|

JDB Erskine Lewis Jones December 2022 When long-term, structural unemployment hits an area, the results can destroy as much as a local explosion or landslip. This last happened in Box over a century ago with the decline of the stone industry and the aftermath of the Great War. It was a difficult time for everyone as society began to come to terms with the new society brought by the war. In addition to that, economic collapse devastated the lives of many elderly, local families who found themselves unable to relocate for reasons of family commitments, lack of retraining possibilities and the consequences of unemployment after the First World War. “Cometh the hour, cometh the man” and an unexpected hero arose in Box in the shape of a most exceptional man, Colonel John David Beveridge Erskine. An experienced and highly-decorated soldier, JDB Erskine was tireless in his efforts to get assistance to unemployed local men. JDB Erskine (courtesy V&A Lafayette http://lafayette.org.uk/ers9326.html) |

Personal Life

John David Beveridge Erskine (3 April 1874-11 May 1926) was born at Brignall, Teesdale, County Durham, near his father’s home at Wycliffe, Barnard Castle. His childhood was conventional and very middle-class. He was the only son of a vicar, the Rev John Erskine (1830-1902) a former Royal Navy chaplain, and his wife Amelia Beveridge (1835-13 April 1926). The parents were widely travelled, father from Ireland and mother from Dunfermline, Scotland, and in the 1860s they lived at Pembrokeshire, Wales. The Rev John retired from the navy in 1870 and undertook various clerical duties, before settling in Bristol and later moving to Lyncombe Vale, Bath in the 1880s.[1]

JDB was their last child and had five older sisters. The Erskine children were partly taught at home by a governess and in 1891 John and his mother were lodging in Cheltenham, separate from Rev John and the other children. JDB later attended school at Bath College before entering military service in the 1890s.[2] The mother, Amelia, was the daughter of Erskine Beveridge and the parents may have been related as distant cousins.

JDB’s later life was personally troubled, however and his first marriage on 13 January 1903 ended in tragedy. Shortly after his return from South Africa, he married Violet Eveline (Dolly) Grieveson (1876-1903) from Harrogate.[3] They settled at Ashton-under-Lyne, Manchester, close to the regiment headquarters, and had a child David Beveridge in October that year. Shortly after the birth, Dolly contracted scarlet fever and, in a period before antibiotics, she died shortly after. JDB later married Ethel Naomi Gwendoline Robertson (1875-1954) on 3 January 1907. She was daughter of Straun Robertson of Batheaston. The Robertson family were well-known in the local area and one branch lived in Box for many decades at Middlehill and Ditteridge.[4] At the reception, the cutting of the wedding cake took a special role because, in accordance with family custom, JDB cut the slices using his military sword.[5] JDB and his wife moved to Middlehill House before 1915 according to the electoral roll of that year.

John David Beveridge Erskine (3 April 1874-11 May 1926) was born at Brignall, Teesdale, County Durham, near his father’s home at Wycliffe, Barnard Castle. His childhood was conventional and very middle-class. He was the only son of a vicar, the Rev John Erskine (1830-1902) a former Royal Navy chaplain, and his wife Amelia Beveridge (1835-13 April 1926). The parents were widely travelled, father from Ireland and mother from Dunfermline, Scotland, and in the 1860s they lived at Pembrokeshire, Wales. The Rev John retired from the navy in 1870 and undertook various clerical duties, before settling in Bristol and later moving to Lyncombe Vale, Bath in the 1880s.[1]

JDB was their last child and had five older sisters. The Erskine children were partly taught at home by a governess and in 1891 John and his mother were lodging in Cheltenham, separate from Rev John and the other children. JDB later attended school at Bath College before entering military service in the 1890s.[2] The mother, Amelia, was the daughter of Erskine Beveridge and the parents may have been related as distant cousins.

JDB’s later life was personally troubled, however and his first marriage on 13 January 1903 ended in tragedy. Shortly after his return from South Africa, he married Violet Eveline (Dolly) Grieveson (1876-1903) from Harrogate.[3] They settled at Ashton-under-Lyne, Manchester, close to the regiment headquarters, and had a child David Beveridge in October that year. Shortly after the birth, Dolly contracted scarlet fever and, in a period before antibiotics, she died shortly after. JDB later married Ethel Naomi Gwendoline Robertson (1875-1954) on 3 January 1907. She was daughter of Straun Robertson of Batheaston. The Robertson family were well-known in the local area and one branch lived in Box for many decades at Middlehill and Ditteridge.[4] At the reception, the cutting of the wedding cake took a special role because, in accordance with family custom, JDB cut the slices using his military sword.[5] JDB and his wife moved to Middlehill House before 1915 according to the electoral roll of that year.

JDB’s Military Career

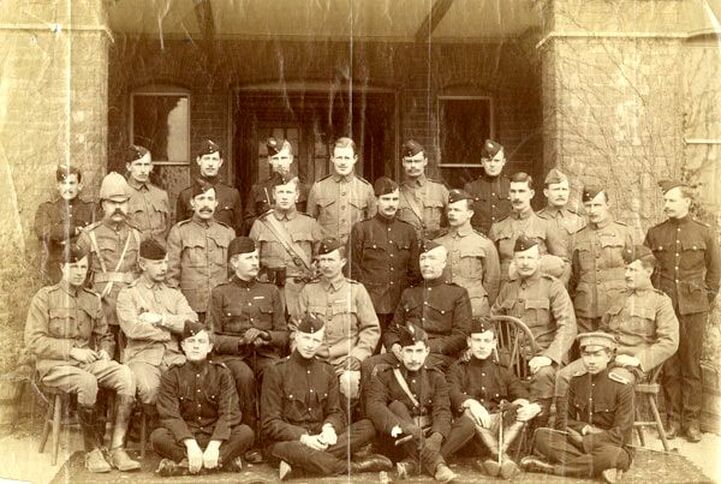

Before his move to Box, JDB had a most distinguished military career, with a rapid rise through officer ranks and numerous citations and awards. He joined the militia as Second Lieutenant in the 4th Border Battalion of the Westmoreland and Cumberland Regiment (based at Carlisle) in 1893 before transfer to the Manchester Regiment in 1896.[6] He served in the Boer War between 1899 and 1902 receiving the Queen’s Medal with three clasps for individual citations and the King’s Medal with two clasps. He was promoted to Captain and initially retired in September 1911 and returned to the south-west of England close to his family and those of his wife Ethel from Batheaston.

He was a popular soldier, not afraid to show his character to others. At the Farnham Amateur Dramatic Society in 1894, he entertained the group with the rendering of a song in character of “I’ll ne’er forget my Martha” and even continued singing in fundraising for ex-servicemen until near the end of his life.[7]

Before his move to Box, JDB had a most distinguished military career, with a rapid rise through officer ranks and numerous citations and awards. He joined the militia as Second Lieutenant in the 4th Border Battalion of the Westmoreland and Cumberland Regiment (based at Carlisle) in 1893 before transfer to the Manchester Regiment in 1896.[6] He served in the Boer War between 1899 and 1902 receiving the Queen’s Medal with three clasps for individual citations and the King’s Medal with two clasps. He was promoted to Captain and initially retired in September 1911 and returned to the south-west of England close to his family and those of his wife Ethel from Batheaston.

He was a popular soldier, not afraid to show his character to others. At the Farnham Amateur Dramatic Society in 1894, he entertained the group with the rendering of a song in character of “I’ll ne’er forget my Martha” and even continued singing in fundraising for ex-servicemen until near the end of his life.[7]

Service in World War I

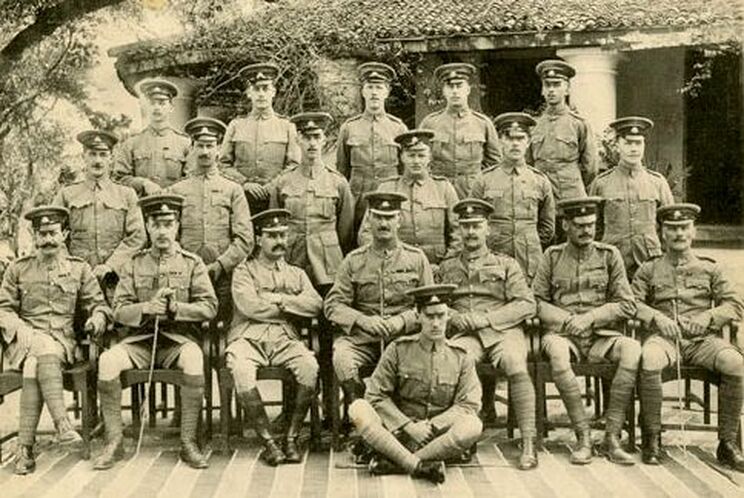

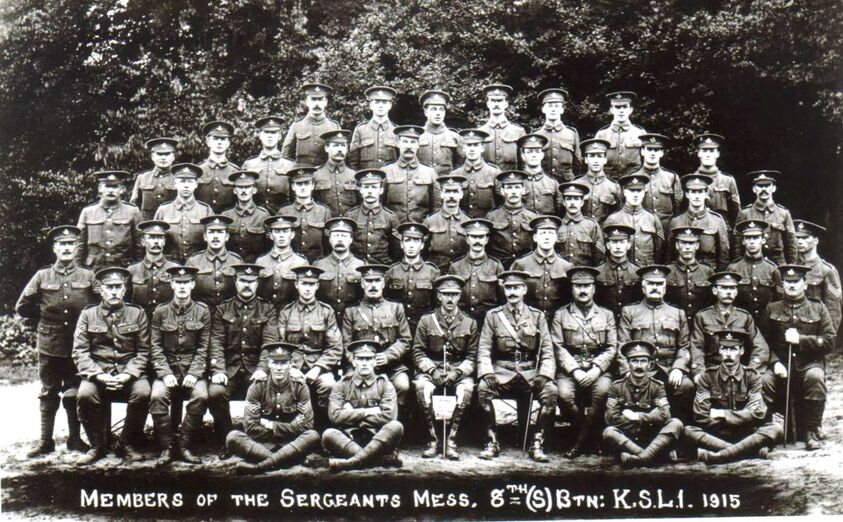

All of this changed dramatically with the outbreak of the Great War. JDB returned to service as Temporary Major in September 1914. He joined the 8th Shropshire Light Infantry in March 1915, a new battalion which had been raised at Shrewsbury as part of an appeal by Lord Kitchener. His previous experience and fluency in French saw him appointed Temporary Lieutenant Colonel.[8] After a brief spell working on the defences for London, the battalion embarked to the front line on the Western Front digging trenches at Hébuterne and Amiens. It is possible that JDB, his wife and children relocated to Box at this time, presumably so that Ethel could be closer to her family when JDB was away.

On 28 October 1915 the regiment was deployed to Salonika, initially engaged in training, road building and defence construction. In early November 1916 the regiment took over trenches that became the Front Line north of Ardzan and, for successful completion of the work, JDB was promoted to Major. Salonika was a difficult terrain, mountainous with steep ridges and deep gorges in the north and swampy in the south. From a logistical point of view the area was poorly served by roads and the Allies were at the end of a long lifeline served by shipping and a single railway. The climate was one of extremes with great heat in the summer and bitterly cold winters, especially in the higher altitudes. Malaria was prevalent in the swampy areas which were served by many pools, ponds, lakes and rivers. Poor health was a constant companion for members of the regiment with over 162,000 cases of malaria recorded.

By 24 April 1917 the Allied Army intended to breakout of their defensive positions in the Balkans. This was to be achieved by a major assault at 20:45 in the direction of Vardar and Doiran against the firmly entrenched Bulgarian Army. The 8th KSLI role in this battle was to capture and hold the enemy positions. By 23:05 the battalion had captured the positions and successfully fought off Bulgarian counter attacks. The battalion suffered 13 killed, 115 wounded and 2 missing.

The battalion continued to strengthen British defences and train new drafts over the following months. By September 1918 it fell to the battalion to further assault the enemy’s position in order to prevent enemy reinforcements being sent to a sector of a planned assault by the French, on the occasion the battalion were to act as vanguard on an assault of ‘pip ridge’. The 8 KSLI advanced at dawn on 18 September, however a combination of heavy Bulgarian artillery bombardment and machine gun fire on a narrow front crushed the Allied attack and the enemy positions remained secure. The 66th Infantry Brigade lost about two thirds of its effective strength (37 officers and about 800 other ranks) of which the 8th Kings Light Infantry division lost 46 killed and 119 wounded. Although the offensive at Doiran had failed, an offensive by the French and Greek Armies in the Vardar valley succeeded, forcing the Bulgarian Army to retreat and to surrender at the end of September.

All of this changed dramatically with the outbreak of the Great War. JDB returned to service as Temporary Major in September 1914. He joined the 8th Shropshire Light Infantry in March 1915, a new battalion which had been raised at Shrewsbury as part of an appeal by Lord Kitchener. His previous experience and fluency in French saw him appointed Temporary Lieutenant Colonel.[8] After a brief spell working on the defences for London, the battalion embarked to the front line on the Western Front digging trenches at Hébuterne and Amiens. It is possible that JDB, his wife and children relocated to Box at this time, presumably so that Ethel could be closer to her family when JDB was away.

On 28 October 1915 the regiment was deployed to Salonika, initially engaged in training, road building and defence construction. In early November 1916 the regiment took over trenches that became the Front Line north of Ardzan and, for successful completion of the work, JDB was promoted to Major. Salonika was a difficult terrain, mountainous with steep ridges and deep gorges in the north and swampy in the south. From a logistical point of view the area was poorly served by roads and the Allies were at the end of a long lifeline served by shipping and a single railway. The climate was one of extremes with great heat in the summer and bitterly cold winters, especially in the higher altitudes. Malaria was prevalent in the swampy areas which were served by many pools, ponds, lakes and rivers. Poor health was a constant companion for members of the regiment with over 162,000 cases of malaria recorded.

By 24 April 1917 the Allied Army intended to breakout of their defensive positions in the Balkans. This was to be achieved by a major assault at 20:45 in the direction of Vardar and Doiran against the firmly entrenched Bulgarian Army. The 8th KSLI role in this battle was to capture and hold the enemy positions. By 23:05 the battalion had captured the positions and successfully fought off Bulgarian counter attacks. The battalion suffered 13 killed, 115 wounded and 2 missing.

The battalion continued to strengthen British defences and train new drafts over the following months. By September 1918 it fell to the battalion to further assault the enemy’s position in order to prevent enemy reinforcements being sent to a sector of a planned assault by the French, on the occasion the battalion were to act as vanguard on an assault of ‘pip ridge’. The 8 KSLI advanced at dawn on 18 September, however a combination of heavy Bulgarian artillery bombardment and machine gun fire on a narrow front crushed the Allied attack and the enemy positions remained secure. The 66th Infantry Brigade lost about two thirds of its effective strength (37 officers and about 800 other ranks) of which the 8th Kings Light Infantry division lost 46 killed and 119 wounded. Although the offensive at Doiran had failed, an offensive by the French and Greek Armies in the Vardar valley succeeded, forcing the Bulgarian Army to retreat and to surrender at the end of September.

Commendations

JDB was awarded the DSO {Distinguished Service Order for actual combat) and the Croix de Guerre with palms (citations) awarded by the French President in 1917.[9] His service was typified by his award of a Brevet (entitlement to a higher military rank because of personal bravery). We get a remarkably vivid description of the commendation that was awarded to him in September 1918.[10] The Bulgarians had taken a high defensive position by tunnelling through a hilltop giving them visibility of British troops below. Nonetheless, it was decided that the 66th Infantry Brigade would be part of an attack launched on the ridge. The first assault by the brigade began to fail and the commanding officers of the first two battalions were killed or wounded. JDB rallied the remaining fighting force of the brigade on his position. For some time he commanded only 4 officers and 240 men. The brigade lost 37 officers and 800 other ranks in the assault, amounting to 65% of its effective strength.

JDB was demobilized in April 1919, having completed 19 years and 331 days of regular army service for which he received a pension of £142 a year. (Because this was less than 20 years-service, his widow and children were refused a widow’s pension after his death.[11] JDB’s military career was a spectacular and highly-meritorious service to the nation. For many men, it would have been sufficient but for JDB it was just the start of an equally-distinguished mission in local public service.

JDB was awarded the DSO {Distinguished Service Order for actual combat) and the Croix de Guerre with palms (citations) awarded by the French President in 1917.[9] His service was typified by his award of a Brevet (entitlement to a higher military rank because of personal bravery). We get a remarkably vivid description of the commendation that was awarded to him in September 1918.[10] The Bulgarians had taken a high defensive position by tunnelling through a hilltop giving them visibility of British troops below. Nonetheless, it was decided that the 66th Infantry Brigade would be part of an attack launched on the ridge. The first assault by the brigade began to fail and the commanding officers of the first two battalions were killed or wounded. JDB rallied the remaining fighting force of the brigade on his position. For some time he commanded only 4 officers and 240 men. The brigade lost 37 officers and 800 other ranks in the assault, amounting to 65% of its effective strength.

JDB was demobilized in April 1919, having completed 19 years and 331 days of regular army service for which he received a pension of £142 a year. (Because this was less than 20 years-service, his widow and children were refused a widow’s pension after his death.[11] JDB’s military career was a spectacular and highly-meritorious service to the nation. For many men, it would have been sufficient but for JDB it was just the start of an equally-distinguished mission in local public service.

Caring for Others after the War

Not content with the situation of ex-servicemen after the Great War, JDB fronted the efforts to help and protect ex-soldiers and their families after the war. Against a tide of national economic decline, political failure and worker strikes, JDB sought to provide employment and social companionship for ex-soldiers. The situation of ex-servicemen after the war was desperate. Scores of soldiers returned to Box village to resume civilian life often without a job or career training, many with physical or psychological disabilities, at a time when the nation was in total economic melt-down. Some men sat outside their house with a sign around their neck Served in HM Forces 1914-18 in the hope that passers-by could offer work and wages. For others, war memories haunted them so much that they withdrew from society and avoided contact with others apart from former comrades.

In 1919 JDB led the initiative to start a branch of the Box Old Comrades Club in a room in the Old Clock House. This arrangement could only be a temporary location as the area was being re-developed and nearby properties were demolished to build the Box

Co-operative Shop (McColls) in 1925.[12] Various premises were considered for a permanent base and it was decided to buy Alpha House (now called Hardy House) on the High Street for £1,050 (today equivalent to £60,000). The commitment to develop a club for war comrades in Box was remarkably early and predated the formation of the British Legion. JDB promoted the cause amongst other notable village residents. A grant of £165 was received and local people made donations and bought loan-stock. The organisation was still in its infancy. A bank loan was required and a committee, specified rules and club responsibilities. JDB took the role of Honorary Secretary to supervise arrangements. On 10 December 1921, the clubhouse was officially opened by lord of the manor, George Edward Wilbraham Northey, and club president, Colonel Marcus Rainsford.

Whilst the Comrades Club could offer comfort and comradeship to local servicemen, it could not give them money for their maintenance. The village authorities reported on the dire situation in Box, including the vicar Sweetapple in the parish magazine: May God stir Box to caste off lethargy and carelessness (February 1923); The grave difficulties of our times (December 1923); and We would remind any lads thinking of seeking a career in another land of the splendid opportunities offered by the Australian government (January 1924). Once the club was formed, JDB started a second organisation, the Box Relief Fund, to offer active assistance rather than comfort and comradeship. Along with a colleague Captain Roger Alexander Legard (1891-1972) and support from the British Legion, the aim was to find potential employers who could offer paid work to ex-servicemen. JDB was appointed chairman and the club long outlived him. At a time when many local businesses were closing or going bankrupt, it was often just private people wanting small gardening or handyman jobs but it gave encouragement and wages to men who otherwise had nothing.[13]

Not content with the situation of ex-servicemen after the Great War, JDB fronted the efforts to help and protect ex-soldiers and their families after the war. Against a tide of national economic decline, political failure and worker strikes, JDB sought to provide employment and social companionship for ex-soldiers. The situation of ex-servicemen after the war was desperate. Scores of soldiers returned to Box village to resume civilian life often without a job or career training, many with physical or psychological disabilities, at a time when the nation was in total economic melt-down. Some men sat outside their house with a sign around their neck Served in HM Forces 1914-18 in the hope that passers-by could offer work and wages. For others, war memories haunted them so much that they withdrew from society and avoided contact with others apart from former comrades.

In 1919 JDB led the initiative to start a branch of the Box Old Comrades Club in a room in the Old Clock House. This arrangement could only be a temporary location as the area was being re-developed and nearby properties were demolished to build the Box

Co-operative Shop (McColls) in 1925.[12] Various premises were considered for a permanent base and it was decided to buy Alpha House (now called Hardy House) on the High Street for £1,050 (today equivalent to £60,000). The commitment to develop a club for war comrades in Box was remarkably early and predated the formation of the British Legion. JDB promoted the cause amongst other notable village residents. A grant of £165 was received and local people made donations and bought loan-stock. The organisation was still in its infancy. A bank loan was required and a committee, specified rules and club responsibilities. JDB took the role of Honorary Secretary to supervise arrangements. On 10 December 1921, the clubhouse was officially opened by lord of the manor, George Edward Wilbraham Northey, and club president, Colonel Marcus Rainsford.

Whilst the Comrades Club could offer comfort and comradeship to local servicemen, it could not give them money for their maintenance. The village authorities reported on the dire situation in Box, including the vicar Sweetapple in the parish magazine: May God stir Box to caste off lethargy and carelessness (February 1923); The grave difficulties of our times (December 1923); and We would remind any lads thinking of seeking a career in another land of the splendid opportunities offered by the Australian government (January 1924). Once the club was formed, JDB started a second organisation, the Box Relief Fund, to offer active assistance rather than comfort and comradeship. Along with a colleague Captain Roger Alexander Legard (1891-1972) and support from the British Legion, the aim was to find potential employers who could offer paid work to ex-servicemen. JDB was appointed chairman and the club long outlived him. At a time when many local businesses were closing or going bankrupt, it was often just private people wanting small gardening or handyman jobs but it gave encouragement and wages to men who otherwise had nothing.[13]

The fashionable marriage of daughter Elizabeth and James Erskine (courtesy North Wilts Herald, 17 March 1933)

Conclusion

JDB Erskine died on 11 May 1926 at Middlehill House and his funeral was attended by his family, other military families in Box and sixty ex-servicemen from the Comrades Club.[14] In his will he left £23,386 (today about a million and a half) to his widow Ethel and all his medals, military documents, the flag of the 8th King’s Shropshire Battalion and service photographs to his wife for life and then to his son as a reminder of our duty and privilege always to serve our Sovereign and country.[15] Ethel continued to live at Middlehill House and both of their daughters were married in Box Church as well as their grandson, James David.[16]

The family sold it to Esther Mary McCarthy on 15 April 1948.

JDB Erskine’s local efforts to turn the tide of a seemingly inexhaustible national tragedy were quite remarkable. He cared for people when many others were just commentators. After the war he explained his commitment to ex-servicemen: I saw these wonderful men live and I saw many die and I formed the resolve that, if I returned to England, I would do all I could to help those who came through the war.[17]

JDB Erskine died on 11 May 1926 at Middlehill House and his funeral was attended by his family, other military families in Box and sixty ex-servicemen from the Comrades Club.[14] In his will he left £23,386 (today about a million and a half) to his widow Ethel and all his medals, military documents, the flag of the 8th King’s Shropshire Battalion and service photographs to his wife for life and then to his son as a reminder of our duty and privilege always to serve our Sovereign and country.[15] Ethel continued to live at Middlehill House and both of their daughters were married in Box Church as well as their grandson, James David.[16]

The family sold it to Esther Mary McCarthy on 15 April 1948.

JDB Erskine’s local efforts to turn the tide of a seemingly inexhaustible national tragedy were quite remarkable. He cared for people when many others were just commentators. After the war he explained his commitment to ex-servicemen: I saw these wonderful men live and I saw many die and I formed the resolve that, if I returned to England, I would do all I could to help those who came through the war.[17]

Family Tree

Rev John Erskine (1830-1902) and his wife Amelia (1835-13 April 1926). Children:

Mary N (1861-); Anna W (1865-): Elizabeth Beveridge (1866-1914), unmarried; Sarah Maud (1869-); Irene Jane (1872-1891), unmarried; and John David Beveridge Erskine (1874- 11 May 1926).

John David Beveridge Erskine (3 April 1874- 11 May 1926 at Middlehill House) married twice:

First in January 1903 to Violet Eveline Grieveson from Ripon (1876-1903).

Child David Beveridge (8 October 1903-1984)

Secondly, on 3 January 1907 to Ethel Naomi Gwendoline Robertson (1875-1954). She was daughter of Straun Robertson of Batheaston. Children:

Margaret Elise (1908-1963) who in 1930 married Royal Artillery army officer John Patrick Macdougall Haslam (1908-1979);

Elizabeth Naomi G Erskine (1912-) who in 1933 married her second cousin James Erskine of Belfast.[18]

Rev John Erskine (1830-1902) and his wife Amelia (1835-13 April 1926). Children:

Mary N (1861-); Anna W (1865-): Elizabeth Beveridge (1866-1914), unmarried; Sarah Maud (1869-); Irene Jane (1872-1891), unmarried; and John David Beveridge Erskine (1874- 11 May 1926).

John David Beveridge Erskine (3 April 1874- 11 May 1926 at Middlehill House) married twice:

First in January 1903 to Violet Eveline Grieveson from Ripon (1876-1903).

Child David Beveridge (8 October 1903-1984)

Secondly, on 3 January 1907 to Ethel Naomi Gwendoline Robertson (1875-1954). She was daughter of Straun Robertson of Batheaston. Children:

Margaret Elise (1908-1963) who in 1930 married Royal Artillery army officer John Patrick Macdougall Haslam (1908-1979);

Elizabeth Naomi G Erskine (1912-) who in 1933 married her second cousin James Erskine of Belfast.[18]

Military Service of JDB Erskine

1893-96 Joined the 4th Border Militia as Second Lieutenant [19]

1896 Appointed Lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment [19]

1896-97 Served in the East Indies [20]

1897 Promoted to Lieutenant at Calcutta [21]

1897-98 Served in Aden [20]

1900 Promoted to Captain [19]

1900-1902 Served in the Boer War receiving the Queen’s Medal with three clasps won at Wittebergen, Transvaal and Cape Colony and the King’s Medal with two clasps.[22]

1903 Selected for adjutancy [23]

1905 Promoted to Major [21]

1908-11 Served in Kamptee, India [21]

1911 Retired [24]

1914 Re-joined on the outbreak of Great War, serving on the Western Front, the Salonika Front, commanding the 8th Battalion of the Shropshire Light Infantry. At times, he commanded the 66th Infantry Brigade and the 67th Brigade.[22]

1916 Promoted to substantive Major [19]

1917 Promoted to Brevet Major [25]

1917 Awarded Croix de Guerre [24]

1919 Promoted to Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel [25]

1919 Demobilised [25]

1893-96 Joined the 4th Border Militia as Second Lieutenant [19]

1896 Appointed Lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment [19]

1896-97 Served in the East Indies [20]

1897 Promoted to Lieutenant at Calcutta [21]

1897-98 Served in Aden [20]

1900 Promoted to Captain [19]

1900-1902 Served in the Boer War receiving the Queen’s Medal with three clasps won at Wittebergen, Transvaal and Cape Colony and the King’s Medal with two clasps.[22]

1903 Selected for adjutancy [23]

1905 Promoted to Major [21]

1908-11 Served in Kamptee, India [21]

1911 Retired [24]

1914 Re-joined on the outbreak of Great War, serving on the Western Front, the Salonika Front, commanding the 8th Battalion of the Shropshire Light Infantry. At times, he commanded the 66th Infantry Brigade and the 67th Brigade.[22]

1916 Promoted to substantive Major [19]

1917 Promoted to Brevet Major [25]

1917 Awarded Croix de Guerre [24]

1919 Promoted to Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel [25]

1919 Demobilised [25]

References

[1] The Western Chronicle, 31 December 1886

[2] Bath Chronicle & Weekly Advertiser, 14 June 1900

[3] The Ripon Observer, 15 January 1903

[4] See www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/middlehill-househunting-1850s.html

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 10 January 1907

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1926

[7] West Middlesex Herald, 10 February 1894 and The Wiltshire Times, 17 January 1925

[8] This section is indebted to Soldiers of Shropshire Museum, Home - Soldiers of Shropshire. This is a marvellous website for those who are interested and a visit to the museum is very worthwhile.

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 12 May 1917

[10] Lew Darlington, A Battalion Croix de Guerre, The New Mosquito 13, April 2006

[11] Letter from Paymaster-General, 21 July 1926

[12] See founder member Cecil Lambert’s history of the club at Comrades Club - Box People and Places

[13] Parish Magazine, May 1926 and August 1932

[14] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 May 1926

[15] The Wiltshire Times. 3 July 1926

[16] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 26 February 1938

[17] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[18] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 18 March 1933

[19] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1926

[20] National Archives WO 76/207

[21] Service Record of Manchester Regiment 1911

[22] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1926

[23] Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Adviser, 13 July 1903

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 12 May 1917 and London Gazette, 1 May 1917

[25] JDB Erskine, Claim for Re-assessment of Retired Pay, letter 21 September 1919

[1] The Western Chronicle, 31 December 1886

[2] Bath Chronicle & Weekly Advertiser, 14 June 1900

[3] The Ripon Observer, 15 January 1903

[4] See www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/middlehill-househunting-1850s.html

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 10 January 1907

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1926

[7] West Middlesex Herald, 10 February 1894 and The Wiltshire Times, 17 January 1925

[8] This section is indebted to Soldiers of Shropshire Museum, Home - Soldiers of Shropshire. This is a marvellous website for those who are interested and a visit to the museum is very worthwhile.

[9] The Bath Chronicle, 12 May 1917

[10] Lew Darlington, A Battalion Croix de Guerre, The New Mosquito 13, April 2006

[11] Letter from Paymaster-General, 21 July 1926

[12] See founder member Cecil Lambert’s history of the club at Comrades Club - Box People and Places

[13] Parish Magazine, May 1926 and August 1932

[14] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 22 May 1926

[15] The Wiltshire Times. 3 July 1926

[16] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 26 February 1938

[17] Parish Magazine, May 1926

[18] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 18 March 1933

[19] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1926

[20] National Archives WO 76/207

[21] Service Record of Manchester Regiment 1911

[22] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 15 May 1926

[23] Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Adviser, 13 July 1903

[24] The Bath Chronicle, 12 May 1917 and London Gazette, 1 May 1917

[25] JDB Erskine, Claim for Re-assessment of Retired Pay, letter 21 September 1919