|

Light in the Darkness:

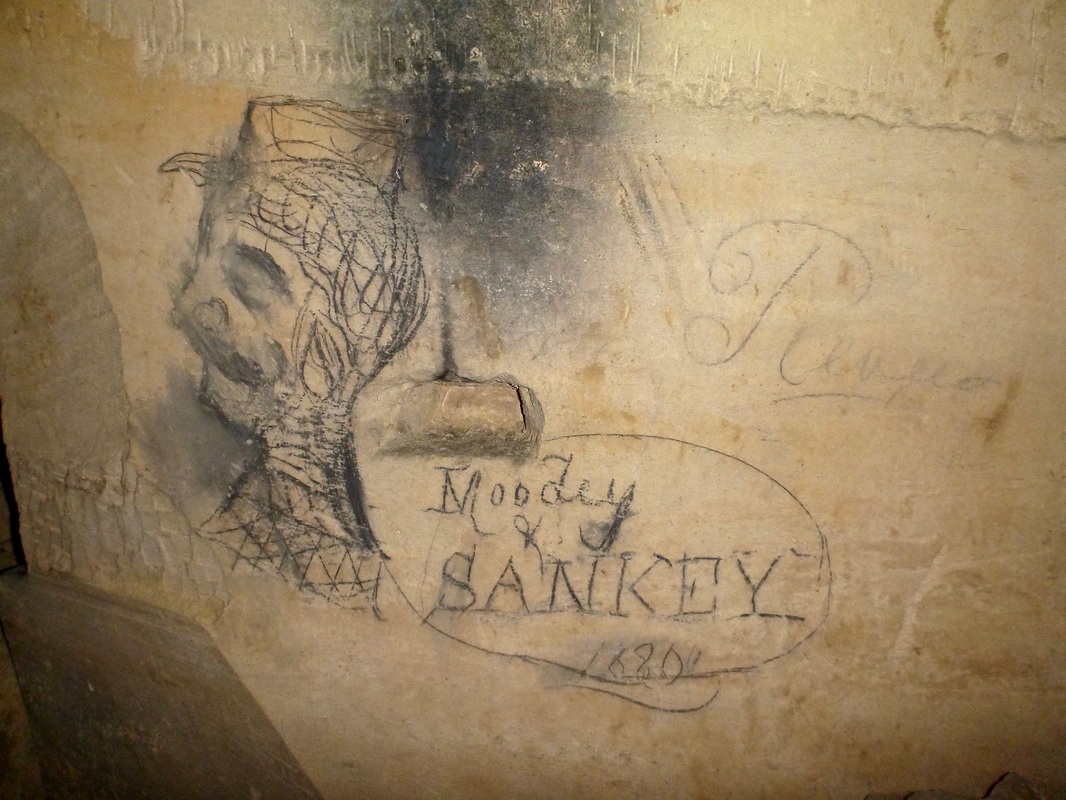

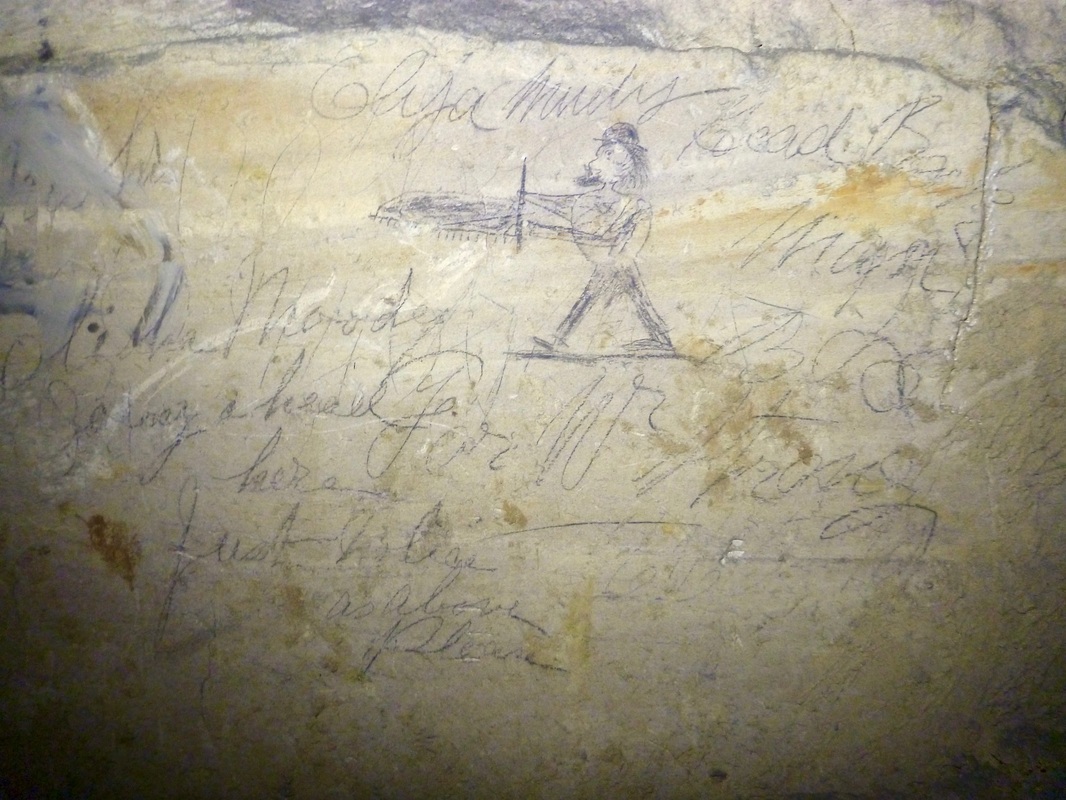

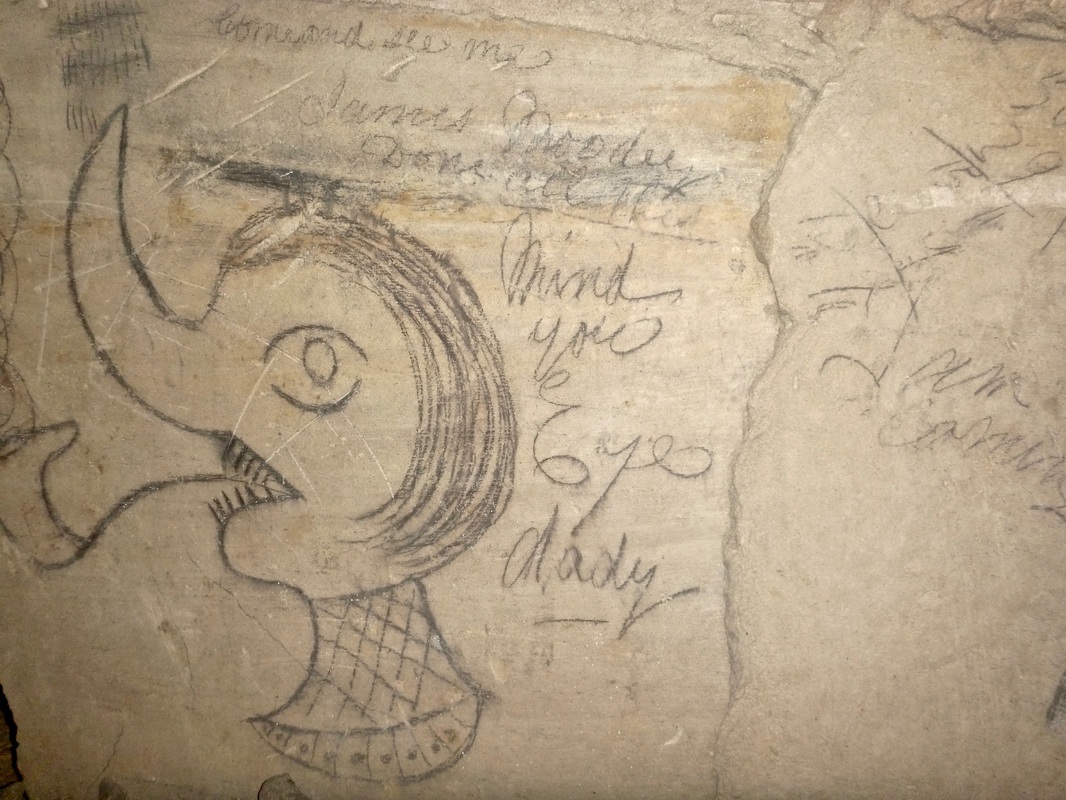

James Moodey, quarryman Mark Jenkinson January 2016 Underground photographs courtesy Mark Jenkinson In this amazing article, Mark reconstructs the life and thoughts of quarryman James Moodey from his underground pictures and writings left in Box's quarries. And is the image here James' attempt to draw a picture of himself? |

The main reason that James Moodey (sometimes spelled Moody) caught my attention is that over my years exploring I realised that I had seen his name all over Box quarry. He was also associated with bold charcoal artwork which catches the eye more than some of the plainer inscriptions, which are found throughout the quarry. Some of his creations are dated and give details of what appears to be his home and his family, as you can see from the photographs below.

We can read too much into these drawings but they do show a person who appears to be larger than life. My interest was roused and I started to find out more about James' life and background.

We can read too much into these drawings but they do show a person who appears to be larger than life. My interest was roused and I started to find out more about James' life and background.

Moodey Family

The earliest reference I found to James was in the 1851 census which shows he was born in 1849 to parents Elisha and Elizabeth. The family were lodgers with Elijah and Mary Ann Moodey, who might have been James' uncle and aunt.

The household was very large. As well as James' family there were the four young children of Elijah and Mary Ann and several other people: James Robinson and his wife Eliza, plus their son George aged 1 month; Joseph Whitaker, James Cornish, William Nowell and William Greenway. All of the men were involved in the quarry trade, two as apprentices. It is probable that the Robinson family were also related to the Moodeys: Eliza was born in the same village as the Moodey men, and George was listed as a grandson to Elijah.[1]

Also unusual was the fact that the house was in Box Village rather than in the shanty towns that arose around the quarry workings at Box Hill, Quarry Hill and other mine entrances, where most quarrymen lived. There is no indication which property they lived in but it appears to be large, perhaps a lodging house, in the centre of the residential area. Or the household could be an early example of a quarry ganger family under the control of James' uncle Elijah. The two apprentices, James Robinson and William Greenway, presumably worked underground and the two older lodgers, Joseph Whitaker and James Cornish, were described as Stone Mason Journeymen implying that they might be working on finishing and selling the stone blocks.

The earliest reference I found to James was in the 1851 census which shows he was born in 1849 to parents Elisha and Elizabeth. The family were lodgers with Elijah and Mary Ann Moodey, who might have been James' uncle and aunt.

The household was very large. As well as James' family there were the four young children of Elijah and Mary Ann and several other people: James Robinson and his wife Eliza, plus their son George aged 1 month; Joseph Whitaker, James Cornish, William Nowell and William Greenway. All of the men were involved in the quarry trade, two as apprentices. It is probable that the Robinson family were also related to the Moodeys: Eliza was born in the same village as the Moodey men, and George was listed as a grandson to Elijah.[1]

Also unusual was the fact that the house was in Box Village rather than in the shanty towns that arose around the quarry workings at Box Hill, Quarry Hill and other mine entrances, where most quarrymen lived. There is no indication which property they lived in but it appears to be large, perhaps a lodging house, in the centre of the residential area. Or the household could be an early example of a quarry ganger family under the control of James' uncle Elijah. The two apprentices, James Robinson and William Greenway, presumably worked underground and the two older lodgers, Joseph Whitaker and James Cornish, were described as Stone Mason Journeymen implying that they might be working on finishing and selling the stone blocks.

|

This old graffiti (right), unfortunately undated, shows Elija Moody Head written at the top which seems to confirm the ganger theory. Perhaps the picture is also of him sawing a block of stone. On the left it says Elisha Moodey and ahead here just ... as above please and possibly For W Strong. Strong was a quarry owner at Box Hill, so perhaps this was where the Moodey family worked.

A decade later, in 1861, James and his parents, Elisha and Elizabeth, were occupying their own house. James was 12 and he had a younger brother, Thomas, aged 4. They occupied the house with lodgers, Elias Snailum (b 1811), blacksmith and what appears to be his son, also Elias Snailum (b 1849), scholar. The repetition of the name Elijah, and similar, implies how close these people were. |

Next door (perhaps the same house as in 1851 but now divided into two properties) was James' uncle and aunt, Elijah and Mary Ann, and three of their children. And also still with them were three Robinson grandchildren, James, Albert and Elijah, together with Thomas Slatford, son-in-law described as stone mason, his wife Eliza J, and their child Anne E.

We can hazard a guess that the location of the property was in the Market Place area of Box because next door lived James and Frances Vezey, who we know from separate information lived at the Chequers Inn. James is described as farmer which is presumed to mean that he had relinquished running the pub and butchery business, prior to his death in 1865.

We need to add a word a word about the meaning of the name Elijah and its derivatives Elias and similar, which permeate the family and their associates. Of course it is the name of a Hebrew prophet of the ninth century before Christ. It is also a badge of belief, meaning My God is Jehovah. It was often used by non-conformist families as a statement of their faith and was popular for the early Puritan settlers in America. It is probable that the Moodey family were a part of a deeply religious, low-church group in Box.

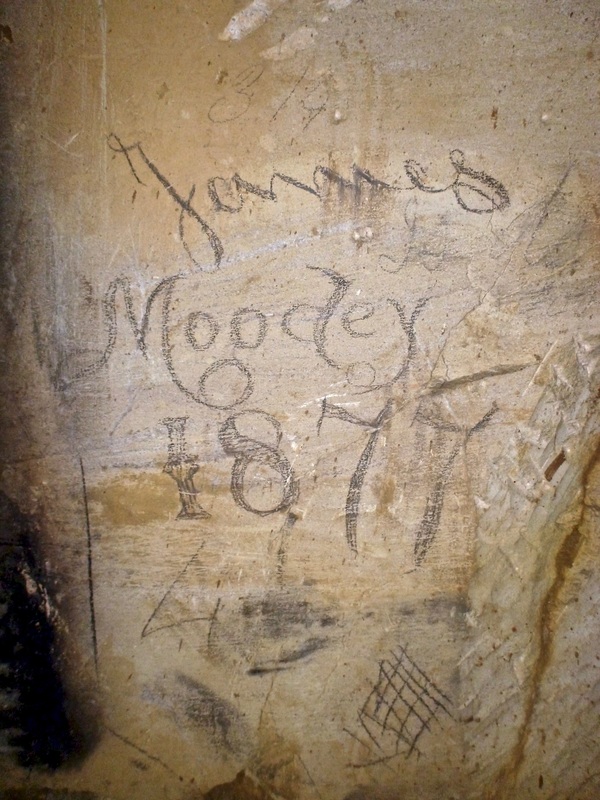

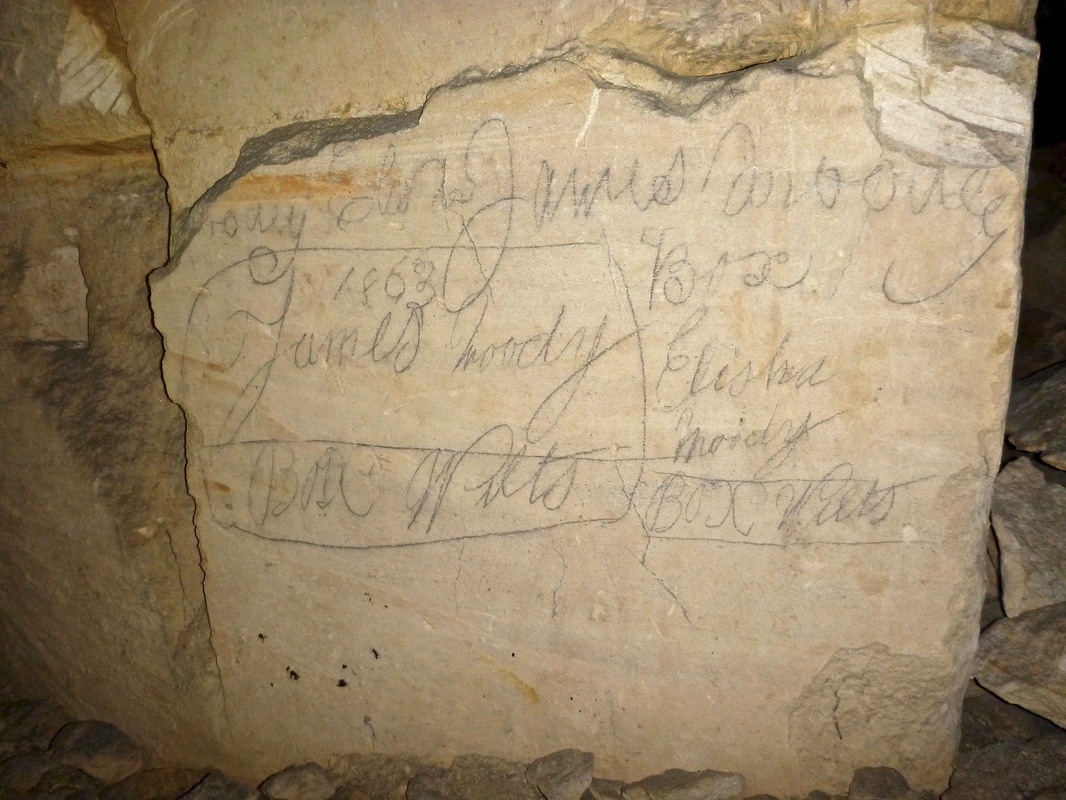

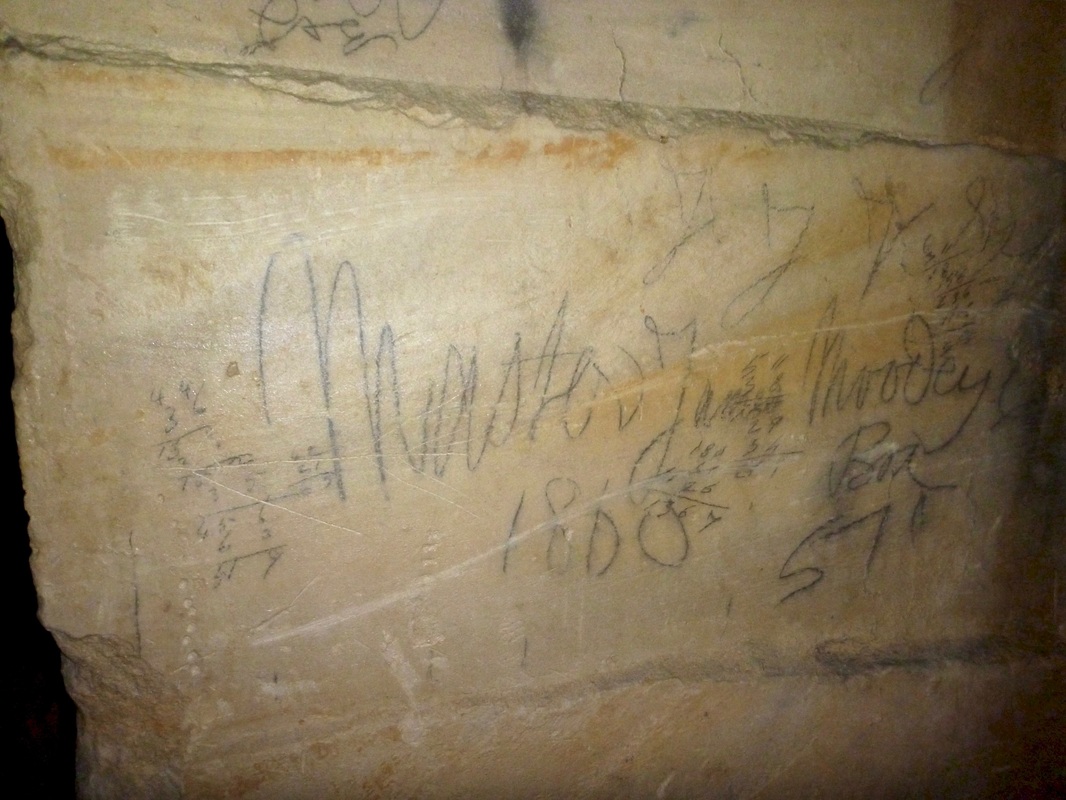

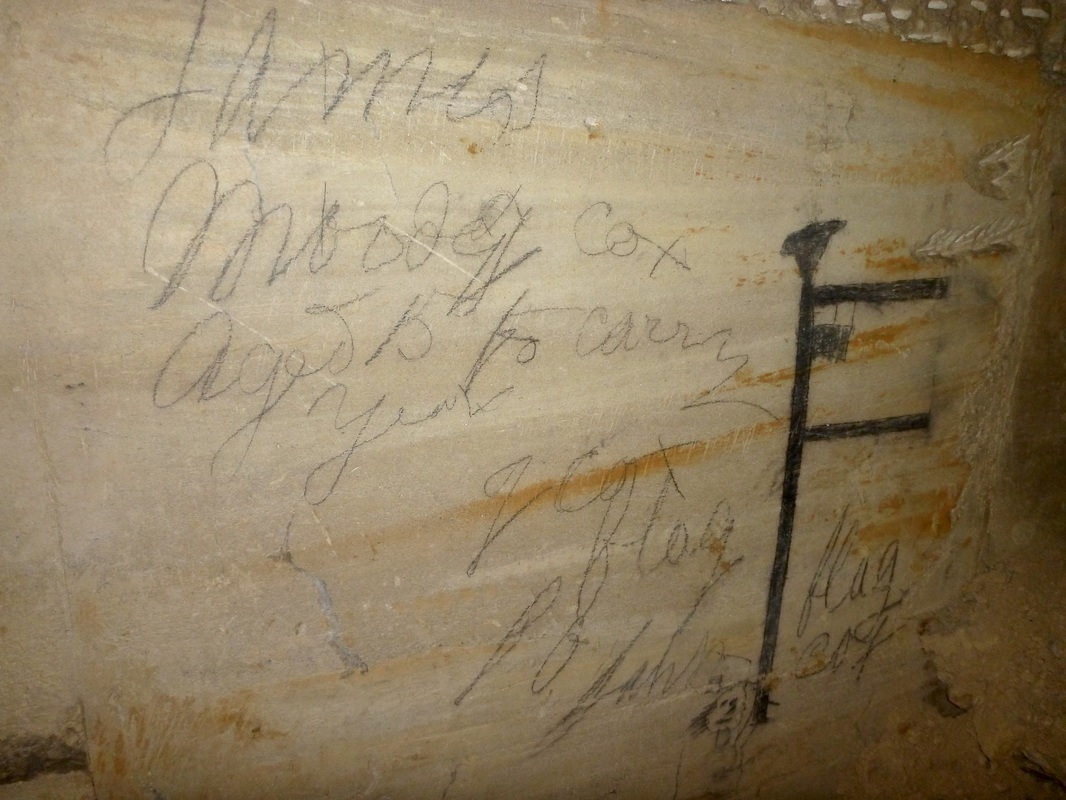

Back to James' story. Around this time, in 1863, when James was 14, we have some graffiti showing James' and Elisha's names together. However, I think the earliest reference to Master James Moodey that I have found in the quarry is in 1860, when James would have been eleven. We also have a reference to James aged 15. I think Cox to carry flag may be unrelated - often graffiti text overlays like this - but I can't be sure.

Marriage

In 1868 James had married a local girl Elizabeth and by 1871 they had a daughter Frances (b 1868) and a son Walter (b 1870). James was by now a skilled stone sawyer and they could afford to rent a small house of their own at Box Hill.

In 1871 Elijah and Mary, now both in their 60s, were living at Townsend Lane, with their grandson Albert Robinson (now a candlemaker aged 19) and four other grandchildren, Annie Hatford and her siblings Tom, Richard and Mary.

In 1868 James had married a local girl Elizabeth and by 1871 they had a daughter Frances (b 1868) and a son Walter (b 1870). James was by now a skilled stone sawyer and they could afford to rent a small house of their own at Box Hill.

In 1871 Elijah and Mary, now both in their 60s, were living at Townsend Lane, with their grandson Albert Robinson (now a candlemaker aged 19) and four other grandchildren, Annie Hatford and her siblings Tom, Richard and Mary.

|

Again we can't absolutely identify the house but the neighbours include many of the people referred to in earlier censuses and it is possible that they always lived in the same property.

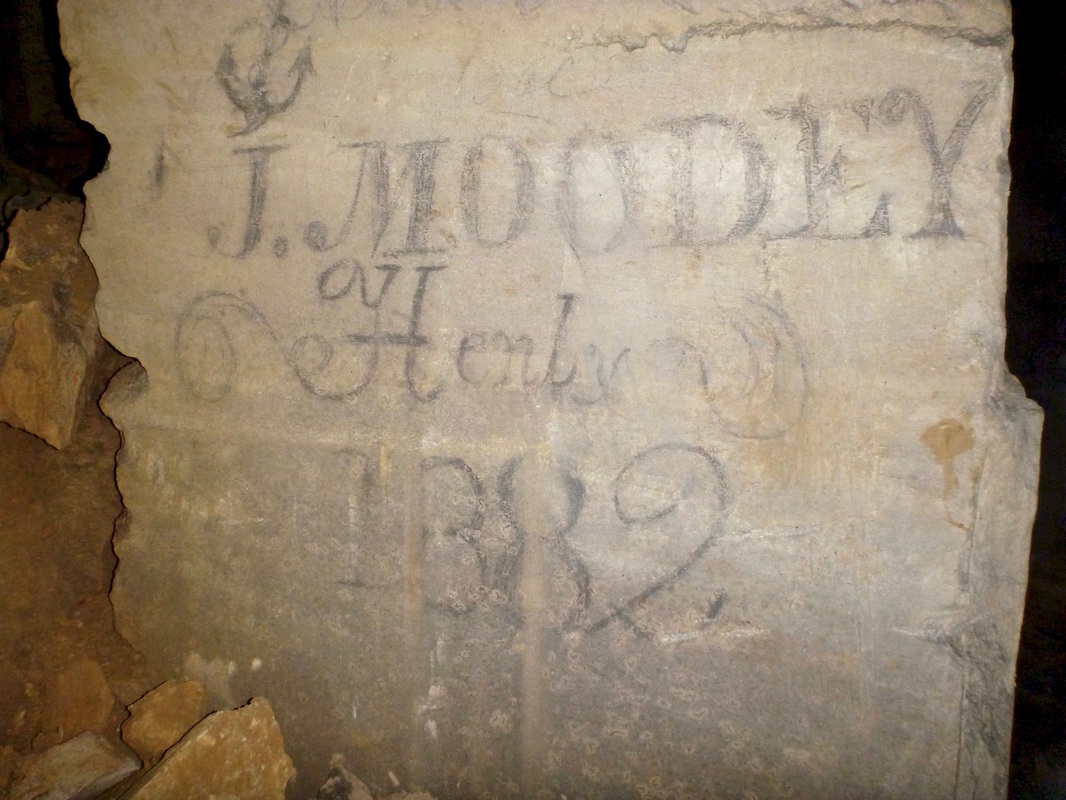

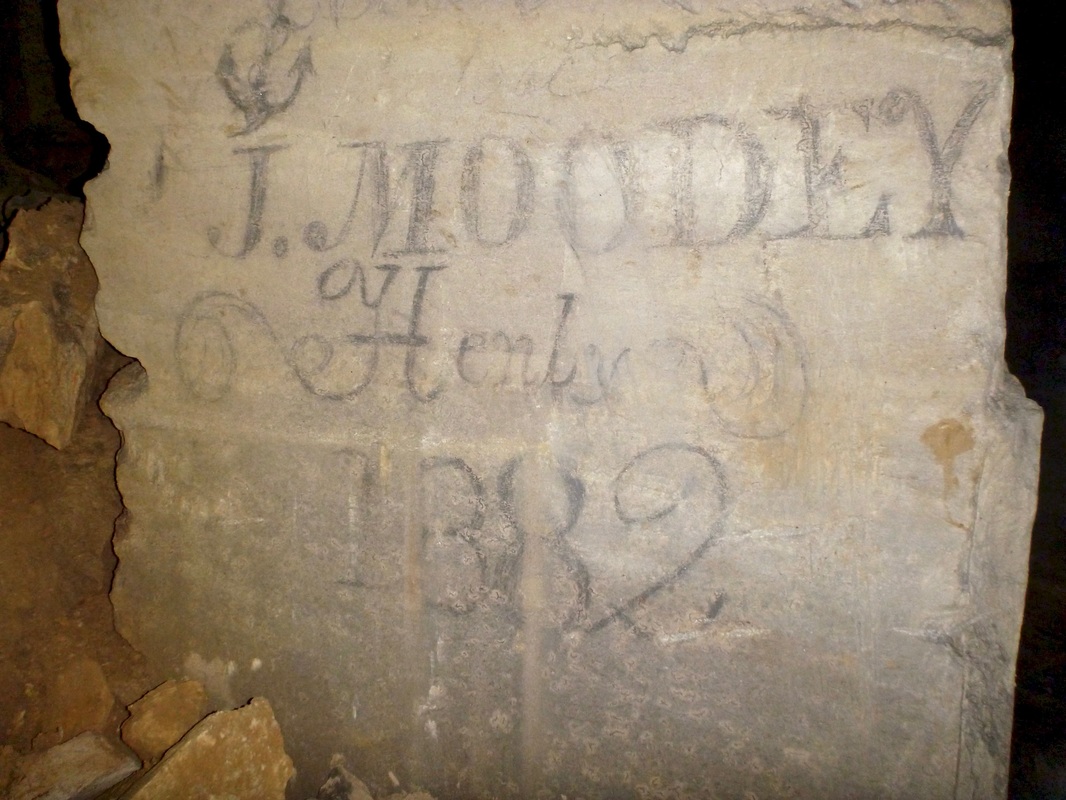

By 1881 James and his family had moved from Box Hill to a house in Henley between Longsplatt and Henley Farm. Again they took in lodgers and John Waldren, labouring quarryman, stayed with them for many years. In 1901 the census gives their address as 6 Henley Cottages. The family of James and Elizabeth continued to grow and in the 1911 census James confirmed that he and Elizabeth had 12 children, of which 11 survived. |

Sankey and Moody

Several of James' underground etchings show the names Moody and Sankey. At first I thought that this was a reference to our Moodey (who changed the spelling) but I found next to nothing for a person called Sankey in the quarry trade.

However, in the wider context of that time there are many references to a duo called Ira Sankey and Dwight L Moody, American evangelists, who sought to proclaim the Gospel of Jesus to the poor and disadvantaged.

Several of James' underground etchings show the names Moody and Sankey. At first I thought that this was a reference to our Moodey (who changed the spelling) but I found next to nothing for a person called Sankey in the quarry trade.

However, in the wider context of that time there are many references to a duo called Ira Sankey and Dwight L Moody, American evangelists, who sought to proclaim the Gospel of Jesus to the poor and disadvantaged.

|

Above: Sankey name dated 1879, and Right: undated after about 1881.

The evangelists were the talk of the age, and their visits widely publicised. Their preaching tours attracted vast audiences and, in equal measure, adoration and disdain. In modern times they are reminiscent of the Billy Graham Crusades of the 1980s. It may be my fancy but I think that James' graffiti gets bigger and bolder at this time; remember too the heavily drawn portrait in the 1880 Moodey and Sankey photograph at the start of the article. |

It is possible (but unproven) that he might have attended a meeting of the evangelists when an excursion was arranged from Bath to hear them speak in 1875.[2] Perhaps he adopted the nickname Sankey or alternatively Moody and Sankey.

|

The Sankey and Moody meetings were extremely lively and, to some minds, very provocative. In 1875 seventy-four Members of Parliament objected to their preaching at Eton College and in 1877 there as talk of a riot at one meeting and the singing of the Moody and Sankey hymn "Hold the Fort".[3] The hymns that the duo collected were compiled into the Sacred Songs and Solos which is still a part of some modern hymn books and revived by some churches.

Possibly James identified himself with Dwight Moody, who used the evangelist practice of inviting his audience to an Altar Call, a commitment to come forward to declare their faith. The practice was widely used by some Methodists groups and would have resonated with the Primitive Methodists of Box who were very evangelical. A description of a meeting at Plymouth in 1882 gives an indication of his evangelist zeal: Mr Moody begged those who wished to become Christians to stand up. One by one, people rose in all parts of the hall ... and an exciting scene ensued, women becoming hysterical and men groaning, praying or crying.[4] |

This may have made James popular with some of his colleagues but annoying to others and his later illustrations show how he fell out with others.

Colleagues

It seems that one of James' mates or co-workers was Daniel Oatley (1841 - 1903). The Oatley family came from a Box stone miner family. Whilst some stayed in the quarrying industry, others, like Daniel's step-brother, Charles Oatley, found other ways to make a living.

Colleagues

It seems that one of James' mates or co-workers was Daniel Oatley (1841 - 1903). The Oatley family came from a Box stone miner family. Whilst some stayed in the quarrying industry, others, like Daniel's step-brother, Charles Oatley, found other ways to make a living.

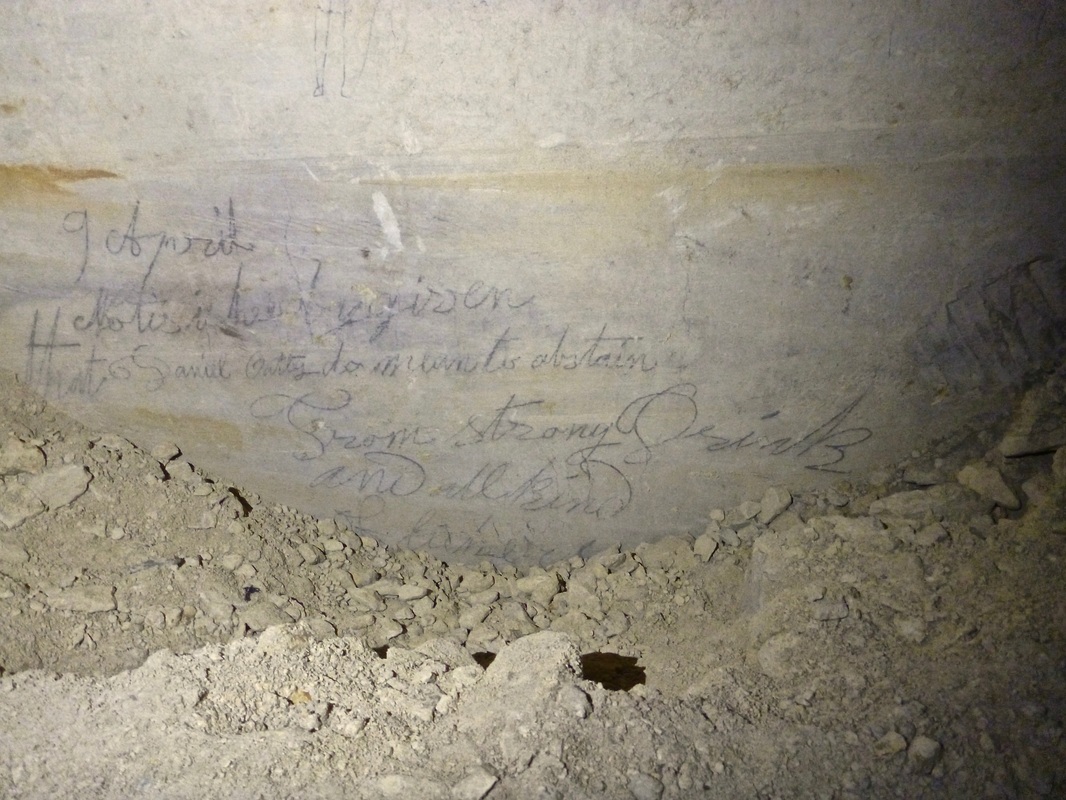

There is a nice reference to Daniel Oatley's pledge to abstinence: 9 April Notice is hereby given that Daniel Oatley do mean to abstain from strong drink and all kind of licker (liquor).

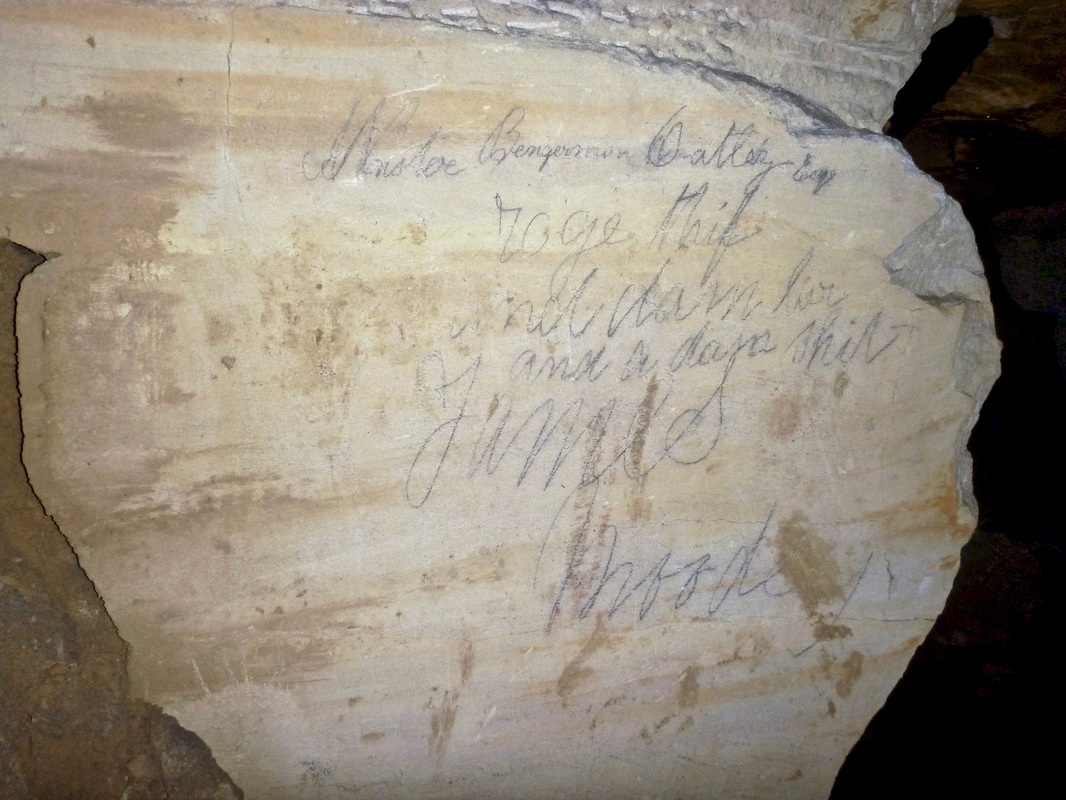

It seems that James was not so fond of Daniel's full brother Benjamin (seen below right with his wife Mary Ann).

It seems that James was not so fond of Daniel's full brother Benjamin (seen below right with his wife Mary Ann).

|

National Events

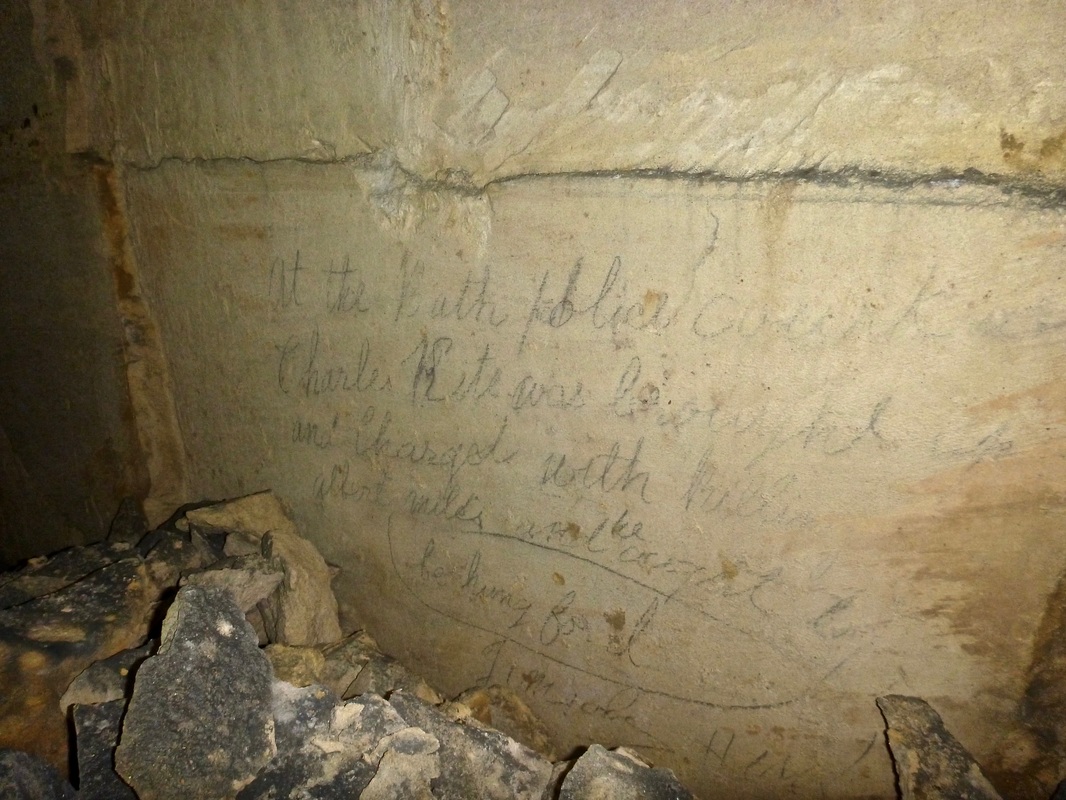

James Moodey and other quarrymen did not just write about themselves and other local characters, occasionally they recorded wider news. This inscription records a murder and subsequent trial in Bath, which occurred in January 1884: At the Bath police court Charles Kite was brought up and charged with killing Albert Miles and be acquit (and) be hung for it. J Moody, Henly (sic). The hanging took place at Taunton Prison on 25 February 1884 and Charles Kite was the last man to be hanged there.[5] While most of the text of this graffiti is recorded in RJ Tucker's book Scripta Legenda, the writer's name is not, which is not surprising as it is relatively indistinct, but it is evident if one is more familiar with James Moodey's writing. |

James and Elizabeth's Family

I haven't been able to find out much about the lives of the next generation and there seems to be no clue in the underground inscriptions. The only person I have been able to trace is James Albert, their middle child. He was recorded as a stone sawyer in the 1891 census and worked for the Lambert Stone Yard at the Railway Station before the Great War. He was referred to in Cecil Lambert's wartime diary. He married Maud and they lived at The Ley in Box until his sudden death on 22 March 1931.[6]

I haven't been able to find out much about the lives of the next generation and there seems to be no clue in the underground inscriptions. The only person I have been able to trace is James Albert, their middle child. He was recorded as a stone sawyer in the 1891 census and worked for the Lambert Stone Yard at the Railway Station before the Great War. He was referred to in Cecil Lambert's wartime diary. He married Maud and they lived at The Ley in Box until his sudden death on 22 March 1931.[6]

Conclusion

The last illustration includes the words James Moody done all this, referring to the strange picture above and a great deal of other artwork that is nearby. It is wrong to read too much into these pictures but some of them show a passion and zeal that must have endeared James to like-minded fellow workers. At the same time, it is possible that others found him a difficult character. Perhaps James needed this aspect of his character to survive what was a deeply demanding job, trapped underground for hours everyday. James passed away in 1912, aged 62.

The last illustration includes the words James Moody done all this, referring to the strange picture above and a great deal of other artwork that is nearby. It is wrong to read too much into these pictures but some of them show a passion and zeal that must have endeared James to like-minded fellow workers. At the same time, it is possible that others found him a difficult character. Perhaps James needed this aspect of his character to survive what was a deeply demanding job, trapped underground for hours everyday. James passed away in 1912, aged 62.

Family Tree

1851 Census

Elijah Moodey (b1811), quarryman, and his wife Mary Ann (b 1812).

Children: Elisha (b 1842); William (b 1844); John (b 1848); Augusta (b 1851).

Lodgers: Elisha Moodey (b 1821), quarryman, Elijah's brother, and his wife Elizabeth (b 1821) with their child James (1849 - 1912). All were born in Combe Down, Somerset.

James Robinson (b 1832 in Yorkshire), stone mason apprentice, and his wife Eliza (b 1833 in Combe Down).

James Moodey

James married Elizabeth in 1868 and they had 12 children, some of whom they called by familial names:

Alice Frances (b 1868); Walter W (b 1870); Florence (sometimes called Adeline) (b 1871); James Albert (1873 - 1931); Arthur E (b 1875); Frederick J (b 1877); Edward George (b 1879); Ernest E (b 1881); Edith M (b 1884); Dora H (b 1885); Flossy S (or Polly) (b 1887); Reginald W (b 1890).

1851 Census

Elijah Moodey (b1811), quarryman, and his wife Mary Ann (b 1812).

Children: Elisha (b 1842); William (b 1844); John (b 1848); Augusta (b 1851).

Lodgers: Elisha Moodey (b 1821), quarryman, Elijah's brother, and his wife Elizabeth (b 1821) with their child James (1849 - 1912). All were born in Combe Down, Somerset.

James Robinson (b 1832 in Yorkshire), stone mason apprentice, and his wife Eliza (b 1833 in Combe Down).

James Moodey

James married Elizabeth in 1868 and they had 12 children, some of whom they called by familial names:

Alice Frances (b 1868); Walter W (b 1870); Florence (sometimes called Adeline) (b 1871); James Albert (1873 - 1931); Arthur E (b 1875); Frederick J (b 1877); Edward George (b 1879); Ernest E (b 1881); Edith M (b 1884); Dora H (b 1885); Flossy S (or Polly) (b 1887); Reginald W (b 1890).

References

[1] It is my conjecture that George is James and Eliza Robinson’s son, given their ages are 19 and 18, although this is not explicitly recorded on the census. George’s relationship to the head of the household (Elijah) is given as Grandson on the handwritten census, so I suspect Eliza is an older daughter of his, or perhaps a niece?

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 20 May 1875 and 27 May 1875

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 24 June 1875 and 11 January 1877

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 5 October 1882

[5] Courtesy http://www.britishexecutions.co.uk/execution-content.php?key=1285

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 26 March 1932

[1] It is my conjecture that George is James and Eliza Robinson’s son, given their ages are 19 and 18, although this is not explicitly recorded on the census. George’s relationship to the head of the household (Elijah) is given as Grandson on the handwritten census, so I suspect Eliza is an older daughter of his, or perhaps a niece?

[2] The Bath Chronicle, 20 May 1875 and 27 May 1875

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 24 June 1875 and 11 January 1877

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 5 October 1882

[5] Courtesy http://www.britishexecutions.co.uk/execution-content.php?key=1285

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 26 March 1932