A Wiltshire Lad

Geoff Bence

September 2014

Geoff Bence

September 2014

|

Geoff Bence and his brother, Nigel, were part of Box's shop community which straddled the period of the Second World War.

It was a time of great transition: from a self-sufficient village economy to the dawn of urban retail supermarkets outside the village. It was also a period of greater leisure and sports facilities that dominated the interest of youngsters in the 1950s. This is the story of Geoff and his family. |

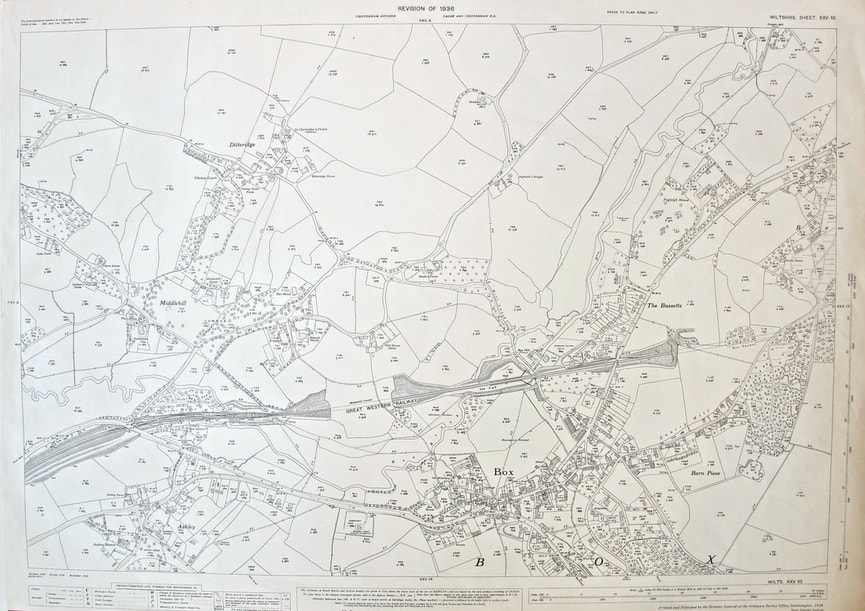

I was fortunate to have been born in a delightful part of the country, in the village of Box in Wiltshire, only six miles from Bath. It is best known for the Box Tunnel, on the main Bristol to London railway line constructed by Brunel.

My parents were Leslie Reginald Bence and Violet Mary Bence and I was the second of three sons - Nigel Thomas Bence being the eldest child born in 1920, me Geoffrey Charles Bence born in 1924 and Bryan Leslie Bence being the youngest brother 1924.

My parents were Leslie Reginald Bence and Violet Mary Bence and I was the second of three sons - Nigel Thomas Bence being the eldest child born in 1920, me Geoffrey Charles Bence born in 1924 and Bryan Leslie Bence being the youngest brother 1924.

Early Days

We lived at the Clift House at the top of Box Hill until I was four years of age when we moved to Lorne House in the village which dad had purchased. Despite being so young, I have some clear memories of the Clift. One memory was of the time I was crawling around on all fours and managed to get a tin tack in my knee, which dad removed with the aid of a pair of pliers. Another memory is of the mobile fish and chip van which came round. Dad would go out to the van and return with some chips in a small greaseproof bag for Nigel and I to have in bed; it was a huge treat. (Bryan had not arrived on the scene at that time.)

There was a large Welsh dresser in the kitchen at Clift. When Christmas was approaching I was told to look at a brown paper parcel on the top of the dresser each morning. The parcel increased in size each day, until Christmas Day when I was given the parcel and found it was a Teddy Bear. I still have it but, being over 80 years of age, it is looking the worse for wear.

When I was a baby I had a minor operation, performed by the local doctor who came from Corsham. That night mum found my cot was full of blood, so dad dashed to Corsham with his motor bike and sidecar to bring the doctor to attend to me. I have no recollection of a bathroom at The Clift, but I do remember being bathed in a large galvanised bath in front of a blazing fire.

We lived at the Clift House at the top of Box Hill until I was four years of age when we moved to Lorne House in the village which dad had purchased. Despite being so young, I have some clear memories of the Clift. One memory was of the time I was crawling around on all fours and managed to get a tin tack in my knee, which dad removed with the aid of a pair of pliers. Another memory is of the mobile fish and chip van which came round. Dad would go out to the van and return with some chips in a small greaseproof bag for Nigel and I to have in bed; it was a huge treat. (Bryan had not arrived on the scene at that time.)

There was a large Welsh dresser in the kitchen at Clift. When Christmas was approaching I was told to look at a brown paper parcel on the top of the dresser each morning. The parcel increased in size each day, until Christmas Day when I was given the parcel and found it was a Teddy Bear. I still have it but, being over 80 years of age, it is looking the worse for wear.

When I was a baby I had a minor operation, performed by the local doctor who came from Corsham. That night mum found my cot was full of blood, so dad dashed to Corsham with his motor bike and sidecar to bring the doctor to attend to me. I have no recollection of a bathroom at The Clift, but I do remember being bathed in a large galvanised bath in front of a blazing fire.

The small steep garden at the rear of The Clift led up to the stone quarry. Stone was extracted and placed on a wagon which ran on railway lines down across a field next to the road, under the bridge. Then it went behind the last house on the left (where barns are now) and in front of the row of cottages. Nigel lived in the last house at one time. Then it went to The Wharf near the entrance of Box Tunnel where it was loaded onto the main railway. A similar method of transporting stone from the hillside down to the railway line took place at a number of quarries, and it was known as a tramcar.

It was curious seeing the iron carriages sent up and down without horses; and by the side of machinery the vehicles change their positions midway, the full one running down to the Wharf by the main railway line, and the empty one making its way to the top to receive the next load.

|

The Family Business

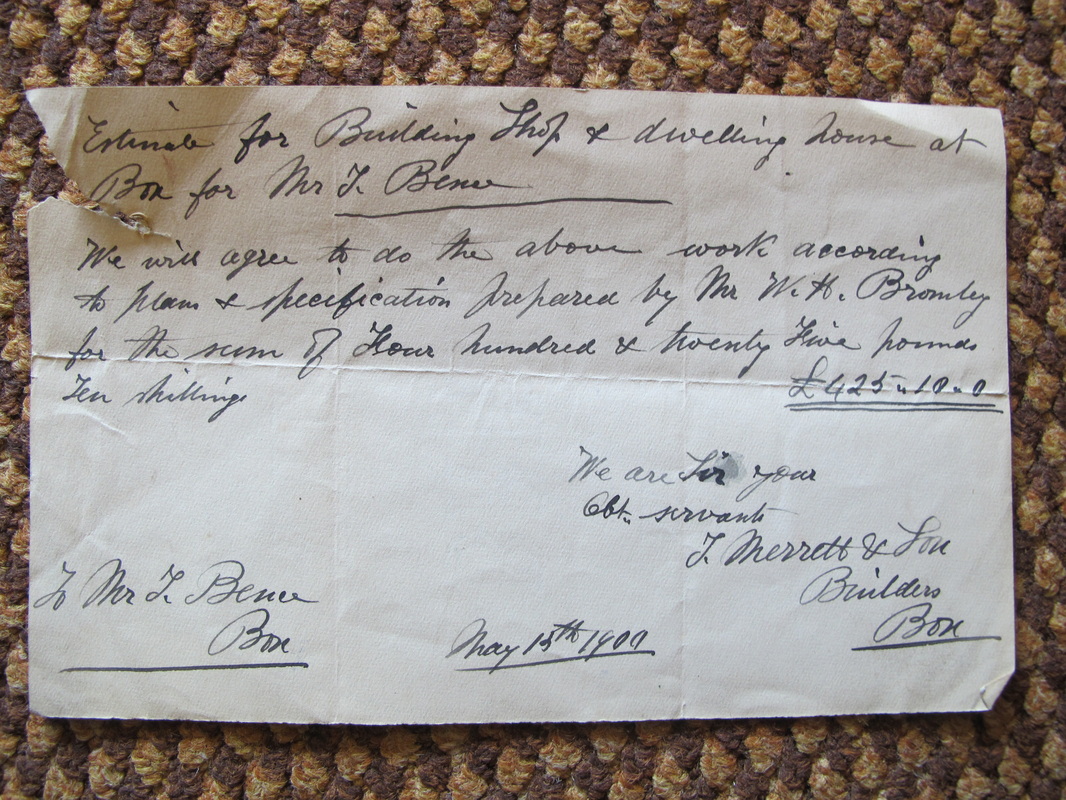

My grandfather, Thomas Bence and grandmother, Florence Bence (nee lng), had built up a business in the Market Place, Box. Grandmother started it in the front room of Coleridge House. The business prospered and grandfather, who was farming, joined her in the business. In 1900 they built a new shop, with living accommodation over, on waste land at the corner of the Market Place facing the Chequers Inn. I remember the Market Place being called Frog Street in those days. |

|

The

shop cost £425.10s.0d and it was built by T Merrett & Son. Thomas Merrett

was a local builder; remarkably enough he was the grandfather of my wife,

Barbara.

In those days they employed their own tradesmen, plumbers, electricians and carpenters, and they had big workshops and a yard, opposite the Post office where Vine Court now stands. There was a smithy there run by Mr Clarke, the blacksmith. I have the handwritten specifications relating to the building, signed by Thomas Bence and Thomas Merrett. |

One side of the shop was groceries and the other was more like a mini department store selling clothes, linoleum and radios. The main business was as a drapers. We had a stack of stuff there. Before the war there was a great demand for overalls from the quarrymen: aprons, overalls and boots were in constant demand.

Life at Home

Dad grew up in Box, going first to Box School and then to King Edwards School in Bath. On leaving school, he went as an apprentice to a department store, Parsons and Hart, in Andover, where he lived in, the intention being for him to run the drapery side of the business on his return. When the 1914-18 war came dad failed the medical for the Army and in 1918 he was a victim of the Spanish flu, which was said to have killed more people than the war.

Dad and mum married on April 31st 1919, when dad took on the lease of the Clift House, Box Hill. Nigel and I were both born there but Bryan did not arrive on the scene until 1929 after we had moved to Lorne House. There was no electricity at the Clift, lighting was by oil lamps, and I remember mum took great pride in keeping them spotlessly clean. I think cooking was done on a paraffin stove as there was no gas or electricity.

Dad had a great sense of humour. As a child he and his friends would stare up in the sky, which always encouraged passers-by to do the same, even though there was nothing there. He was full of stories: he saw Buffalo Bill Cody, the famous Wild West American, in the early 1900s. He always loved children and we used to have lots of children round for birthday parties. He used to play party games with us; in one trick he encouraged the children to run their fingers round the bottom of saucers and then rub their noses. He didn't tell them that he had blackened their saucers with a candle flame, only his was clean. So they went home very dirty. My wife Barbara came to the parties. She was an only child, rather a timid little girl, and her mother was very prim and proper. I don't know what they made of all father's antics.

My father had a Sunbeam motorcycle and sidecar, formerly owned by grandfather. The sidecar had two seats, a main passenger seat with a small seat behind. When dad needed to transport the whole family, mum was in the main passenger seat, I was in the small seat behind her and Nigel was on the pillion seat of the motorcycle behind dad.

Dad grew up in Box, going first to Box School and then to King Edwards School in Bath. On leaving school, he went as an apprentice to a department store, Parsons and Hart, in Andover, where he lived in, the intention being for him to run the drapery side of the business on his return. When the 1914-18 war came dad failed the medical for the Army and in 1918 he was a victim of the Spanish flu, which was said to have killed more people than the war.

Dad and mum married on April 31st 1919, when dad took on the lease of the Clift House, Box Hill. Nigel and I were both born there but Bryan did not arrive on the scene until 1929 after we had moved to Lorne House. There was no electricity at the Clift, lighting was by oil lamps, and I remember mum took great pride in keeping them spotlessly clean. I think cooking was done on a paraffin stove as there was no gas or electricity.

Dad had a great sense of humour. As a child he and his friends would stare up in the sky, which always encouraged passers-by to do the same, even though there was nothing there. He was full of stories: he saw Buffalo Bill Cody, the famous Wild West American, in the early 1900s. He always loved children and we used to have lots of children round for birthday parties. He used to play party games with us; in one trick he encouraged the children to run their fingers round the bottom of saucers and then rub their noses. He didn't tell them that he had blackened their saucers with a candle flame, only his was clean. So they went home very dirty. My wife Barbara came to the parties. She was an only child, rather a timid little girl, and her mother was very prim and proper. I don't know what they made of all father's antics.

My father had a Sunbeam motorcycle and sidecar, formerly owned by grandfather. The sidecar had two seats, a main passenger seat with a small seat behind. When dad needed to transport the whole family, mum was in the main passenger seat, I was in the small seat behind her and Nigel was on the pillion seat of the motorcycle behind dad.

Lorne House

We moved to Lorne House in 1928. The agent who dealt with the purchase of Lorne House was Charles Oatley, and I believe dad paid £500 for it. Lorne House is a large semi-detached house with five bedrooms on the first floor and a bathroom. The ground, floor had a dining room, a drawing room, lounge and a kitchen. In the basement, which was reached by going down a stone staircase, there were two large rooms, a cellar and a coal house. One room was used as the washroom where mum did the laundry and the other room was called the charging room, because dad had the apparatus to re-charge accumulators which provided the power for wireless sets in those days.

The cellar, being below ground level, was always at a nice even temperature. There were stone shelves all the way round the room which were very convenient for placing dishes of food to keep for a few days. This was particularly useful at Christmas when mum made trifle etc shortly before the festivities. Another use of the cellar was for preserving eggs. There were some large glass tanks filled with waterglass (isinglass) which had the effect of sealing the eggs to preserve them. In those days eggs were in short supply during the winter months, hence the need to preserve them, when they were plentiful.

There was a large sink in the laundry room, and a gas boiler in which the clothes were washed. The boiler was also used when mum made the Christmas puddings and a number were made each year. Only one, which was for Christmas Day, had sixpences wrapped in greaseproof paper inside it. I kept asking for more until I had a slice with a sixpence in it. Each year it became a ritual for mum to say, Not as good as last year.

Rather surprisingly, there was a large pump in the washroom which drew water up from a well. The pump needed to be primed by pouring water down it, before it would function. I remember how beautifully cool the water was, particularly noticeable on a hot summer day. The back door, leading out from the basement, opened on to a small courtyard; along to the left was an outdoor toilet and off to the left of that was the ash pit where ashes from the fires were deposited. We were told that when the Rev Awdry lived at Lorne House he had his model railway set up in the greenhouse. It was a good size and suitable for the hobby.

Soon after we moved to Lorne House dad became the proud owner of an Austin Seven car. On most Sunday afternoons visits were made to gran Daniell and aunt Olive at Bathford. On other occasions we would visit uncle Charles and family at his farm, or to aunt Floss and uncle Bob at Honeybrook Farm, Slaughterford. I left school early to help dad in the shop, until I went into the army in 1942.

We moved to Lorne House in 1928. The agent who dealt with the purchase of Lorne House was Charles Oatley, and I believe dad paid £500 for it. Lorne House is a large semi-detached house with five bedrooms on the first floor and a bathroom. The ground, floor had a dining room, a drawing room, lounge and a kitchen. In the basement, which was reached by going down a stone staircase, there were two large rooms, a cellar and a coal house. One room was used as the washroom where mum did the laundry and the other room was called the charging room, because dad had the apparatus to re-charge accumulators which provided the power for wireless sets in those days.

The cellar, being below ground level, was always at a nice even temperature. There were stone shelves all the way round the room which were very convenient for placing dishes of food to keep for a few days. This was particularly useful at Christmas when mum made trifle etc shortly before the festivities. Another use of the cellar was for preserving eggs. There were some large glass tanks filled with waterglass (isinglass) which had the effect of sealing the eggs to preserve them. In those days eggs were in short supply during the winter months, hence the need to preserve them, when they were plentiful.

There was a large sink in the laundry room, and a gas boiler in which the clothes were washed. The boiler was also used when mum made the Christmas puddings and a number were made each year. Only one, which was for Christmas Day, had sixpences wrapped in greaseproof paper inside it. I kept asking for more until I had a slice with a sixpence in it. Each year it became a ritual for mum to say, Not as good as last year.

Rather surprisingly, there was a large pump in the washroom which drew water up from a well. The pump needed to be primed by pouring water down it, before it would function. I remember how beautifully cool the water was, particularly noticeable on a hot summer day. The back door, leading out from the basement, opened on to a small courtyard; along to the left was an outdoor toilet and off to the left of that was the ash pit where ashes from the fires were deposited. We were told that when the Rev Awdry lived at Lorne House he had his model railway set up in the greenhouse. It was a good size and suitable for the hobby.

Soon after we moved to Lorne House dad became the proud owner of an Austin Seven car. On most Sunday afternoons visits were made to gran Daniell and aunt Olive at Bathford. On other occasions we would visit uncle Charles and family at his farm, or to aunt Floss and uncle Bob at Honeybrook Farm, Slaughterford. I left school early to help dad in the shop, until I went into the army in 1942.

Cricket

Dad was very keen on cricket and we practised in the courtyard. Wickets were marked out on the toilet door and dad would bowl to us and give instructions. He had a problem with me because I would insist on holding the bat incorrectly, with the right hand higher on the bat handle than the left hand. Eventually, dad said, If you must hold it that way, turn round and bat left handed. By doing that the hands were in the right position and I have been left handed ever since, but I am right handed for other things.

We also practised cricket on the lawn which got dad into trouble, because there was a large greenhouse at the end of the lawn. We always tried to keep the ball on the ground but, unfortunately, on occasions a window in the greenhouse would be broken. Mum would be working in the kitchen and, hearing the crash, would open the window to give dad a ticking off. The greenhouse was mum's domain; she grew delicious tomatoes in it. Each spring a visit was made to Mr Gaisford at Colerne, where he had a nursery and mum purchased the tomato plants there.

Nigel and I and most of our friends played cricket in our youth.

Dad was very keen on cricket and we practised in the courtyard. Wickets were marked out on the toilet door and dad would bowl to us and give instructions. He had a problem with me because I would insist on holding the bat incorrectly, with the right hand higher on the bat handle than the left hand. Eventually, dad said, If you must hold it that way, turn round and bat left handed. By doing that the hands were in the right position and I have been left handed ever since, but I am right handed for other things.

We also practised cricket on the lawn which got dad into trouble, because there was a large greenhouse at the end of the lawn. We always tried to keep the ball on the ground but, unfortunately, on occasions a window in the greenhouse would be broken. Mum would be working in the kitchen and, hearing the crash, would open the window to give dad a ticking off. The greenhouse was mum's domain; she grew delicious tomatoes in it. Each spring a visit was made to Mr Gaisford at Colerne, where he had a nursery and mum purchased the tomato plants there.

Nigel and I and most of our friends played cricket in our youth.

We had some good fast bowlers after the war, E Tye was one of them. HH (Bunno) Sawyer was very tall (all arms and legs) and a good cricketer. He used to take an extremely long run-up at 45 degrees to the wicket, then almost stop and deliver rather slow bowls. He always did very well.

When we were kids they used to put seats outside the old pavilion (long gone now) and we used to play about on the seats until Mr McIlwraith chased us off. There was a tea hut next to the pavilion where my wife and all the ladies used to prepare the food. It was built against a stone wall with a corrugated iron roof. Every so often the ball would land on the roof and all the spiders and webs would come down on the sandwiches. The ladies used to do the scoring. The smell of all the linseed oil seems an age ago now. There is still a Box Cricket Club but it plays in a lower division than it used to against teams like Corsham Thirds!

When we were kids they used to put seats outside the old pavilion (long gone now) and we used to play about on the seats until Mr McIlwraith chased us off. There was a tea hut next to the pavilion where my wife and all the ladies used to prepare the food. It was built against a stone wall with a corrugated iron roof. Every so often the ball would land on the roof and all the spiders and webs would come down on the sandwiches. The ladies used to do the scoring. The smell of all the linseed oil seems an age ago now. There is still a Box Cricket Club but it plays in a lower division than it used to against teams like Corsham Thirds!

My Brother Nigel

My brother lived for cricket; he was a very good cricketer, better than I was, a classical batsman. It was his religion; he went all round the world watching whether he could afford it or not. When he left school he went to London to work for I&R Morley, the hosiery firm. Charles Morley, a director of the firm, lived at Shockerwick House at that time. Father and Nigel went down to see him to get Nigel the position. He was there when the war started and then he came home until he was called up into the air force. He was a radio mechanic in the war. There was always a joke between us because he served all the time in the Scilly Isles whereas I went all round the Far East. When I pulled his leg about it he used to say It was a terrible crossing.

My brother lived for cricket; he was a very good cricketer, better than I was, a classical batsman. It was his religion; he went all round the world watching whether he could afford it or not. When he left school he went to London to work for I&R Morley, the hosiery firm. Charles Morley, a director of the firm, lived at Shockerwick House at that time. Father and Nigel went down to see him to get Nigel the position. He was there when the war started and then he came home until he was called up into the air force. He was a radio mechanic in the war. There was always a joke between us because he served all the time in the Scilly Isles whereas I went all round the Far East. When I pulled his leg about it he used to say It was a terrible crossing.

|

After the war he went back

to the shop and started repairing radios and then later televisions when they

started, and other electrical apparatus. He did this upstairs in the shop. When

dad died he took over the little shop and the house with the lovely shell porch

in the Market Place, Frogmore House. Later he went to work for a firm at

Westbury repairing televisions.

World War Two On the outbreak of the 1939-45 war there was a fear of air raids. A warning siren was situated in Merrett's yard, opposite the Post Office. The cellar was considered a safe place to be in the event of an air raid, so when the siren was sounded, any neighbours who wished to shelter in the cellar were invited to come. A few did, but most preferred to stay in their beds, and as no air raids materialised, this precaution soon came to an end. Left: Frogmore House (Photo CMP) |

In the early days of the war dad was in the Special Police when part of his duties was to guard Box Tunnel. It involved going into the Tunnel which dad found quite daunting, it being very eerie in the dark with the sound of water dripping from the roof. When a train came through he had to quickly get into one of the alcoves provided for the purpose. Steam trains then of course, so one had to contend with the smoke, the noise and the drips. Dad was the sergeant and Alf Lambert was the Superintendent. After a spell of duty in the Tunnel they would return to Lorne House for refreshments. Nigel had a small barrel of beer in the cellar and he maintained that Uncle Alf drunk the lot as dad never drank beer.

My mother was a Red Cross nurse in the First World War and when Nigel and I were called up in the Second War she was terribly upset thinking that we would come back with injuries similar to those she had to treat at Corsham Hospital. Fortunately we didn't.

Dad was an only child so there were no aunts or uncles on his side. He always said that he looked upon his cousin, Reg Ings, as a brother, and they remained firm friends all their lives. He was a Territorial soldier, being a member of the North Somerset Yeomanry. There were stables at the end of his garden where he kept his horse. When he retired and sold his house and business, he had the stable block converted into a nice house where he spent the rest of his days.

Dad always said that Reg was the only man he knew who wanted a war, being so keen on the military life, despite the fact that he was the most gentle kind man one could wish to meet. I think it was the love of the horses, rather than any warlike activity, that attracted him. When the 1939-45 war broke out, uncle Reg failed the medical which was a great disappointment. He kept trying to join and in the end he was accepted for non combative duties. Being a Regimental Sergeant-Major, he was put in charge of prisoner of war camps in North Africa.

My mother was a Red Cross nurse in the First World War and when Nigel and I were called up in the Second War she was terribly upset thinking that we would come back with injuries similar to those she had to treat at Corsham Hospital. Fortunately we didn't.

Dad was an only child so there were no aunts or uncles on his side. He always said that he looked upon his cousin, Reg Ings, as a brother, and they remained firm friends all their lives. He was a Territorial soldier, being a member of the North Somerset Yeomanry. There were stables at the end of his garden where he kept his horse. When he retired and sold his house and business, he had the stable block converted into a nice house where he spent the rest of his days.

Dad always said that Reg was the only man he knew who wanted a war, being so keen on the military life, despite the fact that he was the most gentle kind man one could wish to meet. I think it was the love of the horses, rather than any warlike activity, that attracted him. When the 1939-45 war broke out, uncle Reg failed the medical which was a great disappointment. He kept trying to join and in the end he was accepted for non combative duties. Being a Regimental Sergeant-Major, he was put in charge of prisoner of war camps in North Africa.

|

Getting Married

In those days, you went and asked the father for permission to get married. When the time came, Barbara and her mother pushed me into the sitting room with the old chap, shut the door and they listened outside. I said we were thinking about getting married. You would never believe that Barbara's father thought we were too young: Barbara was 30 and I was 25 and we had both served through the war. But her mother was for it and we were old enough to get married anyway, so we went ahead. |

Barbara was in the WAAF (Women's Auxiliary Air Force) in the war, a drill sergeant in charge of making the young girls fitter (and of getting them out of bed in the morning). I always pulled her leg afterwards, saying that she never handed her stripes in.

I was trained as a wireless operator with the Royal Signals and then I was selected to work for the SOE (Special Operations Executive), which dealt with enemy occupied countries. I was in the far east for three years and right at the end, in Singapore, I had peritonitis, which was often a killer in those days. Mum went straight down to Box Church and prayed for me. I was in hospital a long time and unable to eat or drink anything. When I began to recover they gave me an ice cube to suck, then later a cup of Horlicks, it tasted wonderful. The country had just been retaken by the Allies and was all in ruins.

I was still in hospital at the end of the war and overdue to be demobbed but the doctor said I was too ill to travel. A hospital ship came into port and the doctor came rushing back in and said if I signed papers to say that it was my decision to travel then I could go home. So they carried me on board on a stretcher and put me to bed. The ship sailed to Rangoon, Madras, Aden, Port Suez picking up invalids. When we arrived back at Southampton I had recovered and walked back on land where my mum was waiting for me. It was so good to be back.

After the war, I came back to help in my father's shop. Dad was always overworked and I just wanted to help him. When Dad retired, I carried it on but when supermarkets came in it got harder and harder. In the end I decided to call it a day because we weren't making any money at all. We decided to convert the premises into flats. I did some of the navvying work. After some bad tenants we decided to sell the whole property. My brother, Nigel, had his own shop further along the Market Place and a house behind it.

My aunt Olive moved into Lorne House to look after my mother, Violet, when she was widowed. At one stage Nigel and Joan moved into the house as well but three ladies in the kitchen proved to be too many for Nigel and he and Joan moved out.

Grandfather Bence had a brother, uncle Bob, who was quite a character. When he was a lad he was caught poaching rabbits; knowing he was in trouble he ran off to join the Army. The first time he came home on leave he came face to face with Squire Walmsley, who owned the land, coming along on his horse. The Squire said, l see you have joined the Army, Bence, and gave him a shilling. I doubt the Squire knew anything about the poaching. I think uncle Bob reached the rank of Regimental Sergeant-Major.

I was trained as a wireless operator with the Royal Signals and then I was selected to work for the SOE (Special Operations Executive), which dealt with enemy occupied countries. I was in the far east for three years and right at the end, in Singapore, I had peritonitis, which was often a killer in those days. Mum went straight down to Box Church and prayed for me. I was in hospital a long time and unable to eat or drink anything. When I began to recover they gave me an ice cube to suck, then later a cup of Horlicks, it tasted wonderful. The country had just been retaken by the Allies and was all in ruins.

I was still in hospital at the end of the war and overdue to be demobbed but the doctor said I was too ill to travel. A hospital ship came into port and the doctor came rushing back in and said if I signed papers to say that it was my decision to travel then I could go home. So they carried me on board on a stretcher and put me to bed. The ship sailed to Rangoon, Madras, Aden, Port Suez picking up invalids. When we arrived back at Southampton I had recovered and walked back on land where my mum was waiting for me. It was so good to be back.

After the war, I came back to help in my father's shop. Dad was always overworked and I just wanted to help him. When Dad retired, I carried it on but when supermarkets came in it got harder and harder. In the end I decided to call it a day because we weren't making any money at all. We decided to convert the premises into flats. I did some of the navvying work. After some bad tenants we decided to sell the whole property. My brother, Nigel, had his own shop further along the Market Place and a house behind it.

My aunt Olive moved into Lorne House to look after my mother, Violet, when she was widowed. At one stage Nigel and Joan moved into the house as well but three ladies in the kitchen proved to be too many for Nigel and he and Joan moved out.

Grandfather Bence had a brother, uncle Bob, who was quite a character. When he was a lad he was caught poaching rabbits; knowing he was in trouble he ran off to join the Army. The first time he came home on leave he came face to face with Squire Walmsley, who owned the land, coming along on his horse. The Squire said, l see you have joined the Army, Bence, and gave him a shilling. I doubt the Squire knew anything about the poaching. I think uncle Bob reached the rank of Regimental Sergeant-Major.

|

He served in India and had a number of tales to tell. The one I remember well is how he was a long way out of camp on his own, and came face to face with a pack of monkeys. Knowing that if he turned his back on them they would tear him to pieces, he walked backwards all the way back to camp.

In later years uncle Bob became what was known as the Master of the Workhouse, establishments where down and outs were sent to be looked after. I remember visiting one and thinking what a sad place it was. The workhouse at Chippenham is now St Andrew's Hospital, very different to the workhouse days. Conclusion A few years ago my dear mum was taken there, when in her nineties, and she thought she was in the workhouse. She said, Uncle Bob was the Master here, young Bob (his son) was born here, and now I am in the workhouse! I could not get her out of there quickly enough. Poor mum! Mum lived to be 101 and when she had a visitor on her hundredth birthday she said, I had a very nice card from my friend Liz. Who was that? She lives in Buckingham Palace. Mum had a wonderful sense of humour, right to the end. |

Family Tree

1. Thomas Bence (1832 - ) married Sarah Gunning (1847 - ) where they farmed a small holding of 50 acres at Eastrip, Colerne, employing one man. Children: Thomas (b 1868); Mary (b 1872); Emma (1874); John (b 1877); Henry (b 1880); Robert (b 1883); Alice (b 1885); and Isabella (b 1888). In 1881 Sarah's relative John Gunning, aged 80, annuitant, lived with them.

2. Thomas Bence (1868 - 1957) born Wraxall married Florence Gertrude Ings (1868 - ) of Kilmington.

In 1901 they lived at Coleridge House, the Market Place, and in 1911 were listed in the Market Place in 6 rooms.

Thomas died 11 September 1957 at Lorne House leaving £7,234.17s.5d to Leslie Reginald Bence, Master grocer

Child: Leslie Reginald Bence (1896 - 1983)

3. Leslie Reginald Bence (1896 - 1983) married Violet M Daniell

In 1911 Leslie was working as an Apprentice Draper for Parsons & Hart, Waterloo House, Andover as one of 20 drapery employees. Children: Nigel Thomas Bence (1920 - 2006); Geoffrey Charles Bence(1924 - 2018); Bryan Leslie Bence (b 1929)

4. Nigel Bence married Joan Swift

Children: Carol; Kay; Mary

5. Geoff Bence married Barbara Merrett

Children: Julie; Judy

1. Thomas Bence (1832 - ) married Sarah Gunning (1847 - ) where they farmed a small holding of 50 acres at Eastrip, Colerne, employing one man. Children: Thomas (b 1868); Mary (b 1872); Emma (1874); John (b 1877); Henry (b 1880); Robert (b 1883); Alice (b 1885); and Isabella (b 1888). In 1881 Sarah's relative John Gunning, aged 80, annuitant, lived with them.

2. Thomas Bence (1868 - 1957) born Wraxall married Florence Gertrude Ings (1868 - ) of Kilmington.

In 1901 they lived at Coleridge House, the Market Place, and in 1911 were listed in the Market Place in 6 rooms.

Thomas died 11 September 1957 at Lorne House leaving £7,234.17s.5d to Leslie Reginald Bence, Master grocer

Child: Leslie Reginald Bence (1896 - 1983)

3. Leslie Reginald Bence (1896 - 1983) married Violet M Daniell

In 1911 Leslie was working as an Apprentice Draper for Parsons & Hart, Waterloo House, Andover as one of 20 drapery employees. Children: Nigel Thomas Bence (1920 - 2006); Geoffrey Charles Bence(1924 - 2018); Bryan Leslie Bence (b 1929)

4. Nigel Bence married Joan Swift

Children: Carol; Kay; Mary

5. Geoff Bence married Barbara Merrett

Children: Julie; Judy