How to Charm a Pig:

Culture wars, folk medicine and veterinary care in mid-17th century Box

Jonathan Parkhouse November 2023

Culture wars, folk medicine and veterinary care in mid-17th century Box

Jonathan Parkhouse November 2023

Previous articles on this website have examined the career of Walter Bushnell (1608 – 1667), who was ordained a deacon in 1636 and appointed as curate at Box, assisting the then vicar John Coren and subsequently replacing him as vicar on the latter’s death in 1644.[1] This was not a good time to be a vicar; there was enmity between different religious factions and the civil war was fought for religious conviction as much as political ideology, indeed it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between the two. Catholics were still viewed with extreme suspicion and numerous radical sects flourished. Ministers of religion were constantly being scrutinised for deviation from the party line, and there were plenty of opportunities for extremists, or those with petty grudges, to make trouble. Bushnell was certainly unpopular with many in the parish; he was wealthy (the monetary bequests in his will alone total £274) and was friendly with the Spekes and the Longs, both families with recusant leanings. Moreover, the Box parishioners had form in vicar-baiting; John Coren had been accused of bad debts, papist practices and drunkenness.[2]

It may not be entirely surprising that some parishioners were keen to wage their own particular ‘culture wars’ when the opportunity arose.

In 1654, early during the Protectorate, Cromwell’s Council of State passed various ordinances in response to the collapse in ecclesiastical administration during the Republic (1649-53); these included the establishment at County level of Commissions of Electors to expel inadequate ministers and schoolmasters from their livings. Cromwell’s reforms endeavoured to put a stop to that heady way, touched of likewise this day, of every man making himself a minister and a preacher. It hath endeavoured to settle a way for the approbation of men of piety and ability for the discharge of that work. And I think I may say, it hath committed that work to the trust of persons, both of the Presbyterian and Independent judgments, men of as known ability, piety, and integrity, as I believe any this nation hath … they go upon such a character as the Scripture warrants to put men into that great employment; and to approve men for it, who are men who have received gifts from Him that ascended up on high.[3]

Between 1655 and 1658 Bushnell appeared nine times before the Committee of Ejectors for being an insufficient minister, profaning the Sabbath, baptising with the sign of the cross, drunkenness, playing cards and dice, criticising the Government in associating himself with severall persons who were chief Actors in the late Insurrection and attempting to induce his serving woman to acts of uncleanliness. Amongst the accusers were the Pinchins, the Cottles, and Obadiah Cheltenham of Ditteridge who claimed that Bushnell had repeated the same prayer before every sermon, that the very Boyes of the Street, could repeat it and laugh at it. Despite his protestations,[4] Bushnell was ejected from the living in 1655 in favour of John Stern but re-appointed in 1662 after the Restoration. In 1660 Bushnell, then living with his sister in Bath, wrote an account of his appearances before the Commission.[5] Bushnell’s account attempts, often at such inordinate length that a degree of special pleading may be suspected, to illustrate the bias of his accusers, many of whom had form in bringing false accusations against the clergy, and to show irregularities in the judicial process; the episode may tell us more about the febrile nature of churchmanship during the commonwealth, a period described by Bushnell as touchie, hazardous, suspicious,[6] as well as parochial petty vindictiveness, than about the man himself. Indeed, a further set of counter-accusations was published by one of the Commissioners’ assistants, Humphrey Chambers, Rector of Pewsey, in order to vindicate their actions; this exchange might have continued further had the Restoration not served to dampen down such disputes.[7]

One of the narrative techniques employed by Bushnell was to blacken the character of his detractors. Particular ire is reserved for William Pinchin; the Pinchins owed Bushnell money and he had refused them further credit, but one of the more interesting accusations was made against Nicholas Spencer of Ashley.

Spencer had lived in Ashley and had the status of Yeoman, according to his will dated 17 July 1662;[8] he was buried at Box church on 31 July 1662. He was related to the Pinchin family by marriage. Bushnell cast doubts on his respectability, claiming that he and William Pinchin were very bold with their Landlords wood and timber, felling when and where they had no such license.[9]

Bushnell goes on to recount that this Nicholas Spenser professeth a skill in the recovery of such who are distracted; and withall, that he doth sometime practise upon Pigs, being alike distempered; now I know not what courses he takes for the recovery of men; but I have been told that for Hogs he hath this Receit; That he cuts an Apple, or a piece of Cheese, and writes upon it Sare, Nare, Fare, and then by inversion Fare, Nare, Sare, and so gives it the Hog; for which (as I have been told) he hath received money, or something aequivalent. Now this must be either a Charm or a Cheat, both which are punishable by our Municipal Laws.[10]

Bushnell stops short of an outright accusation that Spencer was practising spells upon humans, although it is not hard to see an insinuation here. Nevertheless, irrespective of the truth of the matter, Bushnell’s account gives a snapshot of the popular folk remedies available in an age before antibiotics. The remedy described here has parallels with others, where ‘nonsense words’ were used in conjunction with objects, in this case cheese or an apple. There are numerous accounts of charmers or ‘cunning-men’ who dispensed traditional remedies, which ranged from common-sense remedies, inherited lore about the healing properties of plants and minerals, to practical experience. Alongside these were various practices which we may term ‘ritual’, which ranged from magic spells through to prayers, often half-remembered and mangled fragments of Latin prayers, or even Greek or Hebrew. The impenetrability of the formula would give it its power.[11] In 1601 in Cambridgeshire one Oliver Den was accused of sorcery by writing certain words on a piece of paper and feeding it to a mad dog, whilst Walter Ward having certain hogs who had been bitten with a mad dog, the said Den did take apples and cut them into halves and did take the half parts of these apples and wrote certain letters on them, and gave the same to the said hogs, by which he said he would keep the said hogs from running mad or … dying.[12] A similar example is provided by a manuscript volume of medical recipes and prescriptions which belonged to King Charles II’s physician, Sir John Floyer, which prescribed for madness in a dog or any other animal pega, tega, sega, docemena Mega. These words written, and ye paper rolled up and given to a Dog or anything that is mad, cure him.[13] The parallels with the remedy which Bushnell alleged was employed by Nicholas Spencer are obvious.

Charms of this sort were commonplace, but not universally approved of – much of what we know about them comes from evidence presented to the ecclesiastical courts. The practices existed at the intersection of science (as understood at the time, which included astrology), popular Christian piety, tradition, and witchcraft. Officially both catholic and protestant teaching forbade witchcraft, and the Church had been battling against popular magic as much before the Reformation as afterwards, but there were large grey areas. To a diehard puritan, many catholic practices were indistinguishable from witchcraft, and indeed old Latin prayers were popular for use in charms.[14] ‘Papist’ and ‘popery’ became terms of abuse, but to many laypersons such ‘magical’ healing was a continuation of the tradition of combining prayer with folk remedies, and a common defence against charges of sorcery was that the defendant was doing no more than helping people with their prayers. Alongside this was the belief that disease was something foreign to the body that needed to be drawn out. There was an element of secrecy about all this; often the cunning-man or cunning-woman would keep the patient in ignorance of the wording of the formulae employed, which were written down more often by those seeking to discredit the practice, or the individual practitioner, as diabolical or fraudulent. Such charm-books as survive are written manuscripts, rather than printed volumes. Yet such practices must have permeated society; writing words on an apple is after all not so very different from scratching apotropaic graffiti on to the church wall. Indeed, there are documented instances of churchwardens resorting to ‘cunning men’ to assist in the recovery of stolen church property.

Spencer’s will gives every impression of his respectability; the short religious preface follows a more or less standard formula and the bequests indicate a man of means who moved in similar social circles. Were it not for Walter Bushnell we would have no indication that his behaviour was in any way out of the ordinary, and indeed it may not have been. It is only after the foundation of bodies such as the Royal Society in 1660 that recourse to popular remedies, relying upon what we might now regard as irrationality, began to decrease, but it was a slow change over centuries.

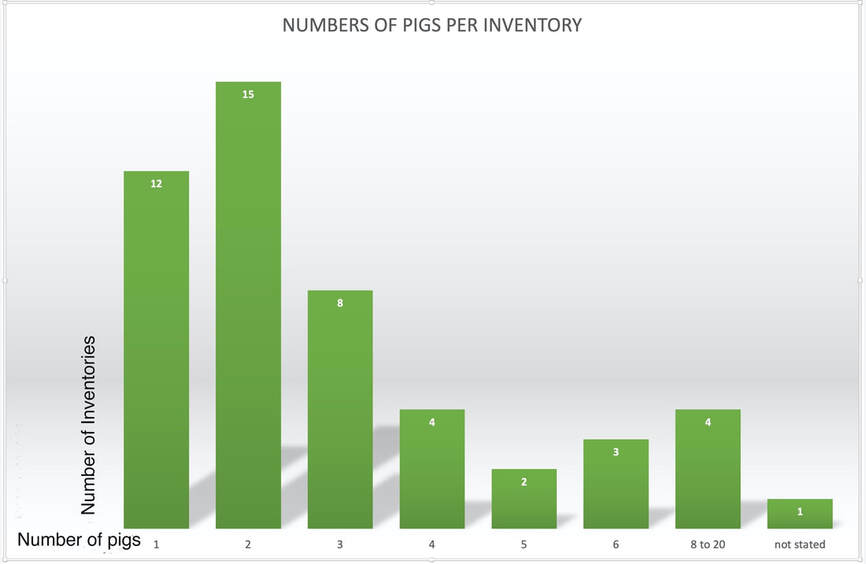

The welfare of pigs – and indeed other livestock – would have been important to the residents of Box. Over half the probate inventories for Box and Ditteridge between 1603 and 1715 list at least one pig. As the chart indicates, most of those who kept pigs only had between one to three animals. Only the wealthy yeoman Simon Collett (died 1695), with twenty pigs, seems to have been farming pigs on a commercial basis, along with a flock of 400 sheep and lambs, as well as 10 plough oxen, 16 milch cows, 1 bull, ten young beasts and 4 weaned calves.[15] Most people who kept pigs did so for domestic consumption, flitches of bacon being another common entry in the surviving probate inventories. For many households in Box the pig in the back yard was a significant element of the domestic economy and their health and wellbeing were important, but those pigs may have had to rely on charms written upon apples and cheese for their health long after the time of Bushnell and Spencer.

It may not be entirely surprising that some parishioners were keen to wage their own particular ‘culture wars’ when the opportunity arose.

In 1654, early during the Protectorate, Cromwell’s Council of State passed various ordinances in response to the collapse in ecclesiastical administration during the Republic (1649-53); these included the establishment at County level of Commissions of Electors to expel inadequate ministers and schoolmasters from their livings. Cromwell’s reforms endeavoured to put a stop to that heady way, touched of likewise this day, of every man making himself a minister and a preacher. It hath endeavoured to settle a way for the approbation of men of piety and ability for the discharge of that work. And I think I may say, it hath committed that work to the trust of persons, both of the Presbyterian and Independent judgments, men of as known ability, piety, and integrity, as I believe any this nation hath … they go upon such a character as the Scripture warrants to put men into that great employment; and to approve men for it, who are men who have received gifts from Him that ascended up on high.[3]

Between 1655 and 1658 Bushnell appeared nine times before the Committee of Ejectors for being an insufficient minister, profaning the Sabbath, baptising with the sign of the cross, drunkenness, playing cards and dice, criticising the Government in associating himself with severall persons who were chief Actors in the late Insurrection and attempting to induce his serving woman to acts of uncleanliness. Amongst the accusers were the Pinchins, the Cottles, and Obadiah Cheltenham of Ditteridge who claimed that Bushnell had repeated the same prayer before every sermon, that the very Boyes of the Street, could repeat it and laugh at it. Despite his protestations,[4] Bushnell was ejected from the living in 1655 in favour of John Stern but re-appointed in 1662 after the Restoration. In 1660 Bushnell, then living with his sister in Bath, wrote an account of his appearances before the Commission.[5] Bushnell’s account attempts, often at such inordinate length that a degree of special pleading may be suspected, to illustrate the bias of his accusers, many of whom had form in bringing false accusations against the clergy, and to show irregularities in the judicial process; the episode may tell us more about the febrile nature of churchmanship during the commonwealth, a period described by Bushnell as touchie, hazardous, suspicious,[6] as well as parochial petty vindictiveness, than about the man himself. Indeed, a further set of counter-accusations was published by one of the Commissioners’ assistants, Humphrey Chambers, Rector of Pewsey, in order to vindicate their actions; this exchange might have continued further had the Restoration not served to dampen down such disputes.[7]

One of the narrative techniques employed by Bushnell was to blacken the character of his detractors. Particular ire is reserved for William Pinchin; the Pinchins owed Bushnell money and he had refused them further credit, but one of the more interesting accusations was made against Nicholas Spencer of Ashley.

Spencer had lived in Ashley and had the status of Yeoman, according to his will dated 17 July 1662;[8] he was buried at Box church on 31 July 1662. He was related to the Pinchin family by marriage. Bushnell cast doubts on his respectability, claiming that he and William Pinchin were very bold with their Landlords wood and timber, felling when and where they had no such license.[9]

Bushnell goes on to recount that this Nicholas Spenser professeth a skill in the recovery of such who are distracted; and withall, that he doth sometime practise upon Pigs, being alike distempered; now I know not what courses he takes for the recovery of men; but I have been told that for Hogs he hath this Receit; That he cuts an Apple, or a piece of Cheese, and writes upon it Sare, Nare, Fare, and then by inversion Fare, Nare, Sare, and so gives it the Hog; for which (as I have been told) he hath received money, or something aequivalent. Now this must be either a Charm or a Cheat, both which are punishable by our Municipal Laws.[10]

Bushnell stops short of an outright accusation that Spencer was practising spells upon humans, although it is not hard to see an insinuation here. Nevertheless, irrespective of the truth of the matter, Bushnell’s account gives a snapshot of the popular folk remedies available in an age before antibiotics. The remedy described here has parallels with others, where ‘nonsense words’ were used in conjunction with objects, in this case cheese or an apple. There are numerous accounts of charmers or ‘cunning-men’ who dispensed traditional remedies, which ranged from common-sense remedies, inherited lore about the healing properties of plants and minerals, to practical experience. Alongside these were various practices which we may term ‘ritual’, which ranged from magic spells through to prayers, often half-remembered and mangled fragments of Latin prayers, or even Greek or Hebrew. The impenetrability of the formula would give it its power.[11] In 1601 in Cambridgeshire one Oliver Den was accused of sorcery by writing certain words on a piece of paper and feeding it to a mad dog, whilst Walter Ward having certain hogs who had been bitten with a mad dog, the said Den did take apples and cut them into halves and did take the half parts of these apples and wrote certain letters on them, and gave the same to the said hogs, by which he said he would keep the said hogs from running mad or … dying.[12] A similar example is provided by a manuscript volume of medical recipes and prescriptions which belonged to King Charles II’s physician, Sir John Floyer, which prescribed for madness in a dog or any other animal pega, tega, sega, docemena Mega. These words written, and ye paper rolled up and given to a Dog or anything that is mad, cure him.[13] The parallels with the remedy which Bushnell alleged was employed by Nicholas Spencer are obvious.

Charms of this sort were commonplace, but not universally approved of – much of what we know about them comes from evidence presented to the ecclesiastical courts. The practices existed at the intersection of science (as understood at the time, which included astrology), popular Christian piety, tradition, and witchcraft. Officially both catholic and protestant teaching forbade witchcraft, and the Church had been battling against popular magic as much before the Reformation as afterwards, but there were large grey areas. To a diehard puritan, many catholic practices were indistinguishable from witchcraft, and indeed old Latin prayers were popular for use in charms.[14] ‘Papist’ and ‘popery’ became terms of abuse, but to many laypersons such ‘magical’ healing was a continuation of the tradition of combining prayer with folk remedies, and a common defence against charges of sorcery was that the defendant was doing no more than helping people with their prayers. Alongside this was the belief that disease was something foreign to the body that needed to be drawn out. There was an element of secrecy about all this; often the cunning-man or cunning-woman would keep the patient in ignorance of the wording of the formulae employed, which were written down more often by those seeking to discredit the practice, or the individual practitioner, as diabolical or fraudulent. Such charm-books as survive are written manuscripts, rather than printed volumes. Yet such practices must have permeated society; writing words on an apple is after all not so very different from scratching apotropaic graffiti on to the church wall. Indeed, there are documented instances of churchwardens resorting to ‘cunning men’ to assist in the recovery of stolen church property.

Spencer’s will gives every impression of his respectability; the short religious preface follows a more or less standard formula and the bequests indicate a man of means who moved in similar social circles. Were it not for Walter Bushnell we would have no indication that his behaviour was in any way out of the ordinary, and indeed it may not have been. It is only after the foundation of bodies such as the Royal Society in 1660 that recourse to popular remedies, relying upon what we might now regard as irrationality, began to decrease, but it was a slow change over centuries.

The welfare of pigs – and indeed other livestock – would have been important to the residents of Box. Over half the probate inventories for Box and Ditteridge between 1603 and 1715 list at least one pig. As the chart indicates, most of those who kept pigs only had between one to three animals. Only the wealthy yeoman Simon Collett (died 1695), with twenty pigs, seems to have been farming pigs on a commercial basis, along with a flock of 400 sheep and lambs, as well as 10 plough oxen, 16 milch cows, 1 bull, ten young beasts and 4 weaned calves.[15] Most people who kept pigs did so for domestic consumption, flitches of bacon being another common entry in the surviving probate inventories. For many households in Box the pig in the back yard was a significant element of the domestic economy and their health and wellbeing were important, but those pigs may have had to rely on charms written upon apples and cheese for their health long after the time of Bushnell and Spencer.

References

[1] D Ibberson 2015 Walter Bushnell, vicar of Box 1644-1655 and 1660-1666: The Rise, Fall and Rise Again http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/walter-bushnell.html

[2] CE McGee (2023) Box, Wiltshire, 1606-1610 Coren vs. Seede Records of Early English Drama Pre-publication Collections (web) https://reedprepub.org/box-wiltshire/ (accessed 24.02.2023); M.Ingram 1987, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England, 1570-1640. Cambridge University Press, 110-11

[3] W.C. Abbott (ed.), 1937-47 The Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell, 4 vols. (Cambridge, MA, and London), vol. 3, p. 440.

[4] W. Bushnell 1660 A narrative of the proceedings of the commissioners appointed by O. Cromwell, for ejecting scandalous and ignorant ministers, in the case of Walter Bushnell, clerk, Vicar of Box in the county of Wilts wherein is shewed that both commissioners, ministers, clerk, witnesses have acted as unjustly even as was possible for men to do by such a power, and all under the pretence of godliness and reformation. London https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A30710.0001.001/1:17?rgn=div1;view=fulltext (accessed 18.02.2023)

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid. 214

[7] H Chambers 1660 An answer of Humphrey Chambers, D. D. rector of Pewsey, in the county of Wilts, to the charge of Walter Bvshnel, vicar of Box, in the same county published in a book of his entituled, A narrative of the proceedings of the commissioners appointed by O. Cromwel for ejecting scandalous and ignorant ministers, in the case of Walter Bushnel, &c. : with a vindication of the said commissioners annexed : humbly submitted to publick censure. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A31649.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext (accessed 19.02.2023)

[8] TNA PROB 11/309/225

[9] Bushnell 1660, 129

[10] Ibid p.198.

[11] Thomas K 1973, Religion and the Decline of Magic (2nd edition) London, Penguin, p.214. Thomas provides numerous examples of how such charms or spells were used in conjunction with prayer and herbal medicine. esp. pp 210-217.

[12] ibid. p.216

[13] J. Hewitt, 1872 ‘Medical recipes of the seventeenth century’ Archaeological Journal 29, pp71-77

[14] Thomas 1973, p. 325

[15] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre: P3/C/583

[1] D Ibberson 2015 Walter Bushnell, vicar of Box 1644-1655 and 1660-1666: The Rise, Fall and Rise Again http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/walter-bushnell.html

[2] CE McGee (2023) Box, Wiltshire, 1606-1610 Coren vs. Seede Records of Early English Drama Pre-publication Collections (web) https://reedprepub.org/box-wiltshire/ (accessed 24.02.2023); M.Ingram 1987, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England, 1570-1640. Cambridge University Press, 110-11

[3] W.C. Abbott (ed.), 1937-47 The Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell, 4 vols. (Cambridge, MA, and London), vol. 3, p. 440.

[4] W. Bushnell 1660 A narrative of the proceedings of the commissioners appointed by O. Cromwell, for ejecting scandalous and ignorant ministers, in the case of Walter Bushnell, clerk, Vicar of Box in the county of Wilts wherein is shewed that both commissioners, ministers, clerk, witnesses have acted as unjustly even as was possible for men to do by such a power, and all under the pretence of godliness and reformation. London https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A30710.0001.001/1:17?rgn=div1;view=fulltext (accessed 18.02.2023)

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid. 214

[7] H Chambers 1660 An answer of Humphrey Chambers, D. D. rector of Pewsey, in the county of Wilts, to the charge of Walter Bvshnel, vicar of Box, in the same county published in a book of his entituled, A narrative of the proceedings of the commissioners appointed by O. Cromwel for ejecting scandalous and ignorant ministers, in the case of Walter Bushnel, &c. : with a vindication of the said commissioners annexed : humbly submitted to publick censure. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A31649.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext (accessed 19.02.2023)

[8] TNA PROB 11/309/225

[9] Bushnell 1660, 129

[10] Ibid p.198.

[11] Thomas K 1973, Religion and the Decline of Magic (2nd edition) London, Penguin, p.214. Thomas provides numerous examples of how such charms or spells were used in conjunction with prayer and herbal medicine. esp. pp 210-217.

[12] ibid. p.216

[13] J. Hewitt, 1872 ‘Medical recipes of the seventeenth century’ Archaeological Journal 29, pp71-77

[14] Thomas 1973, p. 325

[15] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre: P3/C/583