New Technologies Alan Payne September 2022

We sometimes take for granted many of the improvements to life since the Second World War: things like washing machines, dishwashers, private motor cars, overdrafts and mortgages. But we should not forget that, until the 1950s, many Box houses were without internal plumbing, domestic hot water and electricity. Earlier still, our world would have been incomprehensible to villagers of the 1930s with television, electric toothbrushes, central heating and the leisure generated by time-saving appliances. And I haven’t mentioned the internet, information technology and life expectations with massively improved health care. Yet it was the technological improvements of the inter-war period that sowed the seeds for much of our world.

Changing Economic Conditions

It is sometimes claimed that in the high Victorian period Britain was the workshop of the world, manufacturing and selling goods throughout the Empire and the world. But more accurately expressed it was the world-leading trader, importing materials and re-exporting them as finished consumer goods.[1] And even then, a larger return was derived from overseas investments and services such as banking, insurance and shipping centred on the City of London.[2] The government was able to claim All out Trade Records Broken – Total Increase £107 million in 1912, even if Germany and USA were offering a world of fierce competition.[3] The war interrupted world trade and encouraged more local industrial growth and, at the same time, Britain was heavily indebted to USA for wartime necessities. Invisible earnings slumped.

It is sometimes claimed that in the high Victorian period Britain was the workshop of the world, manufacturing and selling goods throughout the Empire and the world. But more accurately expressed it was the world-leading trader, importing materials and re-exporting them as finished consumer goods.[1] And even then, a larger return was derived from overseas investments and services such as banking, insurance and shipping centred on the City of London.[2] The government was able to claim All out Trade Records Broken – Total Increase £107 million in 1912, even if Germany and USA were offering a world of fierce competition.[3] The war interrupted world trade and encouraged more local industrial growth and, at the same time, Britain was heavily indebted to USA for wartime necessities. Invisible earnings slumped.

|

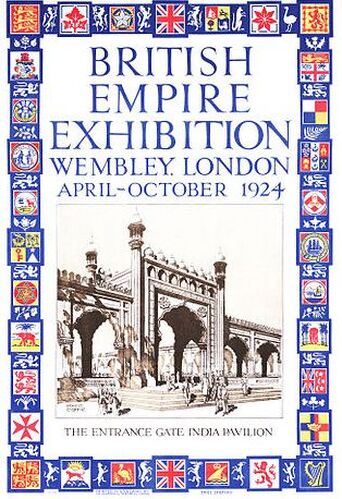

To help promote industry and trade in 1924-25, the government organised an exhibition at the newly-built Empire Stadium, Wembley (later renamed Wembley Stadium), emphasising the bonds that the Mother Country had with its Sister States and Daughters (the colonies).[4] Palaces of Engineering and Industry (exhibition buildings) were made of reinforced concrete in the style of imperial structures, such as a Burmese temple entered via a hand-crafted wooden bridge, Hong Kong’s Chinese Street and Palestine’s Jaffa oranges shown for the first time. Refrigeration, then in its infancy, brought meat and fresh produce from Canada and Australia, including a life-size butter sculpture from Australia of a cricket match with English batsman Jack Hobbs being stumped out by the Australians as they romped to a 4-1 series win.

The sculpture was kept cool behind a refrigerated glass enclosure. The king opened the event sending a telegram which travelled around the world in one minute twenty seconds until the repy was delivered to him by a telegram boy. It was also the first royal radio broadcast relayed by the British Broadcasting Corporation, formed two years earlier. Twenty-seven million visitors came to see displays from 56 countries of the Empire and in May 1926 the Box Schools held their own Wembley Exhibition displaying specimens including pieces of the Roman Villa pavement exhibited by John Hardy.[5] |

Scientific Discoveries

There were some significant scientific break-throughs in the inter-war years: insulin to treat diabetes was discovered in 1922, penicillin (the first antibiotic) in 1928 and vaccines against diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus in the 1930s. In domestic terms, pop-up toasters were invented in 1919 and frozen foods by Clarence Birdseye at the end of the First World War. In cosmopolitan towns and cities, the desk phone began to replace the old candlestick telephone after 1932, ballpoint pens after 1935 and photocopiers after 1938.

Quantum physics and our understanding of the sub-atomic world developed through the work of Max Born and Erwin Schrödinger. The relationship between the negatively-charged electron and the positively-charged nucleus and the effect of the vibration of atoms helped in the research to devise the hydrogen bomb. Wave theory assisted in the creation of lasers, transistors and semiconductors after the Second World War.

Box experienced these changes gradually with the decline of the old quarry trade industry and the emergence of new businesses with Perspex to make Spitfire windows at the Clift Quarry Works, Box Hill and vulcanised rubber tyres by Box Rubber Mills at the old Candle Factory, Quarry Hill. These industries eventually petered out (although Derek Price subsequently made tennis balls at the Candle Factory) but national advances in radio, electricity and the motor car quickly became part of everyday village life.

There were some significant scientific break-throughs in the inter-war years: insulin to treat diabetes was discovered in 1922, penicillin (the first antibiotic) in 1928 and vaccines against diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus in the 1930s. In domestic terms, pop-up toasters were invented in 1919 and frozen foods by Clarence Birdseye at the end of the First World War. In cosmopolitan towns and cities, the desk phone began to replace the old candlestick telephone after 1932, ballpoint pens after 1935 and photocopiers after 1938.

Quantum physics and our understanding of the sub-atomic world developed through the work of Max Born and Erwin Schrödinger. The relationship between the negatively-charged electron and the positively-charged nucleus and the effect of the vibration of atoms helped in the research to devise the hydrogen bomb. Wave theory assisted in the creation of lasers, transistors and semiconductors after the Second World War.

Box experienced these changes gradually with the decline of the old quarry trade industry and the emergence of new businesses with Perspex to make Spitfire windows at the Clift Quarry Works, Box Hill and vulcanised rubber tyres by Box Rubber Mills at the old Candle Factory, Quarry Hill. These industries eventually petered out (although Derek Price subsequently made tennis balls at the Candle Factory) but national advances in radio, electricity and the motor car quickly became part of everyday village life.

|

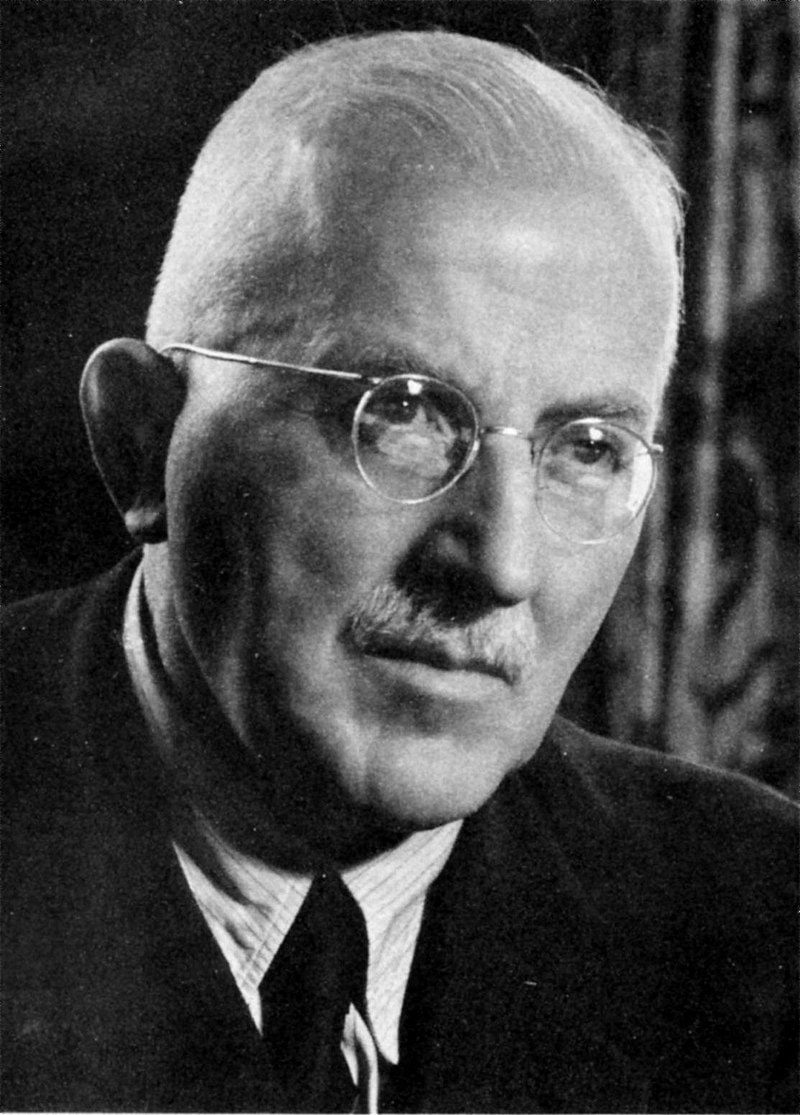

Arguably, these achievements were overshadowed by the German academic Hermann Staudinger in the field of chemistry. Virtually single-handedly, his theories revealed that polymers were made up of long chains of units bonded together. It was revolutionary work and enabled the formation of plastic, nylon, polythene, polystyrene, polyvinyl and polyester. These materials have shaped the world after the Second World War and still dominate our everyday lives with PVC clothing, car bumpers, plastic bottles, shampoo, rubber gloves and kitchen bowls. Hermann’s theories were taken up by British scientists and engineers to create huge conglomerate companies like ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) and GEC (the General Electric Company), which became two of the largest employers in British history. Despite the problems which plastics have caused and the negative effect on our environment, these innovations have revolutionised our societies. Left: Hermann Straudinger (courtesy Wiki) |

|

Wireless Broadcasts

Box strangely found itself a leader in West of England innovation in the inter-war period when Box Church achieved regional fame for broadcasting its Harvest Festival Service in 1933.[6] The West Regional Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation had only opened in May 1933 and Box was chosen as a typical West Country (church) service to be broadcast to an audience of about four million people, a really staggering thought. In actual fact using medium wave, the programme could be picked up widely across the UK and people wrote to vicar George Foster from Redland in north Bristol (Rev Foster’s previous parish), Pontypool, Abergavenny and Norfolk. Scores of letters were received in praise of the service – the dear bells, hearty congratulations to choir and organist, we have had the wireless since 1928, and never enjoyed anything so much before, it is wonderful this means of grace by wireless. Listeners from King’s Lynn, Norfolk, spoke of minor interruption from a foreign jazz band after which we could hear every syllable of Captain Stewart’s reading of the lesson. The Rawlings family, relatives of Box resident Stella Clarke also enjoyed the benefit of the wireless. The photo right shows Father Tom (seated) and his son outside the Hare and Hounds, Pickwick (photo courtesy Stella Clarke). |

Updating Facilities in Box

In terms of public facilities, the village of Box had lagged behind nearby towns. In 1925 a meeting of ratepayers was organised to bemoan that the implementation of the Watching and Lighting Act originally passed in 1833 was still lacking in Box.[7]

Only sporadic coal gas lamps had been installed, requiring a man to light and extinguish each lamp daily. The Central Electricity Board was only set up in 1926 to replace small, inefficient power stations and build a national grid, moving power around the country where it was needed.

In terms of public facilities, the village of Box had lagged behind nearby towns. In 1925 a meeting of ratepayers was organised to bemoan that the implementation of the Watching and Lighting Act originally passed in 1833 was still lacking in Box.[7]

Only sporadic coal gas lamps had been installed, requiring a man to light and extinguish each lamp daily. The Central Electricity Board was only set up in 1926 to replace small, inefficient power stations and build a national grid, moving power around the country where it was needed.

Recession dogged every thought in the inter-war period, however, and on Sunday 10 May 1935, Rev George Foster, the outgoing vicar, declared rather dramatically that on that date we were bankrupt, with a considerable sum owing for the electric light installation and with not enough money to pay for gas, coal and wages.[8] The church urgently needed £100 to survive.

The deficit was eventually funded by individuals in a most unusual way by funding and dedicating individual electric light bulb fittings at a cost of 30 shillings each. By March 1936, the vicar could declare that all 24 bulbs had been subscribed, the last being the vestry light.[9]

Motor Vehicles

Petrol-driven cars were in competition on Box roads with coal-powered traction engines. Crashes were comparatively common and even small incidents made news for the local papers. On 9 January 1925 a crash occurred on Box Hill at 8.50pm between a Sentinel steam wagon going about three miles per hour and a Morris Oxford 4-seater car driven by John Pitman of Bath.[10]

It was deemed to be an accident: Both drivers were taken unawares without realising the presence of another vehicle on the road. No one was injured and both vehicles later proceeded.

Cars became increasingly common in the 1920s, encouraging the invention of 3-colour traffic lights in 1920. A census was taken in Box on the Chippenham Road (presumably the High Street) which recorded an average over 16 hours of 3½ vehicles per minute in 1922 and 10 per minute in 1928.[11] What would it be now?

Moon Aircraft Products

Moon Aircraft Limited was formed as a company on 27 June 1941 as a subsidiary of the Bath and Portland Stone Firms Limited as they sought to diversify away from the stone quarry trade. It used part of the Firm’s headquarters at Clift Quarry Works,

Box Hill, and specialised in shaping Perspex (a polymer based on acrylic acid compounds) into the windows of war planes.

The company used their skilled design and masonry workforce to make precision drawings as the blueprint for Perspex cockpits because the material can be bent, cut and drilled. The technology and the development of the work at Clift probably predated the Second World War when it was commissioned to take on government contracts.

After the war, the company promoted itself as the Industry of the Future, manufacturing shades for electric lights, soap-trays, radio housing, fruit bowls and the items seen in the headline photograph but it was never large enough to be commercially viable.[12] It was sold at some point to Suntex Safety Glass Industries Limited and dissolved in 2009, having been dormant for some years. Industry in Box rather petered out with Moon Aircraft products.

The deficit was eventually funded by individuals in a most unusual way by funding and dedicating individual electric light bulb fittings at a cost of 30 shillings each. By March 1936, the vicar could declare that all 24 bulbs had been subscribed, the last being the vestry light.[9]

Motor Vehicles

Petrol-driven cars were in competition on Box roads with coal-powered traction engines. Crashes were comparatively common and even small incidents made news for the local papers. On 9 January 1925 a crash occurred on Box Hill at 8.50pm between a Sentinel steam wagon going about three miles per hour and a Morris Oxford 4-seater car driven by John Pitman of Bath.[10]

It was deemed to be an accident: Both drivers were taken unawares without realising the presence of another vehicle on the road. No one was injured and both vehicles later proceeded.

Cars became increasingly common in the 1920s, encouraging the invention of 3-colour traffic lights in 1920. A census was taken in Box on the Chippenham Road (presumably the High Street) which recorded an average over 16 hours of 3½ vehicles per minute in 1922 and 10 per minute in 1928.[11] What would it be now?

Moon Aircraft Products

Moon Aircraft Limited was formed as a company on 27 June 1941 as a subsidiary of the Bath and Portland Stone Firms Limited as they sought to diversify away from the stone quarry trade. It used part of the Firm’s headquarters at Clift Quarry Works,

Box Hill, and specialised in shaping Perspex (a polymer based on acrylic acid compounds) into the windows of war planes.

The company used their skilled design and masonry workforce to make precision drawings as the blueprint for Perspex cockpits because the material can be bent, cut and drilled. The technology and the development of the work at Clift probably predated the Second World War when it was commissioned to take on government contracts.

After the war, the company promoted itself as the Industry of the Future, manufacturing shades for electric lights, soap-trays, radio housing, fruit bowls and the items seen in the headline photograph but it was never large enough to be commercially viable.[12] It was sold at some point to Suntex Safety Glass Industries Limited and dissolved in 2009, having been dormant for some years. Industry in Box rather petered out with Moon Aircraft products.

References

[1] EJ Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire, 1969, Penguin Books, p.134-35

[2] EJ Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire,1969, Penguin Books, p.145

[3] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 11 January 1913

[4] Philip Grant, The British Empire Exhibition.pdf (brent.gov.uk)

[5] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[6] Parish Magazine, October and November 1933

[7] Courtesy Margaret Wakefield, Bath & Wilts Chronicle, 7 January 1925

[8] Parish Magazine, May 1935

[9] Parish Magazine, October 1935

[10] Courtesy Margaret Wakefield, Bath & Wilts Chronicle, 7 January 1925

[11] Parish Magazine, November 1933

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 December 1945

[1] EJ Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire, 1969, Penguin Books, p.134-35

[2] EJ Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire,1969, Penguin Books, p.145

[3] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 11 January 1913

[4] Philip Grant, The British Empire Exhibition.pdf (brent.gov.uk)

[5] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[6] Parish Magazine, October and November 1933

[7] Courtesy Margaret Wakefield, Bath & Wilts Chronicle, 7 January 1925

[8] Parish Magazine, May 1935

[9] Parish Magazine, October 1935

[10] Courtesy Margaret Wakefield, Bath & Wilts Chronicle, 7 January 1925

[11] Parish Magazine, November 1933

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 22 December 1945