|

Discovering the

Grove Inn, Ashley, and Death of Ann Little, 1841 Murder or Manslaughter? Researched and extracted from newspaper records by Peter Ford (after initial details were published in Box Parish Magazine) and residents of Ashley. March 2015 |

This intriguing story discovers a new pub in Box, The Grove Inn at Ashley. It also reveals the brutal death of Ann Little by her partner Isaac Smith. We follow events through the report of the inquest proceedings in 1841, then descriptions of the participants and finally the trial and the verdict in 1842. Be prepared for some graphic descriptions of the deadly deed, as well as new discoveries about Box.

An inquest was held at Ashley, near Box, before WB Whitmarsh, Esq, Coroner, on the body of Ann Little, a poor woman who had been murdered with great barbarity early on Sunday morning.[1] The deceased, who it appeared from the evidence, was a single woman, about 40 years of age, lived with a married man named as Isaac Smith, as his wife, by whom she had several children, one of whom was an infant at the breast at the time of the murder.

From the outset, we can confirm these people were real because the 1841 census records Isaac Smith, quarryman aged 30, living with Ann Little, aged 40, at Kingsdown with the children George Little (agricultural labourer aged 15 years), Thomas Little (14), James Little (7), Isaac Little (9 months), William Smith (quarryman 14 years) and Francis Smith (agricultural labourer aged 11).

The Inquest

Witnesses' Evidence

The following witnesses were examined:

Benjamin Fluster, landlord of The Grove Inn, Box - deposed to the fact of the parties drinking at his house on Saturday evening, that the prisoner and the deceased were three parts drunk when they left the house: and that Smith’s two sons were with them.

The following witnesses were examined:

Benjamin Fluster, landlord of The Grove Inn, Box - deposed to the fact of the parties drinking at his house on Saturday evening, that the prisoner and the deceased were three parts drunk when they left the house: and that Smith’s two sons were with them.

At this point the information is problematic. There is no record of the name Fluster, nor of a pub called the Grove in Ashley.

Nicola Sly's book "Wiltshire Murders" [2] places the pub in Ashley, near Box but there is no record of a licensed house there.

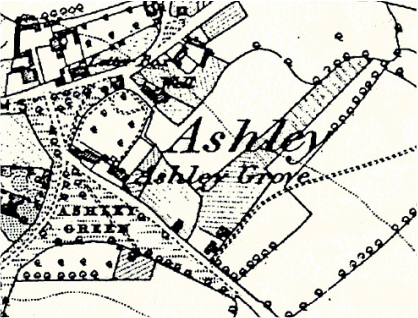

The best information we have is that "Ashley Grove" is marked as a location in Ashley in the 1885 Ordnance Survey map shown at the heading of this article.

We should not be surprised that the pub's name doesn't appear on the official magistrate's license list. The 1830 Beer-house Act had allowed anyone to sell beer provided that they paid a fee of two guineas as a way of encouraging people to drink less gin at the registered pubs. As a result, thousands of new beer-houses arose throughout England.

Nicola Sly's book "Wiltshire Murders" [2] places the pub in Ashley, near Box but there is no record of a licensed house there.

The best information we have is that "Ashley Grove" is marked as a location in Ashley in the 1885 Ordnance Survey map shown at the heading of this article.

We should not be surprised that the pub's name doesn't appear on the official magistrate's license list. The 1830 Beer-house Act had allowed anyone to sell beer provided that they paid a fee of two guineas as a way of encouraging people to drink less gin at the registered pubs. As a result, thousands of new beer-houses arose throughout England.

William Smith – I am fifteen years old and a son of Isaac Smith, the prisoner. On Saturday evening last, I and my father left off work at five o’clock, and went to be paid at Box; we stayed there a main bit, and then we went to The Grove Inn. The deceased, Ann Little, came into the tap-room at about a quarter past nine o’clock, with my brother Francis. She had a babe in her arms, and was tipsy. My father drank with her and I also. He paid for five pints of beer.

We left at ten o’clock. My father was tipsy, but not so much as Ann Little. They were friendly together whilst in the tap room. On the way home my father asked her for a shilling so he might go to The Swan Inn and have a pint more of beer; and upon her refusing him, my father replied that he wouldn’t go any farther until he had it, and there Ann gave him a shilling.

They went on afterwards very comfortably until we came to the New House, at (Isaac) Gibbon’s, which is between fifty and sixty yards from the cottage we live in. Father then asked how much money she had drawed at Master’s? She replied I shall not tell you. He then asked how much beer she had that afternoon? She replied one pint.[3] He then knocked her down upon the grass, with his fist, and Francis, my brother, had the babe in his arms; she got up and sat down on a heap of stones, whilst I and father went to our cottage. The door was locked – father tried to burst it open and not being able to do it, he went after the key.

We left at ten o’clock. My father was tipsy, but not so much as Ann Little. They were friendly together whilst in the tap room. On the way home my father asked her for a shilling so he might go to The Swan Inn and have a pint more of beer; and upon her refusing him, my father replied that he wouldn’t go any farther until he had it, and there Ann gave him a shilling.

They went on afterwards very comfortably until we came to the New House, at (Isaac) Gibbon’s, which is between fifty and sixty yards from the cottage we live in. Father then asked how much money she had drawed at Master’s? She replied I shall not tell you. He then asked how much beer she had that afternoon? She replied one pint.[3] He then knocked her down upon the grass, with his fist, and Francis, my brother, had the babe in his arms; she got up and sat down on a heap of stones, whilst I and father went to our cottage. The door was locked – father tried to burst it open and not being able to do it, he went after the key.

|

We met Ann coming from the Swan. Father asked her why she had run away? And receiving no answer, he knocked her down with his fist. Whilst lying on the grass, he asked her if she was going to get up? – and upon her saying, that she would not, he hit her with his fist several times.

|

Knocked her Down |

In two or three minutes, she got up, and began to walk home with him, but she had not walked more than six or seven yards, when she sat down on the grass. Father asked what she sat down for? And receiving no answer, he hit her again with his fist, and kicked her behind with his boot, which was tip’t and nailed.

She then got up, walked on a few yards to James Gale’s cottage, and sat down on the grass.[4] Father asked her to get up, and having no answer, he hit her with his fist and kicked her again. He tried to lift her up by the arms, and drop’t her down, and then walked on a few yards, and returned, when he took her up on his back and carried her to between midway of the Swan and her cottage, saying that his back ached and he put her down on the grass, when she did not speak, but sat up.

In five minutes afterwards he carried her on his back into the cottage, and placed her on the floor. At this moment the babe cried, and Father asked her to give it the breast; and she said, Bring me the child! and then suckled it for six or seven minutes, and my brother Francis took the child again. She laid down on the floor, and father went to sleep in a chair by the fireside. Soon afterwards, Ann asked me to help her up into a chair, which I did; father awoke and then we went up to bed about four o’clock, leaving her asleep in the chair, and alone down stairs!

She then got up, walked on a few yards to James Gale’s cottage, and sat down on the grass.[4] Father asked her to get up, and having no answer, he hit her with his fist and kicked her again. He tried to lift her up by the arms, and drop’t her down, and then walked on a few yards, and returned, when he took her up on his back and carried her to between midway of the Swan and her cottage, saying that his back ached and he put her down on the grass, when she did not speak, but sat up.

In five minutes afterwards he carried her on his back into the cottage, and placed her on the floor. At this moment the babe cried, and Father asked her to give it the breast; and she said, Bring me the child! and then suckled it for six or seven minutes, and my brother Francis took the child again. She laid down on the floor, and father went to sleep in a chair by the fireside. Soon afterwards, Ann asked me to help her up into a chair, which I did; father awoke and then we went up to bed about four o’clock, leaving her asleep in the chair, and alone down stairs!

|

Just as the sun was getting up, Thomas Little, her son, came up, saying Isaac, my Mother is dead ! Father said Is she? and immediately went down, and returned in five minutes, and then got into bed, having asked me to get up and call someone.

|

My Mother |

When she was brought indoor by Isaac Smith, she had a black eye and some blood was upon it. Blood was also dropping off from the tail of her gown on the floor.

Harriet (Charlotte) Tye, [5] of Box - I was at home about a quarter before 12 o’clock, in the parish of Box, on Saturday night last. Our dog barked, when I opened the door, and went out into the Common, where I saw Ann Little lying on the ground, and Isaac Smith cursing, beating and kicking her. Ann Little said, For the Lord’s sake, don’t hit me anymore, for I have got one black eye and you will give me another! He then hit her in the face with his fist twice; and afterwards went across the road.

She got up to follow him, when he turned round and knocked her down, saying D—your eyes, get up, or else I will kill you directly! She said Isaac, help me up! I am not able to bear it. He replied Don’t be so false, or I will throw you into the hedge. I was afraid to stay out any longer, and went in-door and told my father who was gone to bed who the parties were a quarrelling.

She got up to follow him, when he turned round and knocked her down, saying D—your eyes, get up, or else I will kill you directly! She said Isaac, help me up! I am not able to bear it. He replied Don’t be so false, or I will throw you into the hedge. I was afraid to stay out any longer, and went in-door and told my father who was gone to bed who the parties were a quarrelling.

James Gale, of Box - About 12 o’clock on Saturday night last, as I was in bed, at Kingsdown, in the parish of Box, I heard Ann Little cry out Oh, my dear Isaac! I then went to the window and saw her lying on the side of the road, and Isaac Smith standing by her side and cursing her. He took her under the arms, and dragged her feet on the ground, across the road, and let her fall. He then began to curse and to hit her with both his fists, and to kick her, which he did several times.

After this he asked her to get up, but she made no answer. He then endeavoured to lift her up but he laid her down again, when he kicked and struck her again. He then dragged her out of my sight, and I went back to bed.

Thomas Bath, constable, of Box - deposed that when he took Smith into custody, he (Smith) said that he had beaten her scores of times; he did not think it would come to this. He supposed he was done, and should not come there no more. He wished the children goodbye and told them to mind their uncle.

After this he asked her to get up, but she made no answer. He then endeavoured to lift her up but he laid her down again, when he kicked and struck her again. He then dragged her out of my sight, and I went back to bed.

Thomas Bath, constable, of Box - deposed that when he took Smith into custody, he (Smith) said that he had beaten her scores of times; he did not think it would come to this. He supposed he was done, and should not come there no more. He wished the children goodbye and told them to mind their uncle.

Mr Goldstone [6], surgeon of Box, was examined, and from his evidence, it appeared, that besides the brutality above deposed to, the prisoner must have punctured the unfortunate woman with some instrument, and that the haemorrhage resulting from three lacerations, was the cause of death.

The Inquest Jury returned its verdict that Isaac Smith should be committed to the New Prison, Devizes for trial for Murder.

The People

|

The following is a brief history of the deceased and the accused.

The accused is a widower, named Isaac Smith, known as Crafty Ike, a mason. |

Smith Known Locally as |

The murdered woman is Ann Little, with whom he co-habited, an unmarried woman, of most abandoned character, the mother of five illegitimate children by different men. She was in her younger days in good circumstances, but being of a depraved turn of mind, went to London, and was on the town (a prostitute).

She returned to Box and has latterly resided at a cottage of her own at the point of Kingsdown, near the three firs, so prominent a landmark from the London Road. The house has for some years been the receptacle for thieves and persons of bad character and too often of the produce of the night’s plunder – sheep and lambs having often been lost by the neighbouring farmers and traced to this locality. Ann Little was not very long since convicted at the Warminster Sessions of stealing potatoes and found guilty, for which she was sentenced to three months imprisonment.

Smith has himself five children, but although given to habits of drunkenness, is a hard working man, and bore a good character before the death of his late (first) wife, although it was reported he starved her to death. The children, as it may be supposed, are as ignorant as any heathens, never frequenting Church or any other place of worship – the youngest boy aged 14, and not knowing the nature of an oath, so that the Coroner and Jury objected to take his evidence.

A lamentable instance of the ignorance still to be found in this Christian land was exhibited in the course of the day. A son of the deceased, named Thomas Little, was brought forward for examination: but his evidence was not admissible in consequence of his being unacquainted with an oath. In answer to questions put to him by the coroner, it appeared he had never gone to Church or Chapel, did not know his catechism: did not know the consequence of telling a lie: and had never heard of a Bible or a God! The lad was about 12 years of age.

Smith and the woman Ann Little, went to Box Church to be married, the Banns were published but they either had not the money to pay the fees or drank it away on the road to Church – it is not known which – but they returned home without the ceremony being performed, and continued to live together until the above fatal act put a period to their illicit intercourse. A brother of the accused has been transported and the eldest son of Little is now in gaol.

She returned to Box and has latterly resided at a cottage of her own at the point of Kingsdown, near the three firs, so prominent a landmark from the London Road. The house has for some years been the receptacle for thieves and persons of bad character and too often of the produce of the night’s plunder – sheep and lambs having often been lost by the neighbouring farmers and traced to this locality. Ann Little was not very long since convicted at the Warminster Sessions of stealing potatoes and found guilty, for which she was sentenced to three months imprisonment.

Smith has himself five children, but although given to habits of drunkenness, is a hard working man, and bore a good character before the death of his late (first) wife, although it was reported he starved her to death. The children, as it may be supposed, are as ignorant as any heathens, never frequenting Church or any other place of worship – the youngest boy aged 14, and not knowing the nature of an oath, so that the Coroner and Jury objected to take his evidence.

A lamentable instance of the ignorance still to be found in this Christian land was exhibited in the course of the day. A son of the deceased, named Thomas Little, was brought forward for examination: but his evidence was not admissible in consequence of his being unacquainted with an oath. In answer to questions put to him by the coroner, it appeared he had never gone to Church or Chapel, did not know his catechism: did not know the consequence of telling a lie: and had never heard of a Bible or a God! The lad was about 12 years of age.

Smith and the woman Ann Little, went to Box Church to be married, the Banns were published but they either had not the money to pay the fees or drank it away on the road to Church – it is not known which – but they returned home without the ceremony being performed, and continued to live together until the above fatal act put a period to their illicit intercourse. A brother of the accused has been transported and the eldest son of Little is now in gaol.

The Trial

Having established that there was a case to be answered, Isaac was tried for the wilful murder of Ann Little. The following is the additional evidence given. Mr Merewether conducted the case for the prosecution and Mr Edwards defended the prisoner. The following evidence was given before the judge Mr Justice Coleridge.[7]

Benjamin Fluster – I am the landlord of the Grove Inn, at Box: the prisoner came to my house about seven of the evening of the 4th of September: about half past seven Ann Little came in, and they drank together 4 pints of beer. The prisoner’s son William was there also. They all left at ten o’ clock. They were about three parts tipsy. They were quiet and peaceable. Cross – examined – The deceased could stand very well. The prisoner’s son William Smith is 15 years of age.

William Smith – I am the son of the prisoner, and live at Box with my father. Ann Little lived with my father. On Saturday 4th of September, I was at work with my father: when we left off work we received our wages, and then went to the Grove public house... My father asked what money she had drawn? But she would not tell. He asked what beer she had had.

William Smith – I am the son of the prisoner, and live at Box with my father. Ann Little lived with my father. On Saturday 4th of September, I was at work with my father: when we left off work we received our wages, and then went to the Grove public house... My father asked what money she had drawn? But she would not tell. He asked what beer she had had.

Clues about Grove Inn, Ashley |

She said she had three pints, my father asked her where? She said one at Mr Hobbs, at Box, and the other at Benjamin Fluthers (sic) . He asked who drew it? She said Sophia first, and then Benjamin [8]; after this they quarrelled mainly, and pitched into one another... When we got to the cottage, we found the door was locked.

|

My brother came and said she was gone to the Swan, with the key in her pocket – we then went towards the Swan and met her coming along. Father asked where she had been? She said to the Swan; he then hit her down with his fist... When we got home, he (father) took a knife out of her pocket, which knife I had next morning, my father gave it to me that night, directly he took it out of her pocket. Father had a knife of his own, next morning father’s knife was on a chair, by the bedside.

The name of the landlord appears in different spellings in the official record and this was a great clue to finding the pub in Ashley. The surname has various spellings: Fluster, Fluthers, Fluester and Huester. It was possibly pronounced with regional dialect which caused the spelling variations. The 1841 census shows Benjamin Huester, aged 25 and recorded as a mason, living with wife Elizabeth, aged 20, and three others: Rhoda Picton (aged 60 years), Sophia Picton (17 years) and Bethia (8 years). So we have the names of the people who served the drinks to Ann: Benjamin and Sophia.

We can go further and track the whereabouts of the house in the 1841 census which lists the properties in sequence. The list of residences runs Ashley House, the pub, a cottage, then Ashley Cottage. We can conclude that the pub is situated in the same general location as these other properties.

We can go further and track the whereabouts of the house in the 1841 census which lists the properties in sequence. The list of residences runs Ashley House, the pub, a cottage, then Ashley Cottage. We can conclude that the pub is situated in the same general location as these other properties.

Frank Smith – I am 12 years of age, the prisoner is my father. On the 4th of September I went with Ann Little to Fluster’s, when we came away I carried the baby, I got into the cottage through the window. I went back to where father was. I saw father and Ann Little fighting; when father brought mother home he threw her down on the floor and said she might bide there and die.

|

Breakthrough

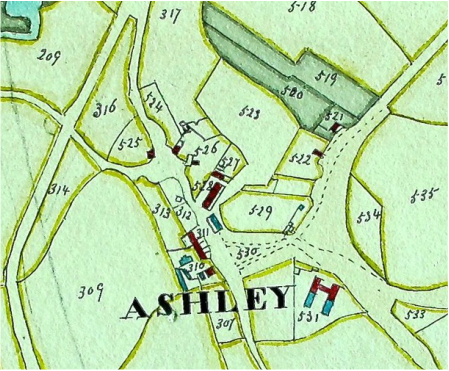

The 1840 Tithe Apportionment record lists the name Benjamin Fluester (with Thomas Noble) as the occupier of a beerhouse and court and dwellinghouse and shop at entry number 529b, a property on the large plot 529. More than this, the map which accompanies the record of tenants shows precisely where other properties were located. On the left side of Ashley Lane are: 310 Ashley Farmhouse and outbuildings occupied by Joseph Pocock, yeoman, and owned by the Northey family, lords of the manor of Box. 311 Single house and garden 312 House and Garden 313 Paddock to Ashley Farm |

On the right-hand side of Ashley Lane are the properties that we are mostly concerned with:

529 facing Doctor's Hill is Ashley Grove, a large dwelling-house with paddock, offices, coach house, stables and gardener's cottage occupied by James Barnett, Esq.

529a and 529b are not identified but they are marked in blue as a wayside cottage on Ashley Lane, probably a shack built without planning permission and occupied by various families.

529a was occupied by Charles Ashby.

529b is the location of The Grove beer-house and courtyard and a dwelling-house and shop, in the joint occupation of Benjamin Fluester and Thomas Noble.

530 is Ashley Green Common owned by the Northeys.

528 marks George Newman's house which he shared with Anthony Smith and the families of Isaac Smith and Ann Little.

George Newman's reference to The Swan is puzzling; it may be an error and Newman meant to say The Grove.

The earlier references by the Smith family to The Swan are presumably correct.

526 is presumed to be Ashley Cottage, where the surgeon Joseph Goldstone lived.

531 is Ashley Manor House owned by Henry Sudell.

532 (to the left of 533) is Ashley Leigh.

The trial continued with further evidence.

529 facing Doctor's Hill is Ashley Grove, a large dwelling-house with paddock, offices, coach house, stables and gardener's cottage occupied by James Barnett, Esq.

529a and 529b are not identified but they are marked in blue as a wayside cottage on Ashley Lane, probably a shack built without planning permission and occupied by various families.

529a was occupied by Charles Ashby.

529b is the location of The Grove beer-house and courtyard and a dwelling-house and shop, in the joint occupation of Benjamin Fluester and Thomas Noble.

530 is Ashley Green Common owned by the Northeys.

528 marks George Newman's house which he shared with Anthony Smith and the families of Isaac Smith and Ann Little.

George Newman's reference to The Swan is puzzling; it may be an error and Newman meant to say The Grove.

The earlier references by the Smith family to The Swan are presumably correct.

526 is presumed to be Ashley Cottage, where the surgeon Joseph Goldstone lived.

531 is Ashley Manor House owned by Henry Sudell.

532 (to the left of 533) is Ashley Leigh.

The trial continued with further evidence.

George Newman [9] – I am a Quarryman at Box. I heard a noise that night between the Swan and Smith’s where I live. The voices were those of the prisoner and the deceased. They were 35 yards from me. I saw the prisoner knock her down and kick her and I heard her say Lord Isaac, you have killed me. He said D—your eyes, I will kill you. I did not interfere because they often quarrelled and if any one endeavoured to separate them, they would both turn upon them, and thrash them. She was generally in the wrong.

Joseph Goldstone, surgeon – I reside at Box. I was called in to see the deceased. She was sitting on a chair by the fire, and had been dead for some few hours. Her face was bruised considerably – her clothes were wet and bloody, her stockings and under garments were drenched with blood , from her hips downwards. At the back of her undergarment, there was a cut or scar. I made a post mortem examination on the Monday, the body was covered with blood from the hips. The legs were greatly bruised. I found a laceration extending upwards of 4 inches and another two inches long, and there was a third of the same length. The wounds must have been done by some sharp instrument. I attribute the death to those wounds, causing a great effusion of blood. The wounds could not have been occasioned by the kick of a boot only. The wounds might have been occasioned by the knife, which belonged to the prisoner – but I still do not think it probable.

Joseph Goldstone, surgeon – I reside at Box. I was called in to see the deceased. She was sitting on a chair by the fire, and had been dead for some few hours. Her face was bruised considerably – her clothes were wet and bloody, her stockings and under garments were drenched with blood , from her hips downwards. At the back of her undergarment, there was a cut or scar. I made a post mortem examination on the Monday, the body was covered with blood from the hips. The legs were greatly bruised. I found a laceration extending upwards of 4 inches and another two inches long, and there was a third of the same length. The wounds must have been done by some sharp instrument. I attribute the death to those wounds, causing a great effusion of blood. The wounds could not have been occasioned by the kick of a boot only. The wounds might have been occasioned by the knife, which belonged to the prisoner – but I still do not think it probable.

The Verdict

Mr Justice Coleridge then summed up the case to the jury. Under this indictment they might either find the prisoner guilty of murder or manslaughter, or of a common assault. The difference between murder and manslaughter consisted in one being supposed to be done with malice aforethought, and the other in the supposed absence of malice.

Malice aforethought did not imply a previously conceived intention. If you took a pistol and put it to the head of a man and blew his brains out, though it might have been done in a passion, still as you knew what you were about and that it would take his life away, that would be murder. On the other hand, if certain provocations were given, and the blood became heated, and before it had time to cool, you did the same act, the Law would make allowance for human infirmity.

But the law did not allow drunkenness to be any palliative for crime. If such an act were done by a man when drunk, it would be equally murder, as if he were sober. No man had right to suppose he might get drunk, do acts and then get excused on the grounds of his being drunk.

The Jury, after some consideration, returned a verdict of Guilty of Murder. His Lordship observed to them, that he hoped they had not allowed the drunken expressions of the prisoner to have much weight with them. One of the Jury said – he understood the learned Judge to say they could not reduce the offence from murder to manslaughter. His Lordship said he did not mean to convey that idea, by any means. The Jury then said their verdict would be Manslaughter.

Malice aforethought did not imply a previously conceived intention. If you took a pistol and put it to the head of a man and blew his brains out, though it might have been done in a passion, still as you knew what you were about and that it would take his life away, that would be murder. On the other hand, if certain provocations were given, and the blood became heated, and before it had time to cool, you did the same act, the Law would make allowance for human infirmity.

But the law did not allow drunkenness to be any palliative for crime. If such an act were done by a man when drunk, it would be equally murder, as if he were sober. No man had right to suppose he might get drunk, do acts and then get excused on the grounds of his being drunk.

The Jury, after some consideration, returned a verdict of Guilty of Murder. His Lordship observed to them, that he hoped they had not allowed the drunken expressions of the prisoner to have much weight with them. One of the Jury said – he understood the learned Judge to say they could not reduce the offence from murder to manslaughter. His Lordship said he did not mean to convey that idea, by any means. The Jury then said their verdict would be Manslaughter.

Judgement

Mr Justice Coleridge told the prisoner he had had a very narrow escape, for had the Jury found him guilty of murder, he would have had no choice, but must have passed upon him the extreme penalty of the law. From that painful duty he was happy to say he was now relieved. The crime, however, which he had been convicted, was one little short of murder.

He was living a widower, with children grown up, to whom he ought to have set a better example, but before them he was living in commission of a deadly sin, with another woman. Still, she was not the person upon whom he had any right to exercise cruelty. They were both drunk that night, and were teaching their children, young as they were, a course of drinking, by which vice, he believed, more crimes were committed than by any other.

If he had any good feeling he would not think of himself, nor of his children, nor of his country, but to his dying day would think of that poor woman whom he had sent unprepared out of the world. He was then sentenced to Transportation for Life.

Outcome

Isaac Smith was transported to Australia on the Maitland from Plymouth, on the 26th August 1843, one of 199 convicts.[10]

The records shows he had been convicted at Wiltshire Assizes for a Term of Life.

Mr Justice Coleridge told the prisoner he had had a very narrow escape, for had the Jury found him guilty of murder, he would have had no choice, but must have passed upon him the extreme penalty of the law. From that painful duty he was happy to say he was now relieved. The crime, however, which he had been convicted, was one little short of murder.

He was living a widower, with children grown up, to whom he ought to have set a better example, but before them he was living in commission of a deadly sin, with another woman. Still, she was not the person upon whom he had any right to exercise cruelty. They were both drunk that night, and were teaching their children, young as they were, a course of drinking, by which vice, he believed, more crimes were committed than by any other.

If he had any good feeling he would not think of himself, nor of his children, nor of his country, but to his dying day would think of that poor woman whom he had sent unprepared out of the world. He was then sentenced to Transportation for Life.

Outcome

Isaac Smith was transported to Australia on the Maitland from Plymouth, on the 26th August 1843, one of 199 convicts.[10]

The records shows he had been convicted at Wiltshire Assizes for a Term of Life.

|

The Maitland arrived on the seventh of February 1884 in the Port of Norfolk Island. The voyage is listed as being 159 days, although it also says it departed on 1st September 1843. At present, it looks as though he could have disembarked at New South Wales or Norfolk Island. Norfolk Island was not one of the best places to serve a sentence, it is east of New Zealand and has a poor reputation.

Left: Convict ship Maitland (sourced from www.convictrecords.com.au/ships/maitland) |

On the Convicts To Australia website, the Maitland is featured twice between 1840 and 1847. On one voyage, it says it was sent to Norfolk Island (and Sydney and Hobart) during 1840 to 1847. Sailed 01-09-1843 Plymouth, Port Norfolk Island. 200 Embarked, Surgeon Allan McLaren.

This article was a real detective chase to find the drinking house The Grove Inn, Ashley. The evidence points to the site of what is now called Crofton on Ashley Lane. The story of this Box pub also shows much about our predecessors,contemporary attitudes towards women, religion and alcohol. It challenges our views of Victorian blame and guilt. It throws a perspective on violence (often in domestic sitations common against women and associated with excessive consumtion of alcohol) and it reveals judicial compassion in the face of a jury's ignorance, albeit preferred when defendants were God-fearing. It challenges us to think about the media reports of the time and the inflammatory use of language.

This article was a real detective chase to find the drinking house The Grove Inn, Ashley. The evidence points to the site of what is now called Crofton on Ashley Lane. The story of this Box pub also shows much about our predecessors,contemporary attitudes towards women, religion and alcohol. It challenges our views of Victorian blame and guilt. It throws a perspective on violence (often in domestic sitations common against women and associated with excessive consumtion of alcohol) and it reveals judicial compassion in the face of a jury's ignorance, albeit preferred when defendants were God-fearing. It challenges us to think about the media reports of the time and the inflammatory use of language.

References

[1] Devizes & Wiltshire Gazette Thursday, September 9th 1841

[2] Nicola Sly, Wiltshire Murders, 2009

[3] Under oath at the trial, William changed the one pint to three pints.

[4] James Gale is recorded in the 1841 census as aged 45 living with wife Mary and 5 children at Kingsdown.

[5] Aged 20 in 1841 also living in Kingsdown.

[6] Robert Goldstone of Marshfield is mentioned at the inquest but this appears to be an error. Joseph Goldstone, surgeon aged 30 years in 1841, is referred to at the trial. He lived at Ashley Cottage, Box.

[7] Devizes & Wiltshire Gazette, Thursday March 10th 1842

[8] Benjamin Huester and Sophia Picton

[9] Recorded as 50 years old living at Ashley in 1841. The Tithe record records him as living in part of Ashley Cottage.

[10] Australian Joint Copying Project – Microfilm 91 HO11/13 Page 405 (204)

[1] Devizes & Wiltshire Gazette Thursday, September 9th 1841

[2] Nicola Sly, Wiltshire Murders, 2009

[3] Under oath at the trial, William changed the one pint to three pints.

[4] James Gale is recorded in the 1841 census as aged 45 living with wife Mary and 5 children at Kingsdown.

[5] Aged 20 in 1841 also living in Kingsdown.

[6] Robert Goldstone of Marshfield is mentioned at the inquest but this appears to be an error. Joseph Goldstone, surgeon aged 30 years in 1841, is referred to at the trial. He lived at Ashley Cottage, Box.

[7] Devizes & Wiltshire Gazette, Thursday March 10th 1842

[8] Benjamin Huester and Sophia Picton

[9] Recorded as 50 years old living at Ashley in 1841. The Tithe record records him as living in part of Ashley Cottage.

[10] Australian Joint Copying Project – Microfilm 91 HO11/13 Page 405 (204)