Three Kingsdown Cottages: Part 1 Jane Hussey June 2020

|

Few cottages were named in Kingsdown before the 1880s, just referred to by the family occupying them and the address given as Kingsdown. This has made the history of the area difficult to establish, although my family history can help to throw light on some of the properties. They once occupied a row of three cottages which they owned, lived in, let out, fought over and rented. The three cottages face sideways to the road with a garden in front of them and orchard to the lower side of them, but no land at the back.

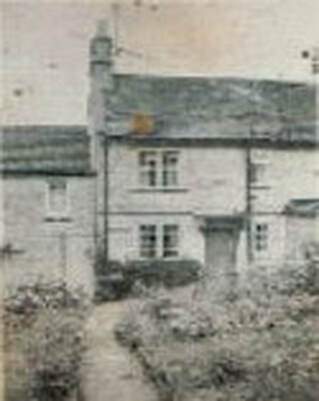

The cottages were sometimes numbered 1 to 3 starting from the Lower Kingsdown Road. At other times they have been named Ash Cottage on the road, then Vine Cottage in the middle and the property at the bottom just called The Cottage (now Wolwehoek). A separate cottage used to exist at the rear of Number 2 called Keeler’s Cottage. Vine Cottage (No 2) and garden on the right in the 1950s with the lower cottage just called The Cottage on the left (courtesy Jane Hussey) |

Origins of the Area

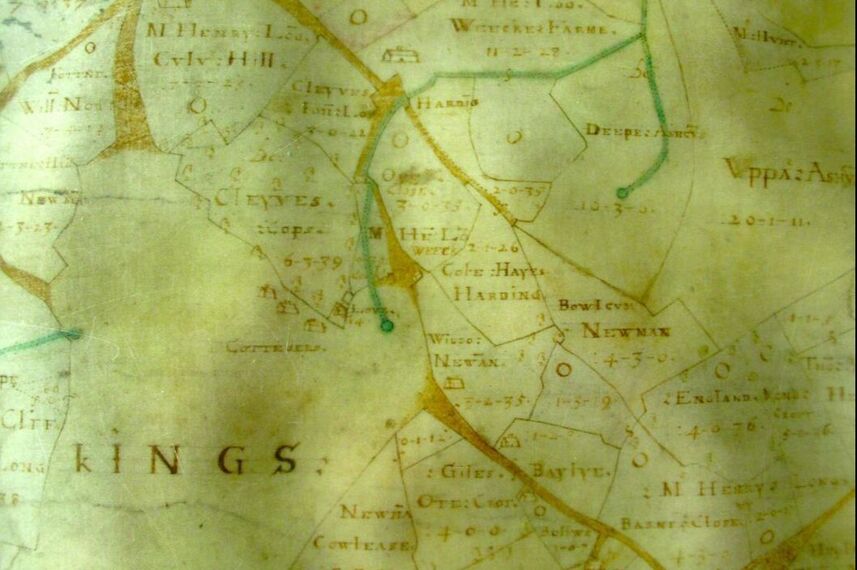

The first buildings in the area are shrouded in uncertainty. The map below is dated 1626 and shows tracks (brown) which approach Kingsdown until they suddenly peter out. Several fields have the name of the occupier as Newman and the 1626 List of Ratepayers identifies the widow Newman who had a tenement (cottage and land) at Kingsdoune worth £10.

The first buildings in the area are shrouded in uncertainty. The map below is dated 1626 and shows tracks (brown) which approach Kingsdown until they suddenly peter out. Several fields have the name of the occupier as Newman and the 1626 List of Ratepayers identifies the widow Newman who had a tenement (cottage and land) at Kingsdoune worth £10.

It is believed that this row of three stone and pantile cottages was built during the reign of Queen Anne, 1701-1713.[1] This is because a small figurehead above the middle cottage door might be of the Queen. The Queen visited Bath in 1702-03 with such a following that the villages for miles around were full of Queen Anne representations. The figurehead could be a total red herring as it is not known whether it was there at the time of building, and could have been a standard moulding purchased from a builder's merchant at a later date and added. The owners of the lower cottage believe that the row was built around 1750. If this is the case it may well have been by our Newman ancestors, though still not proven, as Richard Newman's marriage in 1760 in Box is the first of my proven lineage. There were plenty of Newman masons before him living at Box and Kingsdown but as yet not directly linked to our branch.

The 1839 Record

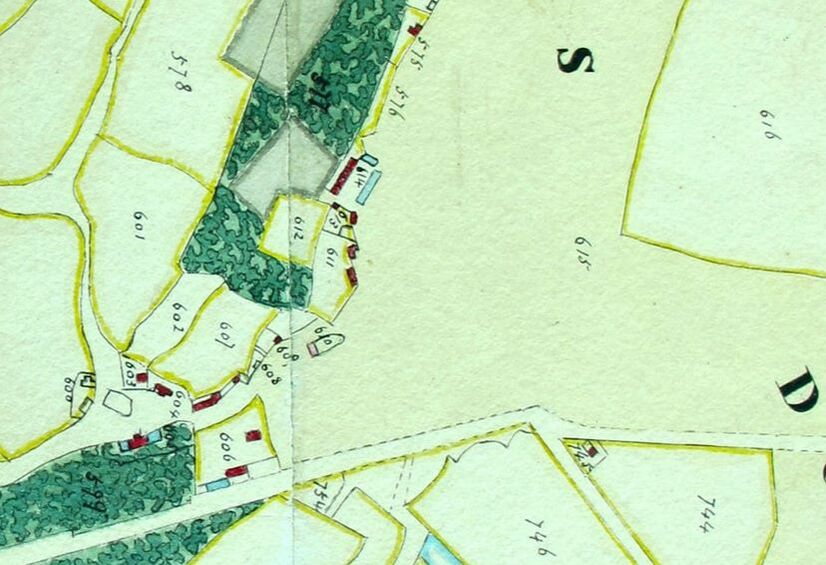

The Kingsdown Cottages are shown on the Box Tithe Map of 1839 as plot 613. The plot was tenanted by Jacob Newman with one cottage occupied by Jacob and the others sublet to John Harris, William White, John Greenaway, Isaac Stephens and James Gale. The whole plot covers a slightly larger area than just the three cottages. It is worth recording the area around this plot as these people recur later in the article. The plot next door 611 was a house, outbuildings and garden, occupied by James Hancock who paid their tithe to the vicar Rev HCDS Horlock; plot 615 is Kingsdown Common and plot 614 was cottages and gardens held by George Salmon and others and appears to be Tyning Cottage.

The three cottages weren’t important, just a small terrace of humble residences for local quarrymen but their story deserves to be told because they played a significant role in shaping the history and fates of their residents and the immediate area.

The Kingsdown Cottages are shown on the Box Tithe Map of 1839 as plot 613. The plot was tenanted by Jacob Newman with one cottage occupied by Jacob and the others sublet to John Harris, William White, John Greenaway, Isaac Stephens and James Gale. The whole plot covers a slightly larger area than just the three cottages. It is worth recording the area around this plot as these people recur later in the article. The plot next door 611 was a house, outbuildings and garden, occupied by James Hancock who paid their tithe to the vicar Rev HCDS Horlock; plot 615 is Kingsdown Common and plot 614 was cottages and gardens held by George Salmon and others and appears to be Tyning Cottage.

The three cottages weren’t important, just a small terrace of humble residences for local quarrymen but their story deserves to be told because they played a significant role in shaping the history and fates of their residents and the immediate area.

It is interesting that these properties started just where the main tracks through the downs came to an end (as in the1626 map) and, of course, the name Newman in 1626 and 1839 is one of my family ancestral names.

The Buildings

The three cottages owned by my family were possibly built at different times. The third cottage is lower in height and has a large garden sloping away down the hill. The long narrow gardens of the top two were at the front of the row with a side wall to the road running around Kingsdown Hill. On the back of these three was a tiny cottage facing in the Box direction. In the 1909 National Land Survey the cottages are classed old and their condition only fair. By the early 1980s not much had changed in the outward appearance of these dwellings but internally quite a bit had altered, as one might expect.

The construction of these cottages is true to Georgian building form with the front façades faced with smooth ashlar on the outside. This was the posh front on view to the public. Ashlar blocks were laid in even courses with almost invisible hairline mortar joints between them to give the wall as even and seamless an appearance as possible and then the entire façade would be combed down with a mason's drag which resembled a large toothed comb to smooth out any blemishes. The remarks by the great Bath architect John Wood on Bath ashlar stone are apt: he confirmed that the free stone used was beyond dispute a most excellent building material, being beautiful, durable and cheap. But he insinuated that, because the blocks were transported ready-wrought to site, the sharp edges and corners of this stone generally broke and the neatness of the joints and sharpness in the edges of the mouldings was lost. The fronts of the Kingsdown cottages are rather like this in quality and with a weathered look gained over the years.

As ashlar was an expensive material, only one depth of this dressed stone on the façade was used and immediately behind it the rougher-looking rubble stone was used. The rubble and ashlar walls were tied together at intervals by the longer bonding stones which projected from the ashlar face into the rubble core. This rubble stone was either cut from the leftover waste from larger blocks, or quarried from other beds in the quarry. The rubble stone would be tightly packed in the same way as in a drystone wall often in courses with copious amounts of lime and mortar filling the crevices and voids and this also helped spread the load. Oyster shells or pieces of slate were used to back the joints, oysters not being the delicacy they are today, but eaten in plenty in previous times.

The fronts of the three cottages have a single decoration of a plat band protruding slightly between the ground and first floor, but the backs of the cottages are just rubble. They had elegant ashlar chimneys each with two moulded narrow bands.

Sash windows for cottages were becoming popular about 1692 and by 1720 had become very fashionable, suiting the symmetry of grand Palladian architecture in towns and cities. They did not rattle like the old casement windows, needed very little maintenance and had the advantage of allowing in more light than the diamond-shaped panes, each sash being square usually with 9 small panes in it. As early as 1701 both sashes moved but conversely as late as 1770 it was common for only the lower half to slide. In the late 1700s larger window openings, sometimes to the floor became popular and by 1851 the single pane of glass had been developed and started to replace small panes.

The sash windows in the three cottages were set in pairs and had 4 panes to each sash, as shown in the headline photograph, though it is not known if these are originals. In fact, the glazing bars between the panes are more slender than those first used in sashes, suggesting types from the late 1700s or early 1800s. The London building Acts of 1707 and 1709 required windows to be set back from the wall face by 4 inches and this change affected other parts of the country gradually. The cottage windows are set back and have plain window sills and flat architraves surrounding the other three sides flush to the walls. Only the porch over the front door had stone moulded consoles to support it in the style of the 1700s.

The Buildings

The three cottages owned by my family were possibly built at different times. The third cottage is lower in height and has a large garden sloping away down the hill. The long narrow gardens of the top two were at the front of the row with a side wall to the road running around Kingsdown Hill. On the back of these three was a tiny cottage facing in the Box direction. In the 1909 National Land Survey the cottages are classed old and their condition only fair. By the early 1980s not much had changed in the outward appearance of these dwellings but internally quite a bit had altered, as one might expect.

The construction of these cottages is true to Georgian building form with the front façades faced with smooth ashlar on the outside. This was the posh front on view to the public. Ashlar blocks were laid in even courses with almost invisible hairline mortar joints between them to give the wall as even and seamless an appearance as possible and then the entire façade would be combed down with a mason's drag which resembled a large toothed comb to smooth out any blemishes. The remarks by the great Bath architect John Wood on Bath ashlar stone are apt: he confirmed that the free stone used was beyond dispute a most excellent building material, being beautiful, durable and cheap. But he insinuated that, because the blocks were transported ready-wrought to site, the sharp edges and corners of this stone generally broke and the neatness of the joints and sharpness in the edges of the mouldings was lost. The fronts of the Kingsdown cottages are rather like this in quality and with a weathered look gained over the years.

As ashlar was an expensive material, only one depth of this dressed stone on the façade was used and immediately behind it the rougher-looking rubble stone was used. The rubble and ashlar walls were tied together at intervals by the longer bonding stones which projected from the ashlar face into the rubble core. This rubble stone was either cut from the leftover waste from larger blocks, or quarried from other beds in the quarry. The rubble stone would be tightly packed in the same way as in a drystone wall often in courses with copious amounts of lime and mortar filling the crevices and voids and this also helped spread the load. Oyster shells or pieces of slate were used to back the joints, oysters not being the delicacy they are today, but eaten in plenty in previous times.

The fronts of the three cottages have a single decoration of a plat band protruding slightly between the ground and first floor, but the backs of the cottages are just rubble. They had elegant ashlar chimneys each with two moulded narrow bands.

Sash windows for cottages were becoming popular about 1692 and by 1720 had become very fashionable, suiting the symmetry of grand Palladian architecture in towns and cities. They did not rattle like the old casement windows, needed very little maintenance and had the advantage of allowing in more light than the diamond-shaped panes, each sash being square usually with 9 small panes in it. As early as 1701 both sashes moved but conversely as late as 1770 it was common for only the lower half to slide. In the late 1700s larger window openings, sometimes to the floor became popular and by 1851 the single pane of glass had been developed and started to replace small panes.

The sash windows in the three cottages were set in pairs and had 4 panes to each sash, as shown in the headline photograph, though it is not known if these are originals. In fact, the glazing bars between the panes are more slender than those first used in sashes, suggesting types from the late 1700s or early 1800s. The London building Acts of 1707 and 1709 required windows to be set back from the wall face by 4 inches and this change affected other parts of the country gradually. The cottage windows are set back and have plain window sills and flat architraves surrounding the other three sides flush to the walls. Only the porch over the front door had stone moulded consoles to support it in the style of the 1700s.

Inside the Cottages

In the 1891 census Mary Betteridge, widow, was classed as head of the house with her son-in-law, George Betteridge, his wife Charlotte (nee Smith) and their first four children living there. These were to increase to six during their stay in her house. How they all fitted into the tiny premises, we’ll never know, but they did.

The 1909 valuation confirms that the middle cottage had an attic, one bedroom, and on the ground floor a kitchen and pantry.

The attic was also used as a bedroom, however, and this attic went right through and over the top of the adjoining cottage 1.

The lower cottage had 2 bedrooms up, kitchen and pantry down and these two properties shared an outside washhouse and closet. Ash Cottage had two bedrooms up, kitchen and washhouse down and an outside closet. This is how I remember them in the 1950s and 60s as a child. My mother remembered that in the 1920s there was a door linking these two cottages which was visible from the top cottage in the main living room but not visible in the pantry of the middle cottage.

Within living memory, the staircase for cottages 1 and 2 was in the middle of the whole row and, when Ash Cottage was sealed off from Vine Cottage, a staircase had to be added to it. Interestingly, Cottage 3 had its staircase on the front garden side and next to the middle cottage. This original stone staircase has since been replaced.

In the late 1970s, Vine Cottage had a tiny bathroom put in one part of the one bedroom, one of the few alterations made to that cottage during our family ownership. The floors were stone flagged with rugs on top; the pantry had become a makeshift kitchen; and the former kitchen was now the living room. As there was no room for a dining room, a table in the middle of the floor was used for meals. There was hardly room to swing a cat. The attic was still used as a guest room and beams had to be climbed over to get to the bed which stood under the sloping roof. As children we could just stand up there. The outside privy had been used by us all in its time but had now become defunct. This was constantly moved as fresh earth was required to soak away the effluent. At one time, my ancestors kept a ferret shed next door to it and chickens in a run at the end of the garden, winning medals for them at the Bathford Show.

There have been further alterations to the properties in recent years. The front of Vine Cottage has been altered with a modern lean-to porch which has affected the appearance of the original stone front. There are more alterations at The Cottage (the third one in the original row) where the owners have purchased the tiny cottage on the back of Vine Cottage (known as Keeler's Cottage) and knocked through the end wall turning it into their entrance hall, with a further extension built on the valley side. During the renovations, the original stone staircase in this lower cottage was uncovered and this was situated on the inside of the front wall, the front door of the dwelling being to the rear opposite it. The gardens have been severally split up, the lower garden being landscaped down the slope of the hillside and there is no path running along the front of the row any more.

In the 1891 census Mary Betteridge, widow, was classed as head of the house with her son-in-law, George Betteridge, his wife Charlotte (nee Smith) and their first four children living there. These were to increase to six during their stay in her house. How they all fitted into the tiny premises, we’ll never know, but they did.

The 1909 valuation confirms that the middle cottage had an attic, one bedroom, and on the ground floor a kitchen and pantry.

The attic was also used as a bedroom, however, and this attic went right through and over the top of the adjoining cottage 1.

The lower cottage had 2 bedrooms up, kitchen and pantry down and these two properties shared an outside washhouse and closet. Ash Cottage had two bedrooms up, kitchen and washhouse down and an outside closet. This is how I remember them in the 1950s and 60s as a child. My mother remembered that in the 1920s there was a door linking these two cottages which was visible from the top cottage in the main living room but not visible in the pantry of the middle cottage.

Within living memory, the staircase for cottages 1 and 2 was in the middle of the whole row and, when Ash Cottage was sealed off from Vine Cottage, a staircase had to be added to it. Interestingly, Cottage 3 had its staircase on the front garden side and next to the middle cottage. This original stone staircase has since been replaced.

In the late 1970s, Vine Cottage had a tiny bathroom put in one part of the one bedroom, one of the few alterations made to that cottage during our family ownership. The floors were stone flagged with rugs on top; the pantry had become a makeshift kitchen; and the former kitchen was now the living room. As there was no room for a dining room, a table in the middle of the floor was used for meals. There was hardly room to swing a cat. The attic was still used as a guest room and beams had to be climbed over to get to the bed which stood under the sloping roof. As children we could just stand up there. The outside privy had been used by us all in its time but had now become defunct. This was constantly moved as fresh earth was required to soak away the effluent. At one time, my ancestors kept a ferret shed next door to it and chickens in a run at the end of the garden, winning medals for them at the Bathford Show.

There have been further alterations to the properties in recent years. The front of Vine Cottage has been altered with a modern lean-to porch which has affected the appearance of the original stone front. There are more alterations at The Cottage (the third one in the original row) where the owners have purchased the tiny cottage on the back of Vine Cottage (known as Keeler's Cottage) and knocked through the end wall turning it into their entrance hall, with a further extension built on the valley side. During the renovations, the original stone staircase in this lower cottage was uncovered and this was situated on the inside of the front wall, the front door of the dwelling being to the rear opposite it. The gardens have been severally split up, the lower garden being landscaped down the slope of the hillside and there is no path running along the front of the row any more.

Cottage Names

The names of the cottages weren’t clear until recent times. This makes it uncertain which families lived in any particular property. We shall see more of this in part 2 of the article in the next issue of the website. For example, George Ford (b 21 December 1879-20 July 1947) married Frances Beatrice Merrett (b 3 June 1884) in 1907 and they lived with George’s father James, next to the Salmon family in Tyning Cottage in 1911. On the other side of James was Edwin Ford (probably in properties now called Down Under or Tumble Down), then William Robert Ashley and separately George Archer in Cottages 2 and 3, then Wallace Ford, probably in Laurel. This means that Vine was either unoccupied or missed at this point in the census.

Naming the cottages didn’t always make addresses clearer. The top cottage had passed into the ownership of a family member called Jacob Smith. After his death in 1880, his widow Emma (1851-1946) still owned the cottage and married a man called Jack Ash. This cottage is currently called Ash Cottage but the name has no known connection to Jack.

By November 1950, my uncle and aunt, Charles and Amy Freeme, had moved into the middle cottage (Number 2) and renamed it Jasmine Cottage. This wasn’t helpful as the property next door but one to Ash Cottage was called Jessamine. Jasmine Cottage was again renamed in 1961 when the voters lists for this and the ensuing year call it Vic Cottage. In 1964, the Freemes were noted as living at No. 1 The Cottage, Kingsdown, and the remaining two are not readily identifiable from the electoral rolls. By 1965 the middle cottage was called Vine Cottage and the name The Cottage was reserved for the use of the lower property occupied by Thomas and Nellie Robbins.

In the next issue Jane reviews the families who lived in the Kingsdown Cottages and, for the first time, sheds light on the people who developed the Kingsdown area.

The names of the cottages weren’t clear until recent times. This makes it uncertain which families lived in any particular property. We shall see more of this in part 2 of the article in the next issue of the website. For example, George Ford (b 21 December 1879-20 July 1947) married Frances Beatrice Merrett (b 3 June 1884) in 1907 and they lived with George’s father James, next to the Salmon family in Tyning Cottage in 1911. On the other side of James was Edwin Ford (probably in properties now called Down Under or Tumble Down), then William Robert Ashley and separately George Archer in Cottages 2 and 3, then Wallace Ford, probably in Laurel. This means that Vine was either unoccupied or missed at this point in the census.

Naming the cottages didn’t always make addresses clearer. The top cottage had passed into the ownership of a family member called Jacob Smith. After his death in 1880, his widow Emma (1851-1946) still owned the cottage and married a man called Jack Ash. This cottage is currently called Ash Cottage but the name has no known connection to Jack.

By November 1950, my uncle and aunt, Charles and Amy Freeme, had moved into the middle cottage (Number 2) and renamed it Jasmine Cottage. This wasn’t helpful as the property next door but one to Ash Cottage was called Jessamine. Jasmine Cottage was again renamed in 1961 when the voters lists for this and the ensuing year call it Vic Cottage. In 1964, the Freemes were noted as living at No. 1 The Cottage, Kingsdown, and the remaining two are not readily identifiable from the electoral rolls. By 1965 the middle cottage was called Vine Cottage and the name The Cottage was reserved for the use of the lower property occupied by Thomas and Nellie Robbins.

In the next issue Jane reviews the families who lived in the Kingsdown Cottages and, for the first time, sheds light on the people who developed the Kingsdown area.

Sources

Box Land Tax assessment 1780-1831 WRO A1/345/45

Box rates 1820-30 WRO 1719/19

Box Tithe Map and Apportionment 1838 WRO

Survey of Box 1842

1841-1911 Census for Kingsdown, Box

Land Valuation 1909 Box PRO IR/58/81598/81600

Will of Jacob Newman of Bathford PCC London 1853

Will of James Newman of Bathford proved London 1876

Admon. John Newman Bristol 1871

Will of William Hiscocks Newman proved Bristol 1901

Will of Mary Betteridge proved Salisbury 1905

Electoral Rolls Box 1837-1970

Bath Trade Directories

Family photographs.

Box Land Tax assessment 1780-1831 WRO A1/345/45

Box rates 1820-30 WRO 1719/19

Box Tithe Map and Apportionment 1838 WRO

Survey of Box 1842

1841-1911 Census for Kingsdown, Box

Land Valuation 1909 Box PRO IR/58/81598/81600

Will of Jacob Newman of Bathford PCC London 1853

Will of James Newman of Bathford proved London 1876

Admon. John Newman Bristol 1871

Will of William Hiscocks Newman proved Bristol 1901

Will of Mary Betteridge proved Salisbury 1905

Electoral Rolls Box 1837-1970

Bath Trade Directories

Family photographs.

Reference

[1] Newman family anecdotes but my mother insisted this resembles Queen Victoria rather than Queen Anne

[1] Newman family anecdotes but my mother insisted this resembles Queen Victoria rather than Queen Anne