|

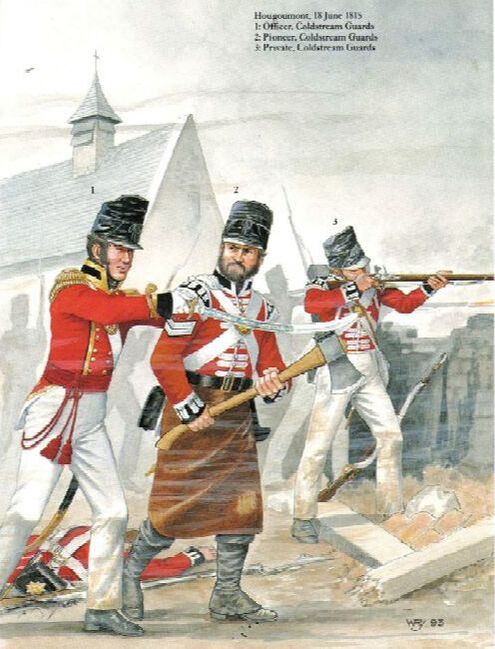

Obadiah Smith, 1790-1855 Jane Browning February 2021 The Story of one Wiltshire man, Obadiah Smith, who was injured at the Battle of Waterloo and the effect the Napoleonic Wars had on the people of Box. Obadiah Smith was baptised in Box church on 18th April 1790 to Robert Smith and his wife Anna (sometimes Anne or Hannah) née Hodge. He married Hannah Jones, from Corsham, some 3 miles away, on 10th June 1810 at Box and died on 9th March 1855 aged 64 and was buried, again in Box, on the 13th. These basic facts belie his story. He did not spend his entire life in Box but served his country in The Netherlands and France and in one of our most famous battles. Left: Coldstream Guards at Waterloo (Pinterest) |

It was the 1851 census which alerted me to something a little different for Obadiah as he identified himself as a Chelsea pensioner; so my research expanded. When one mentions Chelsea Pensioners we automatically think of those Chelsea Pensioners living in the Royal Hospital at Chelsea which was founded in 1682 by King Charles II as a hostel for former Army soldiers. By the time the hospital was built there were more eligible soldiers than places available and so those able to live away from the hospital were given a pension and became Out-Pensioners. By 1815 there were 36,757 Out-Pensioners.

So what do we know about Obadiah’s service in the Army? He enrolled, for 18 years, as a Private in His Majesty’s Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards commanded by the Rt. Hon. The Duke of Cambridge on 5 April 1813 at Chippenham, giving his occupation as a mason and his age as 21. (He was, in fact, just short of 23 years of age, based on his baptism date.)

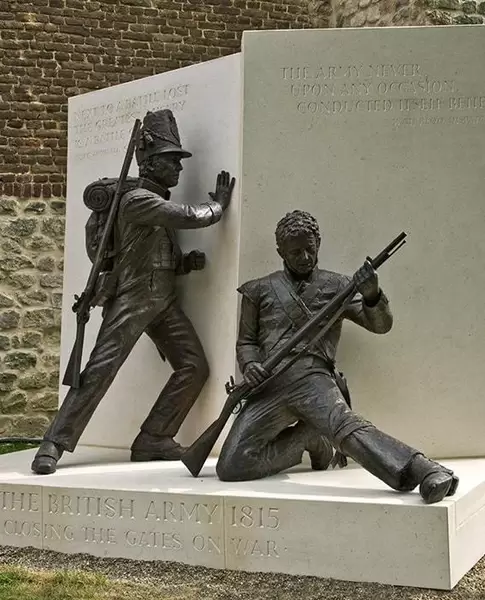

Just two years into his service, in 1815, the Coldstreams served as part of the 2nd Guards Brigade in the château of Hougoumont on the outskirts of Waterloo, resisting the French attack. This defence is considered one of the greatest achievements of the regiment. The Duke of Wellington himself declared after the battle that the success of the battle turned upon closing the gates at Hougoumont. One third of the British regulars were killed or wounded in the battle, some 15,000.

So what do we know about Obadiah’s service in the Army? He enrolled, for 18 years, as a Private in His Majesty’s Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards commanded by the Rt. Hon. The Duke of Cambridge on 5 April 1813 at Chippenham, giving his occupation as a mason and his age as 21. (He was, in fact, just short of 23 years of age, based on his baptism date.)

Just two years into his service, in 1815, the Coldstreams served as part of the 2nd Guards Brigade in the château of Hougoumont on the outskirts of Waterloo, resisting the French attack. This defence is considered one of the greatest achievements of the regiment. The Duke of Wellington himself declared after the battle that the success of the battle turned upon closing the gates at Hougoumont. One third of the British regulars were killed or wounded in the battle, some 15,000.

A Muster Book shows he served in Lieutenant Colonel Sir R Arbuthnot’s Company. This muster book was for the 182 days from the 25th December 1814 to 24th June 1815. An Officers Certificate has been annotated with a “W” for those who had served at the Battle of Waterloo.[1] His service record shows Obadiah was wounded in his right hand at the battle, losing the first joint of his right thumb and that his conduct has been that of a good and efficient soldier seldom in Hospital, Trustworthy and sober.[2]

Another document lists those men present on the 16th , 17th and 18th June 1815, the period of the battle of Waterloo.[3] This enabled Obadiah to be given the additional 2 years service which was awarded to all those men who were present at the Battle of Waterloo. This would have enhanced his final pension.

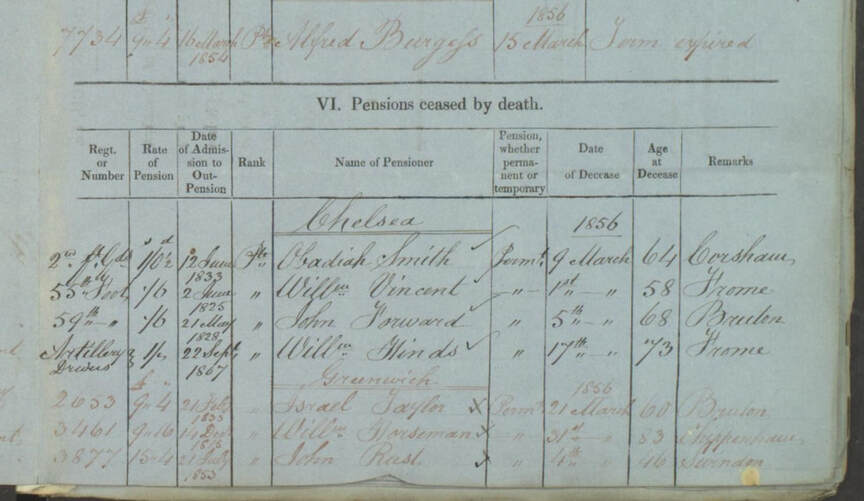

The last document I could find shows he became on Out-Pensioner on 12 June 1833, being awarded a permanent pension of 1 shilling and a halfpenny per day. After 20 years and 69 days in the Army, Obadiah returned to Box and life with his family.[4]

In 1841 Obadiah was living at Woodstock, in Mill Lane, Box giving his occupation as a miner, (probably in the stone quarries at Box, though these men were usually called quarry workers) with his wife Hannah and sons John and David, neither of whom was born in Wiltshire. In 1851 he, Hannah and David had moved within the village to Pye Corner, giving his occupation as a Chelsea Pensioner. He died on the 9th March 1856, aged 66.

Another document lists those men present on the 16th , 17th and 18th June 1815, the period of the battle of Waterloo.[3] This enabled Obadiah to be given the additional 2 years service which was awarded to all those men who were present at the Battle of Waterloo. This would have enhanced his final pension.

The last document I could find shows he became on Out-Pensioner on 12 June 1833, being awarded a permanent pension of 1 shilling and a halfpenny per day. After 20 years and 69 days in the Army, Obadiah returned to Box and life with his family.[4]

In 1841 Obadiah was living at Woodstock, in Mill Lane, Box giving his occupation as a miner, (probably in the stone quarries at Box, though these men were usually called quarry workers) with his wife Hannah and sons John and David, neither of whom was born in Wiltshire. In 1851 he, Hannah and David had moved within the village to Pye Corner, giving his occupation as a Chelsea Pensioner. He died on the 9th March 1856, aged 66.

Box Napoleonic Servicemen

I wonder how many other Box residents had served at the Battle of Waterloo? In the early 19th century the people of England were very concerned about a possible invasion of England by the French. The 18th century had seen a constant series of wars across Europe which had involved virtually every European state at one time or another during the course of the wars. England, alone of those countries which had taken up arms against France over the decades, had managed to avoid defeat. Napoleon had made no secret of his intentions to invade England, in 1803 amassing a huge army on the shores at Calais to show his intentions.

The government responded by strengthening existing defences and building new ones along the south coast, notably the Martello towers which can still be seen today. These reinforcements came at no small cost, and taxes were again increased to fund the war effort. Many British men and women were left in desperate misery due to high taxes, skyrocketing food prices, unemployment caused by wartime trade restrictions, and the increased use of labour-saving machinery. Economic struggles forced many men to sign up for the army.

The situation was considered to be so bad in England that in 1803 preparations were made to identify all those men who could be called upon to form a volunteer force in case of an invasion by the French. Documents provide an insight into the preparations made. In Box a list of men, in alphabetical order, was made on 26th July 1803 by Mr Horlock listing the local men and giving their occupations, age, how many children they had, any impediments and whether they would be prepared to volunteer. The first man was Joseph Adams, a mason, with no children, who said he would volunteer; Zeph Bullock, clockmaker, George Vezey labourer and John Hobbs, a labourer, were similarly placed; Francis Hobbs was aged between 17 and 30, had 2 children, and agreed to volunteer; butcher James Vezey was also between 17 and 30 and also had 2 children – he proposed to go into the cavalry.

A statistical return of livestock was also made and three millers were named (Geo. Young, Mr Pinchin and Edw. Balder) who were to make 36 bags of flour, although a note says they will not provide the wheat nor carry the flour from their mills.

The volunteers were to be given 20 shillings each every 3 years for clothing, and 1 shilling a day for 20 days exercising a year.

Mr James Cottle was to be captain of the Pioneers and Isaac Kingston was one of six to be appointed superintendents.

It was during this period that the public in general supported the military. These were the days reflected in Jane Austen’s novels, particularly Pride and Prejudice, in which military men in their dashing uniforms were enthusiastically welcomed into local towns and villages to relieve the monotony of general life.

The seriousness of the situation meant that 1803 was also the year income tax was re-introduced. It had been introduced for the first time in 1799 as a temporary measure to fund the war against France but had been abolished after a short period of peace. It was abolished yet again after Waterloo but was re-introduced in 1842 due to a shortage of government funds. It has never been a permanent tax and has to be voted for annually by Parliament. The crushing of Napoleon at Waterloo heralded a period of peace in England.

I wonder how many other Box residents had served at the Battle of Waterloo? In the early 19th century the people of England were very concerned about a possible invasion of England by the French. The 18th century had seen a constant series of wars across Europe which had involved virtually every European state at one time or another during the course of the wars. England, alone of those countries which had taken up arms against France over the decades, had managed to avoid defeat. Napoleon had made no secret of his intentions to invade England, in 1803 amassing a huge army on the shores at Calais to show his intentions.

The government responded by strengthening existing defences and building new ones along the south coast, notably the Martello towers which can still be seen today. These reinforcements came at no small cost, and taxes were again increased to fund the war effort. Many British men and women were left in desperate misery due to high taxes, skyrocketing food prices, unemployment caused by wartime trade restrictions, and the increased use of labour-saving machinery. Economic struggles forced many men to sign up for the army.

The situation was considered to be so bad in England that in 1803 preparations were made to identify all those men who could be called upon to form a volunteer force in case of an invasion by the French. Documents provide an insight into the preparations made. In Box a list of men, in alphabetical order, was made on 26th July 1803 by Mr Horlock listing the local men and giving their occupations, age, how many children they had, any impediments and whether they would be prepared to volunteer. The first man was Joseph Adams, a mason, with no children, who said he would volunteer; Zeph Bullock, clockmaker, George Vezey labourer and John Hobbs, a labourer, were similarly placed; Francis Hobbs was aged between 17 and 30, had 2 children, and agreed to volunteer; butcher James Vezey was also between 17 and 30 and also had 2 children – he proposed to go into the cavalry.

A statistical return of livestock was also made and three millers were named (Geo. Young, Mr Pinchin and Edw. Balder) who were to make 36 bags of flour, although a note says they will not provide the wheat nor carry the flour from their mills.

The volunteers were to be given 20 shillings each every 3 years for clothing, and 1 shilling a day for 20 days exercising a year.

Mr James Cottle was to be captain of the Pioneers and Isaac Kingston was one of six to be appointed superintendents.

It was during this period that the public in general supported the military. These were the days reflected in Jane Austen’s novels, particularly Pride and Prejudice, in which military men in their dashing uniforms were enthusiastically welcomed into local towns and villages to relieve the monotony of general life.

The seriousness of the situation meant that 1803 was also the year income tax was re-introduced. It had been introduced for the first time in 1799 as a temporary measure to fund the war against France but had been abolished after a short period of peace. It was abolished yet again after Waterloo but was re-introduced in 1842 due to a shortage of government funds. It has never been a permanent tax and has to be voted for annually by Parliament. The crushing of Napoleon at Waterloo heralded a period of peace in England.

References

[1]The National Archives WO 100/14

[2]The National Archives WO 97/209/76

[3]The National Archives WO 100/14

[4]The National Archives WO 22/3/53

[1]The National Archives WO 100/14

[2]The National Archives WO 97/209/76

[3]The National Archives WO 100/14

[4]The National Archives WO 22/3/53