|

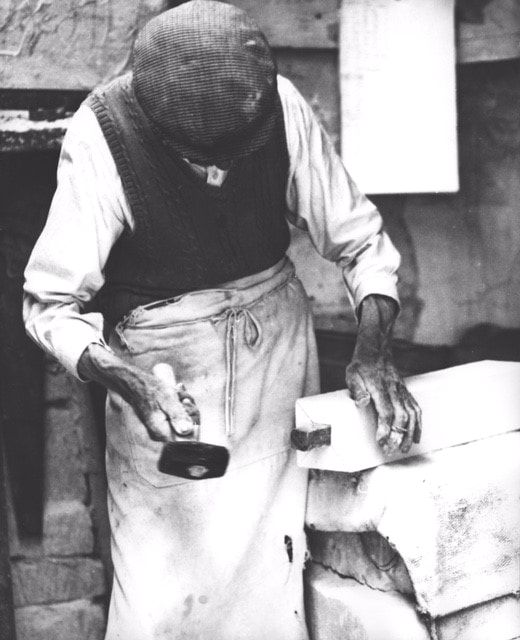

Box Tunnel to the Severn Tunnel: The Domestication of the Navvy Jill Maclean November 2019 Box residents will be familiar with the life and times of the railway navvy during the construction of Brunel’s great tunnel. What may not be so well known is that, as the 19th century progressed, amongst the lowly, lawless, hard-drinking navvies with their fearsome reputation, a highly skilled and experienced workforce emerged, trusted by contractors and engineers. They worked from contract to contract as required by their employer, taking families and possessions with them, living and participating in the local community. They rented property, provided lodgings for navvies of similar trades, and their children attended local schools and religious establishments. Right: The Black Gang, navvy bitumen coaters on the Manchester Ship Canal, 1880 (unknown attribution) |

Roots of the Navvies

So, where did this workforce come from? Evidence suggests that they came from every region, excavators or miners from Cornwall and Wales, banksmen from East Anglia, canal navvies from the North. Research undertaken by Dr David Brooke found that far from being itinerant Irish, most of the inexperienced workforce were local agricultural labourers who returned to their roots at harvest time, leaving their railway employers short of labour during periods of fair weather.[1] However, out of this workforce emerged the career navvy, those who built up their strength and expertise to take advantage of the high wages offered for dangerous work. By 1840, with the accident rate soaring, Parliament requested the many railway companies to provide information on the death and injury rate of workers. Only a few of the companies responded, including the Great Western, and so Parliament turned their attention to accidents amongst passengers and company servants, leaving the navvy workers forgotten.

Edwin Chadwick's Intervention

Yet, by 1846, the navvies and the conditions in which they worked, came under the scrutiny of Edwin Chadwick. Renowned for his reform of the dreaded Poor Law and the Workhouses, Chadwick had been made aware of conditions at the notorious Summit Tunnel at Woodhead on the Sheffield to Manchester railway, where living and working conditions were particularly poor, and where drunk and dissolute behaviour amongst the navvies led to disease, violence and death. Chadwick vented criticism on the railway company directors and contractors who, in his view, had relinquished responsibility for the unprotected, and often vulnerable workers and followers, and whose management favoured profit for the few. He demanded a system of government inspections and employer’s liability for death and injury, the forerunner of the later protective legislation. Chadwick had witnessed the destruction of working-class housing to make way for the railway, and feared that the promise of high wages would lure men to abandon their families who would be left to claim Parish Relief, or worse, on completion of works, would return home penniless and join the ranks of the able-bodied vagrant army so feared by middle-class Victorians, known as the Other.[2]

Pressure from Chadwick led to a Parliamentary Select Committee which called 32 witnesses, though few navvies. During the proceedings, admiration for two individual railway contractors was expressed, this formidable pair were Thomas Brassey and Samuel Morton Peto. One celebrated witness was Brunel, who spoke against the truck system and legislative interference, demanding reform from within the companies themselves. Despite the committee agreeing with Chadwick’s proposals, the matter was never brought before Parliament and again was quietly forgotten. Nevertheless, whilst Brunel and his team were constructing the Great Western Line, the two highly-successful contractors, Brassy and Peto, had emerged, understanding and respecting their navvy workforce. Praised by the Select Committee and by various Victorian primary sources both Thomas Brassey and Sir Samuel Morton Peto valued their experienced navvies, and their regard for their men bears testament to this. Non-conformist in belief, faith drove their behaviour and attitudes and was reflected in the loyalty they received in return.[3]

So, where did this workforce come from? Evidence suggests that they came from every region, excavators or miners from Cornwall and Wales, banksmen from East Anglia, canal navvies from the North. Research undertaken by Dr David Brooke found that far from being itinerant Irish, most of the inexperienced workforce were local agricultural labourers who returned to their roots at harvest time, leaving their railway employers short of labour during periods of fair weather.[1] However, out of this workforce emerged the career navvy, those who built up their strength and expertise to take advantage of the high wages offered for dangerous work. By 1840, with the accident rate soaring, Parliament requested the many railway companies to provide information on the death and injury rate of workers. Only a few of the companies responded, including the Great Western, and so Parliament turned their attention to accidents amongst passengers and company servants, leaving the navvy workers forgotten.

Edwin Chadwick's Intervention

Yet, by 1846, the navvies and the conditions in which they worked, came under the scrutiny of Edwin Chadwick. Renowned for his reform of the dreaded Poor Law and the Workhouses, Chadwick had been made aware of conditions at the notorious Summit Tunnel at Woodhead on the Sheffield to Manchester railway, where living and working conditions were particularly poor, and where drunk and dissolute behaviour amongst the navvies led to disease, violence and death. Chadwick vented criticism on the railway company directors and contractors who, in his view, had relinquished responsibility for the unprotected, and often vulnerable workers and followers, and whose management favoured profit for the few. He demanded a system of government inspections and employer’s liability for death and injury, the forerunner of the later protective legislation. Chadwick had witnessed the destruction of working-class housing to make way for the railway, and feared that the promise of high wages would lure men to abandon their families who would be left to claim Parish Relief, or worse, on completion of works, would return home penniless and join the ranks of the able-bodied vagrant army so feared by middle-class Victorians, known as the Other.[2]

Pressure from Chadwick led to a Parliamentary Select Committee which called 32 witnesses, though few navvies. During the proceedings, admiration for two individual railway contractors was expressed, this formidable pair were Thomas Brassey and Samuel Morton Peto. One celebrated witness was Brunel, who spoke against the truck system and legislative interference, demanding reform from within the companies themselves. Despite the committee agreeing with Chadwick’s proposals, the matter was never brought before Parliament and again was quietly forgotten. Nevertheless, whilst Brunel and his team were constructing the Great Western Line, the two highly-successful contractors, Brassy and Peto, had emerged, understanding and respecting their navvy workforce. Praised by the Select Committee and by various Victorian primary sources both Thomas Brassey and Sir Samuel Morton Peto valued their experienced navvies, and their regard for their men bears testament to this. Non-conformist in belief, faith drove their behaviour and attitudes and was reflected in the loyalty they received in return.[3]

|

Thomas Brassey A protegee of George Stephenson, Thomas Brassey (1805 – 1870), was the first to take his trusted navvy workforce abroad, constructing over 6,415 miles of railway throughout Britain, Europe, Russia, Canada, Australia, and South America. At times, he had up to 80,000 men in his employ, and was adept at assembling armies of skilled labour, managing their rapid mobilisation from place to place.[4] Right: Thomas Brassey (1805 - 1870) |

Brassey developed a system of sub-contracting, allowing expertise to build up, in trades such as mining, bricklaying, carpentry and excavating. Originally used on canal construction, he approved of the system known as butty-gang (a group of buddies), where work was given to a gang of 10 to 15 navvies, for whom a price was agreed by the ganger and then divided amongst the group according to their experience. This system was later to come under some criticism, but was managed by Brassey and his team to the extent that, on later works, experienced navvies needed little supervision, requiring the engineer to verify their weekly work in order to claim their wages.[5] Brassey looked after his men, not as an itinerant labour workforce, but as a highly skilled mobile army. When word spread that he was fatally ill, his navvies waited patiently outside his home for news and a chance to pay their respects.

|

Revulsion to Hero-Status

Despite regard from these experts, the navvies were otherwise reviled or ignored. However, they were about to become the nation’s heroes. Sir Samuel Morton Peto, alleged to be a reformed alcoholic, believed that he had tamed his navvies by cloistering well-paid, well-fed workers in barracks, employing preachers and providing education in free time.[6] Indeed, in 1835, Brunel awarded Peto the contract for the construction of the Brent Viaduct, 7 miles from Paddington on the Great Western, not because he was the cheapest, but as one of the best. Despite this high regard, Brunel made life difficult for Peto by refusing interim payments and questioning the quality of the work. On completion of the contract, Peto long-remembered the humiliation he had suffered at the hands of Brunel and claimed that it was the only contract where no profit was made.[7] Left: Samuel Morton Peto |

In the Autumn of 1854, the British army was laying siege to the Crimean fort at Sevastopol and by December, the troops were freezing, starving and in rags. The only road was a muddy mire over which armaments, food, clothing and medicine could not travel. As the supply chain failed, so cholera arrived. The conditions were reported by The Times war correspondent, WH Russell, who was particularly critical of the management of the war, and there was much public consternation.

Now in Parliament and a Knight of the Realm, Sir Samuel Morton Peto proposed a railway linking the port of Balaklava to the beleaguered troops at Sevastopol. An offer to provide ships, men, and materials to engineer, build, and run the railway, was gratefully accepted by the government. Peto looked to his partner, Betts, and fellow contractor Thomas Brassey, for support. As the most powerful contractors in the world, they set about the organisation of the project which Brassey had agreed to manage at cost price.[8] Their formal offer to Parliament suggested the formation of a Civil Engineering Corps, composed of 350-400 able and steady navvies, tradesmen, clerks and engineers.[9] Just one stipulation was made, that under no circumstances was their workforce to come under military control, but would be commanded, at all times, by their chief engineer, James Beattie.[10]

Working in the Crimea

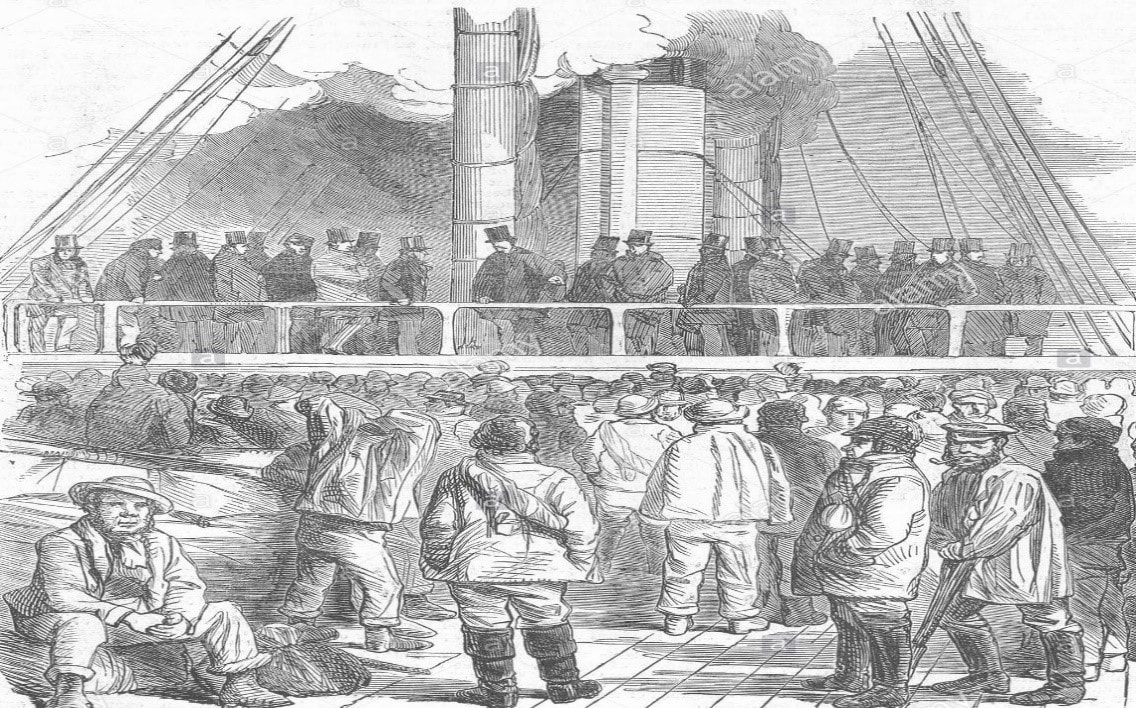

With the country behind the expedition, ships were put at their disposal, whilst several railway companies opened their stores for supplies. Men came forward, signing up for a six month’s contract at 5s a day. Historians Terry Coleman and David Brooke concur that many of the men, including Beattie, were previously engaged by Brassey in Canada and New Brunswick, and were prepared for the freezing conditions, whilst Sullivan argues that they were Peto’s men from the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway.[11] An enthusiastic crowd waved off the first contingent, and on seeing the physical appearance of these men, the Illustrated London News commented if ever these men came to hand to hand fighting with the enemy, they will fell them like ninepins.[12] Having signed Allotment Notes, authorising deductions from wages for wives and families, the navvies were supplied with a full kit comprised of a waterproof bag with bedding, a tent and stove, along with clothing including their preferred moleskin trousers, four pairs of waterproof boots and of course, tobacco. A quantity of revolvers accompanied the men and when reported, received much criticism from the press.[13] Peto and Brassey, both religious men, ensured that the navvies were accompanied by two missionaries and four nurses to administer to their spiritual and physical well-being.

As the second detachment left on the Hesperus, the navvies mustered on deck in their new clothing, to be addressed by Captain WS Andrews, Though accommodation found on board ship necessarily differs considerably from what you are accustomed to, yet nothing had been neglected that could contribute during the voyage to your comfort and the preservation of that health and strength on which so much reliance is placed, not only by your employers but by the whole country.[14] These navvies could no longer be classed as the Other, they were definitely Somebodies.

Let ashore in Malta without money, the Navvies held boxing matches and, cooped in their ships, there were personal disagreements and fights. However, once ashore at Balaklava, they set up a base, erected their huts, and tore down houses to clear a space for the railway lines. Unfortunately, they demolished the yard of the house belonging to the correspondent Russell, who returned home to find railway sleepers piled high where his courtyard had once stood. He never forgave the navvies.[15]

Seven miles of line were completed in six weeks, and by August many were on their way home. The navvies stopped work only once to complain that their rations of salt beef were not as they were used to, and Russell keenly reported the flogging of one navvy for the theft of a bullock. A new Corps of Navigators was on its way to run and maintain the line. Shortly after, James Beattie was involved in an accident, dying soon after arriving home. His widow received a war pension at colonel’s rates, probably arranged by Peto.[16] Brunel had also taken an interest in the Crimea, with Parliament accepting his offer to build a prefabricated hospital which could be shipped out in sections. Built by navvies who crossed the Black Sea to Scutari and Renkioi, it had modern facilities, sanitation and 1000 beds, where over 1500 wounded were treated before the declaration of peace.[17]

Now in Parliament and a Knight of the Realm, Sir Samuel Morton Peto proposed a railway linking the port of Balaklava to the beleaguered troops at Sevastopol. An offer to provide ships, men, and materials to engineer, build, and run the railway, was gratefully accepted by the government. Peto looked to his partner, Betts, and fellow contractor Thomas Brassey, for support. As the most powerful contractors in the world, they set about the organisation of the project which Brassey had agreed to manage at cost price.[8] Their formal offer to Parliament suggested the formation of a Civil Engineering Corps, composed of 350-400 able and steady navvies, tradesmen, clerks and engineers.[9] Just one stipulation was made, that under no circumstances was their workforce to come under military control, but would be commanded, at all times, by their chief engineer, James Beattie.[10]

Working in the Crimea

With the country behind the expedition, ships were put at their disposal, whilst several railway companies opened their stores for supplies. Men came forward, signing up for a six month’s contract at 5s a day. Historians Terry Coleman and David Brooke concur that many of the men, including Beattie, were previously engaged by Brassey in Canada and New Brunswick, and were prepared for the freezing conditions, whilst Sullivan argues that they were Peto’s men from the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway.[11] An enthusiastic crowd waved off the first contingent, and on seeing the physical appearance of these men, the Illustrated London News commented if ever these men came to hand to hand fighting with the enemy, they will fell them like ninepins.[12] Having signed Allotment Notes, authorising deductions from wages for wives and families, the navvies were supplied with a full kit comprised of a waterproof bag with bedding, a tent and stove, along with clothing including their preferred moleskin trousers, four pairs of waterproof boots and of course, tobacco. A quantity of revolvers accompanied the men and when reported, received much criticism from the press.[13] Peto and Brassey, both religious men, ensured that the navvies were accompanied by two missionaries and four nurses to administer to their spiritual and physical well-being.

As the second detachment left on the Hesperus, the navvies mustered on deck in their new clothing, to be addressed by Captain WS Andrews, Though accommodation found on board ship necessarily differs considerably from what you are accustomed to, yet nothing had been neglected that could contribute during the voyage to your comfort and the preservation of that health and strength on which so much reliance is placed, not only by your employers but by the whole country.[14] These navvies could no longer be classed as the Other, they were definitely Somebodies.

Let ashore in Malta without money, the Navvies held boxing matches and, cooped in their ships, there were personal disagreements and fights. However, once ashore at Balaklava, they set up a base, erected their huts, and tore down houses to clear a space for the railway lines. Unfortunately, they demolished the yard of the house belonging to the correspondent Russell, who returned home to find railway sleepers piled high where his courtyard had once stood. He never forgave the navvies.[15]

Seven miles of line were completed in six weeks, and by August many were on their way home. The navvies stopped work only once to complain that their rations of salt beef were not as they were used to, and Russell keenly reported the flogging of one navvy for the theft of a bullock. A new Corps of Navigators was on its way to run and maintain the line. Shortly after, James Beattie was involved in an accident, dying soon after arriving home. His widow received a war pension at colonel’s rates, probably arranged by Peto.[16] Brunel had also taken an interest in the Crimea, with Parliament accepting his offer to build a prefabricated hospital which could be shipped out in sections. Built by navvies who crossed the Black Sea to Scutari and Renkioi, it had modern facilities, sanitation and 1000 beds, where over 1500 wounded were treated before the declaration of peace.[17]

Back in Britain, as Victorian public works progressed so did public perception of the navvy. Fuelled by their stoic efforts in the Crimea and the realisation that an experienced navvy workforce was required to construct the great sewer system designed by Joseph Bazalgette. This element of respect was clearly demonstrated in one of the finest of the Pre-Raphaelite paintings, Work by Ford Madox Brown. An allegory of the British class system, the painting is a celebration of honest labour, demonstrated by the young navvy bathed in light at the centre of the painting.

Sudbrook and the Severn Railway Tunnel

In the last decades of the great 19th century, with South Wales at the heart of the Empire’s powerhouse, the dream of a railway tunnel under the River Severn, linking England to Wales along the Great Western line, was finally completed by the contractor Thomas Walker and his navvy workforce under the supervision of the engineer, Sir John Hawkshaw. The tunnel was originally the idea of Brunel’s pupil, Charles Richardson who had been responsible for the trial shafts at Box.[18]

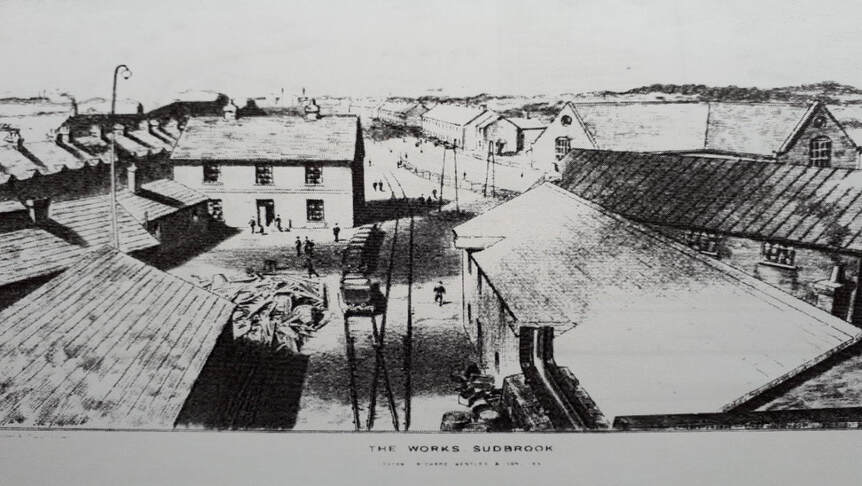

To house his workforce, Walker had a solidly-constructed navvy village now called Sudbrook built on the Welsh side, which is still very much a thriving community proud of its navvy heritage. It should come as no surprise that the navvy families arrived by train, the foremen first, perhaps with furniture, prams, birdcages, beds and other things too numerous to mention, as they did on the Kettering to Manton Line in Northamptonshire.[19] Far removed in comfort and facilities from most navvy communities, the village of Sudbrook was built between 1873 and 1886, housing up to 1,987 workers and their families.[20] Walker, also deeply religious like his mentor Brassey, built a mission hall, school, hospital, reading room and cottages. The imposing pumping station, constructed to prevent the tunnel flooding, is still in use and visible as you cross the Severn on the Prince of Wales Bridge.

In the last decades of the great 19th century, with South Wales at the heart of the Empire’s powerhouse, the dream of a railway tunnel under the River Severn, linking England to Wales along the Great Western line, was finally completed by the contractor Thomas Walker and his navvy workforce under the supervision of the engineer, Sir John Hawkshaw. The tunnel was originally the idea of Brunel’s pupil, Charles Richardson who had been responsible for the trial shafts at Box.[18]

To house his workforce, Walker had a solidly-constructed navvy village now called Sudbrook built on the Welsh side, which is still very much a thriving community proud of its navvy heritage. It should come as no surprise that the navvy families arrived by train, the foremen first, perhaps with furniture, prams, birdcages, beds and other things too numerous to mention, as they did on the Kettering to Manton Line in Northamptonshire.[19] Far removed in comfort and facilities from most navvy communities, the village of Sudbrook was built between 1873 and 1886, housing up to 1,987 workers and their families.[20] Walker, also deeply religious like his mentor Brassey, built a mission hall, school, hospital, reading room and cottages. The imposing pumping station, constructed to prevent the tunnel flooding, is still in use and visible as you cross the Severn on the Prince of Wales Bridge.

|

Walker compiled a report on the construction of the tunnel and village, with detailed diagrams of the workings in the tunnel and the village, infirmary and fever hospital. Walker wrote that considering the magnitude of the undertaking, the difficulties encountered and the number of men working night and day, there were few accidents.[21] Nevertheless, the navvies suffered from lung disease, rheumatic fever and pneumonia brought on by the heat and damp in the tunnel, and as such, the fever hospital was busy. However circumspect Walker may have been, the tunnel was a dangerous environment in which to work and accidents did occur. Human error was to blame when in February 1883, an iron skip was mistakenly pushed 110 feet into a shaft crushing a cage and the men in it, which then rebounded killing another and severely injuring two others. Later that year, a great storm produced a tidal wave which engulfed some of the workers' cottages and left 83 men stranded at the bottom of the pump shaft. Once the tide had retreated, a rescue attempt was made, and miraculously, all were saved.

|

During construction there was an inevitable strain on the water pumps which led to flooding in the tunnel, slowing progress and placing the men in danger. Walker’s chief diver, Alexander Lambert, made several aborted attempts to investigate the cause of the flooding. However, his primitive air hose system was never robust enough to withstand the poor conditions. Walker who made use of technical innovation, called upon the experienced diving engineer, Wiltshire-born Dr Henry Fleuss, who in 1878 had patented underwater rebreathers consisting of a rubber mask connected to a breathing bag which gave a diving duration of three hours. Trained by Fleuss, Lambert became the first man to successfully use the apparatus under operational conditions and later used it on several further rescue missions.[22]

Navvy Families at Sudbrook

Using parish records, census returns and recently available school registers, local historian Robert Gant has researched the lives of the navvy families and their migration from work on the tunnel to other contracts of Walker’s. In 1882 just 300 men were employed in the tunnel; by 1884 the number had increased to 3,628 men of all trades. Walker provides a breakdown of the trades employed and the wages paid to each trade. These workers were well-paid in comparison with local agricultural workers, and the availability of unskilled work attracted men from the surrounding areas who, Gant points out, were lodged in nearby villages rather than in Sudbrook which housed his skilled navvies and families in large terraced properties built from stone excavated from the tunnel. Trades lodged with trades, wives and daughters fulfilling domestic duties.

Navvy Families at Sudbrook

Using parish records, census returns and recently available school registers, local historian Robert Gant has researched the lives of the navvy families and their migration from work on the tunnel to other contracts of Walker’s. In 1882 just 300 men were employed in the tunnel; by 1884 the number had increased to 3,628 men of all trades. Walker provides a breakdown of the trades employed and the wages paid to each trade. These workers were well-paid in comparison with local agricultural workers, and the availability of unskilled work attracted men from the surrounding areas who, Gant points out, were lodged in nearby villages rather than in Sudbrook which housed his skilled navvies and families in large terraced properties built from stone excavated from the tunnel. Trades lodged with trades, wives and daughters fulfilling domestic duties.

In the years of construction, 284 navvy families with 922 children were living at Sudbrook. The children were schooled, received religious instruction and medical care when required. By examining school logs, Gant traced children from Sudbrook to Walker’s other construction sites, such as the Manchester Ship Canal, moving as their father’s expertise was required, and in a few cases, back to Sudbrook.[23] Migration of navvies with a particular skill had become a sophisticated operation and far removed from the itinerant and lawless lifestyle so associated with the navvies, and experienced at Box some forty years previously.

Walker’s reputation as a good employer was also evident on other contracts including the Manchester Ship Canal, where he employed watchmen known as fragments (those injured whilst working in the tunnel).[24] Walker also managed the building of Barry Docks in South Wales, where, as the 19th century drew to a close, the navvies were confident enough in their ability to strike for better wages, and where one engineer was none other than Henry Marc Brunel, son of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Public Recognition

At the turn of the century, a navvy, John Ward, became the Member of Parliament for Stoke-on-Trent and campaigned against Chinese labour in the gold mines of South Africa, condemning it as slavery. He had been an official in the newly-formed Gas and Navvies’ Association, a liberal-backed union. Young and old navvies joined up during the Great War and were especially useful in the Labour Battalions, digging, not only trenches, but railway and communication lines. John Ward, who had been personally recruited by Kitchener, raised four battalions, known as the Public Works Pioneers, made up of navvies, they served at the Somme and later, at Salonika.[25]

The navvies came home from war to a changed Britain. Public works were few and far between, and the recruitment of labour had become bureaucratic. The lowly, lawless navvy had been finally fully integrated into society.

Walker’s reputation as a good employer was also evident on other contracts including the Manchester Ship Canal, where he employed watchmen known as fragments (those injured whilst working in the tunnel).[24] Walker also managed the building of Barry Docks in South Wales, where, as the 19th century drew to a close, the navvies were confident enough in their ability to strike for better wages, and where one engineer was none other than Henry Marc Brunel, son of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Public Recognition

At the turn of the century, a navvy, John Ward, became the Member of Parliament for Stoke-on-Trent and campaigned against Chinese labour in the gold mines of South Africa, condemning it as slavery. He had been an official in the newly-formed Gas and Navvies’ Association, a liberal-backed union. Young and old navvies joined up during the Great War and were especially useful in the Labour Battalions, digging, not only trenches, but railway and communication lines. John Ward, who had been personally recruited by Kitchener, raised four battalions, known as the Public Works Pioneers, made up of navvies, they served at the Somme and later, at Salonika.[25]

The navvies came home from war to a changed Britain. Public works were few and far between, and the recruitment of labour had become bureaucratic. The lowly, lawless navvy had been finally fully integrated into society.

References

[1] David Brooke, The Railway Navvy, That Despicable Race of Men, Newton Abbot, David & Charles, 1983

[2] RA Lewis, Edwin Chadwick and the Railway Labourers, 1950, New Series, Vol:3, No 1, p.108

[3] LM Evans, Navvies and Their Needs, Leopold Classic Library, originally published in Leeds by J.W Petty & Sons, 1878, reprinted from The Quiver, pp.6–9,

[4] Arthur Helps, Life and Labours of Mr Brassey, (New York: Augustus. M Kelley, 1872) this edition published by Evelyn, Adams and Mackay Ltd, 1969, p IX, p 81, p.27

[5] Frederick Smeeton Williams, Our Iron Roads, Their history, Construction and Administration, (London: Bemrose and Son, 1883), this version printed by Forgotten Books, p.149

[6] Adrian Vaughan, Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, 2009, Hersham Ian Allen Publishing, p.79

[7] Adrian Vaughan, Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, pp.21-22

[8] Terry Coleman, The Railway Navvies, 1968, Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, p.213

[9] Peto, Brassey & Co, to Duke of Newcastle, 30th November 1854, Correspondence on the Construction of a Railway from Balaklava to Sebastopol, Parliamentary Papers, 1854 – 55, XXXII, quoted in Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, by Adrian Vaughan, 2009. Hersham: Ian Allen Publishing, p.134

[10] David Brooke, The Railway Navvy, That Despicable Race of Men, p.124

[11] Dick Sullivan, Navvyman, 1983, London: Coracle, p.144

[12] Illustrated London News, 9 December, 1854

[13] Terry Coleman, The Railway Navvies, p.216

[14] Illustrated London News, 13 January, 1855

[15] Dick Sullivan, Navvyman, p.145

[16] Adrian Vaughan, Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, p.137

[17] LTC Rolt, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, A Biography, London: Longmans, p.157

[18] Thomas Andrew Walker, The Severn Tunnel: Its Construction and Difficulties, 1872–1887, 1980, Primary source edition, originally published by Richard Bentley & Son, 1890

[19] D W Barrett, Life and Work Among the Navvies, (London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co, 1880) p.65

[20] Robert Gant, School Records, Family Migration and Community History: Insights from Sudbrook and the Construction of the Severn Tunnel, Family and Community History, Vol 11/1, May 2008

[21] Thomas Andrew Walker, The Severn Tunnel: Its Construction and Difficulties, p.106

[22] En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Fleuss

[23] Thomas Andrew Walker, The Severn Tunnel: Its Construction and Difficulties, p.32.

[24] Anthony Burton, Navvies, History’s Most Dangerous Jobs, 2012, Stroud, The History Press, p.143

[25] Dick Sullivan, Navvyman, pp.194 - 218

[1] David Brooke, The Railway Navvy, That Despicable Race of Men, Newton Abbot, David & Charles, 1983

[2] RA Lewis, Edwin Chadwick and the Railway Labourers, 1950, New Series, Vol:3, No 1, p.108

[3] LM Evans, Navvies and Their Needs, Leopold Classic Library, originally published in Leeds by J.W Petty & Sons, 1878, reprinted from The Quiver, pp.6–9,

[4] Arthur Helps, Life and Labours of Mr Brassey, (New York: Augustus. M Kelley, 1872) this edition published by Evelyn, Adams and Mackay Ltd, 1969, p IX, p 81, p.27

[5] Frederick Smeeton Williams, Our Iron Roads, Their history, Construction and Administration, (London: Bemrose and Son, 1883), this version printed by Forgotten Books, p.149

[6] Adrian Vaughan, Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, 2009, Hersham Ian Allen Publishing, p.79

[7] Adrian Vaughan, Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, pp.21-22

[8] Terry Coleman, The Railway Navvies, 1968, Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, p.213

[9] Peto, Brassey & Co, to Duke of Newcastle, 30th November 1854, Correspondence on the Construction of a Railway from Balaklava to Sebastopol, Parliamentary Papers, 1854 – 55, XXXII, quoted in Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, by Adrian Vaughan, 2009. Hersham: Ian Allen Publishing, p.134

[10] David Brooke, The Railway Navvy, That Despicable Race of Men, p.124

[11] Dick Sullivan, Navvyman, 1983, London: Coracle, p.144

[12] Illustrated London News, 9 December, 1854

[13] Terry Coleman, The Railway Navvies, p.216

[14] Illustrated London News, 13 January, 1855

[15] Dick Sullivan, Navvyman, p.145

[16] Adrian Vaughan, Samuel Morton Peto, A Victorian Entrepreneur, p.137

[17] LTC Rolt, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, A Biography, London: Longmans, p.157

[18] Thomas Andrew Walker, The Severn Tunnel: Its Construction and Difficulties, 1872–1887, 1980, Primary source edition, originally published by Richard Bentley & Son, 1890

[19] D W Barrett, Life and Work Among the Navvies, (London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co, 1880) p.65

[20] Robert Gant, School Records, Family Migration and Community History: Insights from Sudbrook and the Construction of the Severn Tunnel, Family and Community History, Vol 11/1, May 2008

[21] Thomas Andrew Walker, The Severn Tunnel: Its Construction and Difficulties, p.106

[22] En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Fleuss

[23] Thomas Andrew Walker, The Severn Tunnel: Its Construction and Difficulties, p.32.

[24] Anthony Burton, Navvies, History’s Most Dangerous Jobs, 2012, Stroud, The History Press, p.143

[25] Dick Sullivan, Navvyman, pp.194 - 218