Entertainment Alan Payne July 2022

Have you ever thought, “Not much on television tonight”? There was a lot less to be enjoyed every night in the 1920s and 30s but this was the age of the emergence of entertainment. One consequence of deep social change in the twentieth century was the increase of leisure, including holidays and non-working pleasure pursuits. In the 1920s entertainment developed with new technologies and ideas: wireless, cinema, sports and jazz, all of which circulated not through individual performances but as mass culture. People could see happenings in London and around the world and wanted to emulate them. It led to changes in family behaviour such as gatherings around the phonograph or radio to hear the news directly rather than relayed through the church.

Please be aware that this article includes contemporary language and descriptions

that are now considered insensitive towards people of other cultures.

that are now considered insensitive towards people of other cultures.

Shows during Great War and After

Theatres and the cinema stayed open in World War I, often bringing people news of the Western Front such as Battle of the Somme which is estimated to have had an audience of 20 million. An Entertainment Tax was introduced in 1916 which slowed numbers attending and stayed in place in the inter-war period. War plays continued after the armistice, the most famous of which was Journey’s End produced in 1928 about First World War trenches and starring Laurence Olivier.

Theatres and the cinema stayed open in World War I, often bringing people news of the Western Front such as Battle of the Somme which is estimated to have had an audience of 20 million. An Entertainment Tax was introduced in 1916 which slowed numbers attending and stayed in place in the inter-war period. War plays continued after the armistice, the most famous of which was Journey’s End produced in 1928 about First World War trenches and starring Laurence Olivier.

Of course, Box had no cinema. Instead, magic lantern shows were put on in the Bingham Hall. Some were rather improvised events such as the interesting pictures of Japan put on by Rev LC Cornwall of Chippenham which were made possible by Gilbert Sawyer who used his own lantern.[1] Many were of a rather sombre, educational nature. We get an idea of these from a 1917 children’s show with the starting and flight of aeroplanes, the launching of ships and the visit of the King to India.[2]

The atmosphere scarcely lifted after the war and in January 1924 entertainment included Two Palestine Days with tableaux and scenes illustrating life in the Holy Land as it was lived in Bible days.[3] As well as models and exhibits, the recently-opened Bingham Hall (1905) put on a show of life in the east using a limelight light (magic lantern show with brighter light often used where no electricity existed). The residents of Box appear to have recognised that they needed to upgrade social activities in the village by 1925 when postmistress Hester Fudge organised a Recreation Club.[4] There was a full programme of events in the Bingham Hall, including sketches by the Box Girl Guides, folk dancing by Box School children and humorous songs by Rev George Foster, Miss Hayward and Miss Cottell. It doesn't sound very modern but the club limped on until the Second World War.[5] It was only at the end of the inter-war period that commercial cinema came within easy reach of the village with the Regal Cinema which started in Corsham in about 1937 and the magnificent art deco Forum Cinema was opened in Bath in 1934, one of the last Super Cinemas to be built in England.

The atmosphere scarcely lifted after the war and in January 1924 entertainment included Two Palestine Days with tableaux and scenes illustrating life in the Holy Land as it was lived in Bible days.[3] As well as models and exhibits, the recently-opened Bingham Hall (1905) put on a show of life in the east using a limelight light (magic lantern show with brighter light often used where no electricity existed). The residents of Box appear to have recognised that they needed to upgrade social activities in the village by 1925 when postmistress Hester Fudge organised a Recreation Club.[4] There was a full programme of events in the Bingham Hall, including sketches by the Box Girl Guides, folk dancing by Box School children and humorous songs by Rev George Foster, Miss Hayward and Miss Cottell. It doesn't sound very modern but the club limped on until the Second World War.[5] It was only at the end of the inter-war period that commercial cinema came within easy reach of the village with the Regal Cinema which started in Corsham in about 1937 and the magnificent art deco Forum Cinema was opened in Bath in 1934, one of the last Super Cinemas to be built in England.

Performances in Box

Rev George Foster and his wife Kate came to Box in 1924 and formed a group amongst the congregation called The Player’s Guild to present amateur entertainment in the Bingham Hall. Some productions had large Biblical themes whilst others were song and dance routines, often fundraisers for church needs, such as church heating or organ restoration funds.

Rev George Foster and his wife Kate came to Box in 1924 and formed a group amongst the congregation called The Player’s Guild to present amateur entertainment in the Bingham Hall. Some productions had large Biblical themes whilst others were song and dance routines, often fundraisers for church needs, such as church heating or organ restoration funds.

We get an interesting picture of the vicar from reports of a garden party held at Hazelbury Manor in August 1927 despite continuous rain and virtually no audience.[6] Nonetheless, George continued with his performance as Foster Feast of Fun with his wife and daughter. George’s monologue included The Irish Orchestra and Three Nice Girls whilst his songs comprised Drink to me Only with Thine Eyes and The Mountains of Mourne. His daughter Betty put on a pretty golliwog dance, followed by sketches from the Box Blackbirds until George recommenced his monologues and impersonations.

The larger events were intended to make bible stories more accessible. We get some idea of the type of religious performances from reviews of the time. The Only Son Passion Play in Easter 1925 was written by Kate Foster, whose depiction of the Madonna was described as devotionally splendid.[7] A Second Pageant in April 1927 was based on the story of Joseph of Arimathea and St Augustine and was seen by 1,000 people in Box over two days.[8] In 1932 the Easter performance was Behold the Man written by Kate Foster. “Behold the Man” (Ecce Homine), were the words used by Pontius Pilate to show off the captured Christ to the crowd before the crucifixion. The play performed throughout the Holy Week at the Bingham Hall, admission free (although a collection tin was circulated), and different local clergymen gave introductory addresses before each performance, including the Bishop of Bristol who spoke at the Maundy Thursday performance.[9]

The main secular group was the Box Blackbirds putting on sketches by local residents held together by a professional comedian, sometimes by Box’s professional actor, Roddy Hughes, who had performed in shows like Rose Marie.[10] Sometimes performers were blacked up (white faces blackened) with songs including Swing low, Sweet Chariot, De Ol’ Banjo and Marching Through Georgia. It was the same sort of cultural insensitivity seen in 1927 by Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer and in the 1960s and 70s by The Black and White Minstrel Show. The shows were considered suitable to go on tour in 1927 to Poor Law houses at Rowden Hill, Chippenham Primitive Methodist Church in aid of Girl Guides and Winsley Sanatorium.[11]

The main secular group was the Box Blackbirds putting on sketches by local residents held together by a professional comedian, sometimes by Box’s professional actor, Roddy Hughes, who had performed in shows like Rose Marie.[10] Sometimes performers were blacked up (white faces blackened) with songs including Swing low, Sweet Chariot, De Ol’ Banjo and Marching Through Georgia. It was the same sort of cultural insensitivity seen in 1927 by Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer and in the 1960s and 70s by The Black and White Minstrel Show. The shows were considered suitable to go on tour in 1927 to Poor Law houses at Rowden Hill, Chippenham Primitive Methodist Church in aid of Girl Guides and Winsley Sanatorium.[11]

We can see how the types of entertainment in Box and how they altered in the mid-1920s from the list below:

|

Theatrical entertainment in the inter-war period

1925 A Revue 1925 July History Pageant at Hazelbury Manor 1925 April The Only Son Passion Play 1925 Nativity Play The Stranger 1925 October Mrs Gorringe’s Necklace. a comedy 1926 March Some Rubbish – a revue 1926 April More Rubbish, including References, a skit on the modern servant problem.[12] 1926 December The Stranger Nativity (again) and Mystery Play written by Kate Still More Rubbish. 1927 April Second Pageant based on story of Joseph of Arimathea 1927 Autumn Box Blackbirds tour 1929 March Easter Passion play cancelled because of vicar’s illness 1930 Dolly Reforming Herself comedic farce by Henry Arthur Jones 1930 November Church Army Pageant 1931 Easter The Way of Compassion 1932 Easter Behold the Man written by Kate Foster 1933 Easter The Shadow of the Cross 1933 December St Brigit of the Mantle and Outcasts.[13] |

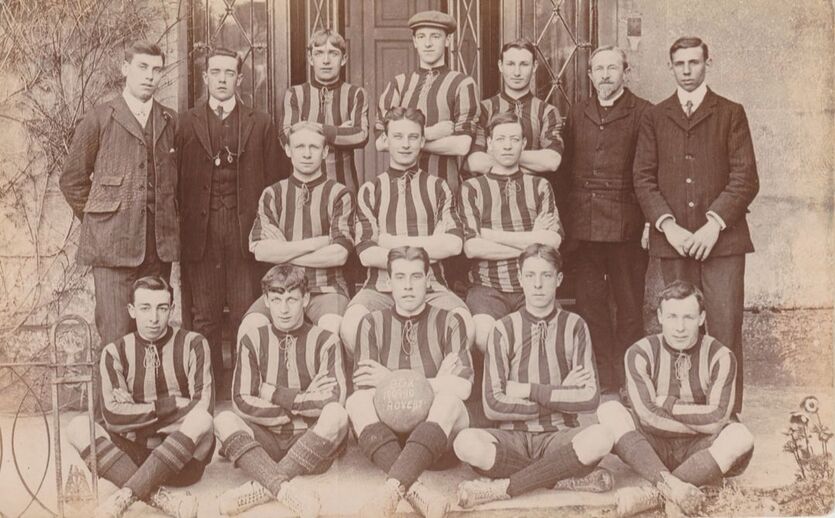

Purely secular entertainment was provided by other groups, such as a troupe of villagers calling themselves The Box Bricks (seen in headline photograph). Like the Blackbirds they also blackened up to put on shows. They catered for a general audience and put on a dance called Flannel Dance in 1930.[14] The evening was a more informal, casually-dressed event rather than the immaculate formality of dinner-jackets, which was the norm for middle-class villagers. It was a low-cost event with Mrs Davis of Chapel Lane requesting gifts of bread, butter lemonade, cakes, and milk for the catering. The Box Bricks appear to have been rather short-lived, as was the theatrical life of the Box Ladies Choir's production of Orpheus with his Lute.[15]

Leisure Clubs

In a world before radio, television and the internet, specialised clubs provided one of the main sources of interest and activity. A huge range existed for leisure, education and mutual support. For war ravaged families there were the Mothers’ Union, the British Legion and the Victorian Friendly Societies of the Royal Anti-Diluvian Order of Buffaloes and the Loyal Northey Lodge of Oddfellows and the Foresters. For young people there were the Scouts, the Girl Guides, the Ambulance Brigade and the Empire Builder’s Club (which offered billiards, whist and ping-pong). Other clubs were charity groups, such as the Box Clothing Club, the Kingsdown Coal Club and food & clothing providers.

Amateur sports clubs thrived in Box as a continuation of late Victorian enthusiasm: the Box Cricket Club and football clubs at Box, Box Hill and Kingsdown. They provided recreational time for quarrymen and working-class labourers who had continued their sport in the forces during World War I to pass leisure time and for exercise.

In a world before radio, television and the internet, specialised clubs provided one of the main sources of interest and activity. A huge range existed for leisure, education and mutual support. For war ravaged families there were the Mothers’ Union, the British Legion and the Victorian Friendly Societies of the Royal Anti-Diluvian Order of Buffaloes and the Loyal Northey Lodge of Oddfellows and the Foresters. For young people there were the Scouts, the Girl Guides, the Ambulance Brigade and the Empire Builder’s Club (which offered billiards, whist and ping-pong). Other clubs were charity groups, such as the Box Clothing Club, the Kingsdown Coal Club and food & clothing providers.

Amateur sports clubs thrived in Box as a continuation of late Victorian enthusiasm: the Box Cricket Club and football clubs at Box, Box Hill and Kingsdown. They provided recreational time for quarrymen and working-class labourers who had continued their sport in the forces during World War I to pass leisure time and for exercise.

References

[1] Parish Magazine, February 1926

[2] Parish Magazine, February 1917

[3] Parish Magazine, January 1924

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 7 February 1925

[5] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 20 August 1927

[7] Western Daily Press, 13 April 1925

[8] Parish Magazine, May 1927

[9] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 March 1932

[10] The Wiltshire Times. 23 July 1927

[11] The Wiltshire Times, 27 August 1927, North Wilts Herald, 28 October 1927 and Western Daily Press, 11 October 1927

[12] Wiltshire Tines and Trowbridge Advertiser, 10 April 1926

[13] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 July 1930

[15] Wiltshire Tines and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 September 1925

[1] Parish Magazine, February 1926

[2] Parish Magazine, February 1917

[3] Parish Magazine, January 1924

[4] The Bath Chronicle, 7 February 1925

[5] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 31 December 1938

[6] Bath Chronicle and Herald, 20 August 1927

[7] Western Daily Press, 13 April 1925

[8] Parish Magazine, May 1927

[9] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 March 1932

[10] The Wiltshire Times. 23 July 1927

[11] The Wiltshire Times, 27 August 1927, North Wilts Herald, 28 October 1927 and Western Daily Press, 11 October 1927

[12] Wiltshire Tines and Trowbridge Advertiser, 10 April 1926

[13] Parish Magazine, March 1934

[14] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 July 1930

[15] Wiltshire Tines and Trowbridge Advertiser, 19 September 1925