|

Where was Ditteridge? Text and photos Jonathan Parkhouse November 2022 The boundary between the parishes of Box and Ditteridge was complex; when the Tithe plans for Box and Ditteridge were drawn in 1838 there were no less than twenty-seven separate areas making up Ditteridge parish. Most were north of the hamlet that we now know as Ditteridge, but there were pockets of land belonging to Ditteridge parish (some of minute extent) throughout the western part of Box parish. Emergence of the Parishes The spatial arrangement of the two parishes denotes a manorial and parochial history of some complexity, but not one which is readily comprehended. Parishes developed independently of manors and estates; the parish was a community as much as an area of land, which paid tithes and other obligations to support a priest who was responsible for the care of souls within his charge and would officiate at worship in a church building. Many church buildings, apart from the earlier minster foundations, originated as proprietary churches established by lay landowners on their estates or manors. We know that a manor, or at any rate a place, called Hazelbury existed in AD 1001, when a charter of an adjacent estate in Bradford hundred referred to þe kinges imare at Heselberi (the king's boundary at Hazelbury) and there was a church there in Domesday Book in AD 1086.[1] |

Ditteridge is first referred to in Domesday Book, whilst the earliest known references to Box are not until the twelfth century. Although Domesday Book contains four entries relating to Hazelbury (Haseberie) and one for Ditteridge (Digeric) it is not possible to assess with any certainty where the limits of the land-holdings lay or how those boundaries may have changed over time. At least one of the Domesday estates may have subsequently become, or been incorporated into, Box parish, but Box seems to have remained distinct from Hazelbury; the will of Sir John Bonham of Hazelbury of 1503 includes bequests to both Box Church, where Bonham wished to be buried, and Hazelbury Church.[2] Both churches are referred to as parish churches (parochiali) in Bonham’s will, but subsequently there is no further mention of Hazelbury as a discrete parish and the church may already have been in decay by the time of Bonham’s bequest.

Putting Ditteridge on the map

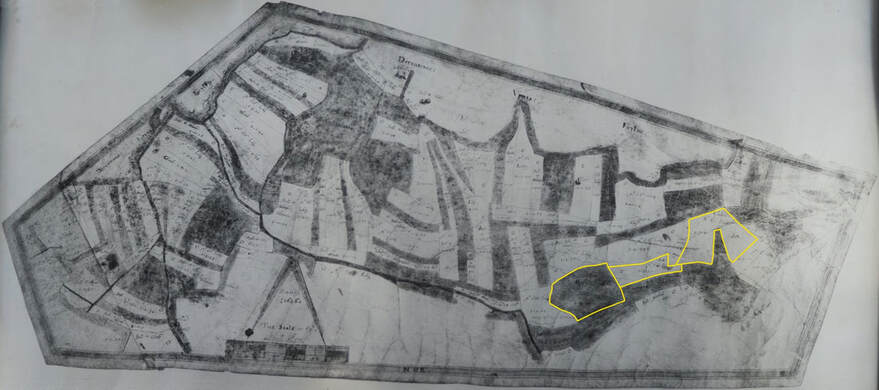

The earliest detailed maps of the area are those drawn up by Abraham Allen in 1626. The principal map, which has illustrated several articles on this website, was described as The Plot and Survaye of the Mannors: Hayselbury Box and Ditchredg. A revised map, similar but with some boundaries corrected, was drawn up by Francis Allen, a relative of Abraham, in 1630. These show the estate owned by the Speke family, which incorporated all of present-day Box parish, apart from Rudloe, and all of Ditteridge, and it is evident that the lands of Ditteridge parish were already closely entangled with those of Box.[3] The title indicates that, in the mind of the owner at least, there were still three distinct manors, although by this time the administrative distinctions, at least between Box and Hazelbury, were probably rather blurred. Abraham Allen’s 1626 map of the entire estate was accompanied by plans of the individual open fields, which show that they had already been subjected to episodes of piecemeal enclosure.[4]

By 1626 the areas of open field are far smaller than they would have been during the medieval period. Ditteridge Upper and Lower Fields clearly belonged to Ditteridge parish, whilst Box Field will have belonged to Box. Chapel Field, just south of Hazelbury manor, is likely to have belonged originally to Hazelbury, whilst the other areas of open field – Tile Pit Field (also called Tile Quarr Field) and Blacklie Field may have belonged to either Box or Hazelbury.

The earliest detailed maps of the area are those drawn up by Abraham Allen in 1626. The principal map, which has illustrated several articles on this website, was described as The Plot and Survaye of the Mannors: Hayselbury Box and Ditchredg. A revised map, similar but with some boundaries corrected, was drawn up by Francis Allen, a relative of Abraham, in 1630. These show the estate owned by the Speke family, which incorporated all of present-day Box parish, apart from Rudloe, and all of Ditteridge, and it is evident that the lands of Ditteridge parish were already closely entangled with those of Box.[3] The title indicates that, in the mind of the owner at least, there were still three distinct manors, although by this time the administrative distinctions, at least between Box and Hazelbury, were probably rather blurred. Abraham Allen’s 1626 map of the entire estate was accompanied by plans of the individual open fields, which show that they had already been subjected to episodes of piecemeal enclosure.[4]

By 1626 the areas of open field are far smaller than they would have been during the medieval period. Ditteridge Upper and Lower Fields clearly belonged to Ditteridge parish, whilst Box Field will have belonged to Box. Chapel Field, just south of Hazelbury manor, is likely to have belonged originally to Hazelbury, whilst the other areas of open field – Tile Pit Field (also called Tile Quarr Field) and Blacklie Field may have belonged to either Box or Hazelbury.

The map for Ditteridge Upper and Lower fields is shown here, and indicates clearly the individual land allocations within the open fields. These form an irregular mosaic of plots ranging in size from less than a quarter of an acre to around four acres.

Some amalgamations of adjacent strips are evident, and the relatively small number of tenants identified shows that the communal organisation of the open fields was now in the hands of a small number of individuals.[5] The map also labels three adjacent plots of land within the fields as belonging to Box.

Unfortunately, there are insufficient points on the 1626 map of Ditteridge open field which may be precisely correlated with identifiable points on the ground, so it has not proved possible to plot the outline of the open fields on to current mapping. Abraham Allen is likely to have compiled the open field map at the same time as he was surveying the rest of the estate.

It is reasonable to suppose that Allen was using a plane table and some form of measuring cord; the surveyors chain had only very recently been invented and the scale bars on the Allen maps are not calibrated in chains.[6] Whilst the Allens were competent surveyors for their day, they appear to have started the survey in the centre of the Speke estate and worked their way towards the edges; by the time they reached the periphery of the estate cumulative errors had crept in and georeferencing the edges of the maps is problematic; the problem is most acute to the north of Ditteridge church. What is evident, despite these problems, is that the shape of the Ditteridge open fields shown by Allen, and those areas indicated as being within Box parish,

do not entirely correspond with the situation shown on the Tithe plans, suggesting that changes to the parochial boundaries continued after the compilation of the Allen maps.

Some amalgamations of adjacent strips are evident, and the relatively small number of tenants identified shows that the communal organisation of the open fields was now in the hands of a small number of individuals.[5] The map also labels three adjacent plots of land within the fields as belonging to Box.

Unfortunately, there are insufficient points on the 1626 map of Ditteridge open field which may be precisely correlated with identifiable points on the ground, so it has not proved possible to plot the outline of the open fields on to current mapping. Abraham Allen is likely to have compiled the open field map at the same time as he was surveying the rest of the estate.

It is reasonable to suppose that Allen was using a plane table and some form of measuring cord; the surveyors chain had only very recently been invented and the scale bars on the Allen maps are not calibrated in chains.[6] Whilst the Allens were competent surveyors for their day, they appear to have started the survey in the centre of the Speke estate and worked their way towards the edges; by the time they reached the periphery of the estate cumulative errors had crept in and georeferencing the edges of the maps is problematic; the problem is most acute to the north of Ditteridge church. What is evident, despite these problems, is that the shape of the Ditteridge open fields shown by Allen, and those areas indicated as being within Box parish,

do not entirely correspond with the situation shown on the Tithe plans, suggesting that changes to the parochial boundaries continued after the compilation of the Allen maps.

A Complex Pattern

We do not know precisely when the open fields of Box were laid out, or the parishes established, but the period between the tenth and the twelfth centuries is most likely; certainly the southern boundary of Hazelbury had been established along the line of the former Roman Road from Bath eastward to Silchester by 1001. What happened over the succeeding centuries to create such a complex pattern which had resulted by the early seventeenth century, if not earlier, in the highly fragmented and dispersed distribution of land associated with Ditteridge?

Whilst parishes in southern England normally consisted of a single territorial entity, parishes with several detached portions were not especially unusual until local government administrators from the nineteenth century onwards began to ‘tidy up’ what could be complicated local arrangements. Parishes with multiple detached portions could arise in several ways.[7] Sometimes a non-parish church such as a chapel of ease could be promoted to parish status and a proportion of the tithes retained by the mother church. In other cases, two parishes might have intercommoning rights over woodland and waste, or a single settlement became divided into two parishes, each sharing a single field-system, and perhaps also sharing the tithes. In such cases lands and strips in the open fields which had originally belonged to a single mother church were gradually consolidated in piecemeal fashion into separate and distinct parochial units.[8] We cannot tell whether any of these models match the situation in Box and Ditteridge; the present parish encompasses a number of early land units for which we have little documentation, and we can only say that the first detailed maps of the early seventeenth century show the later part of a complex process of change in land ownership and parochial allegiance.

By the early modern period ecclesiastical parishes had taken on administrative roles as the influence of manorial courts diminished. At the start of the seventeenth century parishes gained the power to levy rates for poor relief. The functions of civil and ecclesiastical parishes diverged during the nineteenth century, with responsibility for poor law administration transferred from parish vestries to Boards of Guardians, whilst the growth of nonconformism brought the authority of the established Church of England in respect of civic affairs into question. The practicality of such a small and fragmented parish as Ditteridge diminished, and the civil parish was amalgamated with Box in 1884.

We do not know precisely when the open fields of Box were laid out, or the parishes established, but the period between the tenth and the twelfth centuries is most likely; certainly the southern boundary of Hazelbury had been established along the line of the former Roman Road from Bath eastward to Silchester by 1001. What happened over the succeeding centuries to create such a complex pattern which had resulted by the early seventeenth century, if not earlier, in the highly fragmented and dispersed distribution of land associated with Ditteridge?

Whilst parishes in southern England normally consisted of a single territorial entity, parishes with several detached portions were not especially unusual until local government administrators from the nineteenth century onwards began to ‘tidy up’ what could be complicated local arrangements. Parishes with multiple detached portions could arise in several ways.[7] Sometimes a non-parish church such as a chapel of ease could be promoted to parish status and a proportion of the tithes retained by the mother church. In other cases, two parishes might have intercommoning rights over woodland and waste, or a single settlement became divided into two parishes, each sharing a single field-system, and perhaps also sharing the tithes. In such cases lands and strips in the open fields which had originally belonged to a single mother church were gradually consolidated in piecemeal fashion into separate and distinct parochial units.[8] We cannot tell whether any of these models match the situation in Box and Ditteridge; the present parish encompasses a number of early land units for which we have little documentation, and we can only say that the first detailed maps of the early seventeenth century show the later part of a complex process of change in land ownership and parochial allegiance.

By the early modern period ecclesiastical parishes had taken on administrative roles as the influence of manorial courts diminished. At the start of the seventeenth century parishes gained the power to levy rates for poor relief. The functions of civil and ecclesiastical parishes diverged during the nineteenth century, with responsibility for poor law administration transferred from parish vestries to Boards of Guardians, whilst the growth of nonconformism brought the authority of the established Church of England in respect of civic affairs into question. The practicality of such a small and fragmented parish as Ditteridge diminished, and the civil parish was amalgamated with Box in 1884.

Marking the Boundaries

Apart from the maps, we have one other important source of evidence for the arrangement of the parishes before the nineteenth century. The boundaries of the parishes, here as elsewhere, were marked by boundary stones or ‘merestones’. In many parishes ‘beating the bounds’ took place at Rogationtide, which was the period between the fifth Sunday after Easter and Ascension Day. A procession led by the priest perambulated the parish boundaries, so that the parishioners would remember, in an age before maps, where the boundaries were. Often food and drink were partaken of during the day and the crops in the fields would be blessed. In some parishes youths in the procession would be given a not-so-gentle reminder at certain points along the boundary, such as twisting an ear or even a beating, to better fix their location in the memory. Parishioners might also leave marks along the route, some ephemeral, some more durable. Additional impetus for marking the boundaries was provided by the Highways Act of 1555 which gave the parish responsibility for road maintenance, and definition of the limits of a parish’s financial responsibility in this regard became important.

The merestones of Ditteridge thus provide a tangible reminder of parochial history. They consist of single stone orthostats

(square stone blocks) up to about 0.5m tall in local oolitic stone, inscribed B D or D B. In most instances a vertical line between the two letters is continued as a groove across the top of the stone; this was intended to mark the actual line of the boundary. There is no evidence for the date at which they were erected; the lettering seems to indicate a date between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries, but with only two letters used there is not much in the way of stylistic detail to analyse. Slight variations in the style may suggest that they were not necessarily erected in a single operation.

A previous article in Box People and Places states that twenty-five stones still remained in 2014.[9] The present author has only been able to locate eight, but others may await discovery.[10] Some of the surviving merestones are as follows:

Apart from the maps, we have one other important source of evidence for the arrangement of the parishes before the nineteenth century. The boundaries of the parishes, here as elsewhere, were marked by boundary stones or ‘merestones’. In many parishes ‘beating the bounds’ took place at Rogationtide, which was the period between the fifth Sunday after Easter and Ascension Day. A procession led by the priest perambulated the parish boundaries, so that the parishioners would remember, in an age before maps, where the boundaries were. Often food and drink were partaken of during the day and the crops in the fields would be blessed. In some parishes youths in the procession would be given a not-so-gentle reminder at certain points along the boundary, such as twisting an ear or even a beating, to better fix their location in the memory. Parishioners might also leave marks along the route, some ephemeral, some more durable. Additional impetus for marking the boundaries was provided by the Highways Act of 1555 which gave the parish responsibility for road maintenance, and definition of the limits of a parish’s financial responsibility in this regard became important.

The merestones of Ditteridge thus provide a tangible reminder of parochial history. They consist of single stone orthostats

(square stone blocks) up to about 0.5m tall in local oolitic stone, inscribed B D or D B. In most instances a vertical line between the two letters is continued as a groove across the top of the stone; this was intended to mark the actual line of the boundary. There is no evidence for the date at which they were erected; the lettering seems to indicate a date between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries, but with only two letters used there is not much in the way of stylistic detail to analyse. Slight variations in the style may suggest that they were not necessarily erected in a single operation.

A previous article in Box People and Places states that twenty-five stones still remained in 2014.[9] The present author has only been able to locate eight, but others may await discovery.[10] Some of the surviving merestones are as follows:

Three merestones in the centre of the present hamlet are intervisible: Above Left: Outside The Bungalow, Ditteridge, on road verge (ST 81767 69413) D|B,

(? displaced). Intervisible with middle and right.

Above Middle: Opposite previous merestone, on the east side of the junction of the lane to St Christopher's Church and Road Hill, B|D, (ST 81769 69421).

The lettering is somewhat worn but the vertical line between the letters is well defined on the lower part of the stone, which may once have been more deeply buried, and there are traces of a groove on the upper edge.

Right: On the opposite side of the junction to the previous merestone, behind the parish notice board at ST 81768 69431. B|D, deeply inscribed but worn.

(? displaced). Intervisible with middle and right.

Above Middle: Opposite previous merestone, on the east side of the junction of the lane to St Christopher's Church and Road Hill, B|D, (ST 81769 69421).

The lettering is somewhat worn but the vertical line between the letters is well defined on the lower part of the stone, which may once have been more deeply buried, and there are traces of a groove on the upper edge.

Right: On the opposite side of the junction to the previous merestone, behind the parish notice board at ST 81768 69431. B|D, deeply inscribed but worn.

Above Left: East side of Henley Lane, in road verge by the entrance to West Cross at ST82553 67618. Inscribed B D; there is no verical line between the letters but there are traces of the characteristic groove across the upper edge. This stone is the furthest from the present settlement of Ditteridge.

Above Right: North of Alcombe Manor, on verge on west side of lane ST80786975. Inscribed D|B, the letter D is somewhat worn. The stone is broken below the inscription.

Above Right: North of Alcombe Manor, on verge on west side of lane ST80786975. Inscribed D|B, the letter D is somewhat worn. The stone is broken below the inscription.

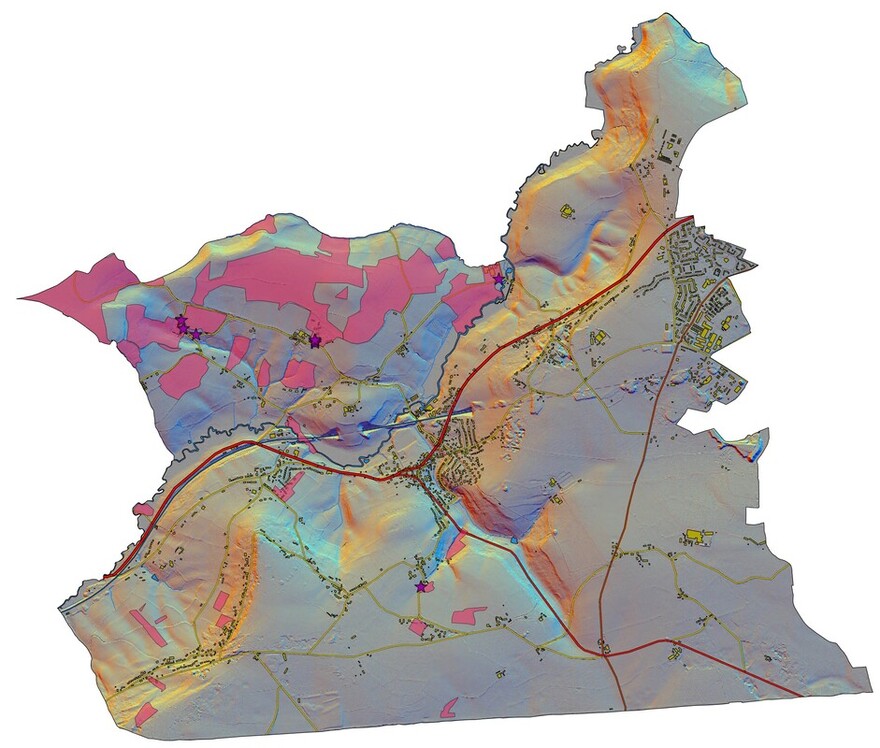

Present extent of Box parish, showing areas belonging to Ditteridge parish in 1838 (pink) and locations of extant merestones (purple stars). Topographic detail: digital terrain model from Lidar data with multiple hill-shading. Contains Environment Agency Information: © Environment Agency and database right 2022

Preserving the evidence

Other merestones may still survive, although there has clearly been considerable attrition. Many of the original stones will have fallen victim to road widening and reconfiguration of property boundaries. None of the stones are protected by formal designation as Listed Buildings. It would be unfortunate were the remaining few stones to be lost or damaged further; the stones are ideal candidates for inclusion on the proposed List of Locally Important Heritage Assets being compiled for the Box Parish Neighbourhood Plan. If any reader knows of other surviving stones, the author would be very pleased to hear from you, so that we may ensure that this particular small piece of our history can be preserved.

Note: the owner of the copyright of the 1626 Allen map shown above could not be traced. We shall be happy to attribute the copyright correctly should the owner contact us.

Other merestones may still survive, although there has clearly been considerable attrition. Many of the original stones will have fallen victim to road widening and reconfiguration of property boundaries. None of the stones are protected by formal designation as Listed Buildings. It would be unfortunate were the remaining few stones to be lost or damaged further; the stones are ideal candidates for inclusion on the proposed List of Locally Important Heritage Assets being compiled for the Box Parish Neighbourhood Plan. If any reader knows of other surviving stones, the author would be very pleased to hear from you, so that we may ensure that this particular small piece of our history can be preserved.

Note: the owner of the copyright of the 1626 Allen map shown above could not be traced. We shall be happy to attribute the copyright correctly should the owner contact us.

References

[1] Sawyer S899: https://esawyer.lib.cam.ac.uk/charter/899.html# . The feature referred to is the Roman road which still forms the southern boundary of Box parish.

[2] National Archives PROB 11/13/474. The bequest to Box consisted of 6s/8d and one of his best cows, which the church wardens were to look after, whilst that to Hazelbury consisted of 3s/4d and a cow, presumably of lesser quality.

[3] The early history of Rudloe, which is not mentioned in Domesday, is poorly documented and it is difficult to determine when it became part of Box parish. Often where parish boundaries form a ‘panhandle’, we may suspect that what was originally a separate estate has become amalgamated with a larger neighbour, as seems to be the case with Rudloe.

[4] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre: 318/3MS; this is a photocopy, made at some point before 1955 and not of the highest quality, of an original in private hands. The location of the original is not known, and some parts of the map are extremely difficult to see..

[5] Apart from several strips of glebe land, the main occupiers were Henry Long and members of the Bollwell family, who were evidently a relatively prosperous family during the seventeenth century

[6] The familiar 22 yard chain of 100 links was developed by Edmund Gunter in 1620, developing the chain described by Aaron Rathborne in 1616. AW Richeson(1966) English Land Measuring to 1800: Instruments and Practices, especially chapter 5

[7] A Winchester (2000) Discovering Parish Boundaries Princes Risborough, Shire, especially pp14-18

[8] This was particularly evident in East Anglia, where examples of two parish churches sharing a single churchyard are common, but such processes may have taken place elsewhere in southern England. P Warner (1986) ‘Shared churchyards, feeemen church builders and the development of parishes in eleventh-century East Anglia’ Landscape History 8, 39-52.

[9] J Ayers (2014) ‘Guide to St Christopher’s Church’ http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/st-christophers.html

[10] The author’s strategy has been to search for the stones at those points where public rights of way intersect with the boundaries of all the separate parts of Ditteridge parish as shown on the 1838 Tithe plans. In a few cases footpaths were so overgrown as to inhibit access, and all those stones listed here are by the sides of roads rather than along footpaths and bridleways.

[1] Sawyer S899: https://esawyer.lib.cam.ac.uk/charter/899.html# . The feature referred to is the Roman road which still forms the southern boundary of Box parish.

[2] National Archives PROB 11/13/474. The bequest to Box consisted of 6s/8d and one of his best cows, which the church wardens were to look after, whilst that to Hazelbury consisted of 3s/4d and a cow, presumably of lesser quality.

[3] The early history of Rudloe, which is not mentioned in Domesday, is poorly documented and it is difficult to determine when it became part of Box parish. Often where parish boundaries form a ‘panhandle’, we may suspect that what was originally a separate estate has become amalgamated with a larger neighbour, as seems to be the case with Rudloe.

[4] Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre: 318/3MS; this is a photocopy, made at some point before 1955 and not of the highest quality, of an original in private hands. The location of the original is not known, and some parts of the map are extremely difficult to see..

[5] Apart from several strips of glebe land, the main occupiers were Henry Long and members of the Bollwell family, who were evidently a relatively prosperous family during the seventeenth century

[6] The familiar 22 yard chain of 100 links was developed by Edmund Gunter in 1620, developing the chain described by Aaron Rathborne in 1616. AW Richeson(1966) English Land Measuring to 1800: Instruments and Practices, especially chapter 5

[7] A Winchester (2000) Discovering Parish Boundaries Princes Risborough, Shire, especially pp14-18

[8] This was particularly evident in East Anglia, where examples of two parish churches sharing a single churchyard are common, but such processes may have taken place elsewhere in southern England. P Warner (1986) ‘Shared churchyards, feeemen church builders and the development of parishes in eleventh-century East Anglia’ Landscape History 8, 39-52.

[9] J Ayers (2014) ‘Guide to St Christopher’s Church’ http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/st-christophers.html

[10] The author’s strategy has been to search for the stones at those points where public rights of way intersect with the boundaries of all the separate parts of Ditteridge parish as shown on the 1838 Tithe plans. In a few cases footpaths were so overgrown as to inhibit access, and all those stones listed here are by the sides of roads rather than along footpaths and bridleways.