|

Horatio Lewis Orton Suggested and photos by Professor Yota Dimitriadi Research by Martin Stower and Jean Coburn March 2023 We received a request for information from Professor Yota Dimitriadi of Reading University about a fabulous project she is working on at https://readingoldcemetery.uk. She said: It will be wonderful to find out more about Horatio Lewis Orton as we will be solving the mystery of a very beautiful grave monument at Reading Old Cemetery. We know that Mr Orton died in 1851 and his vault was bought by his son (Horace Rowe Orton) in 1853. Obviously, our route was to check with the experts, Martin Stower and Jean Coburn and much of the following research is indebted to them.[1] |

The one thing we know about our Victorian ancestors is that fortunes could be made by those willing to offer commitment, hard work and often risking their lives in dangerous conditions. These men tended to be unsophisticated, reckless, and often with uncompromising opinions. Sometimes the risks paid off but we start with Horatio Lewis’ business venture in Box which ended in bankruptcy.

Work in Box

Horatio Lewis Orton was one of the early excavators of the Box Tunnel, contracted by Isambard Kingdom Brunel to sink exploratory shafts on Box Hill, investigating the nature of the underground stone beds. The Orton family had previously worked with Brunel when Isambard and his father Marc were excavating the Thames Tunnel and in which Horatio’s brother Henry lost his life in 1828.[2]

Horatio and his partner Errington Paxton were awarded a contract to excavate 6 permanent and 2 temporary shafts in 1836 worth about £20,000.[3] The extent of water ingress severely compromised the work and the partnership was declared bankrupt on 27 June 1837.[4] The bankruptcy lumbered on slowly and was confirmed and a distribution made to creditors in 1841.[5] There were still complications and the accounts were submitted for audit in 1843 with final dividends being declared in 1850.[6]

There were several Orton family connections with Box. In 1841 Gustavus B Orton (1826-) was mentioned as living in Box village as a 15-year-old with an engineer Gustavus Augustus Beckers, Brunel’s assistant on excavating the Box Tunnel. It subsequently turned out that Horatio’s niece, Julia Augustus French Orton (1821-) was Gustavus Beckers step-daughter and she married Humphries Brewer, another of the Tunnel contract excavators at Gloucester in 1847. Clearly, a tightly-knit group of people.

Work in Box

Horatio Lewis Orton was one of the early excavators of the Box Tunnel, contracted by Isambard Kingdom Brunel to sink exploratory shafts on Box Hill, investigating the nature of the underground stone beds. The Orton family had previously worked with Brunel when Isambard and his father Marc were excavating the Thames Tunnel and in which Horatio’s brother Henry lost his life in 1828.[2]

Horatio and his partner Errington Paxton were awarded a contract to excavate 6 permanent and 2 temporary shafts in 1836 worth about £20,000.[3] The extent of water ingress severely compromised the work and the partnership was declared bankrupt on 27 June 1837.[4] The bankruptcy lumbered on slowly and was confirmed and a distribution made to creditors in 1841.[5] There were still complications and the accounts were submitted for audit in 1843 with final dividends being declared in 1850.[6]

There were several Orton family connections with Box. In 1841 Gustavus B Orton (1826-) was mentioned as living in Box village as a 15-year-old with an engineer Gustavus Augustus Beckers, Brunel’s assistant on excavating the Box Tunnel. It subsequently turned out that Horatio’s niece, Julia Augustus French Orton (1821-) was Gustavus Beckers step-daughter and she married Humphries Brewer, another of the Tunnel contract excavators at Gloucester in 1847. Clearly, a tightly-knit group of people.

Early Life

Horatio Lewis (21 March 1801-1851) was born at Walworth, South London, the son of James and Ann Orton. He was baptised a few weeks later at St Mary Woolnoth Church in the City of London. Horatio’s early life in London was as turbulent as his work in Box. This was a time when politics were febrile with the Peterloo Massacre of innocent civilians in 1819, the Cato Street Conspiracy of 1820, which attempted to murder the whole cabinet, and the unseemly public response to the coronation of George IV, when many people supported the estranged queen Caroline of Brunswick. It was a time that historians have claimed to be close to revolution.[7] In 1821 Horatio threw his lot in with the King and was appointed secretary of the Bridge Street Society, a group bringing legal cases against publishers who scandalised the monarchy with satirical cartoons.

In a letter to the Times in 1821 Horatio was directly connected with national political litigation.[8] Edward King, a bookseller in Chancery Lane claimed that Horatio had tried to defraud him by not paying for a copy of The Political Dictionary, a pamphlet which denounced the monarch and the government. The basis of the claims was that Horatio worked as a clerk for the Constitutional Society and was a monarchist, trying to suppress the publication. The bookseller gave a description of Horatio to warn others: About 5 foot 6 inches high; 20 years of age; moon-faced, dark eye brows; pallid sickly-looking complexion, with a general appearance of great constitutional debility; effeminate manners; a mincing mode of speaking; dandy-coloured clothes, and affected negligence of gait. Clearly this was a political attack rather than an independent observation and not totally reliable. Perhaps more reliable was Horatio’s description of his job as a newspaper copyist for his brother – in other words writing to the media with gossip and exclusive news. Horatio disputed the bookseller’s claims and counter-sued.[9] The whole attack on the monarchy was referred to the King’s Bench in October 1822.[10] Horatio confirmed that he was employed by the Constitutional Society at a salary of £80 a year. The judges held that the book was an attempt to overthrow the monarchy and the constitution along with other publications. Public opinion varied, however, and some newspapers described Horatio as a lying boy, employed by the Society to entrap the bookseller.[11]

Matters got worse for Horatio who was involved in a common assault on ex-Sheriff Joseph Wilfred Parkins in London on 18 May 1822. Mr Parkins had a premises in Bridge Street and was a close neighbour of the Constitutional Association’s offices. Horatio sought a showdown by accusing Mr Parkins of going into his room and taking his private papers. Horatio then launched an attack on Parkins with a stick and two fierce dogs joined in the affray. Horatio accused Mr Parkins of publishing his papers, implying that he may have been a printer. Horatio was found guilty and imprisoned for 2 months in Giltspur Street Prison.[12]

His problems continued when he was forced to deny that he had an acquaintance with a grave-robber in 1824 before he started work with Marc and Isambard Brunel on the Thames Tunnel excavation project at Rotherhithe. Again, it was a rocky ride, accused of theft of bricks lining the tunnel in 1827 and dismissed for insolence later that year. But he retained the support of Isambard Brunel who regarded him as his foreman and appointed him at Box and initial work at the Clifton Suspension Bridge in 1836.

Horatio Lewis (21 March 1801-1851) was born at Walworth, South London, the son of James and Ann Orton. He was baptised a few weeks later at St Mary Woolnoth Church in the City of London. Horatio’s early life in London was as turbulent as his work in Box. This was a time when politics were febrile with the Peterloo Massacre of innocent civilians in 1819, the Cato Street Conspiracy of 1820, which attempted to murder the whole cabinet, and the unseemly public response to the coronation of George IV, when many people supported the estranged queen Caroline of Brunswick. It was a time that historians have claimed to be close to revolution.[7] In 1821 Horatio threw his lot in with the King and was appointed secretary of the Bridge Street Society, a group bringing legal cases against publishers who scandalised the monarchy with satirical cartoons.

In a letter to the Times in 1821 Horatio was directly connected with national political litigation.[8] Edward King, a bookseller in Chancery Lane claimed that Horatio had tried to defraud him by not paying for a copy of The Political Dictionary, a pamphlet which denounced the monarch and the government. The basis of the claims was that Horatio worked as a clerk for the Constitutional Society and was a monarchist, trying to suppress the publication. The bookseller gave a description of Horatio to warn others: About 5 foot 6 inches high; 20 years of age; moon-faced, dark eye brows; pallid sickly-looking complexion, with a general appearance of great constitutional debility; effeminate manners; a mincing mode of speaking; dandy-coloured clothes, and affected negligence of gait. Clearly this was a political attack rather than an independent observation and not totally reliable. Perhaps more reliable was Horatio’s description of his job as a newspaper copyist for his brother – in other words writing to the media with gossip and exclusive news. Horatio disputed the bookseller’s claims and counter-sued.[9] The whole attack on the monarchy was referred to the King’s Bench in October 1822.[10] Horatio confirmed that he was employed by the Constitutional Society at a salary of £80 a year. The judges held that the book was an attempt to overthrow the monarchy and the constitution along with other publications. Public opinion varied, however, and some newspapers described Horatio as a lying boy, employed by the Society to entrap the bookseller.[11]

Matters got worse for Horatio who was involved in a common assault on ex-Sheriff Joseph Wilfred Parkins in London on 18 May 1822. Mr Parkins had a premises in Bridge Street and was a close neighbour of the Constitutional Association’s offices. Horatio sought a showdown by accusing Mr Parkins of going into his room and taking his private papers. Horatio then launched an attack on Parkins with a stick and two fierce dogs joined in the affray. Horatio accused Mr Parkins of publishing his papers, implying that he may have been a printer. Horatio was found guilty and imprisoned for 2 months in Giltspur Street Prison.[12]

His problems continued when he was forced to deny that he had an acquaintance with a grave-robber in 1824 before he started work with Marc and Isambard Brunel on the Thames Tunnel excavation project at Rotherhithe. Again, it was a rocky ride, accused of theft of bricks lining the tunnel in 1827 and dismissed for insolence later that year. But he retained the support of Isambard Brunel who regarded him as his foreman and appointed him at Box and initial work at the Clifton Suspension Bridge in 1836.

Freemasonry emblems sculpted on the Orton monument

Private Life

Despite working away so much, Horatio established a family after his marriage to Maria Curson at Deptford, Kent, in 1826. They sometimes moved around to be close to Horatio’s work but by 1844 Maria and he had moved to 101 Castle Street, Reading, where Horatio was described as a contractor in the 1851 census. He was still involved in the railways at times calling his place of employment as 101 Castle Street and Great Western Railway Station.[13] He rose in social status and joined the Freemasons, the Reading Lodge of Union in November 1843 and was given the freedom of the City of London by the Butchers’ Company in 1845.

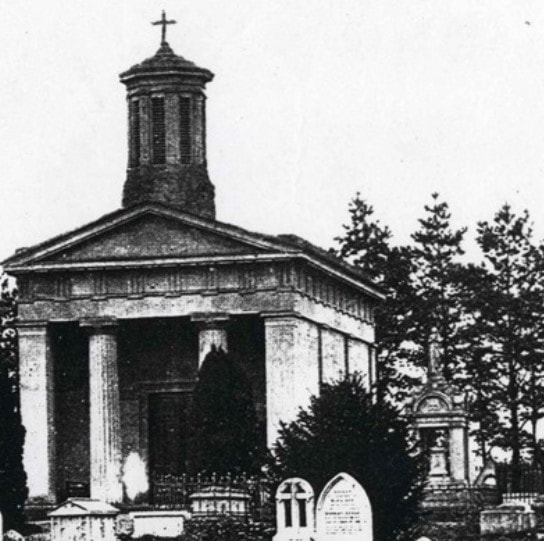

The Episcopal Chapel (next to Horatio's grave) has now been demolished but the building related to the Freemasons. The foundation stone was laid by the Brotherhood with a grand masonic procession from the town centre to the cemetery in October 1842.[14] It was well publicised in the newspapers at the time and rather fitting that he was buried at that spot and a tribute to Horatio ‘s status.

Despite working away so much, Horatio established a family after his marriage to Maria Curson at Deptford, Kent, in 1826. They sometimes moved around to be close to Horatio’s work but by 1844 Maria and he had moved to 101 Castle Street, Reading, where Horatio was described as a contractor in the 1851 census. He was still involved in the railways at times calling his place of employment as 101 Castle Street and Great Western Railway Station.[13] He rose in social status and joined the Freemasons, the Reading Lodge of Union in November 1843 and was given the freedom of the City of London by the Butchers’ Company in 1845.

The Episcopal Chapel (next to Horatio's grave) has now been demolished but the building related to the Freemasons. The foundation stone was laid by the Brotherhood with a grand masonic procession from the town centre to the cemetery in October 1842.[14] It was well publicised in the newspapers at the time and rather fitting that he was buried at that spot and a tribute to Horatio ‘s status.

A few months before he died in August 1851, Horatio had a brick grave built next to his own epitaph plot and six women were buried there: Mary Fry (1786-1847), Martha Blake (1796-1854), Sarah Frankum (1800-1857), Emma Frances George (1854-1860), Frances Frankum (1810-1871) and Sarah Gardiner (1823-1882). Most of these appear to be local needy people: Mary Fry lived at Castle Street; Sarah Frankum was an inmate at the St Lawrence Workhouse, Reading and she and her sister Frances had run a confectioners in Castle Street; Emma George a child in Castle Street; and Sarah Gardiner was the widow of a Reading railway labourer.

We can speculate that Horatio provided for these people as part of his new-found commitment to charity with the wealth he had managed to make by his own labours. As regards his own estate, Horatio left all his assets, tools and equipment to his eldest son Horace Rowe Orton in his will, subject to an annual payment of £30 to each of his other children, Ellen Maria and Harry Percy, during their minority plus some additional interest to Ellen Maria. He wanted certain of his domestic furnishings of china, glass and furniture to be sold and that Horace should pay his wife Maria £52 a year. His will was very much of a middle-class, affluent man at peace with his situation in life, contrary to his younger self. After his death Maria was recorded as a boarder in Kensington in 1861.

All that remains to complete this fascinating story is a picture of Horatio Orton. It would be marvellous to complete the research by Yota, Martin and Jean if readers could provide one of him or his family.

We can speculate that Horatio provided for these people as part of his new-found commitment to charity with the wealth he had managed to make by his own labours. As regards his own estate, Horatio left all his assets, tools and equipment to his eldest son Horace Rowe Orton in his will, subject to an annual payment of £30 to each of his other children, Ellen Maria and Harry Percy, during their minority plus some additional interest to Ellen Maria. He wanted certain of his domestic furnishings of china, glass and furniture to be sold and that Horace should pay his wife Maria £52 a year. His will was very much of a middle-class, affluent man at peace with his situation in life, contrary to his younger self. After his death Maria was recorded as a boarder in Kensington in 1861.

All that remains to complete this fascinating story is a picture of Horatio Orton. It would be marvellous to complete the research by Yota, Martin and Jean if readers could provide one of him or his family.

Family Tree

Parents: James and Ann Orton. Children included:

Horatio Lewis Orton (1801-22 August 1851) married Maria Curson in 1826. Children:

Parents: James and Ann Orton. Children included:

- Henry Feltham Orton (1790-1828) married Rebecca Denton in 1818;

- James (1793-);

- Horatio Lewis Orton (1801-22 August 1851);

- Joseph Gilson (1802-1873)

Horatio Lewis Orton (1801-22 August 1851) married Maria Curson in 1826. Children:

- Horace Rowe (1827 born in Chelsea-1910 died in West Ham);

- Ellen Maria (1834-1904) who married Henry John Brown in 1856. Children include Alice Brown (1861-1935) who married Spencer Calmeyer Charrington (1854-1930) in 1884;

- Clara Julia (1838-1843);

- Henry (1841-46);

- Harry (sometimes called Albert and at other times Percy Leicester) (1842-1924) who married Rosa and moved to Victoria, British Columbia.[15]

References

[1] www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/humphries-brewer.html

[2] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.15

[3] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.278

[4] London Gazette, 5 February 1838 declared the bankruptcy proceedings started on 20 June 1837

[5] London Gazette, 17 August 1841

[6] London Gazette, 17 March 1843, 5 November 1844 and 22 January 1850

[7] See Revolutionary Times - Box People and Places

[8] Repeated in Evening Mail, 6 June 1821 and various other papers including The Globe, 8 June 1821

[9] Oxford University and City Herald, 9 June 1821

[10] Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 22 October 1822

[11] The Birmingham Chronicle, 21 June 1821 and The Scotsman, 23 June 1821

[12] Commercial Chronicle (London), 2 July 1822

[13] Slater’s Directory for Berkshire, 1852

[14] The Reading Mercury, 15 October 1842

[15] Victoria Daily Colonist, British Columbia, 23 August 1923, p. 5

[1] www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/humphries-brewer.html

[2] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.15

[3] David Pollard, Digging Bath Stone, 2021, Lightmoor Press, p.278

[4] London Gazette, 5 February 1838 declared the bankruptcy proceedings started on 20 June 1837

[5] London Gazette, 17 August 1841

[6] London Gazette, 17 March 1843, 5 November 1844 and 22 January 1850

[7] See Revolutionary Times - Box People and Places

[8] Repeated in Evening Mail, 6 June 1821 and various other papers including The Globe, 8 June 1821

[9] Oxford University and City Herald, 9 June 1821

[10] Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 22 October 1822

[11] The Birmingham Chronicle, 21 June 1821 and The Scotsman, 23 June 1821

[12] Commercial Chronicle (London), 2 July 1822

[13] Slater’s Directory for Berkshire, 1852

[14] The Reading Mercury, 15 October 1842

[15] Victoria Daily Colonist, British Columbia, 23 August 1923, p. 5