|

Improving Life in Box 1918-39 Alan Payne December 2021 Dickens’ shocking novels exposed the worst excesses of poverty which led to reforms in child labour employment. Later there was analysis of living conditions by wealthy liberals in London which led to the formation of the Fabian Society and the development of the Labour Party. Neither initiative produced any meaningful improvement to social conditions in Box. The Great War had exposed many truths about the health and living conditions of ordinary working-class people. After 1918 governments realised that action was needed. But it was not central government initiatives that sparked change but the extension of local authority into most of our everyday social, economic and housing needs. These were new organisations (formed only in the 1890s) and had little experience of managing huge budgets and taking over much of the responsibility for the conditions in which people lived. Right: Quarry Hill in the 1930s showing gas street lighting and homes heated by open coal fires. None of the properties had inside lavatories and most had no internal running water. (Photo courtesy John Brooke Flashman) |

Housing Conditions in Box

In December 1920, the Chippenham (Rural) Housing Scheme announced the result of their review of housing in the district and advocated the building of 120 new cottages, including 36 properties at Box.[1] It wasn’t simply overcrowding and the need for more accommodation in the area, the quality of properties was simply inadequate; most of the cottages in the hamlets lacked domestic plumbing and internal sewage pipes. Earth closets or pail toilets (often a row of facilities in an outbuilding) were the norm at Mill Lane, Townsend and other central locations, even in Box Schools in the early years of the twentieth century.

In December 1920, the Chippenham (Rural) Housing Scheme announced the result of their review of housing in the district and advocated the building of 120 new cottages, including 36 properties at Box.[1] It wasn’t simply overcrowding and the need for more accommodation in the area, the quality of properties was simply inadequate; most of the cottages in the hamlets lacked domestic plumbing and internal sewage pipes. Earth closets or pail toilets (often a row of facilities in an outbuilding) were the norm at Mill Lane, Townsend and other central locations, even in Box Schools in the early years of the twentieth century.

There were repeated instances of infectious disease reported in Box in the years 1918 to 1939: scarlet fever (1921), 16 cases of chicken pox (1925), 3 cases of scarlatina (1925), diphtheria (1931) and tuberculosis (1931) in Box.[2] Some were caused by inadequate and overcrowded housing. These problems weren't limited to Box and the Chippenham District Council proposed 32 new properties in Corsham and 20 in Lacock.[3] In the early years after the war, there was a general upsurge in the building trade to replace slum dwellings but the Box stone firms were unable to take advantage. The cost of extracting what remained of local building stone was significantly higher than making bricks or concrete blocks. In 1928 an emergency meeting of the Chippenham District Council agreed to subsidise new Box council houses by £7.10s above the contract price to enable them to be built of local materials.[4]

It wasn’t just the dampness and over-crowding which caused these problems; there was also heating, cooking and interior water supplies to be considered. In October 1931 the ten tenants of the new council houses at The Ley requested that the District Housing Committee install a gas stove in their scullery to replace a range in the living room (refused).[5]

Water Supplies

The provision of water was a greater problem, especially in the endless drought of 1921 when authorities suggested limiting bath water to 1 inch. Private supplies were cut off without prior notification drawing complaints from the residents of Box Hill.[6] A special committee was appointed by the District Council that year which recommended a well be sunk at Washwells and the water piped into the village at a cost of £18,550.[7] It wasn’t adequate and the Northey Estate offered their water supply at a cost of £5,700 but, even then, supplies to Box Hill and the area of Blue Vein Farm were not covered. A special meeting of Box parish residents was held in the Schools to discuss the issue in February 1921.[8] It was proposed to increase rates by 10% to pay for the scheme (approved to purchase the Northey supply but to defer the distribution scheme).[9] But no scheme covered all the hamlets for which water was supplied by different owners including Lord Islington at Rudloe.

In the event, the scheme didn’t solve all problems and 60 Box ratepayers signed a petition complaining about increased water charges in 1925.[10] The issues rumbled on. A shortage of water in Ashley in 1926 was said to be due to leakages and supplies to Totney, Wormcliffe and outlying Kingsdown areas only came up for further discussion in 1928.[11] A windmill and pump was suggested to repair the Ditteridge water supply in 1928.[12] In the end, the issue of inadequate supply was solved by a magnificent gift by Sir Felix Brunner of Rudloe Farm (now called Rudloe Manor) in 1929.[13] He donated the water supply from Hungerford Wood, Widdenham, to Pickwick and Box, piped through Brewers Yard, Box Hill. The amount allocated to Box was 50,000 gallons in addition to the existing 25,000 gallons from the Northey purchase. New steel tank reservoirs were proposed for Box and Kingsdown connecting with a pumping station at Washwells. The cost of the pipework and reservoirs was estimated to be £12,100 for Box to be paid for out of the rates for the next 30 years. The cost of the connection was spread over the entire parish, even those who had their own private supply such as at the children’s Holy Innocents’ Home at Sunnyside which ran dry in 1933, causing the home to apply to be admitted to the main grid.[14] A chlorinator was only installed in the main Box water supply after 1939.[15] Sewage works took even longer to fix and sewage pipes weren’t laid into The Ley until after 1928.[16]

Refuse Collection

Refuse collection was another difficult subject as the village was so spread out. The Rural District Council and the Sanitary Inspector had recommended a regular removal of household refuse in Box in 1914 but the parish council objected to the idea on grounds of cost and the absence of high death rates or the prevalence of zymotic disease (fermenting refuse).[17] Instead of a council collection, the parish proposed to introduce a scavenging scheme, offering a fixed fee contract to those who wished to tender for the work. In 1923 tenders were invited for the refuse collection contract which was awarded to G Bradfield for £10 for clearing Ashley and £20 for Box.[18] It was undervalued and in 1925 H Sheppard was awarded the Ashley and Kingsdown areas for a price of £6.10s for each place and the rest of Box went to G Bradfield for £25.[19]

It wasn’t just the dampness and over-crowding which caused these problems; there was also heating, cooking and interior water supplies to be considered. In October 1931 the ten tenants of the new council houses at The Ley requested that the District Housing Committee install a gas stove in their scullery to replace a range in the living room (refused).[5]

Water Supplies

The provision of water was a greater problem, especially in the endless drought of 1921 when authorities suggested limiting bath water to 1 inch. Private supplies were cut off without prior notification drawing complaints from the residents of Box Hill.[6] A special committee was appointed by the District Council that year which recommended a well be sunk at Washwells and the water piped into the village at a cost of £18,550.[7] It wasn’t adequate and the Northey Estate offered their water supply at a cost of £5,700 but, even then, supplies to Box Hill and the area of Blue Vein Farm were not covered. A special meeting of Box parish residents was held in the Schools to discuss the issue in February 1921.[8] It was proposed to increase rates by 10% to pay for the scheme (approved to purchase the Northey supply but to defer the distribution scheme).[9] But no scheme covered all the hamlets for which water was supplied by different owners including Lord Islington at Rudloe.

In the event, the scheme didn’t solve all problems and 60 Box ratepayers signed a petition complaining about increased water charges in 1925.[10] The issues rumbled on. A shortage of water in Ashley in 1926 was said to be due to leakages and supplies to Totney, Wormcliffe and outlying Kingsdown areas only came up for further discussion in 1928.[11] A windmill and pump was suggested to repair the Ditteridge water supply in 1928.[12] In the end, the issue of inadequate supply was solved by a magnificent gift by Sir Felix Brunner of Rudloe Farm (now called Rudloe Manor) in 1929.[13] He donated the water supply from Hungerford Wood, Widdenham, to Pickwick and Box, piped through Brewers Yard, Box Hill. The amount allocated to Box was 50,000 gallons in addition to the existing 25,000 gallons from the Northey purchase. New steel tank reservoirs were proposed for Box and Kingsdown connecting with a pumping station at Washwells. The cost of the pipework and reservoirs was estimated to be £12,100 for Box to be paid for out of the rates for the next 30 years. The cost of the connection was spread over the entire parish, even those who had their own private supply such as at the children’s Holy Innocents’ Home at Sunnyside which ran dry in 1933, causing the home to apply to be admitted to the main grid.[14] A chlorinator was only installed in the main Box water supply after 1939.[15] Sewage works took even longer to fix and sewage pipes weren’t laid into The Ley until after 1928.[16]

Refuse Collection

Refuse collection was another difficult subject as the village was so spread out. The Rural District Council and the Sanitary Inspector had recommended a regular removal of household refuse in Box in 1914 but the parish council objected to the idea on grounds of cost and the absence of high death rates or the prevalence of zymotic disease (fermenting refuse).[17] Instead of a council collection, the parish proposed to introduce a scavenging scheme, offering a fixed fee contract to those who wished to tender for the work. In 1923 tenders were invited for the refuse collection contract which was awarded to G Bradfield for £10 for clearing Ashley and £20 for Box.[18] It was undervalued and in 1925 H Sheppard was awarded the Ashley and Kingsdown areas for a price of £6.10s for each place and the rest of Box went to G Bradfield for £25.[19]

Sewerage Work

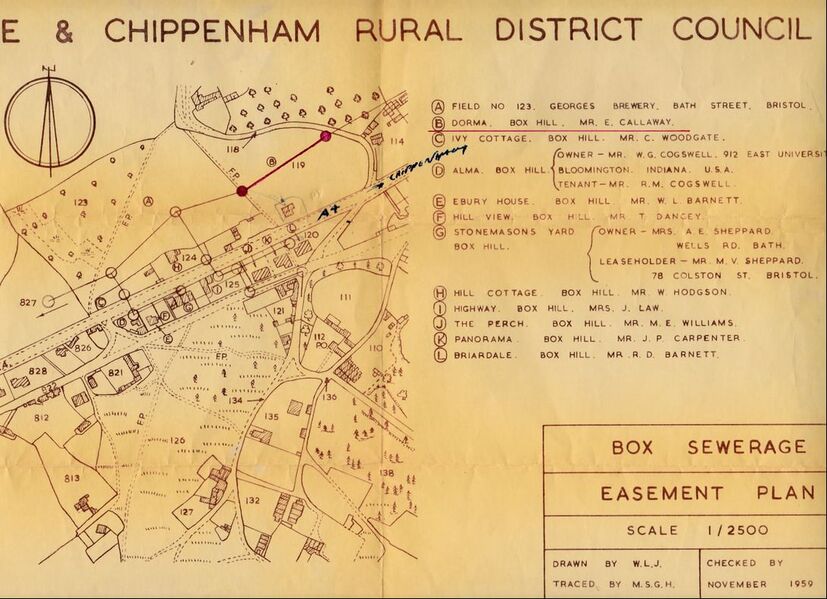

Arguably it was the condition of sewage facilities in the village that was the main cause of disease. The rural nature of the village area and the ribbon development meant a very high cost of treatment and disposal. A later review of costs highlighted the problem in 1956 when the price of sewerage installation for Box was estimated as £108,250 (today nearly £3 million).[20] The effluent as (currently) discharged into Box Brook was little better than crude sewage. Work was particularly needed in Box village, Box Hill, Ashley, Kingsdown, Henley, Middlehill and Ditteridge - in other words, everywhere. Even then, some isolated houses could not be drained economically and many outlying properties still have septic tanks instead of mains sewage facilities.

Arguably it was the condition of sewage facilities in the village that was the main cause of disease. The rural nature of the village area and the ribbon development meant a very high cost of treatment and disposal. A later review of costs highlighted the problem in 1956 when the price of sewerage installation for Box was estimated as £108,250 (today nearly £3 million).[20] The effluent as (currently) discharged into Box Brook was little better than crude sewage. Work was particularly needed in Box village, Box Hill, Ashley, Kingsdown, Henley, Middlehill and Ditteridge - in other words, everywhere. Even then, some isolated houses could not be drained economically and many outlying properties still have septic tanks instead of mains sewage facilities.

Fire Protection

Part of the council’s remit was to ensure adequate fire protection which was deemed to be inadequate in the village, manned by the people shown above in 1913. As a result, the council made a donation of £50 towards the cost of a new, steam-driven fire engine in the Chippenham District in 1922.[21] It was claimed that the engine would be in Box within 20 minutes as needed whether day or night.

Hospital Facilities

The provision of hospital support was dramatically different before the Second World War with individual donations supporting primary health care before the National Health Service. In 1937 a large article in local newspapers demonstrated the way that the system functioned claiming: The public love the voluntary hospital system and wanted to maintain it; they did not want State-aided hospitals.[22] The scheme was based on collecting boxes around the RUH area run by employers, shopkeepers and individuals and the total donated to the Royal United Hospitals from all sources came to £10,489. It was up year-on-year and the newspaper celebrated a successful year.

The sums involved were trivial, however, as the report shows: £7,800 to the hospital which supported 45 of the 192 beds there, £172.15s.2d to ambulance service, £23.19s.3d to convalescent homes and £274.0s.5d to opticians. The amounts donated for individual districts reflected the wealth of the area with Box District donating £272.10s.10d (today worth £20,000). We can see in retrospect how the costs of treatment and equipment in the modern health service dwarf these sums and the rapidly approaching realisation that an entirely new system was needed.

Part of the council’s remit was to ensure adequate fire protection which was deemed to be inadequate in the village, manned by the people shown above in 1913. As a result, the council made a donation of £50 towards the cost of a new, steam-driven fire engine in the Chippenham District in 1922.[21] It was claimed that the engine would be in Box within 20 minutes as needed whether day or night.

Hospital Facilities

The provision of hospital support was dramatically different before the Second World War with individual donations supporting primary health care before the National Health Service. In 1937 a large article in local newspapers demonstrated the way that the system functioned claiming: The public love the voluntary hospital system and wanted to maintain it; they did not want State-aided hospitals.[22] The scheme was based on collecting boxes around the RUH area run by employers, shopkeepers and individuals and the total donated to the Royal United Hospitals from all sources came to £10,489. It was up year-on-year and the newspaper celebrated a successful year.

The sums involved were trivial, however, as the report shows: £7,800 to the hospital which supported 45 of the 192 beds there, £172.15s.2d to ambulance service, £23.19s.3d to convalescent homes and £274.0s.5d to opticians. The amounts donated for individual districts reflected the wealth of the area with Box District donating £272.10s.10d (today worth £20,000). We can see in retrospect how the costs of treatment and equipment in the modern health service dwarf these sums and the rapidly approaching realisation that an entirely new system was needed.

The changes effected by war and these measures re-shaped the role of government and centralised responsibility for most Box residents in ways which earlier generations would have thought impossible and intrusive. They were just in time to provide better accommodation for the new influx of newcomers to the village because of the Second World War.

References

[1] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 4 December 1920

[2] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 March 1921, 28 March 1925 and 5 December 1925 and North Wilts Herald,

7 August 1931

[3] Western Gazette, 3 September 1920

[4] North Wilts Herald, 18 May 1928

[5] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 3 October 1931

[6] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 1 May 1920

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 August 1920

[8] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 February 1921

[9] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 March 1921

[10] North Wilts Herald, 22 May 1925

[11] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 11 September 1926 and 19 May 1928

[12] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 22 December 1928

[13] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 June 1929

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 25 November 1933

[15] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 11 February 1939

[16] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 May 1928

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 16 March 1916

[18] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 10 November 1923

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 December 1925

[20] The Wiltshire Times, 21 January 1956

[21] The Wiltshire Times, 5 August 1922

[22] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 March 1938

[1] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 4 December 1920

[2] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 March 1921, 28 March 1925 and 5 December 1925 and North Wilts Herald,

7 August 1931

[3] Western Gazette, 3 September 1920

[4] North Wilts Herald, 18 May 1928

[5] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 3 October 1931

[6] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 1 May 1920

[7] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 24 August 1920

[8] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 February 1921

[9] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 March 1921

[10] North Wilts Herald, 22 May 1925

[11] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 11 September 1926 and 19 May 1928

[12] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 22 December 1928

[13] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 June 1929

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 25 November 1933

[15] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 11 February 1939

[16] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 May 1928

[17] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 16 March 1916

[18] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 10 November 1923

[19] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 5 December 1925

[20] The Wiltshire Times, 21 January 1956

[21] The Wiltshire Times, 5 August 1922

[22] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 March 1938