|

Lambert's Stoneyard

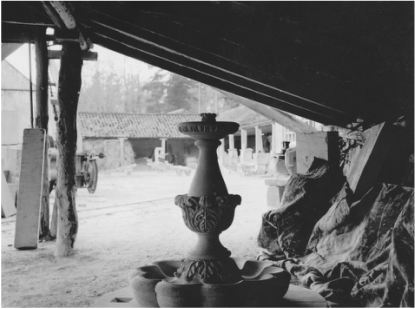

Research and photographs by Margaret Wakefield and Anna Grayson February 2017 The activity in Box's stoneyards was quite different to the extraction of stone from the quarries. Whilst the quarrymen hewed massive blocks of raw stone from below the ground, stonemasons in the yards fashioned it into material for the construction of buildings, some of it of great intricacy and sculptural in design. It was a processing of raw material similar, in some ways, to the manufacture of iron and steel products from raw ore. The stoneyard industry dominated Box and was highly visible because the village was full of stacks of stone weathering to harden the stone. The stone dust caused by sawing into blocks and the carving of stone deposited powder throughout the area. A Bath schoolgirl, Elsie Sealy, wrote about the importance of the stoneyards in her childhood in the late 1800s, saying Box Station siding was full of its whiteness.[1] Right: TH Lambert's sculptural work in Winchester Cathedral was the most important piece, the image of Christ on the Cross on the Great Screen. |

Box Station Yard Before the Lamberts

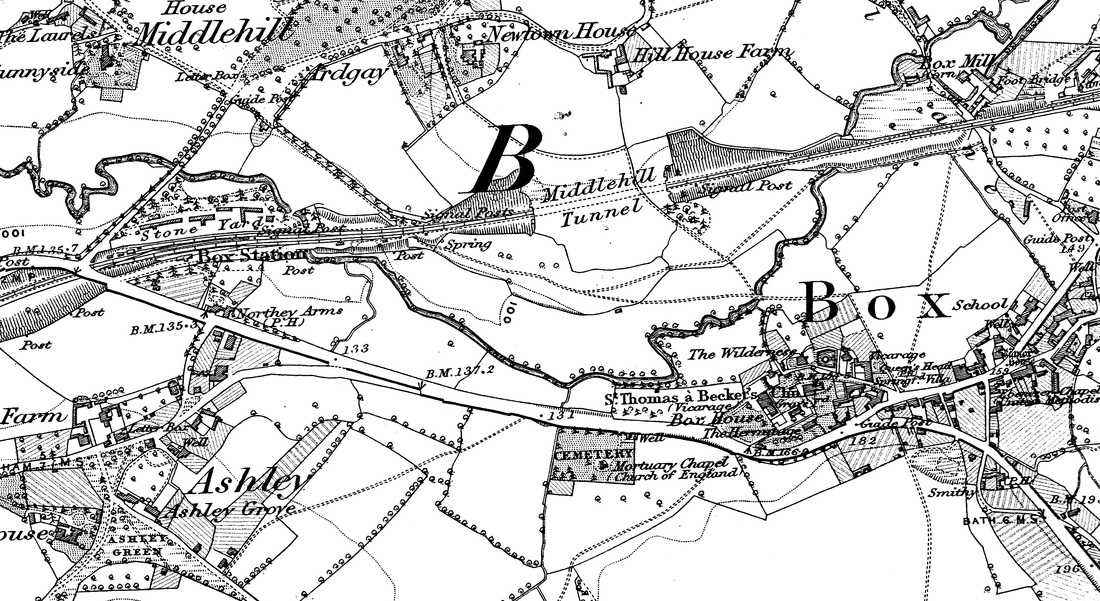

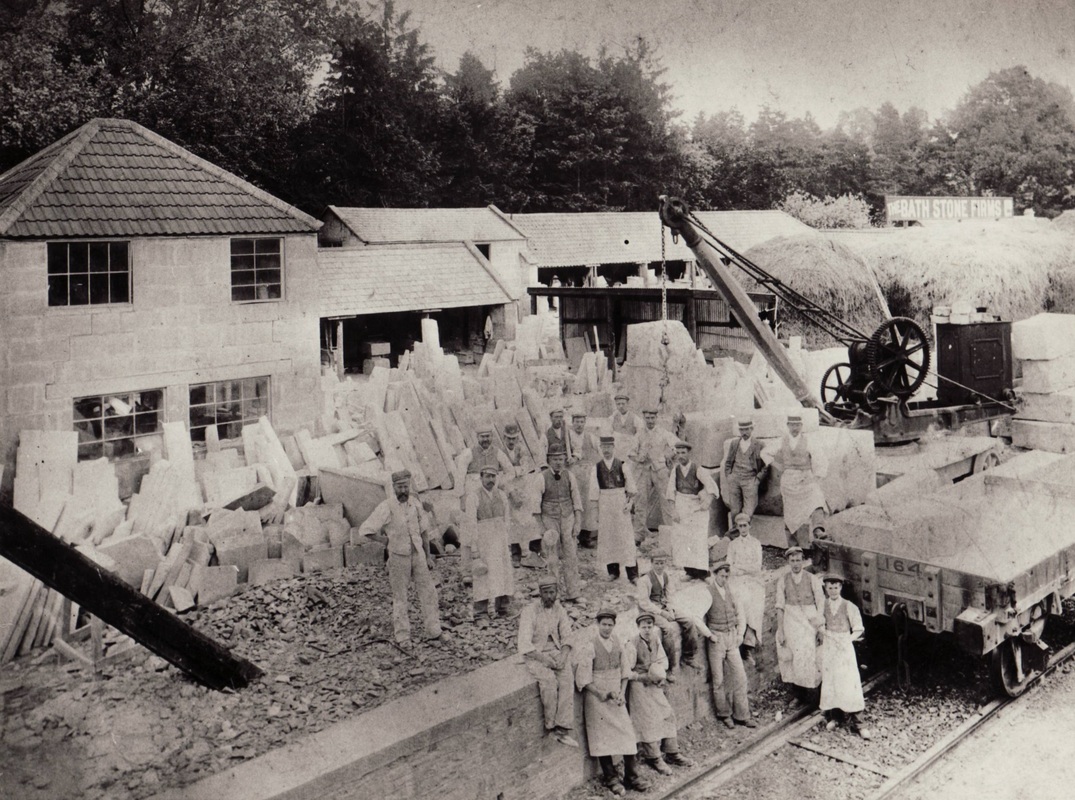

The stoneyards on the north side of the railway station were developed between 1845 and 1850, when the Great Western Railway (GRW) extended the wharf for loading of stone into trucks at the Box Station.[2] The yards there were convenient for railway access and GWR built cranes to move stone blocks onto the rail trucks. Several firms developed stoneyards on the site, each of which required access from their part of the yards onto the rail line with separate sidings criss-crossing the area.

Mr Stone's yard was given separate sidings to connect to both the up and down lines in the 1860s.[3]

The stoneyards on the north side of the railway station were developed between 1845 and 1850, when the Great Western Railway (GRW) extended the wharf for loading of stone into trucks at the Box Station.[2] The yards there were convenient for railway access and GWR built cranes to move stone blocks onto the rail trucks. Several firms developed stoneyards on the site, each of which required access from their part of the yards onto the rail line with separate sidings criss-crossing the area.

Mr Stone's yard was given separate sidings to connect to both the up and down lines in the 1860s.[3]

Above: Lamberts Yard with cranes and railway sidings. The masons area was open to the elements.

Box Station stoneyards developed from a wharf built there between 1840 and 1845 by the Great Western Railway Company.[4]

In 1887 the industry was in deep depression and five firms at Box Station stoneyard amalgamated to form the Bath Stone Firms Limited (BSFL). At that time five firms were working out of the Box Station stoneyard: Stone Brothers Limited, RJ Marsh & Co Ltd, Randell and Saunders Ltd, The Corsham Bath Stone Company Limited and Isaac Sumsion.[5]

In so doing, there were opportunities for smaller firms to evolve, run by individual masons, often subcontracting to BSFL, from whom they bought the raw stone blocks on credit. One such example was two members of the same family called William Smith, comprising father (born 1791) and son (1830 - 1895). The family had worked on Box Tunnel and in 1841 were recorded as living at Box Tunnel Shaft number 2. William Smith the son lived in the centre of Box at The Parade and was always described as a mason. On his death in 1895, his business was sold to thirty-five year old Thomas Herbert (often called TH) Lambert.

In 1887 the industry was in deep depression and five firms at Box Station stoneyard amalgamated to form the Bath Stone Firms Limited (BSFL). At that time five firms were working out of the Box Station stoneyard: Stone Brothers Limited, RJ Marsh & Co Ltd, Randell and Saunders Ltd, The Corsham Bath Stone Company Limited and Isaac Sumsion.[5]

In so doing, there were opportunities for smaller firms to evolve, run by individual masons, often subcontracting to BSFL, from whom they bought the raw stone blocks on credit. One such example was two members of the same family called William Smith, comprising father (born 1791) and son (1830 - 1895). The family had worked on Box Tunnel and in 1841 were recorded as living at Box Tunnel Shaft number 2. William Smith the son lived in the centre of Box at The Parade and was always described as a mason. On his death in 1895, his business was sold to thirty-five year old Thomas Herbert (often called TH) Lambert.

Thomas Herbert Lambert

There is an intriguing reference in 1861, the year after Thomas Herbert's birth, to a dinner at the Northey Arms, to commemorate that Box masons declined to join a London quarryman's strike.[6] Mr Lambert was agent (manager) to Mr Meyers ... one of the principal employers. Mr Lambert had worked for Meyers upwards of fourteen years. Masonry was a family tradition which had brought the family to Box in the first place. The Lambert mentioned in the article may be Henry, Thomas Herbert's father, but more probably was Isaac Lambert of Ashley, with whom Henry worked for many years. I'm almost certain that they were related though I have not establish the link.

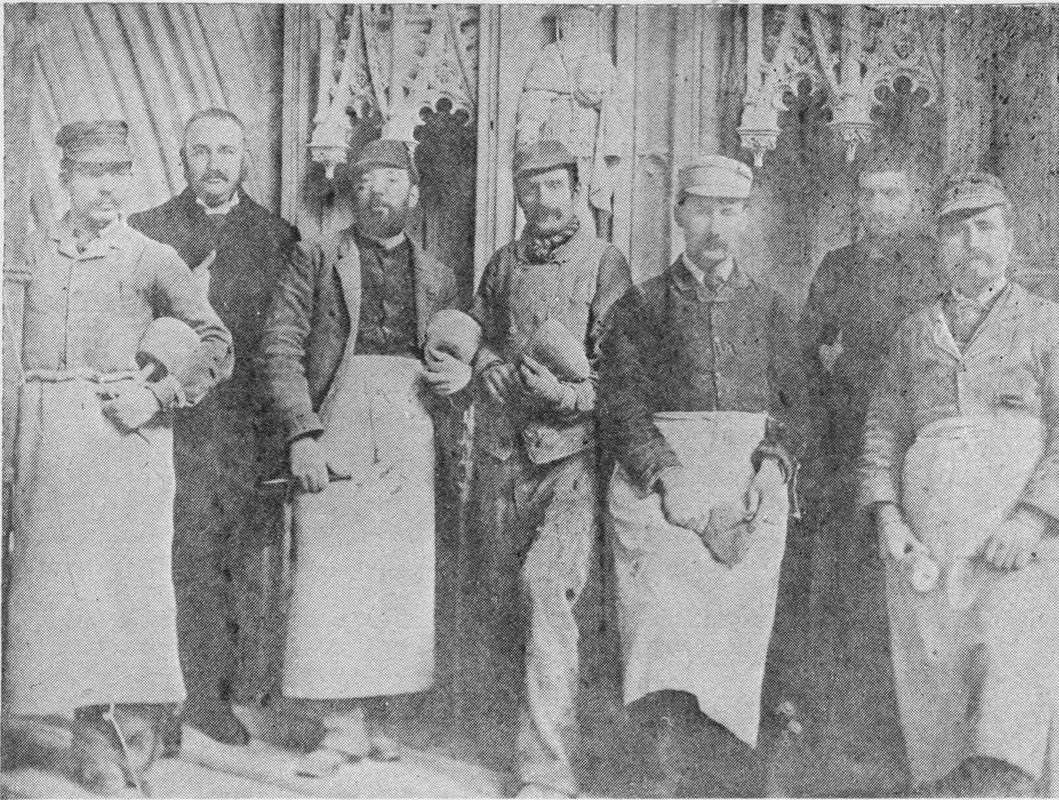

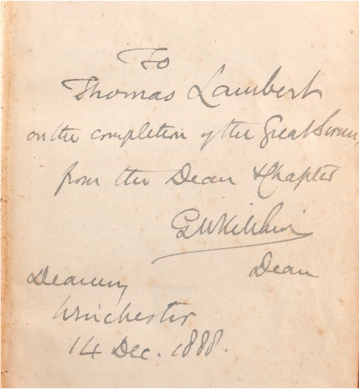

Thomas Herbert Lambert was a highly-skilled mason. He completed the figure in the heading photo of Christ on the Cross on the Great Screen of Winchester Cathedral. He was probably working as a journeyman mason (working at the client's premises) on his own, and it was the foundation of his reputation for skill and precision.[7] It was a most difficult piece of work. The screen had been in a poor condition, bare and desolate and there were many obstacles, fundraising concerns, conflicting plans, protests in 1885 and 1886. The most important sculpture, Christ on the Cross, remained unfinished until TH became involved and completed the work in its magnificent final presentation.

There is an intriguing reference in 1861, the year after Thomas Herbert's birth, to a dinner at the Northey Arms, to commemorate that Box masons declined to join a London quarryman's strike.[6] Mr Lambert was agent (manager) to Mr Meyers ... one of the principal employers. Mr Lambert had worked for Meyers upwards of fourteen years. Masonry was a family tradition which had brought the family to Box in the first place. The Lambert mentioned in the article may be Henry, Thomas Herbert's father, but more probably was Isaac Lambert of Ashley, with whom Henry worked for many years. I'm almost certain that they were related though I have not establish the link.

Thomas Herbert Lambert was a highly-skilled mason. He completed the figure in the heading photo of Christ on the Cross on the Great Screen of Winchester Cathedral. He was probably working as a journeyman mason (working at the client's premises) on his own, and it was the foundation of his reputation for skill and precision.[7] It was a most difficult piece of work. The screen had been in a poor condition, bare and desolate and there were many obstacles, fundraising concerns, conflicting plans, protests in 1885 and 1886. The most important sculpture, Christ on the Cross, remained unfinished until TH became involved and completed the work in its magnificent final presentation.

Above Left: TH Lambert, third right; and Above Right, the Bible given to him on completion of the Winchester work in 1888.

Lambert's Yard

He was appointed masonry manager for the Northey Stone Company (possibly working at Longsplatt) and in 1895 he started working alongside the Bath & Portland Stone Firms Limited.[8] In that year he launched out by forming his own stoneyard and he paid £65.19s for the stock-in-trade of the late William Smith on 12 October 1895. It may be that William had outstanding debts owed to The Bath Stone Firms Limited for stone bought from them because the deal was completed by BSFL's general manager, George Hancock, at our eastern-most mason's yard and sheds at Box station.[9] In addition TH bought quantities of Box Ashlar and Farleigh stone to start his business.

It was under TH's control that the stoneyard expanded rapidly undertaking a number of highly skilled jobs throughout Britain.

The firm became a family business and TH appears to be trading with his brother Alfred because in 1904 new offices built by

T Merrett & Son were invoiced to Lambert Bros.[10] We might speculate that Alfred separated from the business in January 1906 to start his own stoneyard at Corsham Railway Station because TH had a new stock valuation prepared at that time. Between 1901 and 1907 he built Kingston Villas on the London Road, where he lived with his family in number 2 Kingston Villas.[11]

Throughout the time of the yard, even in the worst years, the firm made regular weekly donations to the Royal United Hospital, Bath, on behalf of the staff and employers. As well as his business interests, TH was well-known in Box for his social and political work.[12] He was elected onto the first civil Box Parish Council of 1894, on which he served for 40 years, and he also served as a Box Parish Overseer and on the Board of Guardians. He was described as a Radical in politics being chairman of the local Liberal Association for many years. He found time to be the honorary secretary of the local Oddfellows Association, who organised the first Box horticultural exhibition in 1891.[13] As honorary treasurer of the Box Carnival and Fete held in August 1921, he was instrumental in raising funds for the war memorial.[14] And, of course, he was the longest serving member of Box Cricket Club.

He was appointed masonry manager for the Northey Stone Company (possibly working at Longsplatt) and in 1895 he started working alongside the Bath & Portland Stone Firms Limited.[8] In that year he launched out by forming his own stoneyard and he paid £65.19s for the stock-in-trade of the late William Smith on 12 October 1895. It may be that William had outstanding debts owed to The Bath Stone Firms Limited for stone bought from them because the deal was completed by BSFL's general manager, George Hancock, at our eastern-most mason's yard and sheds at Box station.[9] In addition TH bought quantities of Box Ashlar and Farleigh stone to start his business.

It was under TH's control that the stoneyard expanded rapidly undertaking a number of highly skilled jobs throughout Britain.

The firm became a family business and TH appears to be trading with his brother Alfred because in 1904 new offices built by

T Merrett & Son were invoiced to Lambert Bros.[10] We might speculate that Alfred separated from the business in January 1906 to start his own stoneyard at Corsham Railway Station because TH had a new stock valuation prepared at that time. Between 1901 and 1907 he built Kingston Villas on the London Road, where he lived with his family in number 2 Kingston Villas.[11]

Throughout the time of the yard, even in the worst years, the firm made regular weekly donations to the Royal United Hospital, Bath, on behalf of the staff and employers. As well as his business interests, TH was well-known in Box for his social and political work.[12] He was elected onto the first civil Box Parish Council of 1894, on which he served for 40 years, and he also served as a Box Parish Overseer and on the Board of Guardians. He was described as a Radical in politics being chairman of the local Liberal Association for many years. He found time to be the honorary secretary of the local Oddfellows Association, who organised the first Box horticultural exhibition in 1891.[13] As honorary treasurer of the Box Carnival and Fete held in August 1921, he was instrumental in raising funds for the war memorial.[14] And, of course, he was the longest serving member of Box Cricket Club.

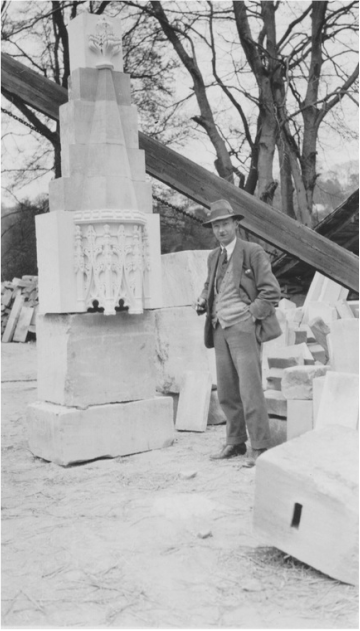

TH Lambert and Son, Cecil

In January 1928 TH was joined in partnership by his son, Cecil, aged 34, a war veteran and architect. It was a period of great success for The Bath & Portland Stone Forms Limited who achieved record dividends and bonuses equal to 20 per cent in 1926 and record net profits of £57,804 in 1927.[15] We might imagine that the stoneyards were enjoying similar successes at this time.

In January 1928 TH was joined in partnership by his son, Cecil, aged 34, a war veteran and architect. It was a period of great success for The Bath & Portland Stone Forms Limited who achieved record dividends and bonuses equal to 20 per cent in 1926 and record net profits of £57,804 in 1927.[15] We might imagine that the stoneyards were enjoying similar successes at this time.

|

By then the business was considerably larger than that bought by TH in 1895. The valuation in 1928 amounted to £426.13s.8d, comprising: Office Contents £64.6s.4d, Plant in Sawing Tent, Masons' Shop, Mess Room and Lathe House £79.13s.0d, Stone Blocks £143.5s.7d, Worked Stone, Cut Stone and Cut Slab £80.16s.0d, Wall Stone £49.8s.9d, Bankers & Tops £4.4s.0d and Sand £5.0s.0d.[16]

During the 1920s the business supplied materials for buildings throughout Britain including shop fronts in Exmouth, Oakhampton Midland Bank and a Wesleyan Church at Kidsgrove. The work was prestigious, referred by architects and large builders.[17] The most notable prestigious commissions included a ladies lavatory at Victoria Station, London, the Prudential Buildings at High Holborn, London, a massive factory for Aladdin Industries of Greenford, makers of paraffin lamps and heaters, and Bournemouth Town Hall. Inside three years they had worked 42,000 cubic feet of stone at a price approaching 6s per cubic foot. One of the most important jobs undertaken by the yard was the building of Downside Abbey Church in 1925. The firm was immensely proud of its work and produced pamphlets and postcards of significant jobs, which will be produced in a later article. |

Part of the success of the stoneyard industries came from the concentration of the trade amongst particular families connected by marriage. They developed individual skills and sometimes exchanged work. Charles Richards of Thornwood, Devizes Road, was a mason who ran his own stoneyard business and the Greenford work referred to above was carried out by the Lamberts in association with Richards and Milsom. The two families were related, Thomas Herbert Lambert's second wife, Beatrice Annie Lambert, was the daughter of Charles and Emma Amelia Richards. Frank Hobbs, part of an old Box quarrying family, who had valued the 1895 stock, was Beatrice's uncle because Charles Richards had married Emma Amelia Hobbs, maid of the Horlock family. The Norkett family were related to the Lamberts when Henry John (Jack) Norkett of Ditteridge married Georgina Mildred Lambert in 1925.[18]

|

End of Lambert's Yard

The stone trade was decimated in the 1930s. National import duties started in USA in 1930 as a reaction to the Wall Street Crash and were followed by the British Import Duties Act of 1932. This was succeeded by a worldwide economic depression and the lead up to the Second World War. The accounts for Lambert's Yard make uncomfortable reading.[19] Jobs were recorded as Price no good, Original estimate not good enough, Job did not pay through excess of labour.[20] The price of a cubic ton of stone fell to about 5s 6d for many jobs and volumes slumped. |

The firm supplied numerous fireplace surrounds, some gravestones and even started recording the sale of bags of stone dust, used as a fire-suppressant in the Somerset coal fields.[21] Where previous prestige jobs had involved 6,000 cubic feet of worked stone, pre-designed fireplaces were only 8 cubic feet and one job was recorded as 5 cubic inches.

Most staff were laid off but costs outran income. During 1935 the company was running an adverse balance of about £200; by May 1936 this had increased to £428, only partly alleviated by work for The Royal Russell School, Ballards, Croydon, in 1937. Some work was shared with Alfred Lambert's Corsham yard for three replacement windows at Downside Abbey but these were exceptions to the norm.

In his late seventies in the 1930s TH Lambert gradually withdrew from the business and he died on 24 December 1938. The stoneyard closed for new work in December 1939 and in March 1948 Cecil received £300 from HP (Prosser) Chaffey manager of B&PSFL in settlement of a list made in 1939 of outstanding kit, stock-in-trade when the yard was closed.[22] Cecil offered his services to the Firms but this was declined as the position of Box Station is unsatisfactory. I think it is extremely unlikely that they will reopen as masonry yards.

Most staff were laid off but costs outran income. During 1935 the company was running an adverse balance of about £200; by May 1936 this had increased to £428, only partly alleviated by work for The Royal Russell School, Ballards, Croydon, in 1937. Some work was shared with Alfred Lambert's Corsham yard for three replacement windows at Downside Abbey but these were exceptions to the norm.

In his late seventies in the 1930s TH Lambert gradually withdrew from the business and he died on 24 December 1938. The stoneyard closed for new work in December 1939 and in March 1948 Cecil received £300 from HP (Prosser) Chaffey manager of B&PSFL in settlement of a list made in 1939 of outstanding kit, stock-in-trade when the yard was closed.[22] Cecil offered his services to the Firms but this was declined as the position of Box Station is unsatisfactory. I think it is extremely unlikely that they will reopen as masonry yards.

It must have been a considerable blow to Cecil whose interest in the work had been shown for decades including his First World War letters to his father asking how TH was managing without skilled masons.[23] After the Second World War Cecil was involved in much architectural work on London bomb restoration work including Southwark Cathedral, designing Box's council house estates, work on Murray & Baldwin's premises (the old Box Brewery) and at Hartham Park. But this work was personal and the stoneyard never reopened.

Conclusion

The Lamberts prided themselves on being good employers with charabanc outings and offering continuous employment so far as recessions in the industry allowed. The job of masons was a trade restricted to skilled craftsmen and the industry was fiercely proud of its family traditions. In 1932 thirty-two employees from the yard went to the seaside at Bournemouth for the day.[24]

On his death in 1943, Mr J Hancock of the Ley was recalled as a banker mason, a very efficient craftsman who had been employed by the late Mr Shewring and the late Mr Thomas Lambert, a member of the Masons' Lodge and the Box Parish Church.[25] To young people today, this is a world of continuity now gone forever, destroyed by the wars of the twentieth century.

After World War 2 new materials and cheaper methods of production became available. The heyday of the stoneyards had been short-lived and after the war it ended. Cecil Lambert lived until 1970 and continued the social and public service roles of his father, completing 35 years on Box Parish Council and chairing the Comrades Legion Club for many decades. The Lambert family have left a visible mark on countless buildings in Box village and beyond.

The Lamberts prided themselves on being good employers with charabanc outings and offering continuous employment so far as recessions in the industry allowed. The job of masons was a trade restricted to skilled craftsmen and the industry was fiercely proud of its family traditions. In 1932 thirty-two employees from the yard went to the seaside at Bournemouth for the day.[24]

On his death in 1943, Mr J Hancock of the Ley was recalled as a banker mason, a very efficient craftsman who had been employed by the late Mr Shewring and the late Mr Thomas Lambert, a member of the Masons' Lodge and the Box Parish Church.[25] To young people today, this is a world of continuity now gone forever, destroyed by the wars of the twentieth century.

After World War 2 new materials and cheaper methods of production became available. The heyday of the stoneyards had been short-lived and after the war it ended. Cecil Lambert lived until 1970 and continued the social and public service roles of his father, completing 35 years on Box Parish Council and chairing the Comrades Legion Club for many decades. The Lambert family have left a visible mark on countless buildings in Box village and beyond.

Family Tree

Henry Lambert (b 10 September 1829) married in 1856 to Sarah Jane Kingston (b 1835)

Children all born in Box: George Henry (b 1857); Jane Henrietta (b 1859); Thomas Herbert (16 December 1860 - 21 December 1938); Annie H (b 1864); Lucy (b 1866); Florence Elizabeth (b 1872); Georgina Mildred (b 1874 who married Henry John Norkett); Alfred Kingston (b 1876)

Thomas Herbert Lambert (1860 - 1938) married (a) Malinda Leonora White (13 October 1857 - 15 April 1900) and (b) Beatrice Annie Richards (19 May 1878 - 12 November 1970).

Children: (a) Lucy Florence (b 1892); Herbert (1893 - 1965); Cecil (15 December 1894 - 1970); Edward (b 1897); Francis George White (b 1900)

Children: (b) Kathleen Kingston (b 11 August 1906); Philip Henry (15 June 1908 - December 1991); Enid Margaret (10 June 1911 - October 1999) and Betty.

Henry Lambert (b 10 September 1829) married in 1856 to Sarah Jane Kingston (b 1835)

Children all born in Box: George Henry (b 1857); Jane Henrietta (b 1859); Thomas Herbert (16 December 1860 - 21 December 1938); Annie H (b 1864); Lucy (b 1866); Florence Elizabeth (b 1872); Georgina Mildred (b 1874 who married Henry John Norkett); Alfred Kingston (b 1876)

Thomas Herbert Lambert (1860 - 1938) married (a) Malinda Leonora White (13 October 1857 - 15 April 1900) and (b) Beatrice Annie Richards (19 May 1878 - 12 November 1970).

Children: (a) Lucy Florence (b 1892); Herbert (1893 - 1965); Cecil (15 December 1894 - 1970); Edward (b 1897); Francis George White (b 1900)

Children: (b) Kathleen Kingston (b 11 August 1906); Philip Henry (15 June 1908 - December 1991); Enid Margaret (10 June 1911 - October 1999) and Betty.

References

[1] Elsie B Sealy, My Memoirs, p.4

[2] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[3] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[4] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[5] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[6] We are indebted to David Pollard for this reference to Bath Weekly Chronicle, 24 October 1861. David adds Myers was a national builder, perhaps a Wimpey or McAlpine of his time, he was Pugin’s preferred builder.

[7] Frederick Bussby, Winchester Cathedral Record number 48, 1979, p.12-15

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[9] Valuation 12 October 1895 of the Stoneyard and Effects, property of BSFL, taken by F Hobbs and WR Shewring.

[10] Invoice March 1904

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 8 August 1907

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 6 August 1891

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 6 August 1921

[15] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 24 March 1928

[16] Valuation 30 June 1928 taken by HJ Norkett and J Weeks

[17] Lambert & Son Contracts Book June 1928 - 1939

[18] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 10 October 1925

[19] Lambert & Son Cash Account Book September 1935 - June 1941

[20] Lambert & Son Contracts Book June 1928 - 1939

[21] Derek Hawkins, Bath Stone Quarries, 2011, Folly Books, p.18

[22] Letters dated 5 January 1948, 26 February 1948 and 2 March 1948

[23] See Ypres section in Cecil Lambert's War Diary

[24] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 July 1932

[25] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 April 1943

[1] Elsie B Sealy, My Memoirs, p.4

[2] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[3] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[4] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[5] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.137

[6] We are indebted to David Pollard for this reference to Bath Weekly Chronicle, 24 October 1861. David adds Myers was a national builder, perhaps a Wimpey or McAlpine of his time, he was Pugin’s preferred builder.

[7] Frederick Bussby, Winchester Cathedral Record number 48, 1979, p.12-15

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[9] Valuation 12 October 1895 of the Stoneyard and Effects, property of BSFL, taken by F Hobbs and WR Shewring.

[10] Invoice March 1904

[11] The Bath Chronicle, 8 August 1907

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[13] The Bath Chronicle, 6 August 1891

[14] The Bath Chronicle, 6 August 1921

[15] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 24 March 1928

[16] Valuation 30 June 1928 taken by HJ Norkett and J Weeks

[17] Lambert & Son Contracts Book June 1928 - 1939

[18] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 10 October 1925

[19] Lambert & Son Cash Account Book September 1935 - June 1941

[20] Lambert & Son Contracts Book June 1928 - 1939

[21] Derek Hawkins, Bath Stone Quarries, 2011, Folly Books, p.18

[22] Letters dated 5 January 1948, 26 February 1948 and 2 March 1948

[23] See Ypres section in Cecil Lambert's War Diary

[24] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 July 1932

[25] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 April 1943