|

Impact of the Railways on Box

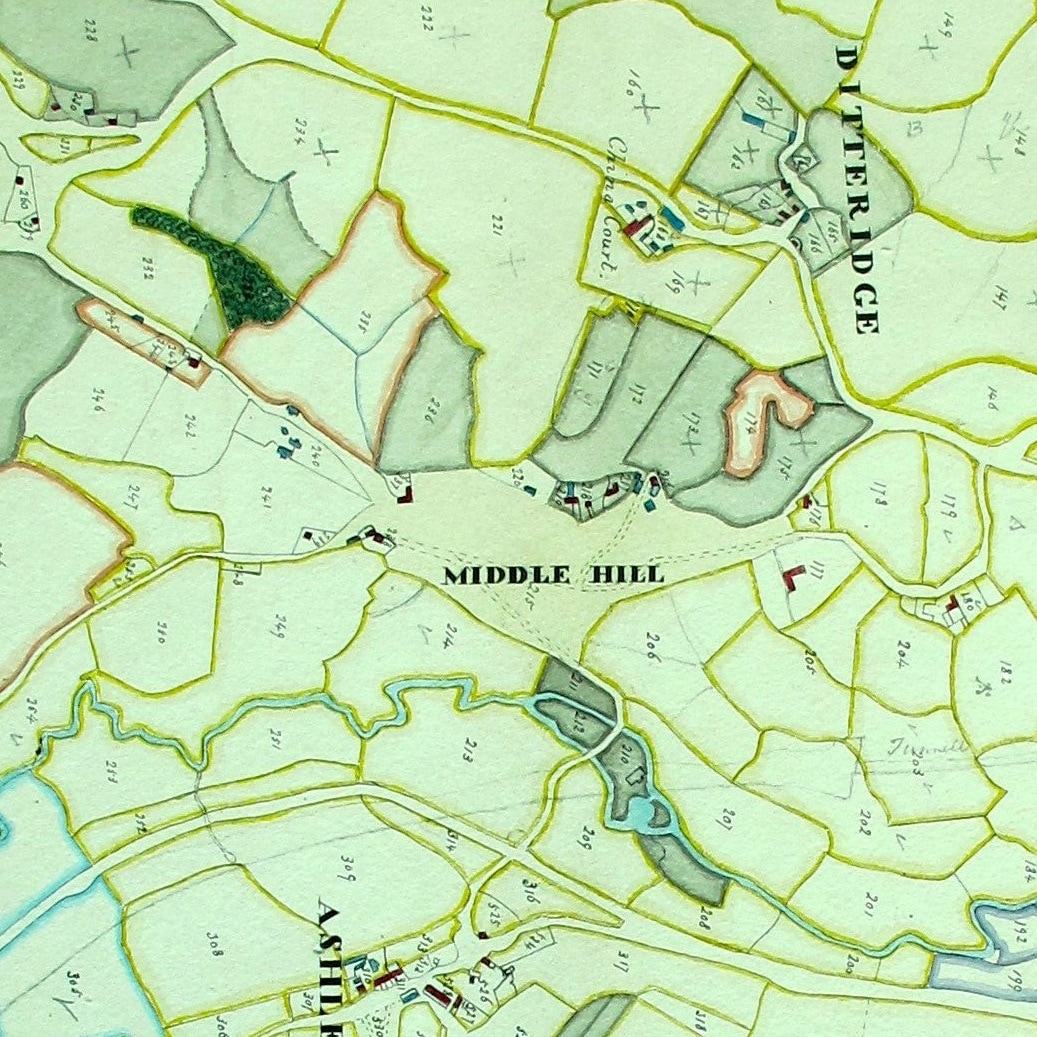

Alan Payne July 2017 Railways altered life in Britain beyond recognition for earlier generations. It also altered the infrastructure and look of Box village. The advent of the railway caused the destruction of some buildings and the creation of several new roads. It was built by compulsory purchase of land from existing owners, much of it in the possession of the Northey family, particularly around the area of Box Station in Ashley. It caused the destruction of some areas of great historic interest such as the historic Cuttings Mill, demolished to build the railway line near Box Station.[1] Right: The route of the railway through Middlehill Tunnel drawn in pencil before the building of The Avenue road accessing Middlehill but after the building of the A4. (Courtesy Wiltshire History Centre) |

Social Impact of Railways

The industrial revolution in Britain was based on coal brought by railways for manufacturing, transport and domestic use. If you have a Victorian house, you will often have small bedroom fireplaces only suitable for burning coal, which differentiate domestic life after the advent of railways with upstairs room heating. The railways affected every person in Britain, perhaps the most universal technological development ever. It was an agent of social change which Parliament deliberately promoted in 1844 requiring at least one service every day on every railway line priced at 1d per mile to extend the provision of travel to less affluent people in Britain.

The changes that the railways brought were demonstrated in the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 with many modern conveniences that we are accustomed to: water closets for indoor lavatory use (public lavatories charging a penny for a private cubicle), hot water in bathrooms, caste-iron goods including a piano frame, and a host of manufactured goods including glass daguerreotypes (an early photographic method).

The industrial revolution in Britain was based on coal brought by railways for manufacturing, transport and domestic use. If you have a Victorian house, you will often have small bedroom fireplaces only suitable for burning coal, which differentiate domestic life after the advent of railways with upstairs room heating. The railways affected every person in Britain, perhaps the most universal technological development ever. It was an agent of social change which Parliament deliberately promoted in 1844 requiring at least one service every day on every railway line priced at 1d per mile to extend the provision of travel to less affluent people in Britain.

The changes that the railways brought were demonstrated in the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 with many modern conveniences that we are accustomed to: water closets for indoor lavatory use (public lavatories charging a penny for a private cubicle), hot water in bathrooms, caste-iron goods including a piano frame, and a host of manufactured goods including glass daguerreotypes (an early photographic method).

|

New Roads

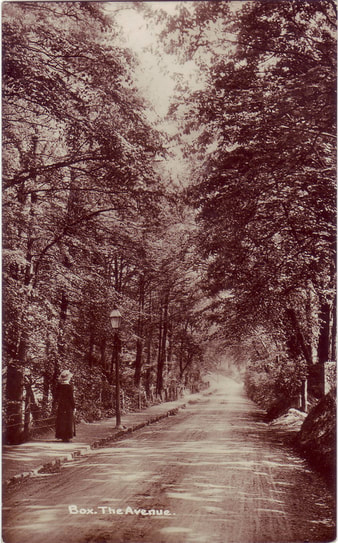

The railway line totally altered the road system at Ashley. A new dog-leg road was built from the old turnpike road at the point where the A4 and Ashley Lane meet (now a petrol garage). The new road carried on to Box Railway Station and then looped back to the old turnpike road at Shockerwick. The route of this road was established before the railway was built but The Avenue and the bridge over the Brook were constructed by the railway to replace the road that had formerly crossed the site and close to Cutting's Mill. The Avenue was constructed from the railway station up to Middlehill. It was built as a promenade for the convenience of passengers accessing the railway facilities, tree-lined and with a pavement. An early postcard (right, courtesy Box Parish Council) shows how attractive the road was. Even the height of the old High Street through the centre of the village was altered for the convenience of the the railway station and its traffic in hauling stone from Box Station to other parts of Britain. For the easier passage of stone carts, Brunel lowered the road outside The Hermitage, where the old level can still be seen on the wall.[2] |

In the centre of the village, the road was raised in height at the site where the Co-op (now McColls) stands to reduce the speed at which stone carts came down Box Hill.

Time in Box

The railway caused a major alteration in the way time was reckoned. For centuries it had not mattered and approximate local time or time of the day (dawn, sunset and noon) was all that was needed until the railways arrived. The first published timetable was on the London and Birmingham line in 1838 with multiple times for arrival and departure, which, for example, showed the time that trains arrived in at a station from London, local time and the time relevant for people coming from the end of the line.

The time difference between Bath and London was about 10 minutes and in the 1840s GWR published a timetable reporting arrivals and departures in local times and a separate column showing times for local and major towns en route. Bradshaw's guides, first published in 1842, altered all that by publishing timetables for travellers. This wasn't the whole story, however, and there were still many differences between times announced with newspaper timetables, Bradshaw and GWR timetables often saying something different. It was impossible to understand and London time, called Greenwich Mean Time, was adopted across the whole country.

The railway caused a major alteration in the way time was reckoned. For centuries it had not mattered and approximate local time or time of the day (dawn, sunset and noon) was all that was needed until the railways arrived. The first published timetable was on the London and Birmingham line in 1838 with multiple times for arrival and departure, which, for example, showed the time that trains arrived in at a station from London, local time and the time relevant for people coming from the end of the line.

The time difference between Bath and London was about 10 minutes and in the 1840s GWR published a timetable reporting arrivals and departures in local times and a separate column showing times for local and major towns en route. Bradshaw's guides, first published in 1842, altered all that by publishing timetables for travellers. This wasn't the whole story, however, and there were still many differences between times announced with newspaper timetables, Bradshaw and GWR timetables often saying something different. It was impossible to understand and London time, called Greenwich Mean Time, was adopted across the whole country.

New Hamlets Built

A new industrial community grew in mid Victorian Box on land which had previously been fields and wasteland. For five years from 1836 to 1841, Box was invaded by an army of railway construction workers, navigators (navvies or itinerant labourers) armed with pickaxe and shovels, working and living in gangs, tunnelling underground through Box Hill. They were paid high wages for a highly dangerous job. Many were unmarried men, some living in central Box but many sleeping in temporary accommodation on Box Hill and Quarry Hill in shanty towns of wooden huts or in a large hut sleeping thirty to a room in tiers of bunks.[3]

From these shanty buildings the hamlets of Box Hill and Quarry Hill developed into the self-contained communities and historic stone houses that we enjoy today. Without the railway and the stone workings it is questionable whether we would have had the public houses built to service the workmen's needs, the Quarryman's Arms, the Rising Sun and Tunnel Inn. Nor would the several Methodist Chapels in the area have been needed.

A new industrial community grew in mid Victorian Box on land which had previously been fields and wasteland. For five years from 1836 to 1841, Box was invaded by an army of railway construction workers, navigators (navvies or itinerant labourers) armed with pickaxe and shovels, working and living in gangs, tunnelling underground through Box Hill. They were paid high wages for a highly dangerous job. Many were unmarried men, some living in central Box but many sleeping in temporary accommodation on Box Hill and Quarry Hill in shanty towns of wooden huts or in a large hut sleeping thirty to a room in tiers of bunks.[3]

From these shanty buildings the hamlets of Box Hill and Quarry Hill developed into the self-contained communities and historic stone houses that we enjoy today. Without the railway and the stone workings it is questionable whether we would have had the public houses built to service the workmen's needs, the Quarryman's Arms, the Rising Sun and Tunnel Inn. Nor would the several Methodist Chapels in the area have been needed.

Haulage

Before the coming of the railways there were numerous freight firms bringing goods to Box by stage coach, horse and cart, and packhorse. Most light-weight, high-value goods came on the turnpike roads which ran either through Kingsdown or from Corsham, bringing news, parcels and domestic commodities such as needles, teapots and linen. Heavy goods, including coal, came by the Somerset Coal Canal and the Kennett and Avon waterways.

The wars with Napoleon threatened routes at sea and raised fears of invasion. It highlighted the unpredictability of road and sea haulage in times of disruption and adverse weather.[4] By contrast, the railways ran to preset times throughout the year, offering reliability and certainty to seller, purchaser and those insuring the items. The railway freight covered all types of goods of different shapes and weights.

The directors of GWR promoted the use of the railways for bulk goods from the outset of the line in 1842: In stone and coal , two articles of considerable extent in trade, notwithstanding the general depression in the trade of the country.[5] The annual report of that year went on, The Directors are also about to send coal to their principal country stations for sale, with a view to encourage that traffic of the line.

But above all it was the cheapness of the railways that altered Box's economy. It has been calculated that the freight rates per ton in 1865 was one-twentieth of the rate in 1700.[7] It was this economic factor that enabled the growth of Box village as a producer of stone, candles, flour and other goods for dispatch throughout Britain.

Before the coming of the railways there were numerous freight firms bringing goods to Box by stage coach, horse and cart, and packhorse. Most light-weight, high-value goods came on the turnpike roads which ran either through Kingsdown or from Corsham, bringing news, parcels and domestic commodities such as needles, teapots and linen. Heavy goods, including coal, came by the Somerset Coal Canal and the Kennett and Avon waterways.

The wars with Napoleon threatened routes at sea and raised fears of invasion. It highlighted the unpredictability of road and sea haulage in times of disruption and adverse weather.[4] By contrast, the railways ran to preset times throughout the year, offering reliability and certainty to seller, purchaser and those insuring the items. The railway freight covered all types of goods of different shapes and weights.

The directors of GWR promoted the use of the railways for bulk goods from the outset of the line in 1842: In stone and coal , two articles of considerable extent in trade, notwithstanding the general depression in the trade of the country.[5] The annual report of that year went on, The Directors are also about to send coal to their principal country stations for sale, with a view to encourage that traffic of the line.

But above all it was the cheapness of the railways that altered Box's economy. It has been calculated that the freight rates per ton in 1865 was one-twentieth of the rate in 1700.[7] It was this economic factor that enabled the growth of Box village as a producer of stone, candles, flour and other goods for dispatch throughout Britain.

References

[1] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[2] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.37

[3] Hibbert, Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, p.646

[4] GL Turnball, Scotch Linen, Storms, Wars and Privateers published in Road Transport in the Horse-Drawn Era, Editor Dorian Gerhold, 1996, Scholar Press, p.75

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 25 August 1842

[6] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.80

[7] Dan Bogart, The Transport Revolution in Industrialising Britain, [email protected]

[1] John Froud, Box Station, Special GWR Edition No 2, p.133

[2] Clare Higgens, Box Wiltshire an Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.37

[3] Hibbert, Christopher Hibbert, The English: A Social History 1066-1945, p.646

[4] GL Turnball, Scotch Linen, Storms, Wars and Privateers published in Road Transport in the Horse-Drawn Era, Editor Dorian Gerhold, 1996, Scholar Press, p.75

[5] The Bath Chronicle, 25 August 1842

[6] Colin G Maggs, The GWR Swindon to Bath Line, p.80

[7] Dan Bogart, The Transport Revolution in Industrialising Britain, [email protected]