling contribution by WJ Brown of Middlehill House, further issues emerged: that there was no siding for goods trains to be loaded and unloaded and accommodation for passengers was inadequate with goods being stored in the waiting room. Captain Straun Robertson of Spa House referred to cheeses and corn being stored around the sides of the room. The Rev HN Rynd said that the up-platform was too close to the rails, highly dangerous because it could only be accessed by crossing the rails, and was not sheltered from the weather at any season. There were two platforms by 1863, but no passenger footbridge over the lines.

The complaints went on and on. The bank engine for assisting trains through the tunnel was continually in movement and a danger to passengers. Mr Bruce who lived in Ashley House, a director of the Bristol and Exeter Railway, advocated a gentle approach to GWR but the meeting concluded with plans to draw up a petition.

John Froud Added

In November 1875 the lines through Box were changed to mixed gauge by the addition of a rail to the broad gauge to accommodate narrow (standard) gauge trains. In a fatal accident in November 1875 the Company accepted that the up platform was too narrow and needed to have a shelter.[9] I have not seen the Inspector’s report on the change in gauge and the comment regarding the need for a shelter is interesting as one was already shown on GWR plans from about 1845 and 1855. Another fatal accident on 30 September 1876 found that neither platform complied with the Company's standard 500 feet, the platform on the up line being 423 feet and that on the down line only 363 feet.[10] The widening, lengthening and other works to the up platform did not take place until 1897 – the provision of the signal box on the up platform taking place at the same time.

In November 1875 the lines through Box were changed to mixed gauge by the addition of a rail to the broad gauge to accommodate narrow (standard) gauge trains. In a fatal accident in November 1875 the Company accepted that the up platform was too narrow and needed to have a shelter.[9] I have not seen the Inspector’s report on the change in gauge and the comment regarding the need for a shelter is interesting as one was already shown on GWR plans from about 1845 and 1855. Another fatal accident on 30 September 1876 found that neither platform complied with the Company's standard 500 feet, the platform on the up line being 423 feet and that on the down line only 363 feet.[10] The widening, lengthening and other works to the up platform did not take place until 1897 – the provision of the signal box on the up platform taking place at the same time.

Footbridge

The lack of restrictions on travellers walking across rails on their own initiative continued for many years. In 1882 John Stiles aged 62 was killed by a goods train when crossing the line.[11] The accident forced the directors' hands and the Box footbridge and several others were built in 1884 at a cost of £180.[12] When built, the footbridge was not covered and it is assessed that this didn't take place until 1897 when the platform works were carried out.

The lack of restrictions on travellers walking across rails on their own initiative continued for many years. In 1882 John Stiles aged 62 was killed by a goods train when crossing the line.[11] The accident forced the directors' hands and the Box footbridge and several others were built in 1884 at a cost of £180.[12] When built, the footbridge was not covered and it is assessed that this didn't take place until 1897 when the platform works were carried out.

There were still accidents however and in 1899 a fund was started by Mr RJ Marsh of the stone firm Marsh, Son and Gibbs to reward a Gallant Rescue Attempt in which ganger Charles Curtis was seriously injured.[13] A woman on the platform fell into the track and Mr Curtis dragged her over onto the other line seconds before an express train thundered past doing 60 miles per hour. Mr Curtis was awarded a medal by St John's Ambulance and survived a further 30 years.

Mill Lane Halt

For decades there had been requests for GWR to build a halt in central Box.[14] In July 1914 the Parish Council made a formal application which was declined on the grounds that the heavy expenses in the erection of a halt did not justify ... proceeding.

Led by G Bradfield and TH Lambert the council encouraged a petition which started with residents at Box Hill, but it all got shelved after the outbreak of war a short time later.

Mill Lane Halt was eventually opened on 31 March 1930.[15] Costing £800, it was built on an embanked timber platform, later replaced with a concrete base and corrugated iron shelter. The platform length could only accommodate the last four carriages of a train and travellers had to use those carriages to access the station. By the 1950s there were platforms on both sides of the track.

For decades there had been requests for GWR to build a halt in central Box.[14] In July 1914 the Parish Council made a formal application which was declined on the grounds that the heavy expenses in the erection of a halt did not justify ... proceeding.

Led by G Bradfield and TH Lambert the council encouraged a petition which started with residents at Box Hill, but it all got shelved after the outbreak of war a short time later.

Mill Lane Halt was eventually opened on 31 March 1930.[15] Costing £800, it was built on an embanked timber platform, later replaced with a concrete base and corrugated iron shelter. The platform length could only accommodate the last four carriages of a train and travellers had to use those carriages to access the station. By the 1950s there were platforms on both sides of the track.

|

There was a small corrugated iron sentry box at the bottom of steep steps at the halt where tickets could be issued and checked.[16] The senior porter was responsible for manning the office and accounting to the Station Master for money received from travellers.

The platforms on top of Mill Lane embankment were very exposed and very small shelters were built for the protection of passengers, rather like bus shelters. Steam trains sometimes had a problem re-starting after stopping due to wheel slip. Mill Lane Halt was closed on 4 January 1965 along with Box Station as part of the Beeching cuts to the rail service. Right: This remarkable photo is believed to be the only picture of the ticket office for Mill Lane Halt (the shed on the right). It was taken by Richard Pinker in 1960. |

Signal boxes

There were two signal cabins at Box.[17] The western signal cabin close to the engine shed is believed to have been authorised in 1873 and elevated on the bridge wing wall. It is shown on an 1887 drawing. The eastern locking box was associated with construction of goods shed and sidings in 1877.

There were two signal cabins at Box.[17] The western signal cabin close to the engine shed is believed to have been authorised in 1873 and elevated on the bridge wing wall. It is shown on an 1887 drawing. The eastern locking box was associated with construction of goods shed and sidings in 1877.

The station was connected with electric telegraph from at least December 1847 when the up line to London had the equipment installed.[18] Because of the danger in the Tunnel, a wire was installed along the up line to ring an alarm bell in the Corsham and Box signal boxes when broken.[19] It was for the use of train operators and workmen in the tunnel in addition to a time system in the Box Signal box monitoring passenger trains that took more than 8 minutes to arrive from Corsham, longer for goods trains.

Coal House

Because of the needs of the steam engines, coal was needed in bulk and authorisation for building a covered coal house, lamp room and railway store was given in 1861. The story of the Coal House is given elsewhere on the website and further research from John Froud has added important New Evidence that it was not a railway building.

Because of the needs of the steam engines, coal was needed in bulk and authorisation for building a covered coal house, lamp room and railway store was given in 1861. The story of the Coal House is given elsewhere on the website and further research from John Froud has added important New Evidence that it was not a railway building.

|

Rails

Rails were, of course, fundamental to the running of the rail-way, sometimes called the permanent way. But in 1841 there was no history to their use other than the local operation of rail tracks to carry materials like coal and slate short distances on private quarry works. With this in mind Brunel build his broad gauge track to give great speed and a less bumpy ride. Ironically, in Brunel’s initial design for the broad gauge track he anchored the track using piles and caused a very uncomfortabe ride.[20] But this was unsuitable for the Box Tunnel where runaway trains could have sped passenger trains to disaster. So inside the tunnel Brunel used a new permanent way where thin plates of iron were laid, their inner edges being supported upon a thick layer of felt. This caused the rails to bend under the weight of passing trains, slowing their progress.[21] Much of the rail line was the work of Thomas Edward Milles Marsh (1818-1907) who had been born at Biddestone and became Resident Engineer in charge of the permanent way during the building of the line through the Tunnel.[22] Brunel was obviously pleased with the result and Marsh later worked as Resident Engineer on the permanent-way work (track) for Brunel's plans for the Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth Railway, dying decades later at Grosvenor Place, Bath aged 89 years. |

The 7 foot broad-gauge line, used by Brunel in preference to the standard 4 foot 8½ inch track, never became the accepted track. In 1875 a mixed gauge was laid through Box Tunnel accommodating both systems and the track was only fully changed to standard gauge in May 1892 when the last broad gauge train left Paddington.[23] The wide-gauge rail tracks, which were obsolete after their replacement with narrow-gauge, were often used as standing gate posts.[24] The broad gauge rails are referred to as Bridge Rail due to their profile. Their use did continue after the broad gauge ceased in May 1892 but did then get used for fencing and other purposes.[25]

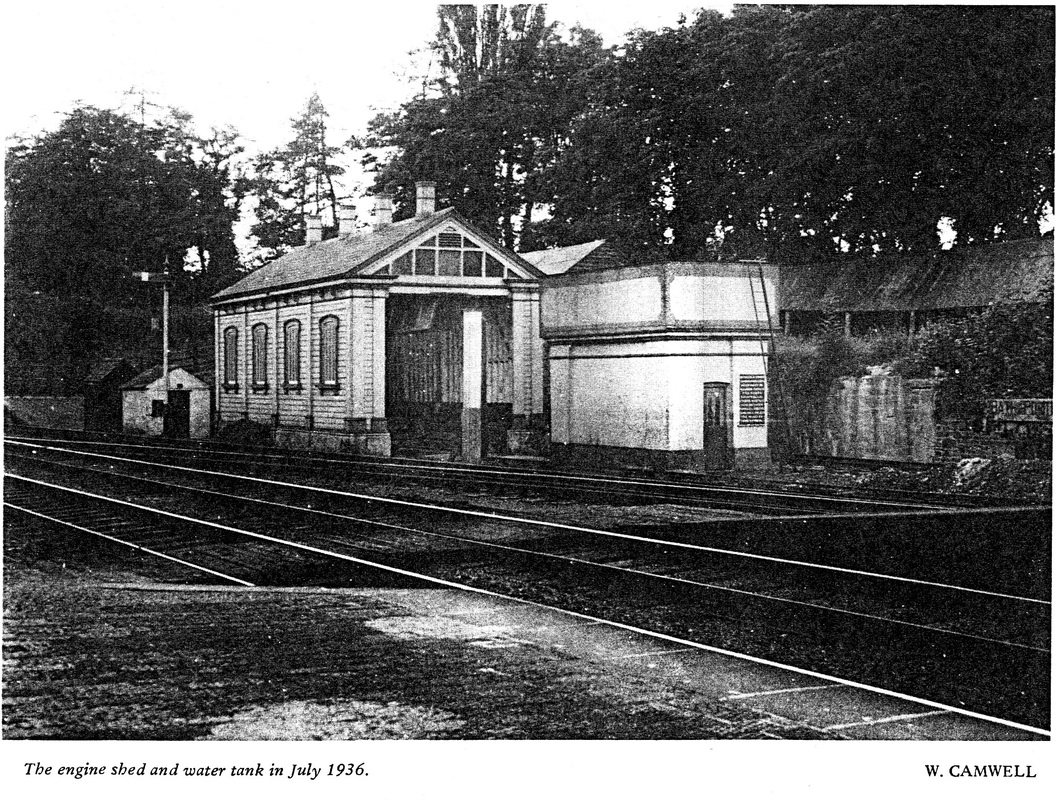

Engine Shed and Water Tower

Engine Shed and Water Tower

From the outset it was realised that additional power would be needed to get trains to negotiate the gradient of the Box Tunnel. A shed was built by Thomas Lewis in February 1842 to house an additional engine at a cost of £328.10s and three years later a water supply was incorporated for the engine's steam needs.[26] In 1845 the engine house was depicted at Hill Mead field, close to the road which went to Middlehill.[27] JC Bourne gave a description of the banker engine in 1846, The Box Station is 101¾ miles from London and 5 from Bath. This is at the foot of the Box inclined plane, and the place at which the assistant engine stands in readiness to assist the regular engine; the mail train however, being light, runs up without that assistance.[28]

The banker engine was severely overworked with short-runs and was replaced every week when a different one was sent out from Swindon. The shed closed on 24 February 1919 when engine power had improved sufficiently.[29] But the water tank remained until the station was closed.[30]

John Froud Added

My own view is that the original engine shed was stone built in about 1842, replaced by a timber shed in 1879. This doesn’t accord with Colin Magg’s account and the matter remains uncertain.

The banker engine was severely overworked with short-runs and was replaced every week when a different one was sent out from Swindon. The shed closed on 24 February 1919 when engine power had improved sufficiently.[29] But the water tank remained until the station was closed.[30]

John Froud Added

My own view is that the original engine shed was stone built in about 1842, replaced by a timber shed in 1879. This doesn’t accord with Colin Magg’s account and the matter remains uncertain.

Goods Shed

This building was much more than just storage. It was a covered area where goods hauled on the railway could be unloaded under cover for local delivery on horse drawn carts or motor vehicles. Sometimes the rail track ran through the shed which often had a crane nearby. At Box the rails ran alongside the goods shed. The goods shed was provided in 1877. A crane was provided as well as a loading gauge whereby goods loaded could be checked to confirm they were in gauge before passing onto the main line. The date of demolition of the goods shed is unknown, but thought to be post-war.[31]

It is just possible to make out the goods shed in the photograph below.

This building was much more than just storage. It was a covered area where goods hauled on the railway could be unloaded under cover for local delivery on horse drawn carts or motor vehicles. Sometimes the rail track ran through the shed which often had a crane nearby. At Box the rails ran alongside the goods shed. The goods shed was provided in 1877. A crane was provided as well as a loading gauge whereby goods loaded could be checked to confirm they were in gauge before passing onto the main line. The date of demolition of the goods shed is unknown, but thought to be post-war.[31]

It is just possible to make out the goods shed in the photograph below.

References

[1] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 2002, Hambledon and London, p.136

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 7 October 1841

[3] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.136

[4] Courtesy John Froud

[5] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p. 30)

[6] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[7] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.139

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 24 December 1863; also refer John Froud, Box Station, p.140

[9] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.80

[10] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.141

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 21 December 1882

[12] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.141 and p.149

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 27 April 1899, 24 August 1899, 31 October 1931

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 25 July 1914

[15] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p. 80

[16] Courtesy of Anna Grayson

[17] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.140

[18] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[19] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p. 135

[20] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, p.69

[21] http://www.kentrail.org.uk/tyler_hill_tunnel.htm

[22] http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Thomas_Edward_Milles_Marsh

[23] MC Corfield, A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Wiltshire, 1978, Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society, p.18

[24] Courtesy Anna Grayson.

[25] See picture John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.146. John added that there is a great example in a photo at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Brunel_bridge_rail.jpg

[26] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.127 and John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.136

[27] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[28] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.134

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.292

[30] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[31] Courtesy John Froud

[1] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 2002, Hambledon and London, p.136

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 7 October 1841

[3] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.136

[4] Courtesy John Froud

[5] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p. 30)

[6] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[7] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.139

[8] The Bath Chronicle, 24 December 1863; also refer John Froud, Box Station, p.140

[9] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.80

[10] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.141

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 21 December 1882

[12] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.141 and p.149

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 27 April 1899, 24 August 1899, 31 October 1931

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 25 July 1914

[15] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p. 80

[16] Courtesy of Anna Grayson

[17] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.140

[18] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[19] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p. 135

[20] Angus Buchanan, Brunel: The Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, p.69

[21] http://www.kentrail.org.uk/tyler_hill_tunnel.htm

[22] http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Thomas_Edward_Milles_Marsh

[23] MC Corfield, A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Wiltshire, 1978, Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society, p.18

[24] Courtesy Anna Grayson.

[25] See picture John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.146. John added that there is a great example in a photo at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Brunel_bridge_rail.jpg

[26] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.127 and John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.136

[27] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[28] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.134

[29] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol IV, p.292

[30] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[31] Courtesy John Froud