This is a story that has been common in Box for generations of younger sons: how to enter into farming with limited capital and little or no inheritance. Mike tells how he did it in the second half of the twentieth century by hard work, renting poor land and inadequate housing and the creativity to take advantage of opportunities as they arose.

Born in Forbes Fraser Hospital Bath England 9th August 1943, the youngest of three boys, Bryan eight years older than me and Roger four years older, I was a disappointment to my father the moment I was born - I should have been a baby girl. I came home to Kingsdown Farm, next to Kingsdown Golf Course, on the hill above Box, five miles east of Bath. The family have always been involved with the farming industry.

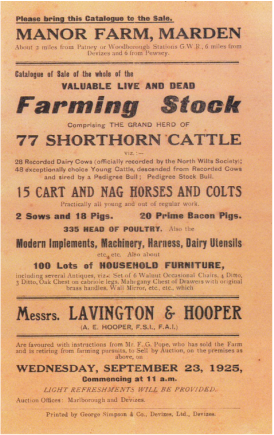

Sale Catalogue from 1926

Sale Catalogue from 1926

Pope Family

Grandfather Pope, Fredrick George Pope (born 1882, died 1954) farmed at Manor Farm, Marden, Devizes, Wiltshire, 500 acres running from Marden village to the edge of Salisbury Plain (the army training area). He married Mary Matilda Wells, my grandmother in 1911.

He sold that farm in 1926 and joined a group of farmers and businessmen that sailed to South Africa and Rhodesia to study the potential of doing business there and to emigrate if they liked it. In fact he returned home to retire at the age of 43 and bring up seven children.

My father, James Alfred Pope (born 30th August 1912, died 1992) was the only one of the seven children to go back into farming.

He started at Norbin Barton Farm, South Wraxall, a rented farm of 122 acres. In 1943 he moved to Kingsdown Farm; soon Lodge Farm and Closes Farm were added, a total of 360 rented acres. He married Kathleen Gladys Webb in 1935.

Grandfather Pope, Fredrick George Pope (born 1882, died 1954) farmed at Manor Farm, Marden, Devizes, Wiltshire, 500 acres running from Marden village to the edge of Salisbury Plain (the army training area). He married Mary Matilda Wells, my grandmother in 1911.

He sold that farm in 1926 and joined a group of farmers and businessmen that sailed to South Africa and Rhodesia to study the potential of doing business there and to emigrate if they liked it. In fact he returned home to retire at the age of 43 and bring up seven children.

My father, James Alfred Pope (born 30th August 1912, died 1992) was the only one of the seven children to go back into farming.

He started at Norbin Barton Farm, South Wraxall, a rented farm of 122 acres. In 1943 he moved to Kingsdown Farm; soon Lodge Farm and Closes Farm were added, a total of 360 rented acres. He married Kathleen Gladys Webb in 1935.

|

My father was very much a livestock farmer, breeding animals was his expertise. The farming consisted of a dairy herd with the rearing of beef animals, out-door pig units, breeding pigs to 8-10 weeks and selling them as weaners, and about 60 or 80 sheep.

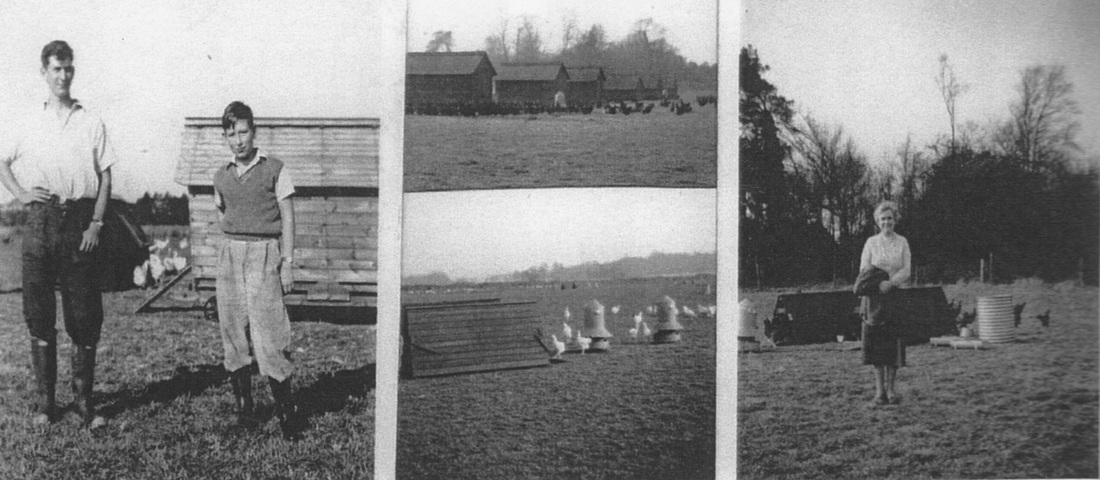

The main enterprise was the hatchery. About 100,000 chicks a year were bred and sent all over the country. The poultry were kept in small units across the fields (free range). However, by 1963 this method was too old-fashioned to compete and was sold. Left: Grandfather and grandmother and children, Jim, Una, Bryan, Gene, Sarah, Tom and Fred. |

Dad never came on holiday. Mum always took my two elder brothers and me to Crowborough where mum's dad and sister, Dorothy, lived in a big house and garden called Mount Hisalick.

Dad's holiday was going on official pheasant shoots as much as twice a week, one at Wintersloe, near Stonehenge. The pheasants were hatched and reared at Kingsdown Farm. Monday evenings were spent sexing chickens with my uncle Fred in the hatchery. Then, on Tuesday mornings, boxing the chickens and my brother and I taking them down to Box Station for distribution all over the country.

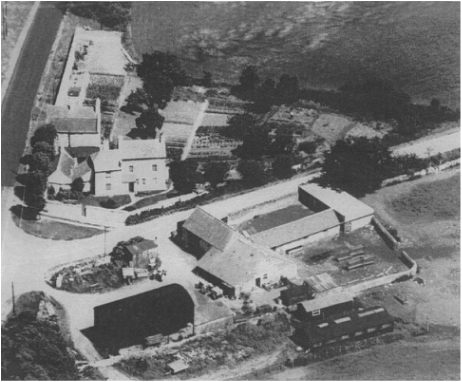

Right: Aerial view of Kingsdown Farm

Below: The free-range poultry units at Kingsdown Farm: Left me with my brother Roger; and Right: my mother.

Dad's holiday was going on official pheasant shoots as much as twice a week, one at Wintersloe, near Stonehenge. The pheasants were hatched and reared at Kingsdown Farm. Monday evenings were spent sexing chickens with my uncle Fred in the hatchery. Then, on Tuesday mornings, boxing the chickens and my brother and I taking them down to Box Station for distribution all over the country.

Right: Aerial view of Kingsdown Farm

Below: The free-range poultry units at Kingsdown Farm: Left me with my brother Roger; and Right: my mother.

|

The Early Years

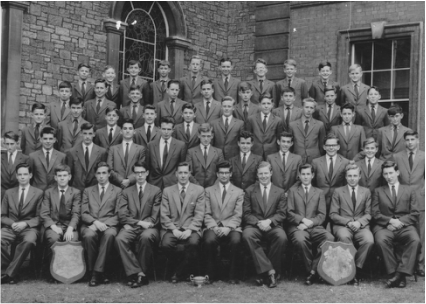

My first school was Miss Hulbert's Prep School, in Trowbridge, Wiltshire and at five years of age I boarded from Mondays to Fridays. I spent most of my time there in the loft for misbehaving. When I was eight to ten years old I went to Cannings College, Grosvenor, Bath. At eleven years I went to Colston's School, Bristol, the fifth Pope to go there. I was never a very academic schoolboy. I could never see the point of most of the subjects and the certificates for them. As I only had intentions of leaving school and going farming, the certificates seemed pointless; how wrong I was. |

Rugby was my best sport. I achieved my first 15 rugby colours while only in the Upper Fifth. I was selected as one of only two players from the school to play for Bristol Public and Grammar schools team, which played at the Memorial Ground Bristol (the home of Bristol Rugby). I left school at 16 so never got to the sixth form.

A Young Farmer

After school I started working for my father on the farm. My job was with the poultry and pigs. I have never liked milking cows. The farm did have about 80 to 90 acres of arable land, harvested with a 6 or 8 foot combine harvester. The grain was collected in very large sacks which weighed 2 hundred weight. You were very tired at the end of every day when you had to load flat trailers with these heavy sacks and then unload them.

In 1963 we had one of the worst snowfalls in living memory. It snowed on Boxing Day; by the next morning nothing could move on the roads. I had to walk through six foot snow drifts to Norbin Barton Farm one mile away to help with the milking. Cowman Tony Young and I never finished till 2pm when we managed to get the milk in churns on a tractor and trailer to the creamery at Staverton, three to four miles away. Then we started milking again. The roads stayed blocked for months, the snow never thawed, and everything had to be done with two tractors going everywhere together to pull each other out as you were always getting stuck.

The pigs were all outside and very difficult to keep going; everything kept freezing up. It was March before the weather allowed us to clear up the disaster. Since then, we have never had a winter anywhere near that year. By the end of the year the poultry were sold at an auction at Norbin Barton Farm. It was a good auction and we got out just in time as the next year the poultry industry took a dive.

My father and I spent more and more time arguing about how the farm should be run. The farm was becoming very old-fashioned, with old men and very old machines and with small, inefficient livestock units. Everything was very labour intensive; machines were a dirty word with my father. My brothers had long since left home. My father had set them up on their own farms. Bryan was farming near Taunton, and Roger was farming near Castle Combe.

After school I started working for my father on the farm. My job was with the poultry and pigs. I have never liked milking cows. The farm did have about 80 to 90 acres of arable land, harvested with a 6 or 8 foot combine harvester. The grain was collected in very large sacks which weighed 2 hundred weight. You were very tired at the end of every day when you had to load flat trailers with these heavy sacks and then unload them.

In 1963 we had one of the worst snowfalls in living memory. It snowed on Boxing Day; by the next morning nothing could move on the roads. I had to walk through six foot snow drifts to Norbin Barton Farm one mile away to help with the milking. Cowman Tony Young and I never finished till 2pm when we managed to get the milk in churns on a tractor and trailer to the creamery at Staverton, three to four miles away. Then we started milking again. The roads stayed blocked for months, the snow never thawed, and everything had to be done with two tractors going everywhere together to pull each other out as you were always getting stuck.

The pigs were all outside and very difficult to keep going; everything kept freezing up. It was March before the weather allowed us to clear up the disaster. Since then, we have never had a winter anywhere near that year. By the end of the year the poultry were sold at an auction at Norbin Barton Farm. It was a good auction and we got out just in time as the next year the poultry industry took a dive.

My father and I spent more and more time arguing about how the farm should be run. The farm was becoming very old-fashioned, with old men and very old machines and with small, inefficient livestock units. Everything was very labour intensive; machines were a dirty word with my father. My brothers had long since left home. My father had set them up on their own farms. Bryan was farming near Taunton, and Roger was farming near Castle Combe.

|

I was chairman of the Trowbridge Young Farmers Club which was very active at this time, with thirty to forty members aged between 16 and 25.

One of the things we were very good at was tug-of-war. We were fortunate to have at that time a very large, strong and fit team. I had the team training at Kingsdown Farm. We used to tie the rope to the back of dad's David Brown tractor, and when we pulled perfectly together the tractor would slip back over a gear. Dad was never sure what damage this was doing to the tractor. Left: Trowbridge Young Farmers |

As we got better I asked John Roberts (captain of Bath Rugby Team, director of Wiltshire Farmers and resident at The Grove, Ashley) if we could come down to their training ground one evening, and have eight of his forwards give us a competitive pull. On the first pull we ran away with them and, much to their disgust and embarrassment, we had to ask them to put another two forwards on their side to give us a decent pull.

The team was never beaten, and we went over the county to shows and the opposition became top Army and RAF teams. The Wiltshire Police went to great lengths at North Bradley one Saturday afternoon. They failed to take us past two straight pulls. We were awarded a small barrel of beer which we consumed with great relish. We then realized we had to get in our cars and drive home with a lot of unhappy policemen around.

The team was never beaten, and we went over the county to shows and the opposition became top Army and RAF teams. The Wiltshire Police went to great lengths at North Bradley one Saturday afternoon. They failed to take us past two straight pulls. We were awarded a small barrel of beer which we consumed with great relish. We then realized we had to get in our cars and drive home with a lot of unhappy policemen around.

To University in America

At the age of 21 I applied for a scholarship to study farming at the University of Minnesota, USA. I had to go to London for the interviews, and much to my father's surprise was selected for the university programme.

Within a week I was on the Queen Elizabeth, sailing for America. Arriving in New York, sailing past the Statue of Liberty, docking alongside the skyscrapers had to be the best possible way of arriving. In total there were 45,000 students at the University of Minnesota. I enrolled on a 17 credit course including economics, soil science, gas & arc welding and a very difficult course on cattle and pig artificial insemination.

Before starting the course I travelled via Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma down to New Mexico, the Grand Canyon and San Francisco. I drove up on the Alaskan Highway through the Rockies of British Columbia to Yukon at minus 40 degrees in the middle of winter and on to Anchorage, Alaska. The temperature at only zero degrees felt like summer.

I found the artificial breeding course very difficult. Fortunately Professor Graham, my lecturer, asked me to work in his laboratory - he was a top man in the US in this subject. I found this very interesting and it helped me do a great deal better on the course. I managed to pass all my subjects and then went to Wisconsin to study how the Tristate Breeders Company operated using artificial insemination for cattle and pigs.

When the course finished, I returned home. I decided to get in touch with Unilever (Walls Foods parent company) to use the knowledge I had gained in artificial insemination (AI). They were keen to take me on as they were just starting a new centre for AI work on pigs at High Wycombe. I helped with the hybrid breeding program which entailed a lot of driving to selected farms all over the south of the England.

While at High Wycombe the wanderlust struck again. So in February 1967 I went to Australia House in London and asked to emigrate to Perth, Australia. I was to become a £10 pommy immigrant.

At the age of 21 I applied for a scholarship to study farming at the University of Minnesota, USA. I had to go to London for the interviews, and much to my father's surprise was selected for the university programme.

Within a week I was on the Queen Elizabeth, sailing for America. Arriving in New York, sailing past the Statue of Liberty, docking alongside the skyscrapers had to be the best possible way of arriving. In total there were 45,000 students at the University of Minnesota. I enrolled on a 17 credit course including economics, soil science, gas & arc welding and a very difficult course on cattle and pig artificial insemination.

Before starting the course I travelled via Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma down to New Mexico, the Grand Canyon and San Francisco. I drove up on the Alaskan Highway through the Rockies of British Columbia to Yukon at minus 40 degrees in the middle of winter and on to Anchorage, Alaska. The temperature at only zero degrees felt like summer.

I found the artificial breeding course very difficult. Fortunately Professor Graham, my lecturer, asked me to work in his laboratory - he was a top man in the US in this subject. I found this very interesting and it helped me do a great deal better on the course. I managed to pass all my subjects and then went to Wisconsin to study how the Tristate Breeders Company operated using artificial insemination for cattle and pigs.

When the course finished, I returned home. I decided to get in touch with Unilever (Walls Foods parent company) to use the knowledge I had gained in artificial insemination (AI). They were keen to take me on as they were just starting a new centre for AI work on pigs at High Wycombe. I helped with the hybrid breeding program which entailed a lot of driving to selected farms all over the south of the England.

While at High Wycombe the wanderlust struck again. So in February 1967 I went to Australia House in London and asked to emigrate to Perth, Australia. I was to become a £10 pommy immigrant.

Emigrating to Australia

I flew out to Perth at the end of March. I had been given some wonderful introductions to people in Australia by Douglas Leese, who lived in South Wraxall Manor, such as the Managing Director of Chamberlain Industries Australia, the makers of Chamberlain Tractors who were about to be taken over by John Deere. The emigrants were all put in hotels and given bed and breakfast free for the first week. I was booked into a very posh hotel by Chamberlain Industries but, when I found I had to pay for it, I soon moved back to the free immigrants hotel.

While I was being shown around I was introduced to Jeff Lindsay, who offered me a job working for them and on the way to Perth I was dropped off at Calingeri 90 miles north of Perth, which was the Lindsay farm. The farm was large for the area, about 14,000 acres, with 14,000 sheep and 7,000 to 8,000 acres of wheat. The labour force most of the time was Jeff Lindsay, his son Ross, myself and Max, a hired hand. At planting, harvesting, and shearing the shearing teams would come and help out. The size of their machinery on the farm was very large. Compared with England everything was done on a large scale, which I found very enjoyable.

The planting season soon arrived. The disc ploughs were worked twenty four hours a day and I had to learn how to go round the fields in the dark. The paddocks were so large I would get lost. When the ground was worked ready for planting, the seed drills for planting were rigged out with lights everywhere to keep planting all day and all through the night.

When I asked how much my father might help me if I stayed farming in Australia, I was surprised to find the answer was Nothing. He felt the only way he could help was if I came home and joined him in a partnership. The idea of him or my brothers joining me in Australia, which had been talked about, had also disappeared from the equation.

It was a hard decision to make as I never used to get on with my father. I did know that Norbin Barton Farm, which was rented by my father, could be bought. That, I thought, might create the starting blocks I needed to get going in farming. Having made the decision to return home, my father told me I had a week to get home.

I had to go to the Australian High Commission to have my passport stamped to allow me to leave. Before they would do that I had to pay them back the cost of sending me to Australia as I was returning in less than two years. I was very sad to be leaving Australia.

I flew out to Perth at the end of March. I had been given some wonderful introductions to people in Australia by Douglas Leese, who lived in South Wraxall Manor, such as the Managing Director of Chamberlain Industries Australia, the makers of Chamberlain Tractors who were about to be taken over by John Deere. The emigrants were all put in hotels and given bed and breakfast free for the first week. I was booked into a very posh hotel by Chamberlain Industries but, when I found I had to pay for it, I soon moved back to the free immigrants hotel.

While I was being shown around I was introduced to Jeff Lindsay, who offered me a job working for them and on the way to Perth I was dropped off at Calingeri 90 miles north of Perth, which was the Lindsay farm. The farm was large for the area, about 14,000 acres, with 14,000 sheep and 7,000 to 8,000 acres of wheat. The labour force most of the time was Jeff Lindsay, his son Ross, myself and Max, a hired hand. At planting, harvesting, and shearing the shearing teams would come and help out. The size of their machinery on the farm was very large. Compared with England everything was done on a large scale, which I found very enjoyable.

The planting season soon arrived. The disc ploughs were worked twenty four hours a day and I had to learn how to go round the fields in the dark. The paddocks were so large I would get lost. When the ground was worked ready for planting, the seed drills for planting were rigged out with lights everywhere to keep planting all day and all through the night.

When I asked how much my father might help me if I stayed farming in Australia, I was surprised to find the answer was Nothing. He felt the only way he could help was if I came home and joined him in a partnership. The idea of him or my brothers joining me in Australia, which had been talked about, had also disappeared from the equation.

It was a hard decision to make as I never used to get on with my father. I did know that Norbin Barton Farm, which was rented by my father, could be bought. That, I thought, might create the starting blocks I needed to get going in farming. Having made the decision to return home, my father told me I had a week to get home.

I had to go to the Australian High Commission to have my passport stamped to allow me to leave. Before they would do that I had to pay them back the cost of sending me to Australia as I was returning in less than two years. I was very sad to be leaving Australia.

|

Back To Work In The UK

My parents met me at Heathrow airport and it was straight down the M4 home. I started working on the farm immediately. The small fields and small machines took some getting used to after Australia. Dad was still using an 8 foot combine harvester with a man stood on the side of the combine; his job was to fill large sacks with grain, tie them and slide them down to a chute, and, when there were three sacks, let them fall on the ground. My job now was to stand them up, and, with the help of another man, lift them onto a flat bed trailer, then cart them to a building and unload. I felt I had gone back twenty years in time. |

I

could see it was going to be very hard getting my father to be more

efficient. I even had to go back to milking cows. Most of my friends had

got married and had children since I had been away and I was getting a

bit old for Young Farmers Club. So with a friend, George Gifford, a

farmer from Thickwood, I went along to the Chippenham Young

Conservatives Club. There I was met by an attractive brunette, who asked

me for money. She has never stopped asking me for money since. This was

Carol George, now Carol Pope, my wife. She was the Membership Secretary

for the Young Conservative Club.

The farm still had too many employees. There was my father and me plus four men: two men milking 80 to 90 cows and no such thing as self-fed silage. Dad had an open clamp 400 metres from the cattle yards, where you had to back a trailer up to the face, and with a silage knife cut a line 6 feet back. You stank and your back was breaking. At harvest time, the straw was baled in small four-foot bales, and then loaded by hand until the load got high, then you used the prongs. The loaded trailers were taken to the barns where they were unloaded into an elevator and transported up into the barns to be stacked.

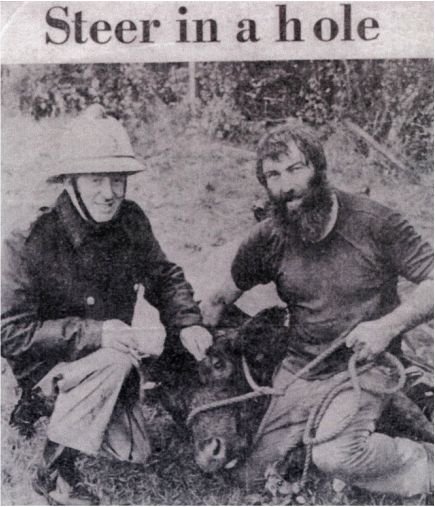

The cattle yards were very old and had to be cleared by prong into the trailers then taken out and dumped in large dung heaps around the fields. Some yards could be cleared with our 75 horsepower David Brown tractor, which had a four foot bucket. Cattle-handling also had to be a wrestling match, with feet getting trodden on, and backs slammed into walls. It was another five years before we got a cattle crush. Dad always used to keep the in-calf heifers in a field at the back of Lodge Farm. The woods were all around this field, which made the flies bad.

The farm still had too many employees. There was my father and me plus four men: two men milking 80 to 90 cows and no such thing as self-fed silage. Dad had an open clamp 400 metres from the cattle yards, where you had to back a trailer up to the face, and with a silage knife cut a line 6 feet back. You stank and your back was breaking. At harvest time, the straw was baled in small four-foot bales, and then loaded by hand until the load got high, then you used the prongs. The loaded trailers were taken to the barns where they were unloaded into an elevator and transported up into the barns to be stacked.

The cattle yards were very old and had to be cleared by prong into the trailers then taken out and dumped in large dung heaps around the fields. Some yards could be cleared with our 75 horsepower David Brown tractor, which had a four foot bucket. Cattle-handling also had to be a wrestling match, with feet getting trodden on, and backs slammed into walls. It was another five years before we got a cattle crush. Dad always used to keep the in-calf heifers in a field at the back of Lodge Farm. The woods were all around this field, which made the flies bad.

Facing Up To Married Life

I was not very happy on the farm. Fortunately I met Carol in October 1968 and the following June we got engaged, so my car got to know the road to 19 King Alfred Street, Chippenham, Wiltshire, very well indeed. I first asked her out while at the White Hart Pub, in Ford. This was to go to the Avon Vale Hunt Ball. I thought this would impress her, I think things went down hill after that.

I was not very happy on the farm. Fortunately I met Carol in October 1968 and the following June we got engaged, so my car got to know the road to 19 King Alfred Street, Chippenham, Wiltshire, very well indeed. I first asked her out while at the White Hart Pub, in Ford. This was to go to the Avon Vale Hunt Ball. I thought this would impress her, I think things went down hill after that.

|

We decided to get married the following March in Chippenham, and we would live at Norbin Barton Farm. Unfortunately the farmhouse there had not been lived in for three years and needed a lot of renovations and modernizing. So from getting engaged to getting married we had to work very hard on the house. It even had to have a complete new roof. In fact the place was gutted completely, but, with the help of builders and our own efforts we were just finished by March 14th 1970.

We were married at St Paul's Church, Chippenham. The reception was at the Selwyn Hall, Box. I was convinced my friends would give me a hard time, as I had done some terrible things to them, so I planned a special escape using my uncle Fred to whisk us away and, if anyone followed, one of our tractor drivers was waiting to block the road with his tractor. We made our way to London. Three days later I was not very popular as I wanted to return home to get on with some spring barley planting. George James Pope arrived 9 month later. I don't think my father-in-law, Tom George, could get over the shock. In 1970 both his daughters got married and he became a grandfather in the November. We made him suddenly feel old. |

It was soon after this that we were in negotiations to buy Norbin Barton Farm. Dad had in fact been offered the farm when I was in the USA and had turned it down. We were lucky no one else bought it. Twelve months later we were asked if we wanted to buy, but this time the price was four times what he had originally been asked. This was partly because we had made such a good job of doing up the farmhouse. I arranged a loan at the bank and put all my money into the deal.

Farming on My Own Account

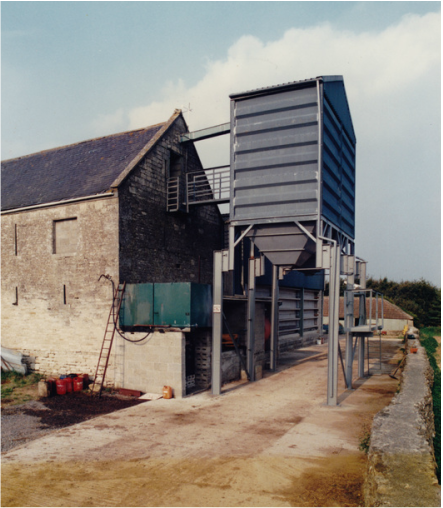

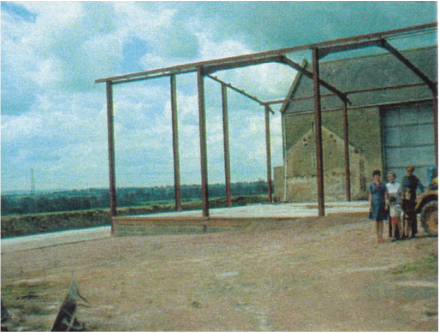

All this time I was trying to modernize the farm but it was painful. It wasn't until we were able to lease Hatt Farm that I told my father I was about to break away and be independent. He told me I could take over the lot and he would wash his hands of it. This allowed me to concentrate on the arable farming, and we finally got rid of that bagger combine harvester, and introduced a decent bulk handling system. It was such a joy to have that 12-foot Class combine harvester. It was also the first combine harvester on the farm to have a driver's cab to protect the driver.

All this time I was trying to modernize the farm but it was painful. It wasn't until we were able to lease Hatt Farm that I told my father I was about to break away and be independent. He told me I could take over the lot and he would wash his hands of it. This allowed me to concentrate on the arable farming, and we finally got rid of that bagger combine harvester, and introduced a decent bulk handling system. It was such a joy to have that 12-foot Class combine harvester. It was also the first combine harvester on the farm to have a driver's cab to protect the driver.

I converted the old buildings at Hatt Farm. In the big stone barn I built a grain store, with ten grain bins, a drive over grain pit, with 50 tonne an hour elevator and conveyor system. This was my pride and joy for a while, but it soon became totally inadequate for the extra acres I was taking on. So two years later I built a new on floor grain store, with drying air ducts in the floor. It was as we were putting the grain bins in the stone barn, that Edward Keith Pope was born January 1973.

One of my less clever ideas was to convert some other old buildings at Hatt Farm to pig farrowing cubicles, and weaner pens in some old cart sheds, thinking this would be a better system than farrowing out in the fields. Very soon I found out just how smelly pigs can be. The smell in the house was awful, even clean clothes smelled of pigs. The flies, which were normally non-existent, became intolerable.

My pig food supplier, Paul's Agriculture, were keen to supply me with boars for breeding, but their offspring all had twisted noses (rhinitis), a disease they had inherited from the boars. Paul's Agriculture compensated me for the whole place to be cleaned and disinfected. All the pigs on the farm had to be sold. I thought this a good time to get out of pigs altogether, and concentrate on the arable side of the farming.

My pig food supplier, Paul's Agriculture, were keen to supply me with boars for breeding, but their offspring all had twisted noses (rhinitis), a disease they had inherited from the boars. Paul's Agriculture compensated me for the whole place to be cleaned and disinfected. All the pigs on the farm had to be sold. I thought this a good time to get out of pigs altogether, and concentrate on the arable side of the farming.

A year later our senior cowman, Harry Perry retired, so I was delighted to sell the cows, and pull lots of fences up at Norbin Barton Farm, and produce my first 100 acre field there. With only a 100 beef animals to rear and fatten, the farm was finally becoming efficient and the labour force now at a much more realistic level: just myself, Bill Ayliff and Tony Young.

It was a good time for farming with the UK joining the European Common Market. Prices increased considerably every year and I started looking for more land where I could grow arable crops. The first addition was South Wraxall Manor Farm. Douglas Leese (the man who gave me all my contacts in Australia), had become disillusioned with the farm. He was not a farmer, and did not want to be bothered by the farm. I left him fifty acres around the Manor House, and ploughed up the rest, and paid him a rent every July. The machinery on the farm was not really up to the job as the acreage got larger, so we worked very long hours until the money was there to upgrade to better equipment.

It was a good time for farming with the UK joining the European Common Market. Prices increased considerably every year and I started looking for more land where I could grow arable crops. The first addition was South Wraxall Manor Farm. Douglas Leese (the man who gave me all my contacts in Australia), had become disillusioned with the farm. He was not a farmer, and did not want to be bothered by the farm. I left him fifty acres around the Manor House, and ploughed up the rest, and paid him a rent every July. The machinery on the farm was not really up to the job as the acreage got larger, so we worked very long hours until the money was there to upgrade to better equipment.

Nineteen seventy six was the summer of the big drought. The harvest started very early in July, and the crops died rather than ripened. The yields needless to say were very poor: some spring barley on the top of the farm were the worst, and the straw left behind the combine was in blobs rather than the usual swaths. In those days, burning the stubble fields was the common practice. Each field had a firebreak cultivated around it, but that year everything was so dry.

A field-burn at Longsplatt, at the top of Hatt Farm, jumped the firebreak and burnt everything all the way to Hatt Farm. Luckily the fire went round the house and farm buildings, stopping at the road on the farm entrance. Harvesting was all over by the beginning of August, quite unheard-of, so we decided to go to Devon for a holiday something we had never done before in August.

A field-burn at Longsplatt, at the top of Hatt Farm, jumped the firebreak and burnt everything all the way to Hatt Farm. Luckily the fire went round the house and farm buildings, stopping at the road on the farm entrance. Harvesting was all over by the beginning of August, quite unheard-of, so we decided to go to Devon for a holiday something we had never done before in August.

Life As A Farming Co-operative Director

During the late 1970's I became a director of North Wiltshire Cereals, part of Group Cereal Services of Marlborough, a co-operative marketing £36 million pounds of cereals a year. In 1978 I became chairman of the Bradford on Avon Farmers Discussion Club. I can remember one meeting at Westonbirt Arboretum. We were taken round by David Rice, the county forester, also present were the Ministry of Agriculture grants administrators. It was a very successful day, everyone went back to their farms and planted many trees with the help of government money.

I was made Chairman of the North Wiltshire Quality Wheat Group in 1979, and was responsible for organizing trial plots on members farms all over the county. This proved very difficult and I needed help from the Ministry of Agriculture and Lackham Agricultural College. They provided me with students to help gather all the field data then got involved with growing the Wiltshire cereal plots at the Royal Agriculture Show Grounds, Stoneleigh, in Warwickshire.

During the late 1970's I became a director of North Wiltshire Cereals, part of Group Cereal Services of Marlborough, a co-operative marketing £36 million pounds of cereals a year. In 1978 I became chairman of the Bradford on Avon Farmers Discussion Club. I can remember one meeting at Westonbirt Arboretum. We were taken round by David Rice, the county forester, also present were the Ministry of Agriculture grants administrators. It was a very successful day, everyone went back to their farms and planted many trees with the help of government money.

I was made Chairman of the North Wiltshire Quality Wheat Group in 1979, and was responsible for organizing trial plots on members farms all over the county. This proved very difficult and I needed help from the Ministry of Agriculture and Lackham Agricultural College. They provided me with students to help gather all the field data then got involved with growing the Wiltshire cereal plots at the Royal Agriculture Show Grounds, Stoneleigh, in Warwickshire.

Farming Developments

I was approached to farm Hazelbury Manor land at this time. Ian Pollard was a businessman rather than a farmer, spending more money than he was earning on the farm. Most of the land was mountain goat country, so a friend of mine put cattle there and I ploughed up what I could. I never had any trouble getting the men to work there because Mrs Pollard had an aversion to wearing clothes, and the tales of what was seen at Hazelbury Manor were very entertaining.

A frightening moment at that place was when I had put a fire break round a field of straw left after combining and then tried to burn it off, which was common practice then (not allowed now). The problem was it had taken so long to burn that it was getting dark. As this field was on a steep hill at the side of the village, the whole place suddenly became illuminated. People were calling the fire service, and a considerable amount of panic was created. My neighbouring farmer, Tim Barton, came to see what was going on, and his father, Roger Barton, rushed back thinking it may have been one of his fields going up in flames.

During the autumn of 1979 we cleared Chesland Wood, part of Norbin Barton Farm. This was registered as an ancient woodland. David Rice the county forester planned the replanting for me, he decided we should grow beech, Norway Maple and wild cherry. Three thousand, five hundred trees were planted; most of the old wood was cut up for log fires and delivered to private homes.

The 1980s

One of the first things I can remember when being made a director of North Wiltshire Cereals, was a decision to buy our own computer. We were going to spend £65,000 (which became over £100,000) to buy what turned out to be the last of the computer dinosaurs, the old number crunchers. It was big, seven metres long by two metres high, wheels spinning everywhere. We even had to build a new wing on the offices to house it. It was already becoming obsolete by the time it was completed, and it was obvious we had spent a fortune and gone backwards

I was approached to farm Hazelbury Manor land at this time. Ian Pollard was a businessman rather than a farmer, spending more money than he was earning on the farm. Most of the land was mountain goat country, so a friend of mine put cattle there and I ploughed up what I could. I never had any trouble getting the men to work there because Mrs Pollard had an aversion to wearing clothes, and the tales of what was seen at Hazelbury Manor were very entertaining.

A frightening moment at that place was when I had put a fire break round a field of straw left after combining and then tried to burn it off, which was common practice then (not allowed now). The problem was it had taken so long to burn that it was getting dark. As this field was on a steep hill at the side of the village, the whole place suddenly became illuminated. People were calling the fire service, and a considerable amount of panic was created. My neighbouring farmer, Tim Barton, came to see what was going on, and his father, Roger Barton, rushed back thinking it may have been one of his fields going up in flames.

During the autumn of 1979 we cleared Chesland Wood, part of Norbin Barton Farm. This was registered as an ancient woodland. David Rice the county forester planned the replanting for me, he decided we should grow beech, Norway Maple and wild cherry. Three thousand, five hundred trees were planted; most of the old wood was cut up for log fires and delivered to private homes.

The 1980s

One of the first things I can remember when being made a director of North Wiltshire Cereals, was a decision to buy our own computer. We were going to spend £65,000 (which became over £100,000) to buy what turned out to be the last of the computer dinosaurs, the old number crunchers. It was big, seven metres long by two metres high, wheels spinning everywhere. We even had to build a new wing on the offices to house it. It was already becoming obsolete by the time it was completed, and it was obvious we had spent a fortune and gone backwards

The farm was continuing to grow. One Friday evening in early August 1981 my very good friend, Maurice Baker, came to see if I would be interested in jointly buying a farm at Sutton Benger, near Chippenham. The farm had gone to auction and failed.

I looked at it with Bill Ayliff, my main tractor driver, who would have to do most of the work. It was a 265 acre all arable farm, with a modern, large grain store and general store. We decided that, although it was 13 miles away, the farm would be no problem to operate. I saw my bank manager on Monday morning and by 4pm that afternoon the farm was bought.

There were more new activities on other parts of our land and I started tipping at Norbin Barton Farm after we got permission from County Hall. We kept this going for about two years.

As well as being highly profitable, we retrieved a quarry crane from a mine 100 feet under the surface, which was later taken to Pickwick Stone Mine Museum.

Left:Bill Ayliff seen at The Swan pub in 1982 (photo courtesy Trevor Porter).

The mid-1980s was when I had to leave Round Table under their 40 years rule (now 45 years). I automatically joined the follow-on 41 Club. This enabled me to keep going to the international weekends and to continue fundraising for worthwhile causes.

I looked at it with Bill Ayliff, my main tractor driver, who would have to do most of the work. It was a 265 acre all arable farm, with a modern, large grain store and general store. We decided that, although it was 13 miles away, the farm would be no problem to operate. I saw my bank manager on Monday morning and by 4pm that afternoon the farm was bought.

There were more new activities on other parts of our land and I started tipping at Norbin Barton Farm after we got permission from County Hall. We kept this going for about two years.

As well as being highly profitable, we retrieved a quarry crane from a mine 100 feet under the surface, which was later taken to Pickwick Stone Mine Museum.

Left:Bill Ayliff seen at The Swan pub in 1982 (photo courtesy Trevor Porter).

The mid-1980s was when I had to leave Round Table under their 40 years rule (now 45 years). I automatically joined the follow-on 41 Club. This enabled me to keep going to the international weekends and to continue fundraising for worthwhile causes.

My Accident

Nineteen eighty will be a year I will never forget. The year had been going very well and Group Cereal Service (GCS) proposed a very interesting plan to build a new grain terminal at Cowes on the Isle of Wight. I never made it there. On the 1st October 1980 I decided to take out one of the tractors with a power harrow to Norbin Barton Farm to plant wheat. I was in the 100 Acre field which had some stony areas. On one pass I stopped to pick up a large stone, which I transported to the side where I planned to remove it. It was the oldest tractor on the farm and had quite a few problems. I thought about turning off the engine of the tractor but the radiator had started leaking that morning, so to stop it would mean losing even more water. It was the wrong decision to leave it running.

To this day I am surprised I did this, as I was a stickler for safety where the men were concerned, and at this time I was an examiner of students at Lackham Agricultural College, wanting to obtain their various machinery certificates. I always gave them a lecture on machinery safety, and failed any slight infringement. The only way to remove the stone was to put my foot on the side of the machine. My foot slipped, landing between the roller and the spinning tines. After a struggle I fell over the back of the tiller and onto the ground. I thought for a moment that I had got away with it, then something hit the side of me. It was the lower half of my leg. I looked at my right leg and found myself staring at the bottom of my thigh bone.

Thank God I never fainted. I knew if I did I would bleed to death. I squeezed the blood vessels in my leg, and started wriggling my way across the field, under a barbed wire fence, which I got hooked in several times, down the track to Norbin Barton Farm yard and across the concrete yard to the farmhouse. Nobody was in.

I managed to get inside and dial 999. The next few weeks were spent in and out of the operating theatre. I developed an infection which was so bad that I was put by the window with two fans blowing. One day three vicars came to see me and I started to think someone was trying to tell me something. Finally recovery was on its way and I was soon pestering the limb centre in Bristol to make me an artificial leg.

Nineteen eighty will be a year I will never forget. The year had been going very well and Group Cereal Service (GCS) proposed a very interesting plan to build a new grain terminal at Cowes on the Isle of Wight. I never made it there. On the 1st October 1980 I decided to take out one of the tractors with a power harrow to Norbin Barton Farm to plant wheat. I was in the 100 Acre field which had some stony areas. On one pass I stopped to pick up a large stone, which I transported to the side where I planned to remove it. It was the oldest tractor on the farm and had quite a few problems. I thought about turning off the engine of the tractor but the radiator had started leaking that morning, so to stop it would mean losing even more water. It was the wrong decision to leave it running.

To this day I am surprised I did this, as I was a stickler for safety where the men were concerned, and at this time I was an examiner of students at Lackham Agricultural College, wanting to obtain their various machinery certificates. I always gave them a lecture on machinery safety, and failed any slight infringement. The only way to remove the stone was to put my foot on the side of the machine. My foot slipped, landing between the roller and the spinning tines. After a struggle I fell over the back of the tiller and onto the ground. I thought for a moment that I had got away with it, then something hit the side of me. It was the lower half of my leg. I looked at my right leg and found myself staring at the bottom of my thigh bone.

Thank God I never fainted. I knew if I did I would bleed to death. I squeezed the blood vessels in my leg, and started wriggling my way across the field, under a barbed wire fence, which I got hooked in several times, down the track to Norbin Barton Farm yard and across the concrete yard to the farmhouse. Nobody was in.

I managed to get inside and dial 999. The next few weeks were spent in and out of the operating theatre. I developed an infection which was so bad that I was put by the window with two fans blowing. One day three vicars came to see me and I started to think someone was trying to tell me something. Finally recovery was on its way and I was soon pestering the limb centre in Bristol to make me an artificial leg.

Lots of Changes

The harvest in 1991 was quite difficult. Bill Ayliff had left the farm to work for his brother and I missed him greatly. We always worked well together and he proved very hard to replace. I decided to put the whole farm into set-aside and take the land out of production for five years. When the harvest was out of the way, I put the whole farm down to clover, as this would keep the land in good heart for the five years. I only had Tony Young left on the farm now and he kept a small beef unit going at Norbin Barton Farm.

By 1992 dad was having problems. It had started two years before when we had an SOS call from him. When we got to Kingsdown Farm, dad was in the lounge covered in blood. He had fallen in the bedroom the night before and cut his face badly, leaving blood all over the place but he could not get to the phone till the next morning.

The harvest in 1991 was quite difficult. Bill Ayliff had left the farm to work for his brother and I missed him greatly. We always worked well together and he proved very hard to replace. I decided to put the whole farm into set-aside and take the land out of production for five years. When the harvest was out of the way, I put the whole farm down to clover, as this would keep the land in good heart for the five years. I only had Tony Young left on the farm now and he kept a small beef unit going at Norbin Barton Farm.

By 1992 dad was having problems. It had started two years before when we had an SOS call from him. When we got to Kingsdown Farm, dad was in the lounge covered in blood. He had fallen in the bedroom the night before and cut his face badly, leaving blood all over the place but he could not get to the phone till the next morning.

He went to Beechfield House at Batheaston and stayed there until they could not cope with his condition. He then had to go to Chippenham Hospital where he died on 1st May 1992. A very sad time. Dad and I found that, as soon as we were not in conflict over the farm, our relationship improved tremendously and we were really great mates in the end.

At Hatt Farm in April 1992 we were busy getting all the farm machinery cleaned and tidied up for a farm sale. With all the land in set-aside there was no point in keeping the machines just to depreciate, so almost everything went.

At Hatt Farm in April 1992 we were busy getting all the farm machinery cleaned and tidied up for a farm sale. With all the land in set-aside there was no point in keeping the machines just to depreciate, so almost everything went.

To The North Pole

1998 was the year I went to the North Pole. This wonderful experience started very suddenly one Saturday morning in April 1998. David Hempleman-Adams, was planning to walk to the North Pole, and his family were to fly out and meet him. David's brother Mark said he would try and get me on a flight to Canada. That was 12 noon on the Saturday and by 10am Monday morning I was on my way.

Mark had some spare clothes needed to cope with temperatures of minus 50 degrees. The media made our phone very busy, and, as we left Hatt Farm, we drove into a barrage of TV cameras and press. I actually made the evening news that night.

We flew to Calgary, Canada, then on to Edmonton, where we spent the night and caught up with the people congratulating David Hempleman-Adams on his record breaking feat. This was his third attempt to make it to the geographic North Pole. We arrived at Resolute Bay with the temperature at minus 25 degrees.

The base camp very kindly gave up a room, when they heard I had an artificial leg and I found it most interesting having my bed in the control centre. The Press were sending all their newspaper articles and pictures from their lap top computers, which were plugged into the telephone in my room, and arriving instantly in London, and in the papers within hours.

1998 was the year I went to the North Pole. This wonderful experience started very suddenly one Saturday morning in April 1998. David Hempleman-Adams, was planning to walk to the North Pole, and his family were to fly out and meet him. David's brother Mark said he would try and get me on a flight to Canada. That was 12 noon on the Saturday and by 10am Monday morning I was on my way.

Mark had some spare clothes needed to cope with temperatures of minus 50 degrees. The media made our phone very busy, and, as we left Hatt Farm, we drove into a barrage of TV cameras and press. I actually made the evening news that night.

We flew to Calgary, Canada, then on to Edmonton, where we spent the night and caught up with the people congratulating David Hempleman-Adams on his record breaking feat. This was his third attempt to make it to the geographic North Pole. We arrived at Resolute Bay with the temperature at minus 25 degrees.

The base camp very kindly gave up a room, when they heard I had an artificial leg and I found it most interesting having my bed in the control centre. The Press were sending all their newspaper articles and pictures from their lap top computers, which were plugged into the telephone in my room, and arriving instantly in London, and in the papers within hours.

|

Charity Fundraising

Mike has been involved in so many fundraising challenges that it is difficult to list them all or the amount of money he has personally raised for worthy causes. As well as his North Pole venture, here are just a few extracts of his incredible activities. In June 1999 I decided to give myself a challenge on a bicycle but my foot kept slipping off the pedal of an ordinary bike. I solved this by tying my artificial foot to the pedal with a handkerchief. Things went well until the whole of my prosthetic leg fell off. In 2000 I competed in the biggest cycle event in the world with 35,000 other competitors in the Argus Cycle Race in Cape Town organised by 25 South African Rotary Clubs. I completed the whole 80 mile course plus three mountain climbs without putting a foot down until we went over the finishing line. I was delighted to finish the whole route in 22,249th place in a time of under five and a half hours. In 2003 I decided to do a 250 mile cycle ride across Cuba as part of a Douglas Bader charity event held over five days from Havana to Trinidad. In 2006 I cycled from the bottom of Ireland to the top covering 416 miles. |

Perhaps my greatest cycling achievement was in 2004 when I completed 1,007 miles from Landsend to John O'Groats.I was the first above-knee amputee to complete the course and I raised £1,150 for Rotary charities.

Mike's work was recognised in 2005 when he and Carol were invited to a Buckingham Palace Garden Party and by 2006 he was awarded a Rotary Paul Harris Fellowship for raising over £50,000 for charity.

Mike's work was recognised in 2005 when he and Carol were invited to a Buckingham Palace Garden Party and by 2006 he was awarded a Rotary Paul Harris Fellowship for raising over £50,000 for charity.

Family Tree

Grandparents

Fredrick George Pope (1882 - 1954) of Manor Farm, Marden, Devizes married Mary Matilda Wells in 1911

Children: James Alfred, Una, Bryan, Gene, Sarah, Tom and Fred

Parents

James Alfred Pope (1912 - 1992) started at Norbin Barton Farm, South Wraxall. in 1943 he moved to Kingsdown Farm later adding Lodge Farm and Closes Farm.

He married Kathleen Gladys Webb in 1935.

Children: Bryan (b 1935); Roger (b 1939); Michael George (b 1943)

Mike Pope married Carol George in 1970.

Children: George James; and Edward Keith.

Grandparents

Fredrick George Pope (1882 - 1954) of Manor Farm, Marden, Devizes married Mary Matilda Wells in 1911

Children: James Alfred, Una, Bryan, Gene, Sarah, Tom and Fred

Parents

James Alfred Pope (1912 - 1992) started at Norbin Barton Farm, South Wraxall. in 1943 he moved to Kingsdown Farm later adding Lodge Farm and Closes Farm.

He married Kathleen Gladys Webb in 1935.

Children: Bryan (b 1935); Roger (b 1939); Michael George (b 1943)

Mike Pope married Carol George in 1970.

Children: George James; and Edward Keith.