In Service at Home Alan Payne January 2018

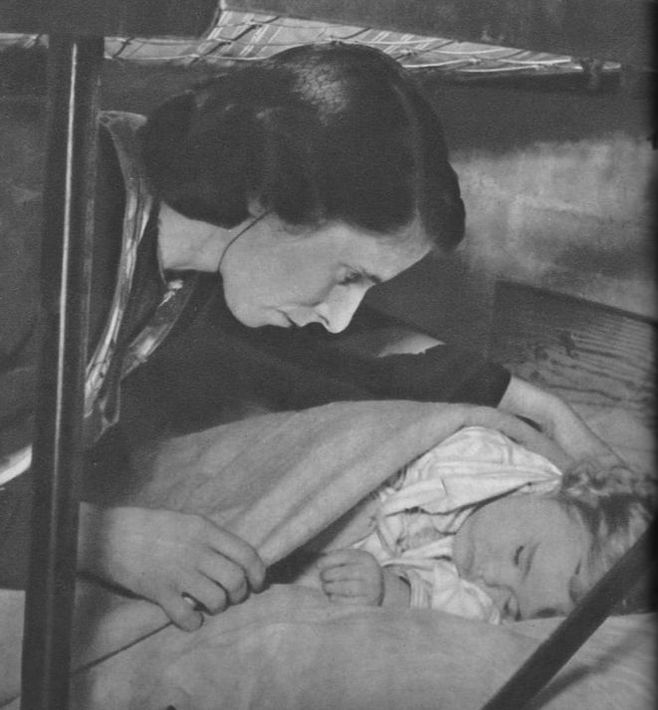

Extracts of Goverment publication The Front LIne 1940-41 , published 1942, showed the increased role of women as Air Raid wardens,

serving meals in Women's Voluntary Service and comforting others in air raid shelters.

serving meals in Women's Voluntary Service and comforting others in air raid shelters.

The presence of uniformed servicemen and women was commonplace throughout the village in wartime, some on leave from active duty overseas, others fulfilling front line duty at home. Many service people, working in military establishments in the area, were billeted with local civilian residents. AOC Alexander Duncan Skrine (Air Officer Commanding, responsible for a whole Group of RAF assets) lived at Heleigh House where, it is reported, the forecourt with its flagpole served as a parade ground.[1]

A succession of military staff were billeted with Philip Martin's parents at 6 Bath Road (now High Street). And so it was throughout the village.

A succession of military staff were billeted with Philip Martin's parents at 6 Bath Road (now High Street). And so it was throughout the village.

|

Areas of Box were taken over for military use and extensively developed. Ashley had a Royal Air Force camp where they worked with live ammunition.[2] Later in the war there was a cinema at the camp every Tuesday night.

Box Rifle Range ran from Doctor's Hill across to the area where Littlemead has now been built. At different times the Rifle Range facility was used by a succession of different services, army, navy and air force and the Home Guard for training whole battalions, as it was one of the few readily available sites in the county. At the end of the war there was even an American radar station at Ashley.[3] Right: Map showing Box Rifle Range (Cecil Lambert courtesy Anna Grayson) |

Box Home Guard

There was also the presence of civilians working in quasi-military roles in civil defence duties. The Home Guard (originally called Local Defence Volunteers) had a specific purpose to delay the advance of any enemy forces which might invade the country. Their work was often menial, such as digging a The People's Moat around Bath.[4] They were always under-staffed and under-resourced, urged on one occasion to bring reaping hooks for duty and an armband for uniforms. But they were the main defence available in Box, controlling the village at the start of the war from their headquarters in the centre of the village.[5]

Air Raid Precaution Wardens

The ARP defended their immediate area against attack from the air either by parachutists or bomb. They enforced the blackout and had an important duty to relay messages of enemy aircraft movements to protect other areas. They were sometimes called The Good Neighbour, responsible for helping people into the nearest shelter on the occasion of an attack.

Colonel Sykes of Ashley Lodge organised lectures about air-raid precautions, and was responsible for the appointment of air-raid wardens.[6] A Rover Scout was stationed at Kingsmoor House to alert residents and the Home Guard of invading parachutists.

Auxiliary Fire Service

The AFS (Auxiliary Fire Service) was a new service started in 1938 to replace the hopelessly antiquated Box Fire Brigade. The service worked at the heart of some of the most dangerous jobs in wartime, dealing with bombing at the centre of air attack and the potential collapse of buildings. In Box the work was different because of its proximity to the Central Ammunitions Depot in the underground quarries. The job of fire protection was too big for the ten men in the local brigade and required considerable military support from the armed services themselves.

In 1938 the Box Brigade was partly disbanded but it was soon realised that the military were more concerned with the quarries than with the houses in Box and its hamlets. So a brigade of ten men led by Mr Abrahams, Box Hill, was reformed in 1940 under the authority of the Rural District Council, who paid for a replacement Beresford Trailer Pump, engine shed and other equipment. The plans for fighting fires were quite basic and each householder was recommended to have a bucket of sand or water readily available.[7] Most of Box's AFS servicemen were unpaid volunteers who put in a night-shift in addition to their everyday job. The area was divided into sections under the control of Mr Chapman-Webb with two wardens on duty in each working shifts either 1pm to 3am or 3am to 7am. Many of them were elderly and unable to continue their work throughout such a long period of war and by 1942 several local men had to resign due to ill-health.[8]

To reduce their autonomy the Bath Ambulance Service was removed from the authority of the independent Fire Brigade and controlled by the Civil Defence Casualty Service, with greater military control in 1941.[9]

There was also the presence of civilians working in quasi-military roles in civil defence duties. The Home Guard (originally called Local Defence Volunteers) had a specific purpose to delay the advance of any enemy forces which might invade the country. Their work was often menial, such as digging a The People's Moat around Bath.[4] They were always under-staffed and under-resourced, urged on one occasion to bring reaping hooks for duty and an armband for uniforms. But they were the main defence available in Box, controlling the village at the start of the war from their headquarters in the centre of the village.[5]

Air Raid Precaution Wardens

The ARP defended their immediate area against attack from the air either by parachutists or bomb. They enforced the blackout and had an important duty to relay messages of enemy aircraft movements to protect other areas. They were sometimes called The Good Neighbour, responsible for helping people into the nearest shelter on the occasion of an attack.

Colonel Sykes of Ashley Lodge organised lectures about air-raid precautions, and was responsible for the appointment of air-raid wardens.[6] A Rover Scout was stationed at Kingsmoor House to alert residents and the Home Guard of invading parachutists.

Auxiliary Fire Service

The AFS (Auxiliary Fire Service) was a new service started in 1938 to replace the hopelessly antiquated Box Fire Brigade. The service worked at the heart of some of the most dangerous jobs in wartime, dealing with bombing at the centre of air attack and the potential collapse of buildings. In Box the work was different because of its proximity to the Central Ammunitions Depot in the underground quarries. The job of fire protection was too big for the ten men in the local brigade and required considerable military support from the armed services themselves.

In 1938 the Box Brigade was partly disbanded but it was soon realised that the military were more concerned with the quarries than with the houses in Box and its hamlets. So a brigade of ten men led by Mr Abrahams, Box Hill, was reformed in 1940 under the authority of the Rural District Council, who paid for a replacement Beresford Trailer Pump, engine shed and other equipment. The plans for fighting fires were quite basic and each householder was recommended to have a bucket of sand or water readily available.[7] Most of Box's AFS servicemen were unpaid volunteers who put in a night-shift in addition to their everyday job. The area was divided into sections under the control of Mr Chapman-Webb with two wardens on duty in each working shifts either 1pm to 3am or 3am to 7am. Many of them were elderly and unable to continue their work throughout such a long period of war and by 1942 several local men had to resign due to ill-health.[8]

To reduce their autonomy the Bath Ambulance Service was removed from the authority of the independent Fire Brigade and controlled by the Civil Defence Casualty Service, with greater military control in 1941.[9]

|

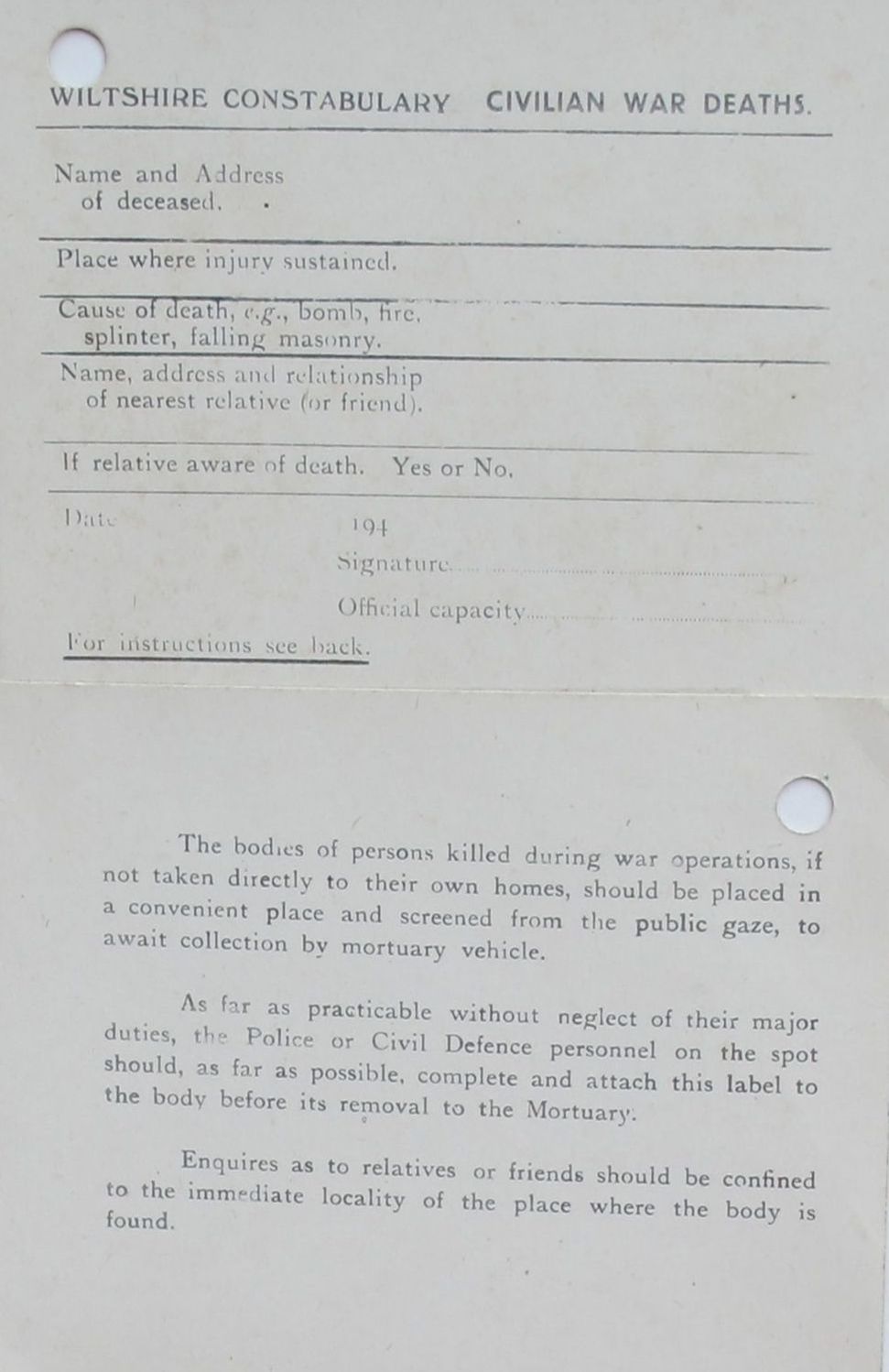

Special Constabulary

The role of the police changed dramatically during the war, mostly to exercise leadership in exceptional incidents such as crowd control, evacuation of areas and civil order where damage threatened theft. They were fully empowered police officers but often only worked part-time and were unpaid. They also monitored the identity of civilians and were expected to recognise most people in their area. Rumours of spies and unusual activities were rife throughout Britain. Several Box residents had reported the possibility of spies being in the village in the years coming up to the war and others told of Fascists living in the area. None of this has been verified but the atmosphere resembles the plot of the wartime movie Went the Day Well? where church wardens turned out to be German spies finally defeated by the ladies of the village. It could have been Box ! St Johns Ambulance As well as their role in accidents and first aid, the Box Brigade had additional responsibility for patrolling the A4. They set up a headquarters roadside tent, replaced in 1940 by a more permanent hut.[10] The hut was in the carpark of the Northey Arms and the dedication of the hut in May 1940 was a grand affair, attended by village notables, a hymn service led by vicar Maltin and an address about the history of St Johns given by Brigadier-General Falkner touching on the Crusading Knights Hospitallers and the story of the order in Tudor times. The curious appearance of the hut symbolised the way that society had accepted military appearance in most civilian activities. |

Role of Women

The role of women in the war was fundamentally different to that in every other preceeding conflict. They were the backbone of everyday existence, providing stability and continuity in the social and economic needs of civilian life, working as ambulance drivers, railway operatives, air raid wardens, first aiders, communications telephonists and providing support where needed. They were involved in most of the services outlined above as well as more unofficial roles through voluntary service.

The Women's Voluntary Service sometimes wore overalls to signify their importance, even though they were a purely voluntary organisation started in 1938. Their main role was to support those in need after disasters: cooking meals for the displaced, settling children in shelters, welcoming evacuees, making, mending and recycling materials. They were The Army Hitler Forgot.

Several local women became nurses through their roles as ambulance drivers and first-aid workers. Some did the formal training of four years, others served in a voluntary capacity. They were needed in Bath, Corsham and in Box where Middlehill House was used as a convalescent hospital for the Canadian Air Force.[11]

By the end of the war the role of women had significantly improved. Pamela Burrow, aged 17½ years, daughter of Mr S Burrow of 2 Elmsleigh Villas, has gained a place in a special school of aircraft design at the Miles Technical Aeronautical College, near Reading.[12] But in many respects the advances made towards equality declined again when peace returned, just as it had after the First World War.

The role of women in the war was fundamentally different to that in every other preceeding conflict. They were the backbone of everyday existence, providing stability and continuity in the social and economic needs of civilian life, working as ambulance drivers, railway operatives, air raid wardens, first aiders, communications telephonists and providing support where needed. They were involved in most of the services outlined above as well as more unofficial roles through voluntary service.

The Women's Voluntary Service sometimes wore overalls to signify their importance, even though they were a purely voluntary organisation started in 1938. Their main role was to support those in need after disasters: cooking meals for the displaced, settling children in shelters, welcoming evacuees, making, mending and recycling materials. They were The Army Hitler Forgot.

Several local women became nurses through their roles as ambulance drivers and first-aid workers. Some did the formal training of four years, others served in a voluntary capacity. They were needed in Bath, Corsham and in Box where Middlehill House was used as a convalescent hospital for the Canadian Air Force.[11]

By the end of the war the role of women had significantly improved. Pamela Burrow, aged 17½ years, daughter of Mr S Burrow of 2 Elmsleigh Villas, has gained a place in a special school of aircraft design at the Miles Technical Aeronautical College, near Reading.[12] But in many respects the advances made towards equality declined again when peace returned, just as it had after the First World War.

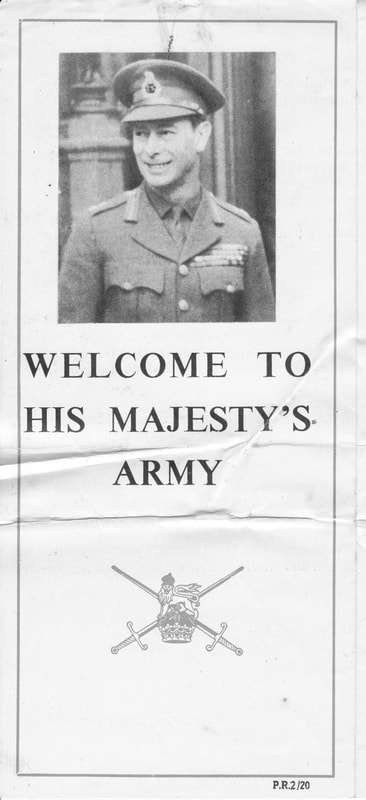

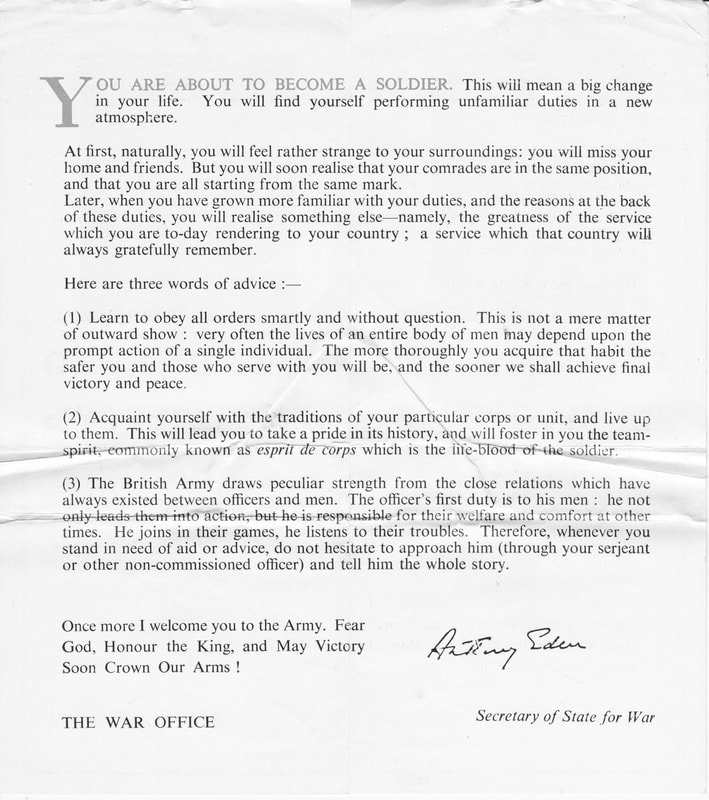

Joining Up

As well as the huge range of civilian duties there was the option of active service, with or without compulsory consciption.

The Great War propoganda of serving King and Country was again employed. The difference probably was the increased commitment to British values after the fascination with our past which had arisen in the 1920s.

As well as the huge range of civilian duties there was the option of active service, with or without compulsory consciption.

The Great War propoganda of serving King and Country was again employed. The difference probably was the increased commitment to British values after the fascination with our past which had arisen in the 1920s.

References

[1] Courtesy David Ibberson

[2] Courtesy Richard Browning

[3] Courtesy Mike Turner

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 June 1940

[5] See full article and diary of Box Home Guard

[6] Claire Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, p.51

[7] Parish Magazine, March 1941

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 3 October 1942

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 11 October 1941

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 18 May 1940

[11] PM Slocombe, Notes in Wiltshire History Centre

[12] Parish Magazine, January 1944

[1] Courtesy David Ibberson

[2] Courtesy Richard Browning

[3] Courtesy Mike Turner

[4] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 20 June 1940

[5] See full article and diary of Box Home Guard

[6] Claire Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, p.51

[7] Parish Magazine, March 1941

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 3 October 1942

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 11 October 1941

[10] The Wiltshire Times, 18 May 1940

[11] PM Slocombe, Notes in Wiltshire History Centre

[12] Parish Magazine, January 1944