Gingell Family in Box Paula Pardoe December 2020

My great grandfather, Joseph John Gingell, left Box and moved to Nottingham sometime in the 1880s. He worked on the railway and, for some reason, when he moved to Nottingham, he changed the spelling of his surname to Gingle, which was my maiden name. I started doing genealogy after I visited Box with my father a long time ago when we saw two Gingell names on the War Memorial and decided to find out if we were related, which indeed we were.

My Gingell Family at Box Hill

The first recorded instance I have of my Gingell family in Box was my great, great, great grandfather William Gingell (1811 – 1873). He came from Clack, near Lyneham, and married Elizabeth Head in Box in January 1839. Elizabeth had been born in Box in 1814, as was her father Joseph (1785-1852). Joseph was a quarrier (described in 1819 as tiledigger) living at Box Hill who took over a beer-house, probably the Quarryman’s Arms, before 1851. William Gingell followed the same quarry trade and was listed on the 1851 census as a quarryman at Box Quarries.

In 1861 they were still living at Box, the address described as Box on the Hill., possibly one of the quarrymen’s cottages built by Thomas Strong for his workers or those owned by Clift Quarry Works run by the Pictor family. By 1871 the address had changed back to Box Quarry again, possibly indicating that it was the same house. Elizabeth died in 1872 and sixty-two-year-old William was killed in 1873 when a ceiling gave way in the quarry.[1] Four men were extracting stone when the overhang of the face collapsed on them all. Three of the men escaped but William was reported as killed instantly when his body was recovered an hour later.

The first recorded instance I have of my Gingell family in Box was my great, great, great grandfather William Gingell (1811 – 1873). He came from Clack, near Lyneham, and married Elizabeth Head in Box in January 1839. Elizabeth had been born in Box in 1814, as was her father Joseph (1785-1852). Joseph was a quarrier (described in 1819 as tiledigger) living at Box Hill who took over a beer-house, probably the Quarryman’s Arms, before 1851. William Gingell followed the same quarry trade and was listed on the 1851 census as a quarryman at Box Quarries.

In 1861 they were still living at Box, the address described as Box on the Hill., possibly one of the quarrymen’s cottages built by Thomas Strong for his workers or those owned by Clift Quarry Works run by the Pictor family. By 1871 the address had changed back to Box Quarry again, possibly indicating that it was the same house. Elizabeth died in 1872 and sixty-two-year-old William was killed in 1873 when a ceiling gave way in the quarry.[1] Four men were extracting stone when the overhang of the face collapsed on them all. Three of the men escaped but William was reported as killed instantly when his body was recovered an hour later.

Two of William’s sons also worked in the quarry industry, including John Gingell (1839 – 1915), my two-times great grandfather. Twenty-two-year-old John was shown as a masons’ labourer in the 1861 census, in other words doing all the hard graft of lifting, fetching and carrying blocks of building stone and clearing the rubble. In June 1861 he married Rosina Allen. A branch of the Allens had lived in Box since the 1760s and in the earliest censuses this part of the family were recorded at Kingsdown, another stone quarrying area where head of the household John Allen (b 1811) worked as a mason’s labourer. We can see how tightly-knit the quarry families were when John’s younger brother Joseph (another quarryman) married Rosina’s sister, Mary Allen in December 1861. Joseph himself is an interesting person, working as a blacksmith tending the horses of Clift Quarry Works and living at Box Hill-on-the-Road with his family.

By 1871 John and Rosina had moved to Henley and in 1881 John was recorded as a quarryman living in Ashley. I couldn’t imagine what it was like for John still working in a quarry after his father had been tragically killed in 1873. Perhaps that was why he shifted to another site at Longsplatt Quarry, away from Box Hill. Rosina died in 1888 and, with three children under 10 to manage, John married again in 1890 to Susan Nicks (nee Owen), widow. Her first husband had been Abraham Nicks, a Bath tailor, but he died in 1882 and she supported her three children by working as a dressmaker. By 1891 John and Susan were living at Longsplatt where John was still described as a stone quarryman. His life appears to have been unremittingly hard, always an underground miner, never becoming a skilled stonemason shaping and engraving the stone on the surface. His second marriage was short-lived as Susan died a couple of years later in 1893. In 1901 John was still living at Longsplatt, this time boarding with his daughter Elizabeth and son-in-law Henry Coles, quarryman, in a property called No 4, Longsplatt. We might suppose that these were tenanted properties close to the site of Longsplatt Quarry (now called The Old Quarry). John was still there in 1911, described as an Old Age Pensioner, Quarriman (sic), at a time shortly after old age pensions had been introduced for over 70s in 1909. He died in 1911.

By 1871 John and Rosina had moved to Henley and in 1881 John was recorded as a quarryman living in Ashley. I couldn’t imagine what it was like for John still working in a quarry after his father had been tragically killed in 1873. Perhaps that was why he shifted to another site at Longsplatt Quarry, away from Box Hill. Rosina died in 1888 and, with three children under 10 to manage, John married again in 1890 to Susan Nicks (nee Owen), widow. Her first husband had been Abraham Nicks, a Bath tailor, but he died in 1882 and she supported her three children by working as a dressmaker. By 1891 John and Susan were living at Longsplatt where John was still described as a stone quarryman. His life appears to have been unremittingly hard, always an underground miner, never becoming a skilled stonemason shaping and engraving the stone on the surface. His second marriage was short-lived as Susan died a couple of years later in 1893. In 1901 John was still living at Longsplatt, this time boarding with his daughter Elizabeth and son-in-law Henry Coles, quarryman, in a property called No 4, Longsplatt. We might suppose that these were tenanted properties close to the site of Longsplatt Quarry (now called The Old Quarry). John was still there in 1911, described as an Old Age Pensioner, Quarriman (sic), at a time shortly after old age pensions had been introduced for over 70s in 1909. He died in 1911.

As well as a tradition of quarrying in the family, there were also several servicemen. Possibly this reflected the ups and downs of employment in the quarry trade. John’s brother George (born 1851) joined the Grenadier Guards (later Horse Guards) as a private on 20 March 1869 aged 18 years. He had previously worked as a blacksmith but was illiterate, unable to sign his name and instead had to make his mark. His lifestyle was described as exemplary and temperate (non-drinking). He served a total of 21 years in Windsor until his discharge on 1 April 1890, always a private. There were other military connections. John and Rosina’s son Thomas (born 1871) served as a private in the Wiltshire Regiment joining up in 1891 aged 18 and their grandchildren Reginald David and Frederick John were both killed in the First World War, as recorded below. Reginald and Frederick's elder brother George William Henry Gingell (1885 - 1963) also served in the army. Although wounded in the war, he survived and named his son Frederick Reginald George Gingell in 1918, obviously in honour of his two fallen brothers.

|

The Family at Prospect

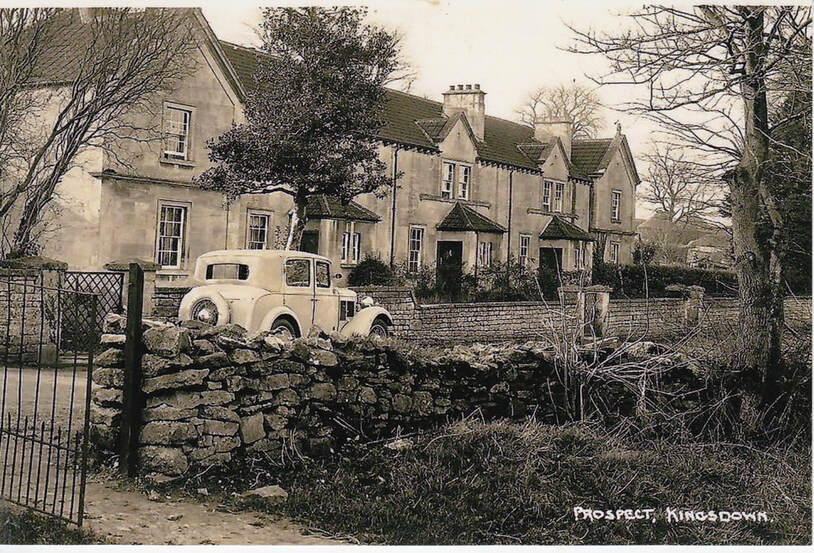

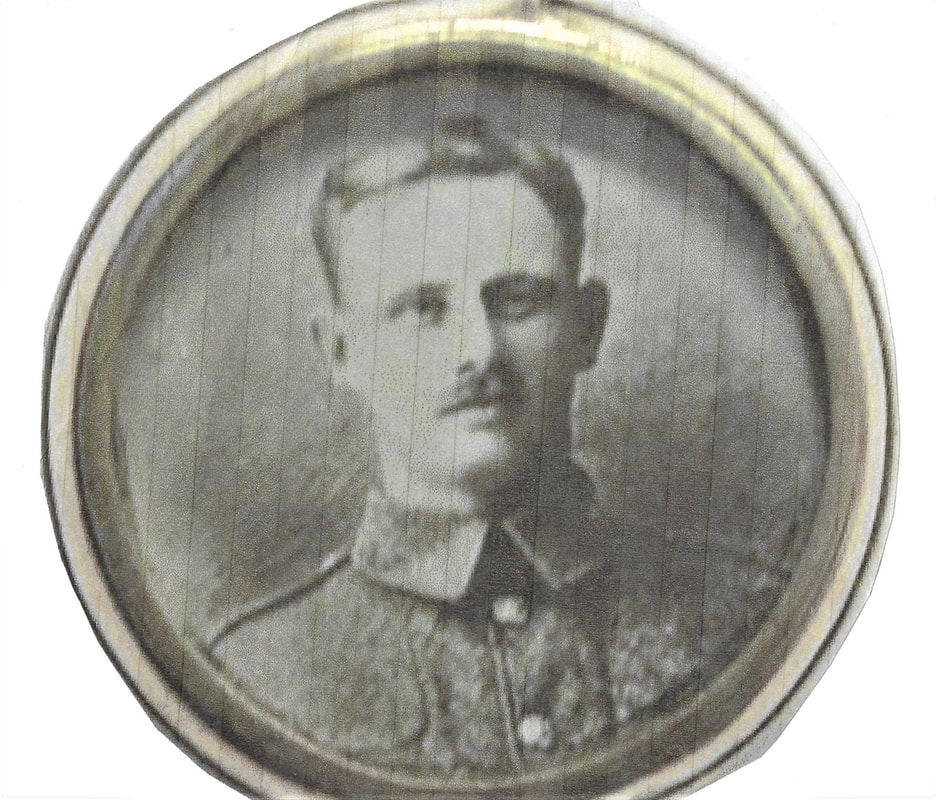

George William Gingell (my great grandfather’s brother) was married on 7 August 1884 to Alice Maud Smith (1863-11 August 1947), niece of Henry Smith, an ex-quarryman from Box Hill, who was described as innkeeper at the Quarryman’s Arms in the 1881 census. By 1901 George and Alice took a house at 2 Prospect Cottages just around the corner from George’s father at Longsplatt. George lived there until his death in 1930. He was a quarryman and the father of the two Gingells who are on the Box War Memorial, Reginald David Gingell and Frederick John Gingell. Reginald David Gingell in a memorial locket (courtesy Paula Pardoe) |

Reginald David Gingell (1889-1914) was the second son of George William and Alice Maud Gingell. He was a quarryman but there was insufficient work in the early 1900s and he joined the army in 1907. In the 1911 census he was described as a private in the 1st Wiltshire Regiment. He was killed on 18th October 1914 in the early days of the First World War, aged 25 years, serving as a Lance Corporal in the 9th (Queens Royal) Lancers. His body was buried at Sanctuary Wood Cemetery in Ypres, Belgium.

|

Frederick John Gingell (1892-1915) was the third son of George and Alice. He was a baker’s boy before joining the Royal Navy in January 1910. He served on several ships and was awarded the Messina Medal in 1908 for helping rescue victims of the earthquake and Tsunami that killed thousands in Messina in Sicily.

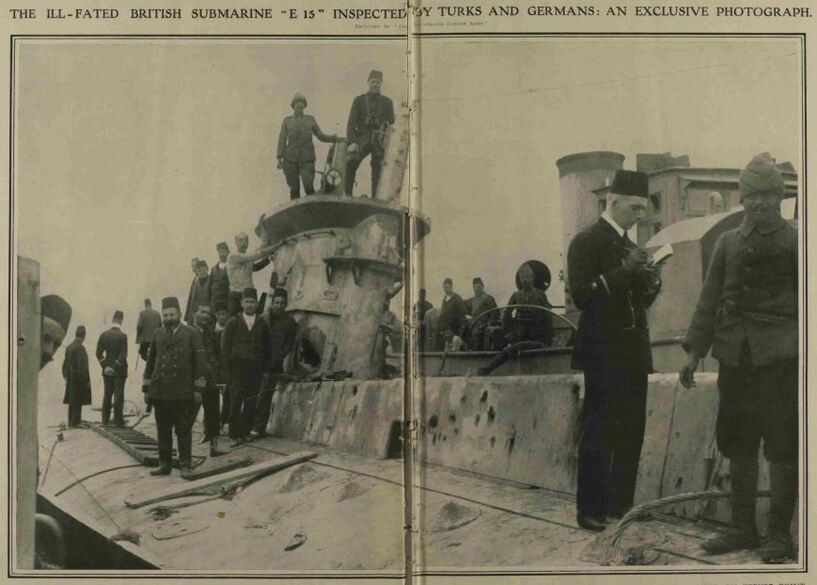

I am not sure when he moved over to submarines but he was serving on His Majesty’s Submarine E15 when it ran aground at Kephez Point in the Dardanelles on the 17th April 1915 early in the First World War.[2] Seven of the crew were subsequently killed by enemy bombardment, including Frederick. It is believed that he died from chlorine gas emitted from damaged batteries when the Turks fired on the submarine. Other members of the crew were taken prisoner and treated very badly by the Turks. The Turks captured the vessel, much to the consternation of the British. It was deemed to be imperative that the vessel did not fall into enemy hands and it was torpedoed and sunk on 18 April by friendly fire from British picket-boats to prevent the Turks from salvaging her. The headline photograph shows the Turks and Germans on board the damaged sub. Left: Frederick in uniform with his father George William Gingell (courtesy Paula Pardoe) |

|

It is especially poignant that Reginald and Frederick died within a short time of the commencement of the First World War, especially when their uncle served in Windsor and London for 21 years during which he never saw active service.

It was obviously a terrible tragedy for the family, as for many others. The pride evident in the photo of George William and Reginald was extinguished by grief at their loss and their mother, Alice Maud, always wore a locket with pictures of her fallen sons. The Gingells were a very longstanding Box family. The earliest mention we have found is of George Gingell born 1712 in Box, son of Isaac and Elioner Gingell. Another branch of the family, John and Elizabeth Gingell, had a son, also called George, born in Box in 1743. We get details of their status when this George was apprenticed to Robert Westcott, cordwainer (shoemaker) of Box in 1761 paying a premium of £10 (perhaps £2,000 in today’s values). George died in 1814 and was buried in Box Church. Other members of the family lived in the centre of Box in 1795 when the agent of the Northey family arranged the sale of the freehold of a property (possibly part of the house on the High Street now called Millers) which was then tenanted by Isaac Gingell.[3] Right: Alice Maud Gingell (courtesy Paula Pardoe) |

Paula’s story tells us much about the extent of the quarry trade in Box and the inter-connection of families involved in it. It also records the tragedy of recession in the industry and the consequences for young men without local opportunities who lost their lives in the First World War. Paula would love to hear more about her Box family if you have details.

Family Tree

William Gingell (1811-1873) was born at Lyneham and in 1839 married Elizabeth Head (1814-probably 1872). Children:

John (1839); Joseph (1841-1904); Mary (1844); Samuel (1846); David (1849); and George (1851) who served in the Horse Guards.

John (1839-1911) married Rosina Allen (1838-1888) in 1861. Children with Rosina:

George William (1863-1930); William (1864); Joseph John (1865), my grandfather; Elizabeth (1867); Thomas (1871) served as a private in the Wiltshire Regiment joining up in 1891 aged 18; Samuel (1878); Ela (1879); Eliza (1881); and Ethel (1884).

John married again in 1890 to Susan Nicks (b 1846), widow. No children from this marriage although Susan had children from her first marriage.

George William (1863-1930) married Alice Maud Smith (1863-1947) in 1884. Children:

George William (1886); Lillian MM (1887); Reginald David (1889-1914); Rosina, sometimes called Rosannah (1891); Frederick John (1892-1915); Elsie (1894); Ethel (1896); Flora (1898).

William Gingell (1811-1873) was born at Lyneham and in 1839 married Elizabeth Head (1814-probably 1872). Children:

John (1839); Joseph (1841-1904); Mary (1844); Samuel (1846); David (1849); and George (1851) who served in the Horse Guards.

John (1839-1911) married Rosina Allen (1838-1888) in 1861. Children with Rosina:

George William (1863-1930); William (1864); Joseph John (1865), my grandfather; Elizabeth (1867); Thomas (1871) served as a private in the Wiltshire Regiment joining up in 1891 aged 18; Samuel (1878); Ela (1879); Eliza (1881); and Ethel (1884).

John married again in 1890 to Susan Nicks (b 1846), widow. No children from this marriage although Susan had children from her first marriage.

George William (1863-1930) married Alice Maud Smith (1863-1947) in 1884. Children:

George William (1886); Lillian MM (1887); Reginald David (1889-1914); Rosina, sometimes called Rosannah (1891); Frederick John (1892-1915); Elsie (1894); Ethel (1896); Flora (1898).

References

[1] Inquest Report

[2] Illustrated London News, 3 July 1915

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 14 May 1795

[1] Inquest Report

[2] Illustrated London News, 3 July 1915

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 14 May 1795