Medieval Box Church Alan Payne February 2024

The authority of the medieval church was shaken by the Black Death and later plagues but its spiritual role in society was undiminished and investment in the building in Box substantially altered is size and its appearance of grandeur to residents.

Decline of Monkton Farleigh

Whilst Box parish church experienced development, its mother church Monkton Farleigh was in decline. The monastic institutions had previously been the source of knowledge through literacy; now they had no answers or explanations to the judgement of God and His punishment for man’s sinfulness. Local clergy who administered the last rites to plague victims were decimated. Many of the dead were buried without absolution in mass graves, and Pope Clement VI had to offer a general remission for those dying without the last rites. Respect for the clergy was tested in the 1300s. Henry Knighton in Leicester described parish priests: even if they could read, they did not understand.[1] We have the names of some of the vicars in Box in the 1300s but no knowledge of their ability or their role in the village.[2]

The lack of education of lay clergy bred dissatisfaction and John Wycliffe translated he Bible into English and questioned the authority of the Roman Church and the privileges of parish priests. His work in the late 1300s was continued by the Lollards, a Protestant organisation which toured areas for decades as an underground sect. A similar call to action existed with groups such as the Flagellants, who sought to atone for man’s sins by whipping themselves in public.

The monasteries and abbeys were particularly hard hit by the Black Death, probably including Lawrence Archebaud, prior of Monkton Farleigh.[3] The role of monastic houses as medieval hospices (guest houses cum hospitals) meant they were breeding grounds for the plague which spread through their entire communities. There are suggestions that Monkton Farleigh was reduced to a handful of monks after the plague.

The role of the Cluniac Order in England was redefined by the king, especially during the Hundred Years War between England and France. The king’s needs were primarily for money and foreign monasteries were easy prey, starting in 1294 when several were taken into royal ownership by Edward I. In 1337 Edward III started a more systematic seizure of the revenues of alien priories in England. He confiscated their income from rents, imposed taxation of tenths (10% of the value of land and movables), wool, tithes and other quotas and dues and used the money to pay his army and other military purposes. He achieved this by farming out rental incomes to local landholders as custodian (in some areas to the prior himself) who paid an up-front fee and pocketed any surplus.[4] At times, the king himself took over control of the priories to exact a higher fee.

The authority of Monkton Farleigh was further diminished by the Great Schism of 1378 when the mother church at Cluny accepted control by the Pope at Avignon, whilst the English Church continued to recognise Rome. There were several alien expulsions of individuals in that year. It would be reasonable to assume that the role of Monkton Farleigh Priory in Box was substantially affected by these events. By the time of its dissolution in 1536, the Priory numbered only six monks.[5]

Role of the Parish Church

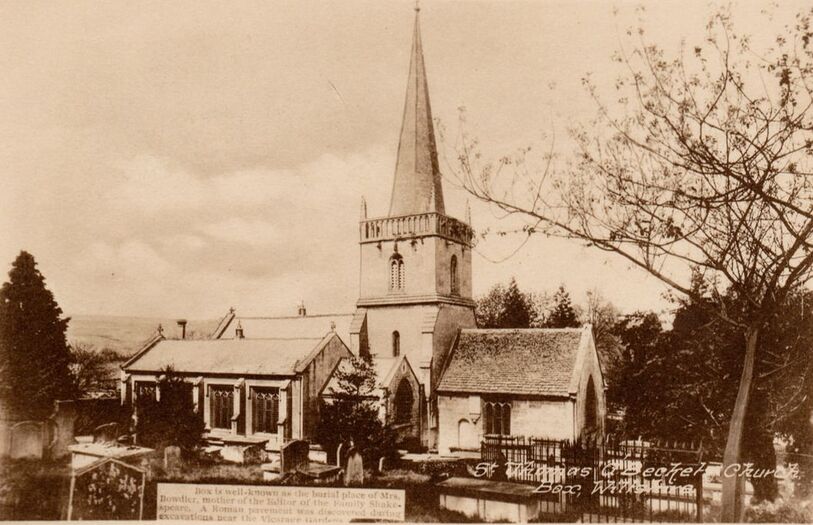

Box Church developed significantly in the 1300s to 1500s when it was altered from an Early English style of architecture to a Late Perpendicular Gothic appearance.[6] Unfortunately, there is no indication who funded the work, although we can note that it was during a period of absentee lordship and the decline of Monkton Farleigh Priory. The Black Death had encouraged greater personal piety with a growth in pilgrimages and the foundation of local chantries (a place where a priest could chant masses for the souls of the founder and the dead in Purgatory). Horton’s chantry in Bradford was endowed with land in Box.[7] As late as 1503, one of the leading nobles in the village, John Bonham of Hazelbury, left 6s.8d plus his best cow to John Stone, Prior of Monkton Farleigh, with the requirement to: recommend his soul on Sundays amongst others.[8]

The importance of Box Church was demonstrated by the massive amount of work undertaken on the fabric of the building after the 1300s.[9] The Chancel, the most sacred part of the church, was opened up by the creation of arches cut through the tower on the east and west transepts. It would have involved considerable structural work to correctly transfer the tower’s weight and to finish the alterations with a new archway. Work on that scale led to further alterations, including a wider rood screen and a new two-storey north aisle (now demolished). The tower work was to accommodate tolling bells. As well as publicising the church services, it was believed that church bells warded off thunder and lightning if they were rung during storms.[10] To balance proportions, an extension to the nave was built in the west of the church. Other work around this time included the font which was replaced, probably made locally because it is identical to those in Corsham and Colerne.[11] The font had a special status through the rite of baptism to exorcise evil from newly-born children and its renewal was a highly symbolic regeneration of the church.[12]

In theory, the maintenance of the fabric of the building was shared between the parishioners and Farleigh Priory.[13] The rector (the prior of Monkton Farleigh) was responsible for the chancel behind the elaborately carved rood screen with its crucifix and wooden statues of saints. The parishioners (including the lord of the manor) were responsible for work on the nave and the maintenance of the churchyard, and the bounds and gates of the vicarage.[14] However, there must be an assumption that work of this extent was beyond the financial capabilities of the parishioners and outside of their responsibility. Could the builder have been the Moleyns family?

Everyday Religion in Box

Box parish church took the lead role in everyday village life both in terms of religious ceremony and celebrations. Before the Reformation, Box Church practised the Roman Catholic traditions and celebrated the mass and all services in Latin.[15] Originally the services were conducted on the floor of the church, but pulpits and lecterns were introduced in the late 1400s, separating the priest from the congregation. There were no seats or pews for the congregation who stood or kneeled in the centre of the nave during services, allowing the old or infirm to ‘go to the wall’ for support. In an age of low levels of literacy most people understood the Bible from spoken words or the highly colourful painted walls and stained glass which graphically illustrate Biblical stories. Hazelbury chapel has patches of its original bright red paint and remnants of a wall painting behind the

chapel altar.[16]

In the 1400s, the annual calendar was measured out by religious days of fasting or feast and villagers participated by raising funds to support the ritual of candles, processions and dressing up to commemorate religious life.[17] Regular attendance at communion was expected; the kiss of peace before mass was part of the duty of being a good citizen and neighbour. Parishioners wanted to have an active involvement and to invest in Box Church. Churches required the active participation of the laity to avoid the steep decline at Hazelbury Church, where the church was abandoned for lack of population. To do this they organised fundraising celebrations.

Advent for the four weeks leading to Christmas was a period of fasting restricted to stinking fish not worth a louse. Christmas Eve was strict diet without meat, cheese or eggs; then followed twelve days of feastings, mummer plays, and misbehaviour with the Lord of Misrule (sometimes called Jack Straw after the name of a leader in the Peasants Revolt of 1381). Houses were decorated with holly and ivy and the Church was wonderfully lit with candle lights. Twelfth Night (6 January) was the feast of Epiphany when Christ was recognised by the Three Kings and a star of Bethlehem made from brass or gilded wood erected in the church. After Epiphany was the time to prepare for work. The communal ploughs were paraded around the village with dancing and fundraising. The ploughs were placed in the church and a special plough candle was lit to commemorate their importance. Candlemas (2 February) was to celebrate the lengthening daylight and the formal end of winter when tapers and candles were placed before the altar, sprinkled with holy water and incense.

Lent started on Shrove Tuesday, a time to eat food stocks and to enjoy ball games and cock fighting before the seven weeks of Lent, a period of fasting and deep sobriety. The rood screen showing Christ and the Apostles was covered by a cloth mounted on a wooden loft and the altar was covered in a white veil to be revealed only at mass. On Palm Sunday, commemorating Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, the priest replaced his white robes for red and evergreen tree branches were processed in the churchyard by parishioners. The priest removed the cloths over the rood screen and the altar to great celebration. Easter Holy Week started on Maundy Thursday to celebrate the Last Supper. Good Friday commemorating the entombment of Christ was depicted by a miniature sepulchre in the church surrounded by candles. On Easter Saturday all candles were extinguished and after dark the priest struck a new flame and lit the great Paschal candle in a great metal candlestick. The sepulchre was opened on Easter Day re-enacting the empty tomb after Christ’s rising from the dead, followed by mass.

Residents could be actively involved in the church through local guilds. Sometimes they catered for the whole community of the parish like the Guild of Corpus Christi; sometimes for specific groups of people, like craftsmen, labourers or women. They prayed for the souls of the departed at times of grief and they organised seasonal festivals and street processions. The Revel to St Thomas à Becket was on 7th July to celebrate the patron saint's day. People assembled in the church, children re-enacted the martyrdom of the saint and there was a formal march in procession to St Thomas’ Well on the Bath Road near the Bear Hotel and back for mass in the church.[18] It was part of the entertainment sanctioned by the church for holy days and for fund raising from parishioners.

May games and ales were a major source of fundraising.[19] Mayday ale crawls sometimes involved visits to other local parish churches; the crowning of mock kings and queens accompanied by travelling players; and frequent plays about Robin Hood.

The Robin Hood character was the ideal lord of misrule, as befitted an outlaw, and the enactment of his legend became widespread and very popular in the late Middle Ages. On May Day and at Whitsuntide there were celebrations with music, Morris dancing and a maypole. Sometimes there were miracle plays performed by Box’s villagers or by a company of travelling players.

John Aubrey recalled activities in Kington St Michael, Chippenham, in his grandfather's day that probably mirrored activity in Box: The Church Ale at Whitsuntide did their businessse. In every Parish is, or was, a church howse, to which belonged spitts, crocks, etc, utensils for dressing provision. Here the Howsekeepers met, and were merry and gave their Charitie: the young people came there too, and had dancing, bowling, shooting at buttes, etc, the ancients sitting gravely by, looking on. All things were civill and without scandall.[20]

The church also offered support in times of need by selling marriage ales or help ales. The church building was used for a variety of purposes, many of which we would regard as secular or non-religious. Wedding parties with dancing and other entertainment took place within the church, whilst the wedding ceremony itself was held on the porch, after which the couple entered the building to celebrate mass. Fairs and markets centred on the church.

The church defined the area of the parish. On the sixth Monday after Easter a Rogation procession around the village and its boundaries asked God’s blessing for the parish and its crops (rogare in Latin meaning ‘to ask’). The procession was a formal affair led by the priest and an image of Christ or the Virgin, preceded by minstrels, followed by the parishioners with banners representing local guilds.[21]

Decline of Monkton Farleigh

Whilst Box parish church experienced development, its mother church Monkton Farleigh was in decline. The monastic institutions had previously been the source of knowledge through literacy; now they had no answers or explanations to the judgement of God and His punishment for man’s sinfulness. Local clergy who administered the last rites to plague victims were decimated. Many of the dead were buried without absolution in mass graves, and Pope Clement VI had to offer a general remission for those dying without the last rites. Respect for the clergy was tested in the 1300s. Henry Knighton in Leicester described parish priests: even if they could read, they did not understand.[1] We have the names of some of the vicars in Box in the 1300s but no knowledge of their ability or their role in the village.[2]

The lack of education of lay clergy bred dissatisfaction and John Wycliffe translated he Bible into English and questioned the authority of the Roman Church and the privileges of parish priests. His work in the late 1300s was continued by the Lollards, a Protestant organisation which toured areas for decades as an underground sect. A similar call to action existed with groups such as the Flagellants, who sought to atone for man’s sins by whipping themselves in public.

The monasteries and abbeys were particularly hard hit by the Black Death, probably including Lawrence Archebaud, prior of Monkton Farleigh.[3] The role of monastic houses as medieval hospices (guest houses cum hospitals) meant they were breeding grounds for the plague which spread through their entire communities. There are suggestions that Monkton Farleigh was reduced to a handful of monks after the plague.

The role of the Cluniac Order in England was redefined by the king, especially during the Hundred Years War between England and France. The king’s needs were primarily for money and foreign monasteries were easy prey, starting in 1294 when several were taken into royal ownership by Edward I. In 1337 Edward III started a more systematic seizure of the revenues of alien priories in England. He confiscated their income from rents, imposed taxation of tenths (10% of the value of land and movables), wool, tithes and other quotas and dues and used the money to pay his army and other military purposes. He achieved this by farming out rental incomes to local landholders as custodian (in some areas to the prior himself) who paid an up-front fee and pocketed any surplus.[4] At times, the king himself took over control of the priories to exact a higher fee.

The authority of Monkton Farleigh was further diminished by the Great Schism of 1378 when the mother church at Cluny accepted control by the Pope at Avignon, whilst the English Church continued to recognise Rome. There were several alien expulsions of individuals in that year. It would be reasonable to assume that the role of Monkton Farleigh Priory in Box was substantially affected by these events. By the time of its dissolution in 1536, the Priory numbered only six monks.[5]

Role of the Parish Church

Box Church developed significantly in the 1300s to 1500s when it was altered from an Early English style of architecture to a Late Perpendicular Gothic appearance.[6] Unfortunately, there is no indication who funded the work, although we can note that it was during a period of absentee lordship and the decline of Monkton Farleigh Priory. The Black Death had encouraged greater personal piety with a growth in pilgrimages and the foundation of local chantries (a place where a priest could chant masses for the souls of the founder and the dead in Purgatory). Horton’s chantry in Bradford was endowed with land in Box.[7] As late as 1503, one of the leading nobles in the village, John Bonham of Hazelbury, left 6s.8d plus his best cow to John Stone, Prior of Monkton Farleigh, with the requirement to: recommend his soul on Sundays amongst others.[8]

The importance of Box Church was demonstrated by the massive amount of work undertaken on the fabric of the building after the 1300s.[9] The Chancel, the most sacred part of the church, was opened up by the creation of arches cut through the tower on the east and west transepts. It would have involved considerable structural work to correctly transfer the tower’s weight and to finish the alterations with a new archway. Work on that scale led to further alterations, including a wider rood screen and a new two-storey north aisle (now demolished). The tower work was to accommodate tolling bells. As well as publicising the church services, it was believed that church bells warded off thunder and lightning if they were rung during storms.[10] To balance proportions, an extension to the nave was built in the west of the church. Other work around this time included the font which was replaced, probably made locally because it is identical to those in Corsham and Colerne.[11] The font had a special status through the rite of baptism to exorcise evil from newly-born children and its renewal was a highly symbolic regeneration of the church.[12]

In theory, the maintenance of the fabric of the building was shared between the parishioners and Farleigh Priory.[13] The rector (the prior of Monkton Farleigh) was responsible for the chancel behind the elaborately carved rood screen with its crucifix and wooden statues of saints. The parishioners (including the lord of the manor) were responsible for work on the nave and the maintenance of the churchyard, and the bounds and gates of the vicarage.[14] However, there must be an assumption that work of this extent was beyond the financial capabilities of the parishioners and outside of their responsibility. Could the builder have been the Moleyns family?

Everyday Religion in Box

Box parish church took the lead role in everyday village life both in terms of religious ceremony and celebrations. Before the Reformation, Box Church practised the Roman Catholic traditions and celebrated the mass and all services in Latin.[15] Originally the services were conducted on the floor of the church, but pulpits and lecterns were introduced in the late 1400s, separating the priest from the congregation. There were no seats or pews for the congregation who stood or kneeled in the centre of the nave during services, allowing the old or infirm to ‘go to the wall’ for support. In an age of low levels of literacy most people understood the Bible from spoken words or the highly colourful painted walls and stained glass which graphically illustrate Biblical stories. Hazelbury chapel has patches of its original bright red paint and remnants of a wall painting behind the

chapel altar.[16]

In the 1400s, the annual calendar was measured out by religious days of fasting or feast and villagers participated by raising funds to support the ritual of candles, processions and dressing up to commemorate religious life.[17] Regular attendance at communion was expected; the kiss of peace before mass was part of the duty of being a good citizen and neighbour. Parishioners wanted to have an active involvement and to invest in Box Church. Churches required the active participation of the laity to avoid the steep decline at Hazelbury Church, where the church was abandoned for lack of population. To do this they organised fundraising celebrations.

Advent for the four weeks leading to Christmas was a period of fasting restricted to stinking fish not worth a louse. Christmas Eve was strict diet without meat, cheese or eggs; then followed twelve days of feastings, mummer plays, and misbehaviour with the Lord of Misrule (sometimes called Jack Straw after the name of a leader in the Peasants Revolt of 1381). Houses were decorated with holly and ivy and the Church was wonderfully lit with candle lights. Twelfth Night (6 January) was the feast of Epiphany when Christ was recognised by the Three Kings and a star of Bethlehem made from brass or gilded wood erected in the church. After Epiphany was the time to prepare for work. The communal ploughs were paraded around the village with dancing and fundraising. The ploughs were placed in the church and a special plough candle was lit to commemorate their importance. Candlemas (2 February) was to celebrate the lengthening daylight and the formal end of winter when tapers and candles were placed before the altar, sprinkled with holy water and incense.

Lent started on Shrove Tuesday, a time to eat food stocks and to enjoy ball games and cock fighting before the seven weeks of Lent, a period of fasting and deep sobriety. The rood screen showing Christ and the Apostles was covered by a cloth mounted on a wooden loft and the altar was covered in a white veil to be revealed only at mass. On Palm Sunday, commemorating Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, the priest replaced his white robes for red and evergreen tree branches were processed in the churchyard by parishioners. The priest removed the cloths over the rood screen and the altar to great celebration. Easter Holy Week started on Maundy Thursday to celebrate the Last Supper. Good Friday commemorating the entombment of Christ was depicted by a miniature sepulchre in the church surrounded by candles. On Easter Saturday all candles were extinguished and after dark the priest struck a new flame and lit the great Paschal candle in a great metal candlestick. The sepulchre was opened on Easter Day re-enacting the empty tomb after Christ’s rising from the dead, followed by mass.

Residents could be actively involved in the church through local guilds. Sometimes they catered for the whole community of the parish like the Guild of Corpus Christi; sometimes for specific groups of people, like craftsmen, labourers or women. They prayed for the souls of the departed at times of grief and they organised seasonal festivals and street processions. The Revel to St Thomas à Becket was on 7th July to celebrate the patron saint's day. People assembled in the church, children re-enacted the martyrdom of the saint and there was a formal march in procession to St Thomas’ Well on the Bath Road near the Bear Hotel and back for mass in the church.[18] It was part of the entertainment sanctioned by the church for holy days and for fund raising from parishioners.

May games and ales were a major source of fundraising.[19] Mayday ale crawls sometimes involved visits to other local parish churches; the crowning of mock kings and queens accompanied by travelling players; and frequent plays about Robin Hood.

The Robin Hood character was the ideal lord of misrule, as befitted an outlaw, and the enactment of his legend became widespread and very popular in the late Middle Ages. On May Day and at Whitsuntide there were celebrations with music, Morris dancing and a maypole. Sometimes there were miracle plays performed by Box’s villagers or by a company of travelling players.

John Aubrey recalled activities in Kington St Michael, Chippenham, in his grandfather's day that probably mirrored activity in Box: The Church Ale at Whitsuntide did their businessse. In every Parish is, or was, a church howse, to which belonged spitts, crocks, etc, utensils for dressing provision. Here the Howsekeepers met, and were merry and gave their Charitie: the young people came there too, and had dancing, bowling, shooting at buttes, etc, the ancients sitting gravely by, looking on. All things were civill and without scandall.[20]

The church also offered support in times of need by selling marriage ales or help ales. The church building was used for a variety of purposes, many of which we would regard as secular or non-religious. Wedding parties with dancing and other entertainment took place within the church, whilst the wedding ceremony itself was held on the porch, after which the couple entered the building to celebrate mass. Fairs and markets centred on the church.

The church defined the area of the parish. On the sixth Monday after Easter a Rogation procession around the village and its boundaries asked God’s blessing for the parish and its crops (rogare in Latin meaning ‘to ask’). The procession was a formal affair led by the priest and an image of Christ or the Virgin, preceded by minstrels, followed by the parishioners with banners representing local guilds.[21]

References

[1] Tom Jones, BBC History in Depth: The Black Death

[2] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket, Box, 1987, Appendix I

[3] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket, Box, 1987, p.2

[4] Ben Peterson, The Handling of Alien Priories in England 1337-1360, 2011, p.7-8 71969778.pdf (core.ac.uk)

[5] The Papal Schism of 1378 and the English Province of the Order of Cluny on JSTOR

[6] Harold Lewis, The Church Rambler, 1876, p.10: https://ia802604.us.archive.org/10/items/churchrambleras01lewigoog/churchrambleras01lewigoog.pdf

[7] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol V, p.223

[8] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XX, p.230, Appendix D

[9] See further details at Thomas à Becket Church. Also, Harold Lewis, The Church Rambler, 1876: https://ia802604.us.archive.org/10/items/churchrambleras01lewigoog/churchrambleras01lewigoog.pdf

[10] Wiltshire Churches, p.82

[11] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984, p.7

[12] Wiltshire Churches, p.61

[13] Wiltshire Churches, p.37

[14] Steven Hobbs, Wiltshire Glebe Terriers 1588-1827, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 56, 2003, p.42

[15] Wiltshire Churches, p.67-73

[16] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984, p.5

[17] This section is indebted to Ronald Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England, 1994, OUP, p.7-47

[18] Parish Magazine, July 1929

[19] Ronald Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England, p.28

[20] John Aubrey, The Natural History of Wiltshire, 1656 and 1691, David & Charles Reprint, 1969

[21] Ronald Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England, p.36

[1] Tom Jones, BBC History in Depth: The Black Death

[2] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket, Box, 1987, Appendix I

[3] David Ibberson, The Vicars of St Thomas à Becket, Box, 1987, p.2

[4] Ben Peterson, The Handling of Alien Priories in England 1337-1360, 2011, p.7-8 71969778.pdf (core.ac.uk)

[5] The Papal Schism of 1378 and the English Province of the Order of Cluny on JSTOR

[6] Harold Lewis, The Church Rambler, 1876, p.10: https://ia802604.us.archive.org/10/items/churchrambleras01lewigoog/churchrambleras01lewigoog.pdf

[7] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol V, p.223

[8] Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XX, p.230, Appendix D

[9] See further details at Thomas à Becket Church. Also, Harold Lewis, The Church Rambler, 1876: https://ia802604.us.archive.org/10/items/churchrambleras01lewigoog/churchrambleras01lewigoog.pdf

[10] Wiltshire Churches, p.82

[11] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984, p.7

[12] Wiltshire Churches, p.61

[13] Wiltshire Churches, p.37

[14] Steven Hobbs, Wiltshire Glebe Terriers 1588-1827, Wiltshire Record Society, Vol 56, 2003, p.42

[15] Wiltshire Churches, p.67-73

[16] Martin and Elizabeth Devon, Guided Tour and Brief History of St Thomas à Becket Church, Box, 1984, p.5

[17] This section is indebted to Ronald Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England, 1994, OUP, p.7-47

[18] Parish Magazine, July 1929

[19] Ronald Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England, p.28

[20] John Aubrey, The Natural History of Wiltshire, 1656 and 1691, David & Charles Reprint, 1969

[21] Ronald Hutton, The Rise and Fall of Merry England, p.36