|

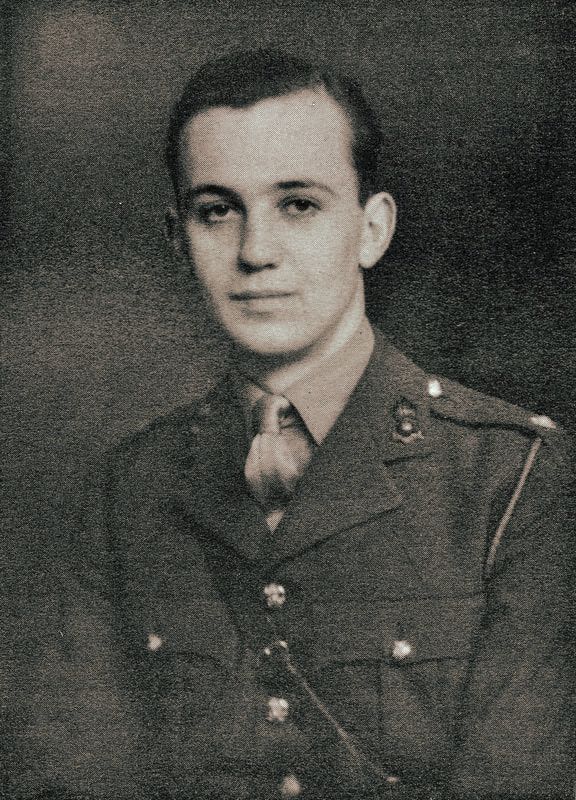

A Form of Consolation, 1942 - 1945: Epitaph to World War 2 Captain SJH Durnfold First published 1984 Illustrations Andrew Jackson John Durnfold lived at Greensleeves, the Market Place, Box, in 1984. He was born in 1920 and joined the Royal Artillery, Lanarkshire Yeomanry in 1939. He went to India and the Far East, and was captured at the Fall of Singapore in February 1942 where the Japanese killed 130,000 Commonwealth men and imprisoned 38,496 British troops. He was sent to Thailand later that year to build the Japanese strategic railway on the River Kwai from Thailand to the Burma. Casualties included 12,399 Allied soldiers and over 90,000 Asiatic labourers. He returned to England and was given a Regular Commission until 1953, when he was invalided from the army. Right: Captain John Durnford, December 1940 |

Author's Notes, February 1984

These poems were written on the River Kwai during the years 1942 - 1945 when I was an Allied Prisoner of War captured by the Japanese army. The beautiful, unexplored river rises in the mountainous North-West frontier and flows South-East for some 250 miles through the western province of Thailand. For the first 75 miles or so it descends gradually through jungle, rock and defile. In country where even Thai villagers were afraid to go because of wild-life that included panther, pythons, rattlesnakes and iguana. It was haunted, for them, by wood and water spirits completely virgin jungle, which only one previous expedition of surveyors had entered in 1929.

One of the largest convoys of troopships left the Clyde in March 1941. At Capetown, most of the ships were sent to Aden for the Middle East Campaigns. Ours reached Bombay in May. We trained with a brigade of Gurkhas and sailed from Bombay, round Ceylon and Dondra Head, across the Andaman Ocean, landing at Port Swettenham in North Malaya that August. The campaign that followed took us from Kedah, near the frontier with Thailand, the whole way down the peninsula from December 1941 to February 1942, when the island and city of Singapore capitulated. More than 20,000 of us were sent up to Thailand in October 1942 to begin building the strategic railway well known to film goers from seeing Sir Alec Guinness in "The Bridge on the River Kwai". The poems in this section are concerned with that experience, which almost defies description. No love letters were written from the Railway Camps. Letters from home did not arrive until 1943, and thereafter at six-monthly intervals. Barely more than 3,000 men survived.

Thanks to untiring efforts by Earl Mountbatten and 14th Army in Burma, the first convoy of survivors left Rangoon in September 1945, arriving at Southampton on October 8th. It was an interesting home-coming. Neither medical experts, families or friends knew what to make of those they had last seen four years before. We scarcely knew what to expect of docks, railways, cars, buses, radios, houses and telephones ourselves, having spent most of the interval working as native labourers in a tropical climate for a twelve hour day. Most terrible of ironies, wives had re-married and sweethearts had not waited. Regarding those they loved as not only Missing, but probably dead.

These poems were written on the River Kwai during the years 1942 - 1945 when I was an Allied Prisoner of War captured by the Japanese army. The beautiful, unexplored river rises in the mountainous North-West frontier and flows South-East for some 250 miles through the western province of Thailand. For the first 75 miles or so it descends gradually through jungle, rock and defile. In country where even Thai villagers were afraid to go because of wild-life that included panther, pythons, rattlesnakes and iguana. It was haunted, for them, by wood and water spirits completely virgin jungle, which only one previous expedition of surveyors had entered in 1929.

One of the largest convoys of troopships left the Clyde in March 1941. At Capetown, most of the ships were sent to Aden for the Middle East Campaigns. Ours reached Bombay in May. We trained with a brigade of Gurkhas and sailed from Bombay, round Ceylon and Dondra Head, across the Andaman Ocean, landing at Port Swettenham in North Malaya that August. The campaign that followed took us from Kedah, near the frontier with Thailand, the whole way down the peninsula from December 1941 to February 1942, when the island and city of Singapore capitulated. More than 20,000 of us were sent up to Thailand in October 1942 to begin building the strategic railway well known to film goers from seeing Sir Alec Guinness in "The Bridge on the River Kwai". The poems in this section are concerned with that experience, which almost defies description. No love letters were written from the Railway Camps. Letters from home did not arrive until 1943, and thereafter at six-monthly intervals. Barely more than 3,000 men survived.

Thanks to untiring efforts by Earl Mountbatten and 14th Army in Burma, the first convoy of survivors left Rangoon in September 1945, arriving at Southampton on October 8th. It was an interesting home-coming. Neither medical experts, families or friends knew what to make of those they had last seen four years before. We scarcely knew what to expect of docks, railways, cars, buses, radios, houses and telephones ourselves, having spent most of the interval working as native labourers in a tropical climate for a twelve hour day. Most terrible of ironies, wives had re-married and sweethearts had not waited. Regarding those they loved as not only Missing, but probably dead.

|

HUT BUILDING

Here, from where I'm sitting, the unfinished roof Hangs in its purlins like a spider's-net, Frail gossamer of finest warp and woof; Towards the apex points the ridge-pole, set Like a spine between bare ribs against the sky. We build, we scheme, we bury; who can tell Why this is so, and why we must, and why We've some connection with a star as well. Some double-meaning, some pretence to be More than mere poles lashed to a human-frame, And share a deeply found affinity With an immortal building just the same? And if the tie breaks, and the rafters go, Down to a little dust, we'll never know. Tamuang, December 17th 1944 |

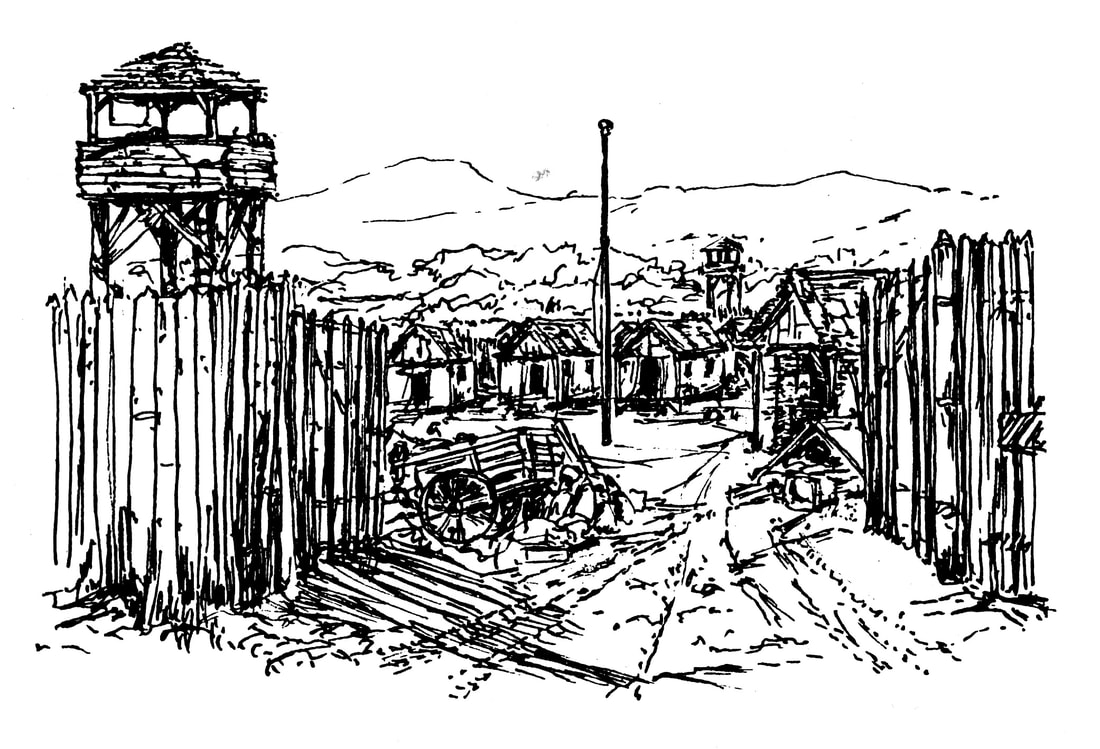

Written later, in 1944, recalls a feature of all camps. After the initial clearing of teak, and 50 foot clumps of bamboo, to form a site. Each hut was approximately 100 yards long, and could hold up to 200 men. The entire construction was of various lengths and diameters of bamboo. Cut and dragged from a clearing itself. Or brought downstream in the form of rafts. The roof was supported from a central bamboo ridge-pole, placed horizontally some 30 foot high. It was cambered steeply, and thatched with dried palm-leaves, in prepared sections. Called ATAP. These were brought up river by barges. They rotted in wet weather, drying to tinder in the sun. BUT were weather proof, unless one failed to over-lap the sections. A camp in the jungle resembled an orderly native village or Kampong. With its lines of long-huts. |

|

CASUALTY AT WORK

The burning head that pretty fingers bound To serve them with caressing lies still now, A dried husk in the sun; the matted brow That longed for love a greater peace has found. Clumsy hands bear him, only his friends Have any knowledge of the woes he bore Deep, festering in a mind that nothing mends, Of blows he took and feels not any more. When you get home, if any ask you there To spin them stories of their next-of-kin, Tell them I know the jungle-clearing where Sleeps, parchment black, her pale young lover's skin. Yes! tell the curious, eager for some tale, His heart did not grow faint, nor his eyes fail. Tonchan A Camp on the River Me-Nam-Kwa-Noi October 1943 |

Japanese Engineers supervised the jungle-clearing of the long trace, built through the forests. Which later, by mid-1943, held the railway embankment. Cuttings were blasted through rocky outposts. In every camp, spaced at an average of 10 km from each other, daily working parties would file out through rough-hewn tracks, about a mile to the site. Carrying with them, slung on bamboo poles, containers of rice to eat at mid-day. Food was a basic pound of boiled rice and vegetables daily. Dog fish were caught from the river and eaten. Men and sentries even grilled snakes over open fires, out at work. Excavating earth by hand, to build the embankment, involved a working day of 12 hours. From dawn to dusk. The work meant each man digging out a daily cubic metre. The man pictured in this poem has died of sun-stroke, starvation and exhaustion. The bodies were carried back to camp at night-fall on rough stretchers made of rice sacks, slung between carrying poles of bamboo. Needless to say there was no electricity in the camps. Such verse was written often at night by the light of rough oil lamps, made of small tins filled with cocoa nut oil. |

|

HOSPITAL VISITING HOURS

"Anything you want?" that's all he said, Standing embarrassed at the foot of my bed, Pity and awkwardness "Want!" I replied, "Only to live, mate!" "How's the world outside?" "What do you find to do?" I could have smiled, Lying there, watching the ceiling like a child, That finds words difficult. "Sleep", I said, "Sometimes, I dream". And turned away my head. "Goodbye for now" he whispered, "Goodbye!" I saw his face in the oil-lamp, a man's cry Rang down the hut. And, moments after, The trees outside were shrill with idiot laughter. Chungkai, September 1943 |

The Railway was finished by OCTOBER 15th, 1943. For several months beforehand, survivors like myself, from the working camps in the jungle, were moved down river by barges to large base camps like this one at CHUNGKAI, some 10 miles across country to the site of the now famous RIVER KWAI bridge. There was a total of some 4,500 Prisoners at CHUNGKAI, built where the river starts to flow through flat, sandy country in the SOUTH of KHANBURI province. It was on the site of an original FRENCH plantation, very rich in crop- and fruit-growing soil. Even the French manager's bungalow, hut remained in a clump of trees by the river. Do not imagine that the word "hospital" means anything like European hospitals. The camp was a large number of the usual long huts. Where devoted R.A.M.C. doctors worked on the many cases involved. These are all now chronicled in Dr. ROBERT HARDIE'S WAR DIARY, published in OCTOBER 1983, by The IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM. The majority were chronic cases of malaria, dysentery and heat exhaustion. BUT there were many more serious cases being treated in huts on the East side of the camp. Including amputations, often without the use of anaesthetics. It was, indeed, not an uncommon sight to see a portion of a human leg discarded in one of the waste-bins outside these huts. Those of us well enough to do so made frequent visits to friends in the hospital huts. One did one's best to console and comfort and cheer up the patients. BUT lack of experience made this difficult. And what does one say to men almost without hope of survival? The last line "The trees outside ... shrill with idiot laughter" refers not to human beings. BUT the endless screeching of Macaws and other night-birds, in the trees above the huts. |

|

IN THE MORNING

Look up, and raise your head, Beauty will not be comforted Alone, but from the branches cry For sympathy. And golden mouth to golden ear Call, and the troubled listeners hear A cry to liberate the soul, An oriole. Tobacco-smoke across the sun; The day begins, the tree-rats run Into the darkness of the tree, And comes to me, Like perfume on the morning air, The frangi-panis hidden there, That no cathedral ever caught Or a woman bought. And, in this still and pleasant shade, Our hovels and ourselves are made Palaces, by this ancient tree. And men set free. Tamuang Hospital, June 1944 |

In May 1944, the fitter survivors of what had been known as GROUP 4 of the jungle camps were moved out of CHUNGKAI, and reunited with their friends from upcountry. In another large river-side camp of some 3,000 men. One now had the time to reflect a little on the incredible beauty of the country itself. In greater peace of mind. TAMUANG became famous for two things, amongst others. Readers will recall the theme tune of Colonel BOGEY, the march used throughout the film, "BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI". The BRITISH ARMY have, of course, set some irreverent and bawdy words to this, Roll-call of the entire camp was held at dawn and sunset, on the large padang or open space by the huts. After numbering in tens we marched off past a saluting platform manned by a Japanese Officer. One evening to a small band, playing COLONEL BOGEY. The words were sung with some relish. The later famous TV QUIZ programme, "GIVE US A CLUE", probably owed its beginnings to evenings in the dark huts here. Where we acted out questions to each other in a game called more simply - "BOOK, PLAY, FILM". The easiest question to act was undoubtedly JAMES HILTON'S "LOST HORIZON". |

|

A FORM OF CONSOLATION

Lay your head against the post That all this shabby roof supports, May it take and quench all hurts On its cool skin, and all that most Hinders sleeping. Let it be More than a lover's brow to thee! Place your hand upon its side, Here there'll be no questioning, And, instead of a human bride, Querulous and chastening, A portion of more pity than A woman gave to any man. Kanchana Buri, August 1945 |

The EUROPEAN WAR ended in May 1945. In the PACIFIC, elements of the Japanese Co-Prosperity Sphere did not surrender until various dates after the ATOM BOMB fell on AUGUST 8th, 1945. The Camp at KHANBURI, where this poem was written, was capital town of the Province. With about 5500 Allied Officers interned in it. Early in August, rumours reached us that the Japanese Army Command were withdrawing forces to defend the islands of JAPAN itself. Our final letters, the last of only three mail deliveries in four and a half years, arrived from home. This poem was written to comfort a dear friend who received a letter from his wife, Informing him that, with no official information available as to whether he was alive or dead, she wrote regretfully to let him know she had re-married in 1943. Strong men such as this wept openly when they received such letters. There was little indeed that their friends could say to comfort them. Knowing also the tragic irony that they would be free soon, within a month. And at home in ENGLAND by OCTOBER 1945. |

|

VJ DAY KHANBURI

"Gentlemen!" he said in tears, "the war is over", Looking towards a yellow hurricane light, Held up by someone in the struggling crowd, I glimpsed your face, its usual smile Checked in bewilderment at so much joy, So you must once have looked, when, as a boy, They gave us gifts at Christmas - now, this Freedom, Silent, the men sat on in darkness, bowed and still, As though at prayers, or sleeping after death. Then slowly, one by one, as a great crowd Of ransomed spirits might attend their Lord, Began impulsive movements towards the door. Stars filled the jagged hills, the village slept. The shuffling feet paused. Then someone sang, Timid at first, their voices, gathered in strength, Sounding a great hymn from the ragged lines, While, all night long, drums beat in the darkened shrines. August 16th 1945 |

Japanese Armies in THAILAND were controlled from BANGKOK. Their supreme command was at SAIGON, in INDO CHINA, now VIETNAM. News of the Japanese surrender reached BANGKOK from SAIGON on or about AUGUST 12th 1945. A Japanese Major and others were sent to inform officers engaged in running our prisoner of war camps. The Captain commanding the camp at KHANBURI received the news and informed us on AUGUST 16th that WORLD WAR TWO was over. Messengers came from his office hut to every one of the prisoners' huts. Calling out the occupants to hear the news by the light of oil lamps. This was productive of indescribable scenes. The worn, tired faces reflected something akin to shock and disbelief. There were no demonstrations. Many sat in silence, some in tears, thanking GOD it was finished. BUT that night the entire camp gathered in the darkness in a long, random line. By the boundary fence that surmounted a deeply trenched moat. We sang endlessly, until after midnight. Forgotten and forbidden songs. Such as "GOD SAVE THE KING", "WALTZING MATILDA", The DUTCH National ANTHEM. And "THE STAR-SPANGLED BANNER". |

|

REPATRIATION, OCTOBER 1945

Autumn recalls to me The river-smoke hiding the feet of the mountains, The casuarina-trees, stiffening in the sky, The white Mongolian horses crossing the aerodrome, The saffron priests, alone in their meditations. England recalls to me The slow flotillas of bullock-carts travelling home, A querulous train, complaining on distant lines, A solitary bell that tolls in the shuttered village, The white birds flying away with us into the sun. |

A EUPHEMISM for Home-coming! The first two troopships arrived in LIVERPOOL and SOUTHAMPTON on OCTOBER 8th, 1945. Despite three whole years of tragedy, hardship, starvation and humiliation on The RIVER KWAI, it became possible, one evening at home, in meditation, to remember the natural beauties of the River itself. And the countryside. A line of casuarina-trees, like a file of cypresses, stood beyond the open space that lay between the last camp and the village of KHANBURI. The occasional BUDDHIST priest wore, always, the saffron-yellow robe of his order. And quietly flying flocks of white herons and osprey returned across the river at night. To their rest. As we were soon to do ourselves. |

Stanley John Harper Durnford remembered the horrors of his war for decades after the events he described so eloquently here.

He died in Bath in 1995.

He died in Bath in 1995.