|

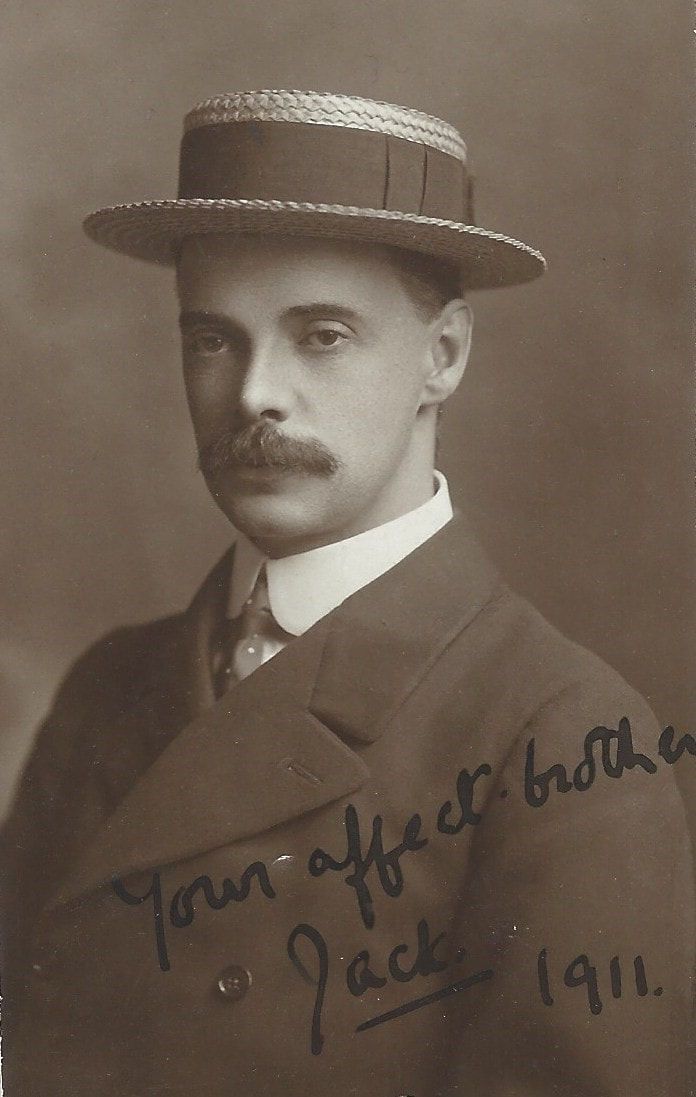

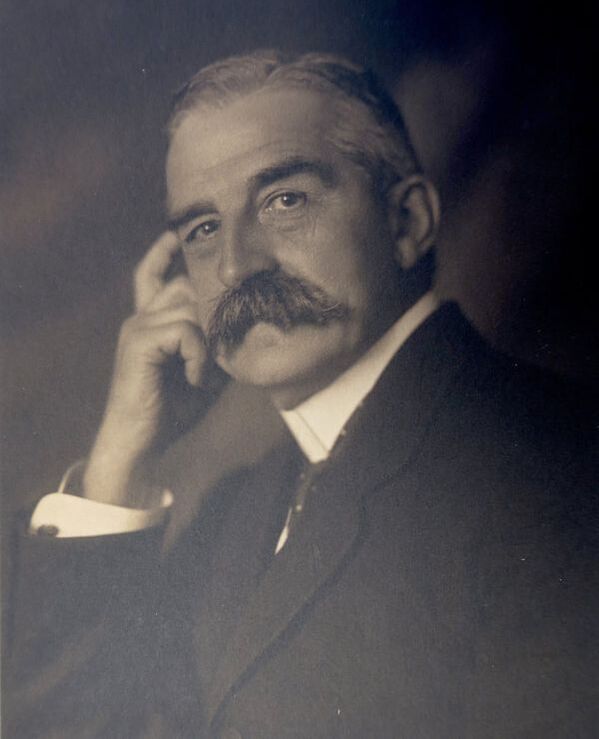

Your Affectionate Brother Jack Walters Angela Walters All photographs courtesy Walters family May 2023 Angela Walters has been researching her own and her husband’s family history for decades, going through box after box, file after file and corresponding with family all over the world to recover photos and manuscripts. Angela is the mother of renowned World War II author and historian Guy Walters. Her other son is Dominic Walters, Assistant Picture Editor at The Daily Telegraph. She obviously has the expertise to write this article.[1] Dr John Basil Walters worked at Kingsdown Mental Asylum for only a short time in the late Victorian period. He left for his own advancement at a time when the Box House was expanding under Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan. The experience of running a mental asylum clearly took a great toll on the staff and the story of Jack's work and personal character reflects the issues in caring for those in greater need than ourselves. Right: Dr John Basil Walters a few years before his death in 1918 |

Dr John (Jack) Basil Walters was born at Winchester on 15 April 1873 and died at Battle, Sussex, on 4 August 1918. He was the youngest child and seventh son of the Reverend Alfred Vaughan Walters of Wyke, Winchester, and his wife Frances Amelia Dodsley-Flamstead. When his father, a cranky, domineering clergyman, died in 1891, his mother Frances left Winchester for London, living a nomadic life staying with sons and daughters in the capital or in the West Country. Jack left the family home and became a stockbroker’s clerk aged seventeen. He stayed with his brother Lieutenant-Colonel George Wolferstan Walters, a member of the London Stock Exchange specialising in gold shares, who despite his age later had a distinguished Great War service training many field companies.

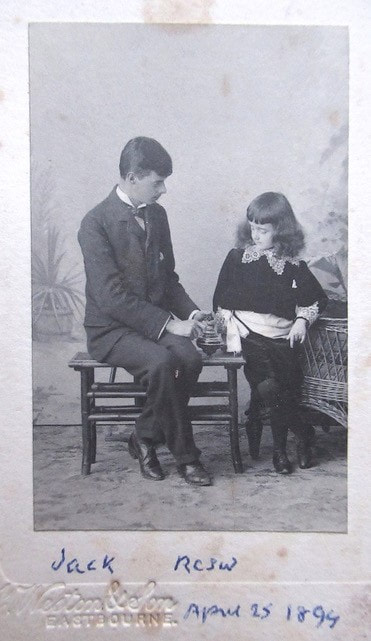

Above Left: Jack as a child in 1881 and Right: Talking to his nephew Rupert Cavendish (Caven) Skyring Walters, the father of Angela’s husband Martin in 1894

|

Medical Training

However, stockbroking was not a career Jack wished to pursue and in late 1892 he was registered at Guy’s Hospital, London, to commence his medical studies. A new medical college had recently been opened at Guy’s Hospital and Jack lived with his mother at Anerley, South London, in 1891, close to his brother George and his family at Penge. After passing the examinations, Jack took breaks from his studies to travel. In January 1895 he went to New York, returning three months later. When he passed exams in Anatomy and Physiology, and was finally able to describe himself as “medical”, he went to Paris in March 1896, back to the USA to visit relatives in Florida, and then to see Niagara Falls and other sites in November 1897. This period seems to have been an enjoyable and relaxing time for Jack. One of his nieces, Hilda Campbell (nee Walters), wrote in her later years of Jack’s visits to her family when they were living in Cornwall in the 1890s, first at Hornacott Manor, then Bamham House, and finally Crinnis Manor. She said that Jack was devoted to his nieces and nephews, and they loved him. Hilda wrote, he was so understanding and wise, but also youthful. She told of his taking them by train for tea in Fowey where they had splendid feasts, and of his telling them stories. Uncle Jack, who knew about everything and was interested in explaining it to us, told us of a heavy chain that went all the way across Fowey Harbour. It was put there originally to keep out the French, and it was there still.[2] |

Working Life

On 29 July 1899, Jack was registered as Assistant Medical Officer at Kingsdown House. It had been taken over by Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan who developed it into a hospital for mental and nervous diseases with around 40 residents. It was probably his first position and he was unanimously elected as a member of the British Medical Association in October 1899.

On 29 July 1899, Jack was registered as Assistant Medical Officer at Kingsdown House. It had been taken over by Dr Henry Crawford MacBryan who developed it into a hospital for mental and nervous diseases with around 40 residents. It was probably his first position and he was unanimously elected as a member of the British Medical Association in October 1899.

Kingsdown Asylum in 1903 showing above Left: the tennis court lawn and Right:The Blocks

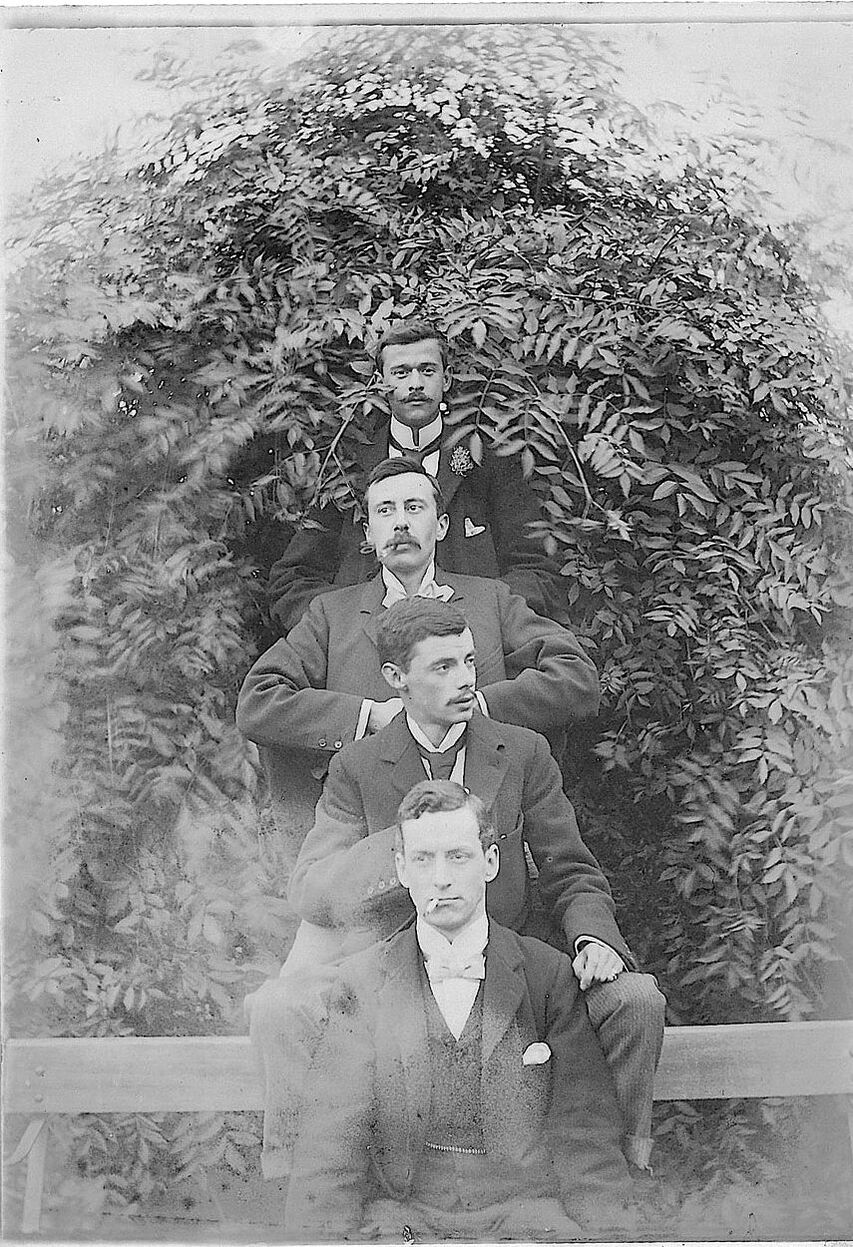

His time in Box was short, only a few months, and by 1901 Jack had taken a nearby position as Physician and Surgeon, Assistant Medical Officer at Bailbrook Asylum, Bath, still retaining a friendship with Box. Bailbrook was a similar set up to the Box asylum with the resident owner and his family and 33 resident patients. He had a substantial social circle with visits to Dr Alfred John Hull and his wife Eleanor Gainsford, a music hall star, and Margaret Clutterbuck at Bathford House. His friendship with

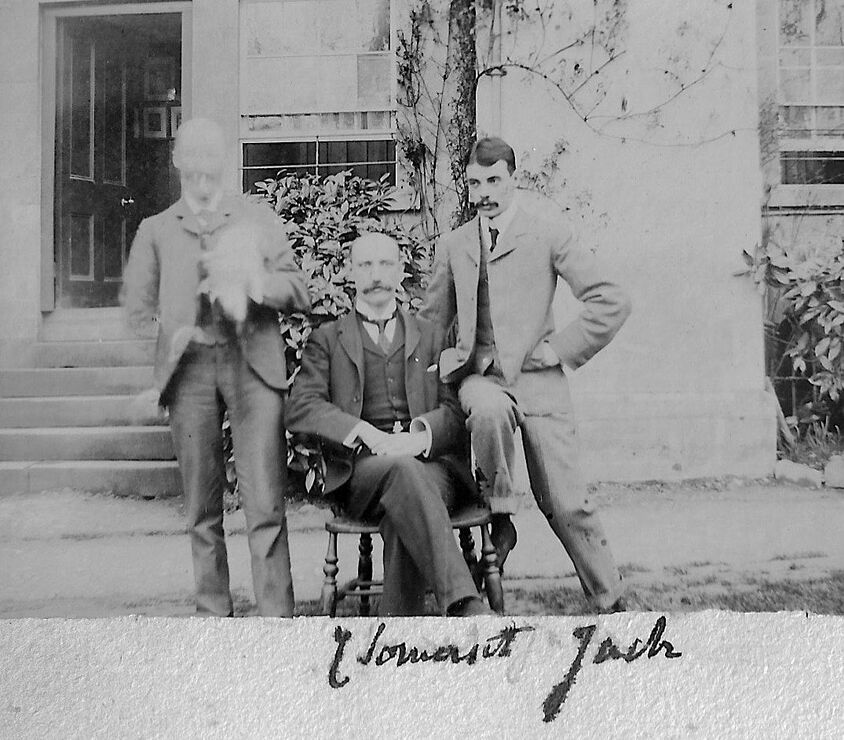

Dick Somerset (possibly Charles Somerset, a fellow boarder at Bailbrook who was described as Companion to gentleman in the census of 1901) resulted in several photographs of Dick. Jack had remained on good terms with Henry MacBryan and, as a keen stamp collector, the Macs gave him a huge, heavy stamp stock book in 1903.

Dick Somerset (possibly Charles Somerset, a fellow boarder at Bailbrook who was described as Companion to gentleman in the census of 1901) resulted in several photographs of Dick. Jack had remained on good terms with Henry MacBryan and, as a keen stamp collector, the Macs gave him a huge, heavy stamp stock book in 1903.

Jack had several hobbies especially family research with pages and pages of notes being worked in the years around 1903 with his brothers. He was intrigued with researching the family tree, compiling one called Royal Pedigree of the Walters’ Family showing and including descent from Alfred the Great. Jack also worked on the Victorian obsession for a family coat-of-arms and a family crest. Bookplates, silver signet rings, silver cigarette boxes, silver flatware, gold and silver cuff links and similar items were engraved with mottos. It was not only Jack’s passion as his brother Colonel Herbert Flamstead Walters compiled their research into a book in 1907, The Family of Walters of Dorset and Hants. Another was the major research by Frederick Walters of Vodin, Pyrford, Surrey.

|

In 1911 Jack was staying with his widowed brother William Charles Flamstead (Charlie) Walters and his son Caven at Limen, Gerrards Cross, an Arts & Crafts house suitable for the family of a Classics university professor. Jack rose quickly in status and in 1905 was the Resident Medical Officer in a prestigious asylum at Ticehurst, East Sussex, run by the Newington family. The asylum was set in huge, landscaped gardens and catered for very wealthy patients with psychiatric problems. Based on his experiences there, Jack rented rooms for a private practice at 51 Devonshire Place and 9 Park Crescent, Portland Place, Westminster, from 1906 to 1914.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, he moved to Buckinghamshire and continued his private practice at Dunholme, Gerrards Cross. This was the home and business premises of Louis Albert Dunn, the eminent senior surgeon at Guy’s Hospital between 1906 and 1918. Louis was 15 years older than Jack and the two had been friends for some time, so much so that a close relative had written in 1912: Hasn’t Uncle Jack got over the doctor yet? Right: Dr Louis Albert Dunn (1858-1918) courtesy the King’s Archive, King’s College London |

Jack remained in touch with his family and when his niece Hilda Walters returned from the USA to nurse during 1916-17 in the Great War, Jack went to the railway station with Louis Dunn to welcome her when she arrived at Gerrards Cross. Hilda wrote:

I was so happy to see Uncle Jack that I threw my arms around him, which made Mr. Dunn smile, as one did not give way to one’s affections in railway stations.[3] It is interesting to contrast family comments about Jack. Hilda described him as a kindly, attentive, interesting and humorous man but his oldest brother Alfred (Bo) Hugh Walters, a member of the London Stock Exchange, referred to him in derogatory terms, when describing his sitting on a swing as the manliest thing Jack ever did.

Hilda, however, remained devoted to the memory of her Uncle Jack all her long life. Her granddaughter speculates that his death was the most devasting of all the tragedies she experienced.

I was so happy to see Uncle Jack that I threw my arms around him, which made Mr. Dunn smile, as one did not give way to one’s affections in railway stations.[3] It is interesting to contrast family comments about Jack. Hilda described him as a kindly, attentive, interesting and humorous man but his oldest brother Alfred (Bo) Hugh Walters, a member of the London Stock Exchange, referred to him in derogatory terms, when describing his sitting on a swing as the manliest thing Jack ever did.

Hilda, however, remained devoted to the memory of her Uncle Jack all her long life. Her granddaughter speculates that his death was the most devasting of all the tragedies she experienced.

The Dunn family were very wealthy and Dunholme was an extensive property with 3 reception rooms, 8 bedrooms, billiard room and offices, all set in an acre of ground in North Park, one of the best residential areas of Gerrards Cross. Louis Dunn never married and died on 7 June 1918 of renal failure. Jack was made homeless when the property was put up for sale in July 1918, so he moved down to Ashbrook Hall, Hollington, St Leonards-on-Sea. This was the small Licensed Ladies Mental Asylum (and personal home) of his long-term friend Charles Edward Henry (Dick) Somerset, whom he had known since his time at Bailbrook House. Dick Somerset married and fathered five children but questions remained about the nature of Jack’s friendship with him.

Jack Walters’ Death, 5 August 1918

Jack died two months after Louis Dunn, believed to be heart-broken after the loss of so many family and friends due to inevitable old age, certainly disease that as yet had no cures (TB was rampant and Charlie’s wife Ethel died too young of that) and the dead of the Great War. Jack was aged only 45. He had few effects and left his estate of £1,596.11s (today worth £130,000) to his sister Florence Margaret (Moggie), wife of Thomas Bowyer-Bower. An inquest was held and Jack’s death certificate recorded Syncope (fainting fit) due to chronic gastric catarrh. Natural causes.

This was far from the complete story, however, as recalled in a long, “heroic” letter of 26 August 1918 written by Moggie to her family, extracts of which show her deep protective sibling love for her brother and revised the family opinion that Jack and Dick Somerset had an intimate relationship. It is still regarded as a family treasure:

Jack died two months after Louis Dunn, believed to be heart-broken after the loss of so many family and friends due to inevitable old age, certainly disease that as yet had no cures (TB was rampant and Charlie’s wife Ethel died too young of that) and the dead of the Great War. Jack was aged only 45. He had few effects and left his estate of £1,596.11s (today worth £130,000) to his sister Florence Margaret (Moggie), wife of Thomas Bowyer-Bower. An inquest was held and Jack’s death certificate recorded Syncope (fainting fit) due to chronic gastric catarrh. Natural causes.

This was far from the complete story, however, as recalled in a long, “heroic” letter of 26 August 1918 written by Moggie to her family, extracts of which show her deep protective sibling love for her brother and revised the family opinion that Jack and Dick Somerset had an intimate relationship. It is still regarded as a family treasure:

|

“Dick Somerset wired for me and Jack found dead 5 August. It was Bank Holiday and no trains, hardly any cabs and no porters. The police came and summoned me to Jack’s inquest. They gave me to understand there was some terrible mystery. Finally arrived at Hastings and found Bo to meet us and Dick Somerset told me privately that there was no doubt Jack had taken his own life and had been mad for years. Of course, I would not admit this and got very upset. I could see (the inquest) had only one idea and only looked for one thing – poison. All they went on was a white patch found in his stomach, apparently burnt from corrosive.

A second inquest was called in a fortnight. I worked and worked and wired and wrote to every doctor Jack ever knew to prove his state of health. Dick Somerset wrote around and told everyone Jack was deranged and said he knew positively Jack had taken poison. Dr Huckle who was at Guy’s with Jack was ordered to make an examination and analysis. It was proved by him without a shadow of doubt Jack died of natural causes owing to his weak state. He only weighed 8 stone (under) and was 5 feet 11½ inches high. Jack’s last wishes about cremation not carried out as coroner would not permit it. But I took him to Rickmansworth and he is in a grave he bought next to Mother’s. After it was all over, I felt completely done with the anxiety, work, tears and fears. Bo was so strange throughout. The loss of Jack was bad enough, God only knows. And the stigma left by Dick Somerset. Never liked the fellow and never shall.[4] Jack lay on his left side as if sleeping and holding a hot water bottle to his side. The bed was neat and tidy. I had a letter from him dated 4th, the day before. All about where he was taking a house etc but he complained terribly about insomnia. Yet Dick could not see all this and only said his mind was deranged! Yet he had certified a patient on 25 July!! I don’t know what he says now at the verdict. He wrote to me and never mentioned it!! Never owned he was in the wrong! I will destroy his letters. Jack left me sole executor and all his worldly possessions but I do so wish he was here himself instead. I feel so sure he would never have died if I had only known he was really ill and gone to him. He kept quiet and was so uncomplaining but I know he expected it. Everything left neatly and ready and a notice to a solicitor should he die on account of difficult times to be buried where he died. It was dated only a few weeks previous.” |

|

Conclusion We will never know the truth about Jack’s death but this hardly seems relevant. We have moved beyond the time when sexuality and suicide were social stigmas. We now recognise the truth that those who give much care and consideration to others are often those most in need of our help and compassion. Jack’s life shows the lasting and widespread value of the kindness he showed to people, especially children, and the warmth it spread over their lives. In these matters, his example is still practised by his family. Perhaps that is the real moral of Dr Jack Basil Walter’s life. As Angela herself said: “Finally Uncle Jack will no longer be a footnote in history as the last and eleventh child of his parents. Jack’s last years were filled with endless tragic loss of family and friends — so very sad to write about. Perhaps Jack lost the will to live. Jack’s is a brief story of a brief life though I am sure he made a huge difference to the many he helped with their mental problems: a life worthily lived however so short.” Right: Jack's final resting place at Rickmansworth |

References

[1] Guy Walters - Wikipedia

[2] Hilda Campbell (nee Walters), Old Women Remember: Notes, Quotes & Anecdotes

[3] Hilda Campbell (nee Walters), Old Women Remember: Notes, Quotes & Anecdotes

[4] The letter then talks about wartime matters including how hard Moggie’s husband had been affected by the death of their son, RFC Captain Ethelred Wolferstan Bowyer-Bower, shot down in March 1917 and her own wartime experiences.

[1] Guy Walters - Wikipedia

[2] Hilda Campbell (nee Walters), Old Women Remember: Notes, Quotes & Anecdotes

[3] Hilda Campbell (nee Walters), Old Women Remember: Notes, Quotes & Anecdotes

[4] The letter then talks about wartime matters including how hard Moggie’s husband had been affected by the death of their son, RFC Captain Ethelred Wolferstan Bowyer-Bower, shot down in March 1917 and her own wartime experiences.