The Pybus Family Alan Payne, June 2022

To be buried outside the north door of Box Church, the main entrance to the church, was highly significant, reserved for the most important villagers. So it seems surprising that the tomb of Elizabeth Pybus was located there. This article looks at who the family were and their connection with Box.[1]

Pybus Family

Despite their appearance in the painting, the Pybus forfathers weren’t wealthy and, as a young man, John Pybus senior was sent to Madras, India, to work as a humble clerk for the East India Company. There he met and made friends with Robert Clive (better known as Clive of India). John rose through the company’s ranks to become Chieftain of Masulipatnam, a trading port on the Indian east coast. After 25 years’ service in the country, he had become very wealthy, left India and returned to England with his family. Here he displayed all the trappings of an English nabob (wealthy ex-patriot) buying a town house in Berkeley Square and a country property in Barnet, Hertfordshire. In 1773, he set up a private banking house, Pybus, Hyde, Dorsett & Cockell, at 148 New Bond Street, London, which was inherited by his son after John senior’s death at Cheam, Surrey in 1789.[2]

We can see something about banking and society at this time from a court case in 1783 when a forger William Munroe was sentenced to death for presenting a fraudulent bill of exchange for £10.10s drawn on Pybus’ firm.[3] Munroe was executed by simple hanging on 9 December 1783 for a crime worth under £2,000 in today’s terms. Such was the importance of banking in Georgian society.

John Pybus junior (1754–1808)

John junior was admitted into his father’s firm in 1779, replacing Mr Hyde, an original partner. Shortly before his father’s death, the firm admitted more new partners and in 1785 a new bank was founded called Pybus, Cockell, Pybus & Call, working from premises in Old Bond Street. The family home in Cheam, Surrey, was sold by John Pybus junior in 1803 following his mother’s death and it is conceivable that the new firm was undergoing a financial downturn at that time.

The characters in the family were described by Mr Russell, John junior’s tutor in 1778: Mr Pybus (senior) and son are partners in a Bankers shop in Bond Street. The former struggles incessantly with an asthma and other disorders, which frequently renders his life doubtful for four and twenty hours. His son John finds full employment in the shop and has but little leisure for literary pursuits or any other pleasure.

On his death aged 53 on 13 March 1808, John Pybus junior was described with flowing Georgian exaggeration and deference: a man of irreproachable life and of manners most amiable. He was ever dearly beloved by his friends because, to solid worth, he united those conciliating habits which render mankind more disposed to remark and to revere whatsoever is really good in character. His last days like his whole life were an example of patient sweetness and, by throwing new light on the excellence of his disposition, have added to the deep affection of his widow and family and made them more sensible of the magnitude of their loss.[4]

Elizabeth Pybus (1767-1836)

The connection with Box comes from John junior’s wife Elizabeth McDonnell, originally from Southampton. They married in St Georges Church, Hanover Square, Westminster, London, in October 1799 and they lived in London until John’s death.[5] We can’t trace Elizabeth’s circumstances thereafter but it is conceivable that she had an income for life but few assets. The reason for saying this is that in his will of 1808, John junior left all the family paintings, including the headline picture, directly to his dear son John Bryan Pybus.

Despite their appearance in the painting, the Pybus forfathers weren’t wealthy and, as a young man, John Pybus senior was sent to Madras, India, to work as a humble clerk for the East India Company. There he met and made friends with Robert Clive (better known as Clive of India). John rose through the company’s ranks to become Chieftain of Masulipatnam, a trading port on the Indian east coast. After 25 years’ service in the country, he had become very wealthy, left India and returned to England with his family. Here he displayed all the trappings of an English nabob (wealthy ex-patriot) buying a town house in Berkeley Square and a country property in Barnet, Hertfordshire. In 1773, he set up a private banking house, Pybus, Hyde, Dorsett & Cockell, at 148 New Bond Street, London, which was inherited by his son after John senior’s death at Cheam, Surrey in 1789.[2]

We can see something about banking and society at this time from a court case in 1783 when a forger William Munroe was sentenced to death for presenting a fraudulent bill of exchange for £10.10s drawn on Pybus’ firm.[3] Munroe was executed by simple hanging on 9 December 1783 for a crime worth under £2,000 in today’s terms. Such was the importance of banking in Georgian society.

John Pybus junior (1754–1808)

John junior was admitted into his father’s firm in 1779, replacing Mr Hyde, an original partner. Shortly before his father’s death, the firm admitted more new partners and in 1785 a new bank was founded called Pybus, Cockell, Pybus & Call, working from premises in Old Bond Street. The family home in Cheam, Surrey, was sold by John Pybus junior in 1803 following his mother’s death and it is conceivable that the new firm was undergoing a financial downturn at that time.

The characters in the family were described by Mr Russell, John junior’s tutor in 1778: Mr Pybus (senior) and son are partners in a Bankers shop in Bond Street. The former struggles incessantly with an asthma and other disorders, which frequently renders his life doubtful for four and twenty hours. His son John finds full employment in the shop and has but little leisure for literary pursuits or any other pleasure.

On his death aged 53 on 13 March 1808, John Pybus junior was described with flowing Georgian exaggeration and deference: a man of irreproachable life and of manners most amiable. He was ever dearly beloved by his friends because, to solid worth, he united those conciliating habits which render mankind more disposed to remark and to revere whatsoever is really good in character. His last days like his whole life were an example of patient sweetness and, by throwing new light on the excellence of his disposition, have added to the deep affection of his widow and family and made them more sensible of the magnitude of their loss.[4]

Elizabeth Pybus (1767-1836)

The connection with Box comes from John junior’s wife Elizabeth McDonnell, originally from Southampton. They married in St Georges Church, Hanover Square, Westminster, London, in October 1799 and they lived in London until John’s death.[5] We can’t trace Elizabeth’s circumstances thereafter but it is conceivable that she had an income for life but few assets. The reason for saying this is that in his will of 1808, John junior left all the family paintings, including the headline picture, directly to his dear son John Bryan Pybus.

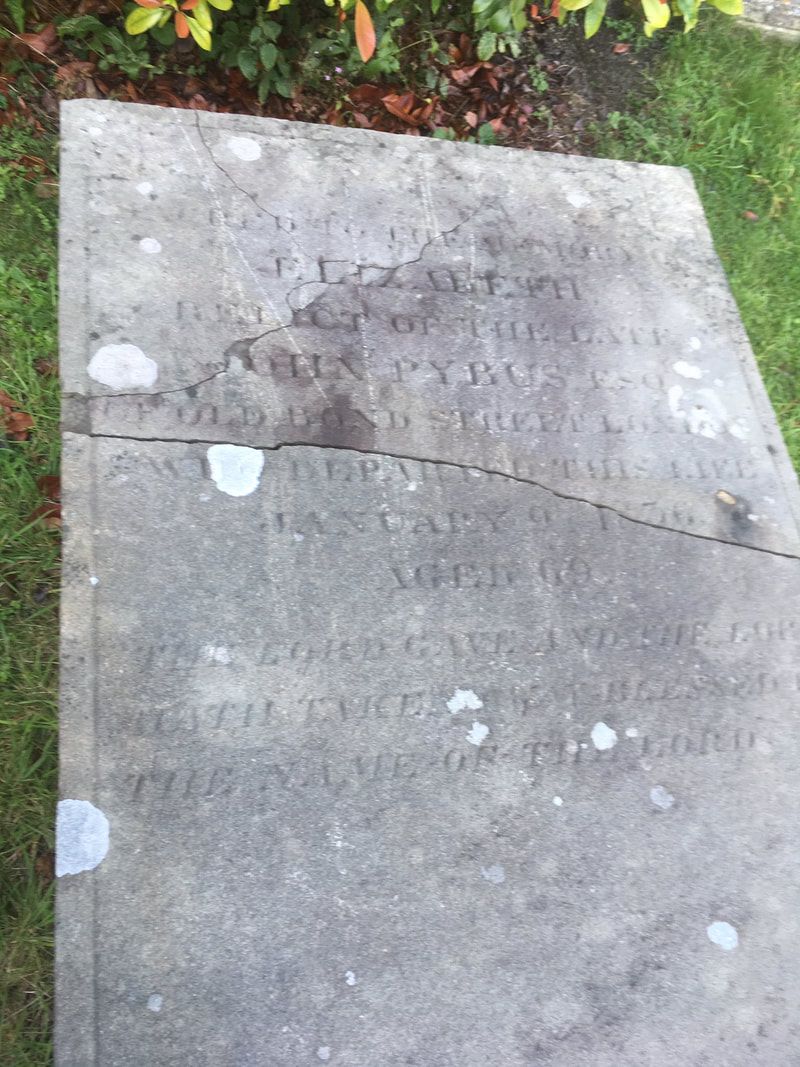

The Pybus chest tomb outside the north door of Box Church (courtesy Carol Payne)

It is probable that Elizabeth was wealthy enough to rent houses for herself and her children during their minority. After they had left home, she probably sought the company of contemporaries and amusement in her life. Bath was always an attraction for widowed ladies. For those who could not afford city prices, a rented property in Box was conveniently nearby. So, Elizabeth moved to Ashley and, on her death in 1836, was buried in Box churchyard. Her tomb chest is both substantial and prominent, outside the main north door entry. The top tablet reads: Erected to the memory of Elizabeth, relict of John Pybus, Esq, of Old Bond Street, London, who departed this life January 9th 1836, aged 69. The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be praised.

Conclusion

The tombstones immediately outside the north door aren’t there by chance. These people were considered worthy of having their memory and status honoured by the congregation as it shuffled in and out of the church. To secure these spots, other bodies were interred and buried elsewhere. Now they have been trapped in a time capsule but, as this article shows, tombs and statues reflect just a moment in time. The Pybus family isn't significant in the story of our village and its importance in national events has long since diminished, if it ever existed.

The tombstones immediately outside the north door aren’t there by chance. These people were considered worthy of having their memory and status honoured by the congregation as it shuffled in and out of the church. To secure these spots, other bodies were interred and buried elsewhere. Now they have been trapped in a time capsule but, as this article shows, tombs and statues reflect just a moment in time. The Pybus family isn't significant in the story of our village and its importance in national events has long since diminished, if it ever existed.

References

[1] The information about the painting and the history of the Pybus family is indebted to Emma Lauze, 2014, on-line at: https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/a-nabobs-return-the-pybus-conversation-piece-by-nathaniel-dance-2/

[2] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 July 1789

[3] The Digital Panopticon William Munro, Life Archive ID obpt17831029-32-defend497 (https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpt17831029-32-defend497).

[4] London Morning Post, 17 March 1808

[5] The Hampshire Telegraph, 28 October 1799

[1] The information about the painting and the history of the Pybus family is indebted to Emma Lauze, 2014, on-line at: https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/a-nabobs-return-the-pybus-conversation-piece-by-nathaniel-dance-2/

[2] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 July 1789

[3] The Digital Panopticon William Munro, Life Archive ID obpt17831029-32-defend497 (https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpt17831029-32-defend497).

[4] London Morning Post, 17 March 1808

[5] The Hampshire Telegraph, 28 October 1799