|

Evacuees in Box

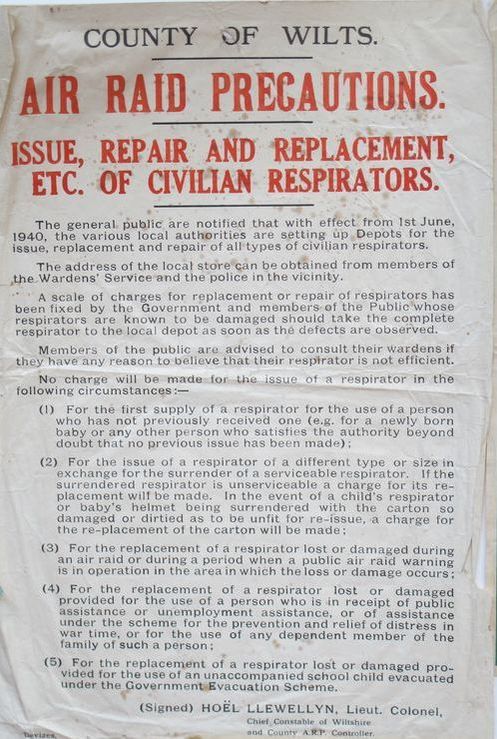

Alan Payne January 2018 The Village in 1940 We have a good King and Queen, a wise and trusted Prime Minister, a united people at home, and a loyal Empire ... We are thankful for the high state of efficiency of the Forces of our King, which are growing stronger every day. Rev Arthur F Maltin Fearing a quarter of a million air raid fatalities in the first week of war, the government arranged the evacuation of children from vulnerable areas in London to rural locations such as Box, when in the space of four days in September 1939 in total nearly 9,000 mothers, children and babies under five years left the capital.[1] The children arrived by train with small suitcases containing a change of underwear, pullover, tooth brush and a gas mask.[2] Ninety-six child evacuees came to Box village.[3] Vicar Arthur Maltin wrote One complete school and part of another found their way to Box, namely St Mary Abbots (Kensington) and Old Oak School (Ealing).[4] Right: Public air raid notice (courtesy Eric Callaway) |

Janice Cannings Remembers the Evacuees' Arrival

I remember going to school in the war. One day we all had to go back home because evacuees were brought down from London. They were all in the front playground with their gas masks over their shoulders. The ladies of the village were outside picking which children they would take in. Those who were the most attractive and cleanest were soon taken.

I remember going to school in the war. One day we all had to go back home because evacuees were brought down from London. They were all in the front playground with their gas masks over their shoulders. The ladies of the village were outside picking which children they would take in. Those who were the most attractive and cleanest were soon taken.

Welcome to Box

The number was too large to be easily integrated with 168 Box schoolchildren so the London County Council rented three extra rooms in the Methodist School to take the overspill. Box was involved from the outset and the first maintenance payments were made on 12 September 1939 at the Methodist School Room to Box carers and the teachers that accompanied the children.[5] Responsible for organising billeting in Box were Miss Locock, Mrs Strode and Mrs Perry as well as Rev Arthur Maltin and his wife, Margaret.

Christmas 1939 was extremely hard for the evacuated children away from home for the first time and missing their families. To help, the GWR ran a special train, over-crowded and extra-long, to bring the London families to Bath and the area to see their children.[6] The total number of visitors to the Bath area was 540 adults who were bussed out of the city to their children's accommodation in Box and other villages. The adults stayed the whole day returning to London in pitch darkness in the blackout at 7.25pm. The visit was followed by a January party in the Bingham Hall with a sumptuous tea, crackers and sweets.[7]

A pantomime of Cinderella was put on in the Infant School on 13 February for the Vackies, performed by ladies of the village with great success.[8] The special trains continued to bring parents to visit the evacuees and GWR ran an express on 3 March 1940 which actually stopped at Mill Lane Halt.[9]

Returning to London

The children had obviously suffered a considerable shock coming to rural Wiltshire and worse followed when the weather turned extremely cold.[10] The night of 22 December showed a temperature of minus 7 degrees and on 30 December minus 12 degrees. This continued into January and on 9 January a record was reached with minus 27.3 degrees in Henrietta Park, Bath. The Box Brook froze over in the lowest temperature since records began.

The London schools started to reopen and during the period of the Phoney War homesick evacuee children started to return to their parents. By the end of January 1940, a third of the children had gone back. In February the headmaster of Box School,

HA Druett, and his wife celebrated their Silver Wedding Anniversary. They had cared for an evacuee girl, Dorothy, who had returned home but obviously a special bond had been formed and she returned for their day and presented them with a silver sixpence.[11]

Second Wave

Box was involved in the evacuation of more children from London in May and June 1940 when aerial attacks on the West of England caused huge alarm in local newspapers.[12] Three people were killed by bombs but articles focussed on playing down the seriousness A rabbit and a silver plover were the only victims of a bomber, a bull broke loose and eight enemy aircraft were brought down with no mention of Allied losses.

The Waifs and Strays Society set up local provision for the plight of the bombed babies of London at its hostels in Bath, Batheaston and Box.[13] In the absence of bedding supplies, the children slept on stretchers at first and an appeal was made for clothing for them. Some of the evacuees had been picked up from the debris of their homes, others had been sent away from the battle front.

Thereafter there was a steady trickle of evacuated children to live in Box. By the end of the war there were still twelve London County Council children in the village.[14] One of them, Peter Steel had arrived in 1941 from St Mary Abbots and stayed with

Mr and Mrs Victor Milsom. He had integrated into the church choir and as a scout patrol leader before he returned to London to take up an apprenticeship in the building trade. Peter's parents wrote to Rev Maltin about his time We shall never forget you and all at Box who have been so kind to him, and us when we paid a visit to you. We should like especially to express our thanks to

Mr and Mrs Victor Milsom who built him up to the fine boy he is today.[15]

The number was too large to be easily integrated with 168 Box schoolchildren so the London County Council rented three extra rooms in the Methodist School to take the overspill. Box was involved from the outset and the first maintenance payments were made on 12 September 1939 at the Methodist School Room to Box carers and the teachers that accompanied the children.[5] Responsible for organising billeting in Box were Miss Locock, Mrs Strode and Mrs Perry as well as Rev Arthur Maltin and his wife, Margaret.

Christmas 1939 was extremely hard for the evacuated children away from home for the first time and missing their families. To help, the GWR ran a special train, over-crowded and extra-long, to bring the London families to Bath and the area to see their children.[6] The total number of visitors to the Bath area was 540 adults who were bussed out of the city to their children's accommodation in Box and other villages. The adults stayed the whole day returning to London in pitch darkness in the blackout at 7.25pm. The visit was followed by a January party in the Bingham Hall with a sumptuous tea, crackers and sweets.[7]

A pantomime of Cinderella was put on in the Infant School on 13 February for the Vackies, performed by ladies of the village with great success.[8] The special trains continued to bring parents to visit the evacuees and GWR ran an express on 3 March 1940 which actually stopped at Mill Lane Halt.[9]

Returning to London

The children had obviously suffered a considerable shock coming to rural Wiltshire and worse followed when the weather turned extremely cold.[10] The night of 22 December showed a temperature of minus 7 degrees and on 30 December minus 12 degrees. This continued into January and on 9 January a record was reached with minus 27.3 degrees in Henrietta Park, Bath. The Box Brook froze over in the lowest temperature since records began.

The London schools started to reopen and during the period of the Phoney War homesick evacuee children started to return to their parents. By the end of January 1940, a third of the children had gone back. In February the headmaster of Box School,

HA Druett, and his wife celebrated their Silver Wedding Anniversary. They had cared for an evacuee girl, Dorothy, who had returned home but obviously a special bond had been formed and she returned for their day and presented them with a silver sixpence.[11]

Second Wave

Box was involved in the evacuation of more children from London in May and June 1940 when aerial attacks on the West of England caused huge alarm in local newspapers.[12] Three people were killed by bombs but articles focussed on playing down the seriousness A rabbit and a silver plover were the only victims of a bomber, a bull broke loose and eight enemy aircraft were brought down with no mention of Allied losses.

The Waifs and Strays Society set up local provision for the plight of the bombed babies of London at its hostels in Bath, Batheaston and Box.[13] In the absence of bedding supplies, the children slept on stretchers at first and an appeal was made for clothing for them. Some of the evacuees had been picked up from the debris of their homes, others had been sent away from the battle front.

Thereafter there was a steady trickle of evacuated children to live in Box. By the end of the war there were still twelve London County Council children in the village.[14] One of them, Peter Steel had arrived in 1941 from St Mary Abbots and stayed with

Mr and Mrs Victor Milsom. He had integrated into the church choir and as a scout patrol leader before he returned to London to take up an apprenticeship in the building trade. Peter's parents wrote to Rev Maltin about his time We shall never forget you and all at Box who have been so kind to him, and us when we paid a visit to you. We should like especially to express our thanks to

Mr and Mrs Victor Milsom who built him up to the fine boy he is today.[15]

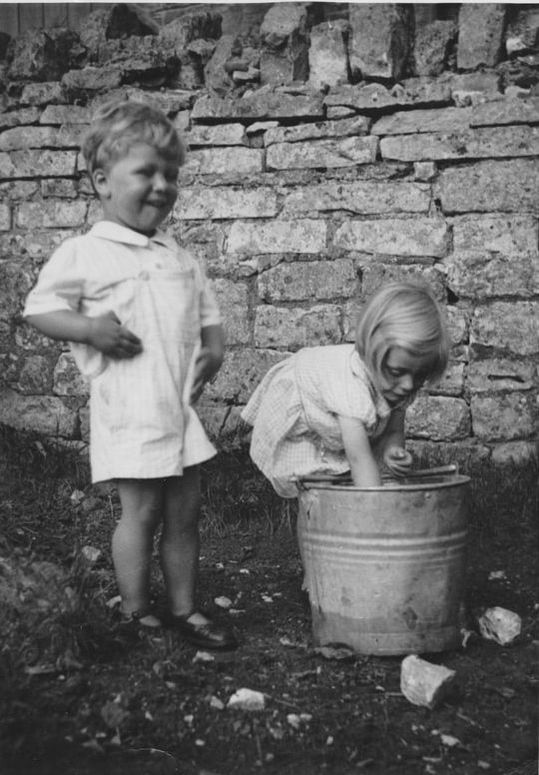

There are a few pictures of the evacuee children, including Mary Cox, daughter of a conscientious objector, who was evacuated to the area to work in agriculture in 1942 (above left) and Erica Webb (above right) who were keeping spirits up by performing in Bingham Hall entertainment in about 1940.

By May 1944, most of the evacuee children had returned home or had left school altogether. The Infants Department rooms in the Methodist School were vacated and lent to the War Emergency Committee to store facilities in the event of another local air blitz.[16] The London teacher, Miss Smith, who had come to Box with the evacuated children, was transferred out of Box and

Mrs Dark, who had taught at Box School for twelve years left the village for South Wales.

By May 1944, most of the evacuee children had returned home or had left school altogether. The Infants Department rooms in the Methodist School were vacated and lent to the War Emergency Committee to store facilities in the event of another local air blitz.[16] The London teacher, Miss Smith, who had come to Box with the evacuated children, was transferred out of Box and

Mrs Dark, who had taught at Box School for twelve years left the village for South Wales.

References

[1] The Blitz Pictorial, West of England Newspapers Ltd, 1979

[2] Richard Tombs, The English and their History, 2014, Allen Lane, p.688

[3] Claire Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.73

[4] Parish Magazine, May 1944

[5] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 9 September 1939

[6] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 16 December 1939

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 6 January 1940

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 February 1940

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 February 1940

[10] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 3 February 1940

[11] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 2 March 1940

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 29 June 1940

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 November 1940 and 11 January 1941

[14] Parish Magazine, January 1944

[15] Parish Magazine, July 1944

[16] Parish Magazine, May 1944

[1] The Blitz Pictorial, West of England Newspapers Ltd, 1979

[2] Richard Tombs, The English and their History, 2014, Allen Lane, p.688

[3] Claire Higgens, Box Wiltshire: An Intimate History, 1985, Downland Press, p.73

[4] Parish Magazine, May 1944

[5] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 9 September 1939

[6] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 16 December 1939

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 6 January 1940

[8] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 February 1940

[9] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 17 February 1940

[10] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 3 February 1940

[11] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 2 March 1940

[12] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 29 June 1940

[13] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 23 November 1940 and 11 January 1941

[14] Parish Magazine, January 1944

[15] Parish Magazine, July 1944

[16] Parish Magazine, May 1944