|

Roman Pottery, Artefacts &

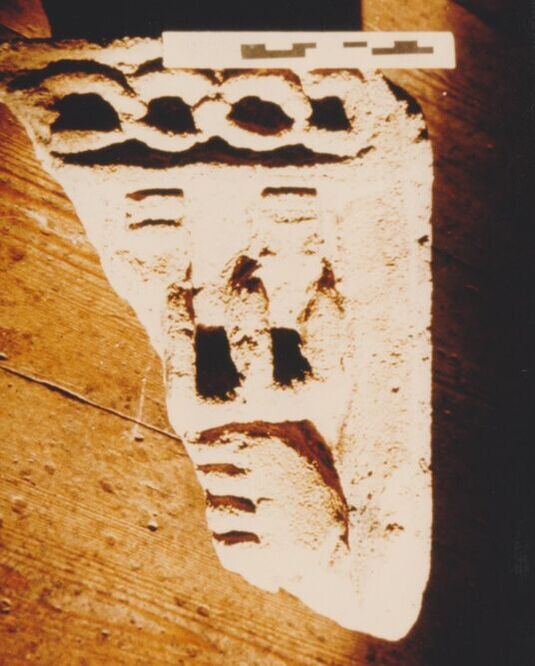

Other Local Finds Research and photographs Kate Carless November 2020 There have been many finds of Roman artefacts in the village. They pop up as isolated anomalies showing the Roman occupation of the area but not indicating their purpose or the extent of the villa site. Tesserae are constantly being unearthed in Box, on the Rec and in the area adjacent to the villa. In the centre finds have been made from the A4 down to Box House and across to The Wilderness, considered to be too large an area to be a single building complex. Finds at the Villa Site Box Roman Villa isn’t Chedworth (it’s much larger) nor Vindolanda (it isn’t a fort). It has only a few finds, such as the statue left, part of a relief-carved panel which was found of a hunter god dressed in a tunic and cloak carrying an unidentified animal over one shoulder and a boar over the other.[1] It reflects the wealth and interests of the building’s owner, dates to the second century and was found in made ground from the later building.[2] Because hunting was reserved to the upper class in Roman society, this sculpture puts the Box villa into an elite status comparable to the Hunter God at Chedworth villa. |

However, the finds discovered are most intriguing, albeit unexplained. The artefact below right shows a hand holding a trident, part of a statue of the Roman god Neptune, who ruled water springs and the seas, whilst his brothers Jupiter and Pluto controlled heaven and the underworld.

|

Wall Plaster

It may be that some artefacts have been lost by inappropriate excavation. In 1892 the Rev EH Goddard reported that painted wall plaster was in great abundance and of a great variety of colours.[3] The thickness of the plaster was 2 or 2½ inches and the general scheme of decoration was that of large panels of colour, bordered and framed by lines of red, green, and white. He also refers to the number of rooms with decoration copying a marble appearance: a wonderful variety of imitations of marble. In Devizes museum, there is a little piece of plaster showing a girl’s head which was found in Box. |

Hypocaust Pillars

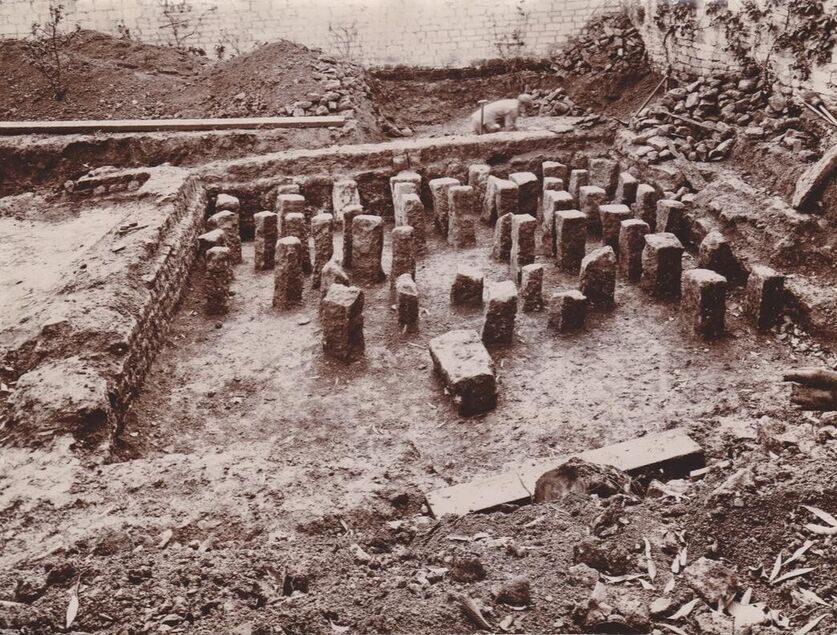

Parts of the villa building were found to be largely complete. Several hypocausts were almost untouched with pillars still standing and evidence of the stoke holes constructed with tiles.[4] These include Rooms 5 and 7.

Parts of the villa building were found to be largely complete. Several hypocausts were almost untouched with pillars still standing and evidence of the stoke holes constructed with tiles.[4] These include Rooms 5 and 7.

Some of the pillars were rough-hewn, such as those in Chamber 10, below left, whilst other stones appeared to have inscriptions, such as the altar below right, again with the hunter-god image which could possibly have come from an earlier building.

Above: Supporting pillars found in the excavations

Nearby Finds in Central Box

One of the intriguing factors in Box is the number of finds in areas surrounding the villa complex. By far the largest collection of finds was found in 1982 at the wall of The Hermitage adjacent to the A4 road. It is reasonably close to the Roman villa site but 100 metres to the south-west and likely to be independent of the villa itself. The finds here are entirely different to other local discoveries, no mosaics, instead up-market tableware and expensive jewellery.

One of the intriguing factors in Box is the number of finds in areas surrounding the villa complex. By far the largest collection of finds was found in 1982 at the wall of The Hermitage adjacent to the A4 road. It is reasonably close to the Roman villa site but 100 metres to the south-west and likely to be independent of the villa itself. The finds here are entirely different to other local discoveries, no mosaics, instead up-market tableware and expensive jewellery.

|

In the summer of 1982 Maurice Hewlett of Hermitage House was digging in his garden to make foundations for a compost heap, when he struck upon rubbish of a much earlier date containing quantities of pottery sherds. A trench was dug across the find-spot which revealed a shallow Roman rubbish-filled ditch. The huge number of finds are especially interesting in that the sherds were in a beautiful and unabraded (not worn away) condition. The ditch was excavated with advice and help from the Devizes Museum. In total 90 kilos of Roman material were recovered, over half of which were pottery sherds in a remarkable state of preservation with edges as sharp as if they had been broken yesterday. They included 49 kilos of pottery mostly grey and black kitchen ware and Samian ware, an amount of glass, and domestic refuse including oyster shells, mussel shells and animal bones and teeth.

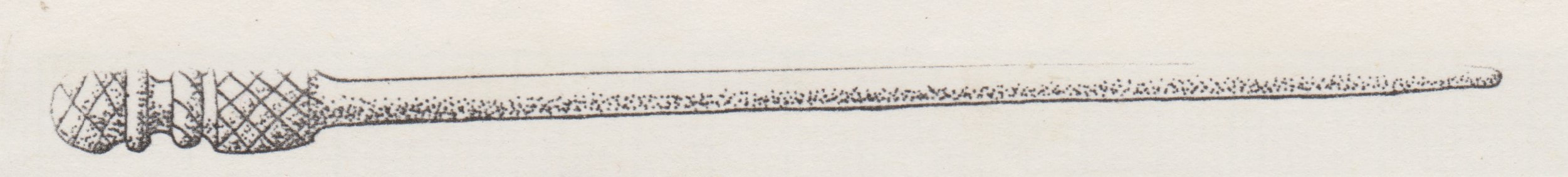

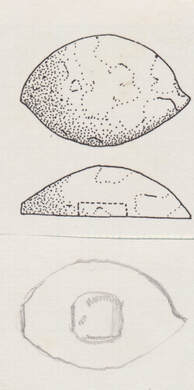

Left: A bone counter found in 1982-83 at The Hermitage |

A variety of metal objects was uncovered in the trench including a life-sized eye in solid silver. This might possibly be from a statue or perhaps it could have been a votive offering (gift deposited in sacred place). The dating of other finds makes for an intriguing supposition that there was an earlier Roman building on or near the site. One theory is that Box may have been a healing spa set between the confluence of two powerful springs and supported by the assertion from John Aubrey that Box had a Holy Well.[5]

The glass finds included a colourless glass ring twisted with yellow decoration.[6] The technique used for making this type of ring involved spinning a glass bead to produce a ring shape. The yellow composition of the glass was found to be similar to that manufactured in pre-Roman times at Meare Lake Village, Somerset, between 500 and 200 BC, except that the addition of manganese oxide into the object put it into the later part of that period. It has been suggested that an earlier glass bead had been reworked between the second century BC and the first century AD. It may have been a child’s betrothal ring as it is too small to fit on a modern finger. Other glass pieces included two long-necked conical jugs, one yellow-brown and the other blue-grey. Both are dated from about AD 65 to AD 125.

Pottery Finds in the Hermitage Ditch

About half a large bowl was found in pieces, which had been mended in antiquity by several rivets. The figure-types shown include Diana and a hind and slaves with baskets. Also found were several drinking cups with name-stamps INDERCLLV(SF), ROPPVSFE and PATERCLI, a potter. The Samian ware dates from about AD 150, probably from mid-France. This piece belonged to a restricted period of time mainly Trajanic to Hadrianic (AD 53 to AD 138). Several pieces of amphora were found, including a rim fragment of a south Spanish amphora. The number of individual pieces was substantial and analysis indicated that the majority was from Poole and others locally made and mass produced. The other table ware was very well made and very well finished.

The bone finds were mostly of obvious food waste and showed unmistakable signs of butchery and of having been cooked. In total 646 bone pieces were found, the majority being of cattle, sheep and pig, with just a few horse, red deer and chicken. The red deer antler pieces had their tines sawn off, almost certainly intended for use as knife handles.

Other Nearby Finds

When Frank Hughes lived in The Wilderness, he assembled an amazing collection of archaeology from the area, including a small bell. More mosaic tiles were uncovered by workmen when building the porch at The Wilderness. One curious find in 1980 was a very large drain dated to the Roman period at the north of Box House and a wall foundation and pottery were found at the Bowling Green opposite Selwyn Hall.

Pottery Finds in the Hermitage Ditch

About half a large bowl was found in pieces, which had been mended in antiquity by several rivets. The figure-types shown include Diana and a hind and slaves with baskets. Also found were several drinking cups with name-stamps INDERCLLV(SF), ROPPVSFE and PATERCLI, a potter. The Samian ware dates from about AD 150, probably from mid-France. This piece belonged to a restricted period of time mainly Trajanic to Hadrianic (AD 53 to AD 138). Several pieces of amphora were found, including a rim fragment of a south Spanish amphora. The number of individual pieces was substantial and analysis indicated that the majority was from Poole and others locally made and mass produced. The other table ware was very well made and very well finished.

The bone finds were mostly of obvious food waste and showed unmistakable signs of butchery and of having been cooked. In total 646 bone pieces were found, the majority being of cattle, sheep and pig, with just a few horse, red deer and chicken. The red deer antler pieces had their tines sawn off, almost certainly intended for use as knife handles.

Other Nearby Finds

When Frank Hughes lived in The Wilderness, he assembled an amazing collection of archaeology from the area, including a small bell. More mosaic tiles were uncovered by workmen when building the porch at The Wilderness. One curious find in 1980 was a very large drain dated to the Roman period at the north of Box House and a wall foundation and pottery were found at the Bowling Green opposite Selwyn Hall.

Several finds have been listed on the Wiltshire Historic Environment Record under the Monument Record search, These include pottery fragments and a belt fitting south and east of Wormwood Farm, finds south of Stowell Wood; a Romano-British stone head at Sunny View Cottage, Henley Lane; and pottery fragments at Totney Hill. And, of course, fragments of mosaics continue to be found in the By Brook at places close to the villa site.[7]

|

Hazelbury Finds

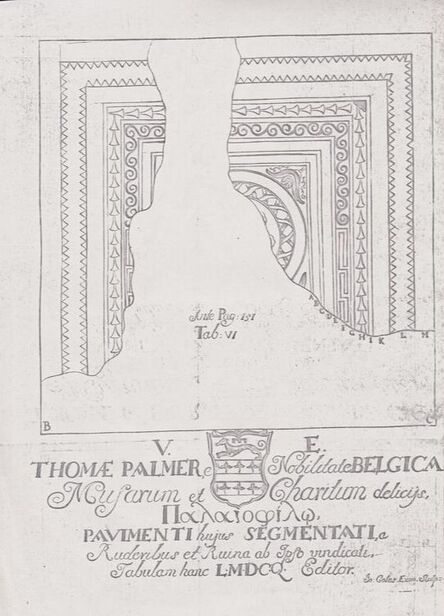

At this point we have to review another local mosaic said to have been found at Hazelbury Manor. It was uncovered in about 1710 by Dr William Musgrave, brother-in-law of Dame Rachel Speke who owned Hazelbury Manor at the time and with whom he used to stay. He wrote a book in 1719 in which he recorded that a pavement was found prope fundum Hasilburiensem (perhaps meaning near Hazelbury Farm). Musgrave arranged for his friend, Thomas Palmer, to make a drawing of it with measurements (right). Of the villa, he said, the basis of the whole construction can be seen today (1719) though not in its entirety, to have stretched to 184 feet in length. It is quite clear that this house was once a magnificent building ...[8] The Hazelbury mosaic can be placed in the fourth century on stylistic grounds. The destroyed central panel almost certainly contained a mythological scene, a bust or, at the very least, a cantharus (sea snail). The lotus flowers occupying two of the surviving corners only occur in this way on two other local mosaics, at Littlecote, Wiltshire, and Weymouth House, Bath. Littlecote has now been dated to AD 360. The mosaic has been deemed to represent everlasting life, perhaps a religious symbol. Right: Illustration of the Hazelbury mosaic |

Musgrave was a grandiose type of man and his book, Antiquitates Britanno Belgicae in 1719, sets out to prove that he and his neighbouring squires were descended from Belgic tribes. He wrote in the rather pompous pseudo-classical Latin that was fashionable for such productions and he does not identify the location of the mosaic apart from vague generalities.

There is considerable circumstantial evidence that Musgrave's mosaic may have come from the Box Villa. No trace of the Hazelbury Villa mosaic has been found by subsequent owners of Hazelbury Manor, including the extensive investigations of

GJ Kidston, apart from a scatter of stone and roofing tiles south of the Manor.[9] The colour scheme of the tesserae, the size of the pavement and the amount of alteration work at the mill of the Wilderness, all fit the Box villa location. The traditional view is that aerial photographs exist showing a large villa at Hazelbury (never found) and the pavement itself existed until a few years ago when it was destroyed. But I cannot discover any evidence of this and I feel that there may be some confusion over the bath house floors or Mr Falconer's lost fragments of Rooms 4 and 8. If Musgrave had found the mosaic at Hazelbury Manor then, surely, he would have said so.

I believe that the Hazelbury mosaic may have originally been the missing apsidal mosaic. The Hazelbury mosaic, 21 feet square and of fourth century appearance, would fit into the apsidal room at Box. Brakspear did find in Room 10 some pieces which apparently were part of a guilloche pattern and some coarse chocolate coloured border. If the entrance to this room was through passage 9 the colour of the border would match the squares on the floor of the passage. Until more evidence is found to the contrary, I feel it is possible to include the Hazelbury mosaic as a floor that could belong to the Box Roman Villa.

There is considerable circumstantial evidence that Musgrave's mosaic may have come from the Box Villa. No trace of the Hazelbury Villa mosaic has been found by subsequent owners of Hazelbury Manor, including the extensive investigations of

GJ Kidston, apart from a scatter of stone and roofing tiles south of the Manor.[9] The colour scheme of the tesserae, the size of the pavement and the amount of alteration work at the mill of the Wilderness, all fit the Box villa location. The traditional view is that aerial photographs exist showing a large villa at Hazelbury (never found) and the pavement itself existed until a few years ago when it was destroyed. But I cannot discover any evidence of this and I feel that there may be some confusion over the bath house floors or Mr Falconer's lost fragments of Rooms 4 and 8. If Musgrave had found the mosaic at Hazelbury Manor then, surely, he would have said so.

I believe that the Hazelbury mosaic may have originally been the missing apsidal mosaic. The Hazelbury mosaic, 21 feet square and of fourth century appearance, would fit into the apsidal room at Box. Brakspear did find in Room 10 some pieces which apparently were part of a guilloche pattern and some coarse chocolate coloured border. If the entrance to this room was through passage 9 the colour of the border would match the squares on the floor of the passage. Until more evidence is found to the contrary, I feel it is possible to include the Hazelbury mosaic as a floor that could belong to the Box Roman Villa.

|

At Hazelbury a coin of Tetricus II (AD 270-272) was found by GJ Kidston in the Manor House in a small square chamber under the oriel window in the hall when the manor was being restored in 1922.[10] Other local finds which have been recorded a heavy iron-tanged plough share.[11] Of course, the report by Richard Musgrave in 1713 is the most significant evidence of Roman remains at Hazelbury, along with crop marks indicating a building which has never been excavated or dated.[12]

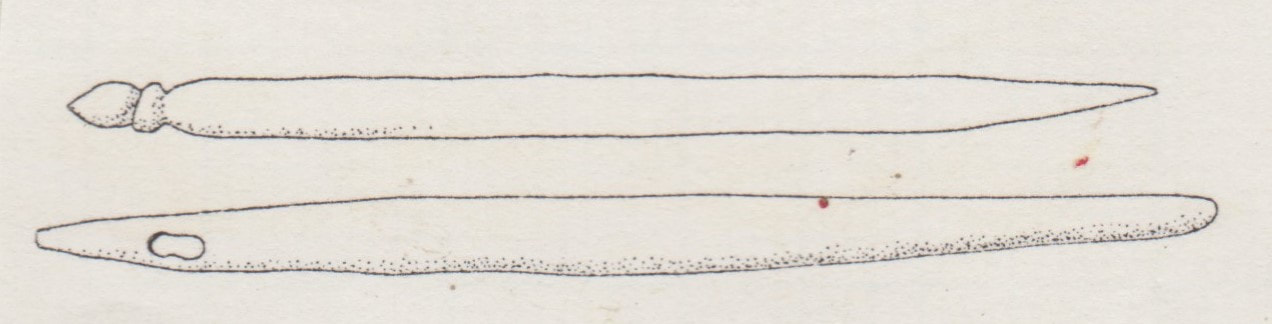

At Alcombe a black, oval glass counter was discovered (left) and a blue glass bead. |

Cheney Court and Ditteridge

In 1813 the remains of a villa were found in the old orchards of Cheney Court, uncovering coins and artefacts.[13] Splinters of Samian ware have been found at Ditteridge.[14] They cover much of the hamlet, north of St Christopher’s Church, north-east of Cheney Court Farm.

In 1813 the remains of a villa were found in the old orchards of Cheney Court, uncovering coins and artefacts.[13] Splinters of Samian ware have been found at Ditteridge.[14] They cover much of the hamlet, north of St Christopher’s Church, north-east of Cheney Court Farm.

References

[1] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol 1 Part 2, Editor RB Pugh, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.453

[2] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.29

[3] Harold Brakspear, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.263

[4] Harold Brakspear, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.247

[5] John Aubrey, The Natural History of Wiltshire, edited John Britton, David & Charles Reprint, 1969 and John Aubrey, Wiltshire - Topographical Collections, edited Canon Jackson, The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 1862

[6] Jenny Price with research from Julian Henderson, Oxford University research laboratory for Archaeology and History of Art

[7] See Early History Hoard

[8] Dr William Musgrave, Antiquitates Britanno, 1719

[9] See Bath Chronicle and Herald, 16 October 1926 for details of the 80 archaeologists assembled by Kidston at Hazelbury

[10] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 16 October 19

[11] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol 1 Part 2, Editor RB Pugh, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.450

[12] R Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.33

[13] Rev John Ayers, One Bell Sounding: A brief history of Ditteridge and its church, 1992

[14] Richard Hodges, www.archaeology.co.uk, April 2013, p.42

[1] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol 1 Part 2, Editor RB Pugh, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.453

[2] HR Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.29

[3] Harold Brakspear, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.263

[4] Harold Brakspear, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Vol XXXIII, 1904, p.247

[5] John Aubrey, The Natural History of Wiltshire, edited John Britton, David & Charles Reprint, 1969 and John Aubrey, Wiltshire - Topographical Collections, edited Canon Jackson, The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 1862

[6] Jenny Price with research from Julian Henderson, Oxford University research laboratory for Archaeology and History of Art

[7] See Early History Hoard

[8] Dr William Musgrave, Antiquitates Britanno, 1719

[9] See Bath Chronicle and Herald, 16 October 1926 for details of the 80 archaeologists assembled by Kidston at Hazelbury

[10] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 16 October 19

[11] Victoria County History of Wiltshire, Vol 1 Part 2, Editor RB Pugh, 1973, Oxford University Press, p.450

[12] R Hurst, DL Dartnall and C Fisher, Excavations at Box Roman Villa 1967-68, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine, Vol.81, 1987, p.33

[13] Rev John Ayers, One Bell Sounding: A brief history of Ditteridge and its church, 1992

[14] Richard Hodges, www.archaeology.co.uk, April 2013, p.42