Box Disasters and Celebrations Alan Payne September 2022

Many people talk about the spirit of teamwork and clear objectives they experienced in wartime life. This spirit wasn’t engendered solely by the war but was a product of many different social trends such as reverence for king and country and the use of natural disasters to promote national resolve. Both of these techniques were apparent in Box in the late inter-war period.

|

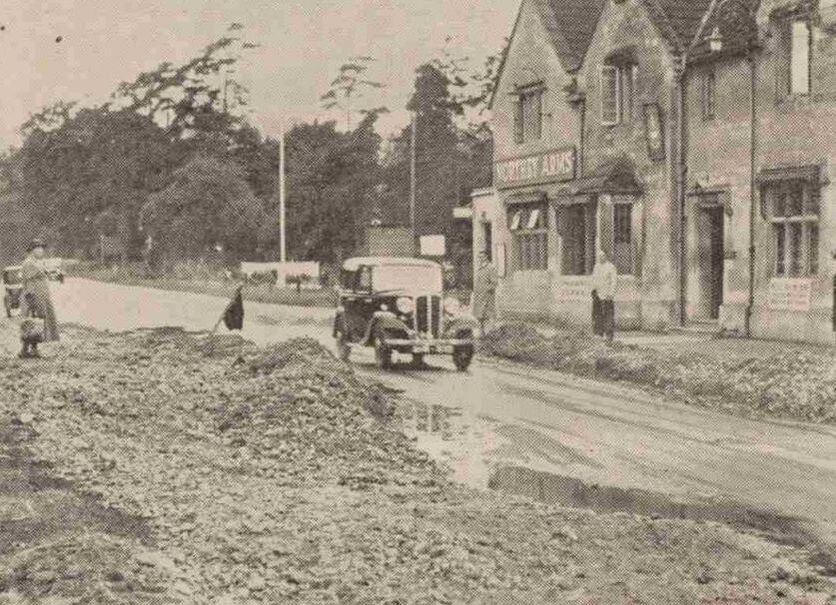

Floods of June 1935 A series of local tragedies started on 26 June 1935 with a flash flood when a freak cloudburst of thunder, lightning and constant rain hit north Wiltshire, turning the Market Place into a swimming pool. At Ditteridge House, Major Cyril Northey observed that 3.6 inches of rain fell between 2pm and 7pm, the most he has ever recorded in a period of over 30 years.[1] Houses were demolished, roads ruined and bridges collapsed. Throughout the Bath and Box areas many people were left stranded at work and children at school. The local newspaper reported the effect in Box village, which had previously enjoyed immunity from heavy thunderstorms for some years.[2] The water came in a torrent down the valley and very soon the houses in the Market Place were flooded. Mr Bence’s shop was flooded (to a depth of three feet). At the top of Mill Lane, the rush of water down Box Hill and Quarry Hill brought down loads of silt and road material and Mr Bray suffered much. At the Northey Arms, the flood water rushed down the hill from Kingsdown and deposited tons of the silt and other material on the main road which was blocked. Traffic on the railway had to stop at about 4am. Box Tunnel was closed from Tuesday afternoon till 11.15 on Wednesday morning. |

John Brooke Flashman Recalled his Family Memories

What happened was that a violent storm broke out one summer's afternoon. The rain was so heavy that the surface water drainage system had no chance whatsoever of coping and a lot of damage was caused to the road surfacing. Number 2 Mead Villas backs on to the recreation field and the whole area was turned into a lake when the downpour continued for three hours. My mother told this story a number of times and it always fascinated me. She always referred to it as a cloudburst.

What happened was that a violent storm broke out one summer's afternoon. The rain was so heavy that the surface water drainage system had no chance whatsoever of coping and a lot of damage was caused to the road surfacing. Number 2 Mead Villas backs on to the recreation field and the whole area was turned into a lake when the downpour continued for three hours. My mother told this story a number of times and it always fascinated me. She always referred to it as a cloudburst.

The scale of the rain exposed how inadequate the infrastructure was in the village and the replacement of many culverts and drains was not accomplished until the 1950s and 1960s.

Aircraft Disappearance, 1936

As the war approached, national events appeared to become even more unsettled. In August 1936 the Imperial Airlines four-engine bi-plane, The Horsa, went missing with its eight passengers and four crew.[3] On the night of 28 and 29 August the plane was trying to land at Bahrain Airport on route to India but the airport was never notified of its arrival and the plane had to attempt a desert landing. No SOS signal or other message was issued on the plane’s communication system after 5.20am local time on 29 August and an RAF Flying Boat was scrambled to look for traces.[4]

As the war approached, national events appeared to become even more unsettled. In August 1936 the Imperial Airlines four-engine bi-plane, The Horsa, went missing with its eight passengers and four crew.[3] On the night of 28 and 29 August the plane was trying to land at Bahrain Airport on route to India but the airport was never notified of its arrival and the plane had to attempt a desert landing. No SOS signal or other message was issued on the plane’s communication system after 5.20am local time on 29 August and an RAF Flying Boat was scrambled to look for traces.[4]

The event had local repercussions as Lieutenant Rupert Crowdy Crowdy (sic) was on board, the only son of Major Albert Edwin Crowdy and his wife Frances Beryl of Downholme, next to Vine Cottage in the centre of Box.[5] Twenty-six-year-old Rupert was returning to his regiment in Bengal after home leave, having being stationed out there for four years.[6] Major Crowdy had a very eventful career, serving with distinction in the Great War and the Indian Army until 1922 and later becoming managing director of a fruit preserving company in Birmingham.[7] The company had gone into liquidation after being subject to a concerted conspiracy by more than 35 men who were charged with fraud.[8]

The RAF had mobilised Flying Boats to investigate and two naval patrol ships joined the search in the Persian Gulf area. National newspapers took up the mystery with reports such as: Where is the Horsa, the giant Imperial Airways liner on the England-Indian service. She must be somewhere.[9] At that time, the desert had no communications and was accessible only on foot or by camel. The Sunday Pictorial carried the report on its front page: No News of British Air Liner with 12 People Aboard.[10] Though they searched unceasingly all day, no sign of the air-liner could be seen.

The airliner was found almost by chance when an RAF search plane from the 84 (Bomber) Squadron was turning back to its base at Shailbah, Iraq. All the passengers were unharmed and the group had to walk two miles across the desert to reach the rescue plane. The good news reached Rupert’s relieved parents at 11 am on 30 August after the travellers had spent a day and most of two nights lost in the desert. Undeterred by the incident, Rupert continued his journey to his regiment and later became engaged to the daughter of a Ceylon tea planter in June 1939.

The RAF had mobilised Flying Boats to investigate and two naval patrol ships joined the search in the Persian Gulf area. National newspapers took up the mystery with reports such as: Where is the Horsa, the giant Imperial Airways liner on the England-Indian service. She must be somewhere.[9] At that time, the desert had no communications and was accessible only on foot or by camel. The Sunday Pictorial carried the report on its front page: No News of British Air Liner with 12 People Aboard.[10] Though they searched unceasingly all day, no sign of the air-liner could be seen.

The airliner was found almost by chance when an RAF search plane from the 84 (Bomber) Squadron was turning back to its base at Shailbah, Iraq. All the passengers were unharmed and the group had to walk two miles across the desert to reach the rescue plane. The good news reached Rupert’s relieved parents at 11 am on 30 August after the travellers had spent a day and most of two nights lost in the desert. Undeterred by the incident, Rupert continued his journey to his regiment and later became engaged to the daughter of a Ceylon tea planter in June 1939.

Village Tragedies in the 1930s

A series of poor health incidents and road accidents seemed to dominate life in the 1930s. The issues touched people’s lives in a dramatic way and almost seemed to anticipate the impending disaster of World War II. The incidents started in 1935 when Louie Chaffey (wife of Arthur Chaffey of Charlotte Cottage, Devizes Road) died aged 70 years. Their 42-year-old daughter Elsie, who had nursed her mother through the illness, passed away in a Bath store whilst buying a mourning outfit for the funeral.

In November 1938 there was a fatal accident when Mrs Louisa Elizabeth Griffin and her daughter Gladys were killed when their car crashed into a stationary lorry outside The Northey Arms on their way to the Bridgwater Carnival. Both women lived at 5 Boxfields and, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see the full tragedy of this unfortunate family. Their older daughter Clara had been killed in 1927 whilst riding pillion on a motor-bicycle and their whole family were involved in the Rising Sun Pub disaster of 1957, in which two of their grandchildren were killed.

A series of poor health incidents and road accidents seemed to dominate life in the 1930s. The issues touched people’s lives in a dramatic way and almost seemed to anticipate the impending disaster of World War II. The incidents started in 1935 when Louie Chaffey (wife of Arthur Chaffey of Charlotte Cottage, Devizes Road) died aged 70 years. Their 42-year-old daughter Elsie, who had nursed her mother through the illness, passed away in a Bath store whilst buying a mourning outfit for the funeral.

In November 1938 there was a fatal accident when Mrs Louisa Elizabeth Griffin and her daughter Gladys were killed when their car crashed into a stationary lorry outside The Northey Arms on their way to the Bridgwater Carnival. Both women lived at 5 Boxfields and, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see the full tragedy of this unfortunate family. Their older daughter Clara had been killed in 1927 whilst riding pillion on a motor-bicycle and their whole family were involved in the Rising Sun Pub disaster of 1957, in which two of their grandchildren were killed.

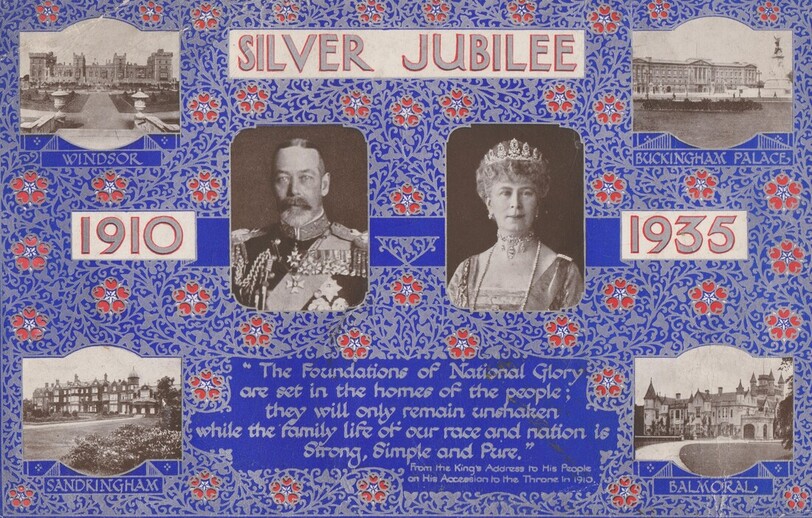

Silver Jubilee of George V

To mitigate the sadness of these events, village residents took part in the happier events celebrated in Box. For his Silver Jubilee, King George V broadcast to the Empire on 6 May 1935, speaking about difficulties to come and remembering those without work. The day started when a crowd of 500 people assembled in the grounds of the Northey Arms for an open-air church service, where the Bishop of Bristol gave an address. Then the crowd processed to The Recreation Ground, one of the first village events held there. Mrs Shaw Mellor led a procession down to a raised throne, accompanied by the Boy Scouts (led by Phil Lambert and Mr Blake) and the Girl Guides (organised by Miss Toy). Here she crowned the Queen of the Revels with dignity befitting the occasion and made speeches of thanks before proceeding to the flagpole to unfurl the Union Jack, which unfortunately did not unfurl according to intentions.[11] There followed folk dancing by schoolchildren, comic football match and stalls offering pillow fights and greasy pole climbing.

Dance music encouraged a few to show their skills and Mr St Clair entertained with conjuring tricks for an hour and a half. Later, the village children sat down to tea and were presented with a jubilee mug and given a present of a day’s holiday the following day from school. This was followed by the broadcast of the Empire’s Greetings, and the King’s speech from 7.40 pm for half an hour, which was listened to by practically everyone in the ground, with silence and interest, which was a mark of the great loyalty between His Majesty and his people. In the evening there was a Chinese lantern procession and fireworks display.[12]

To mitigate the sadness of these events, village residents took part in the happier events celebrated in Box. For his Silver Jubilee, King George V broadcast to the Empire on 6 May 1935, speaking about difficulties to come and remembering those without work. The day started when a crowd of 500 people assembled in the grounds of the Northey Arms for an open-air church service, where the Bishop of Bristol gave an address. Then the crowd processed to The Recreation Ground, one of the first village events held there. Mrs Shaw Mellor led a procession down to a raised throne, accompanied by the Boy Scouts (led by Phil Lambert and Mr Blake) and the Girl Guides (organised by Miss Toy). Here she crowned the Queen of the Revels with dignity befitting the occasion and made speeches of thanks before proceeding to the flagpole to unfurl the Union Jack, which unfortunately did not unfurl according to intentions.[11] There followed folk dancing by schoolchildren, comic football match and stalls offering pillow fights and greasy pole climbing.

Dance music encouraged a few to show their skills and Mr St Clair entertained with conjuring tricks for an hour and a half. Later, the village children sat down to tea and were presented with a jubilee mug and given a present of a day’s holiday the following day from school. This was followed by the broadcast of the Empire’s Greetings, and the King’s speech from 7.40 pm for half an hour, which was listened to by practically everyone in the ground, with silence and interest, which was a mark of the great loyalty between His Majesty and his people. In the evening there was a Chinese lantern procession and fireworks display.[12]

Local Celebrations of Coronation

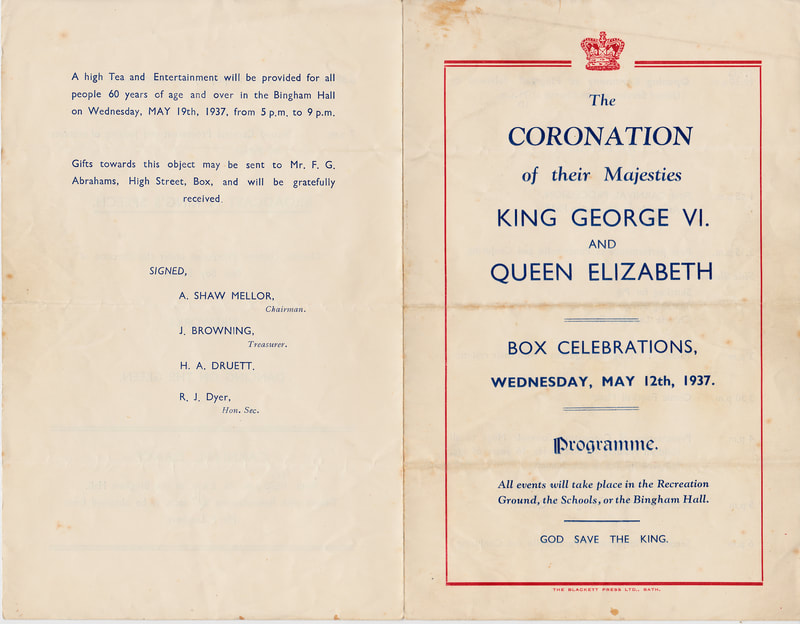

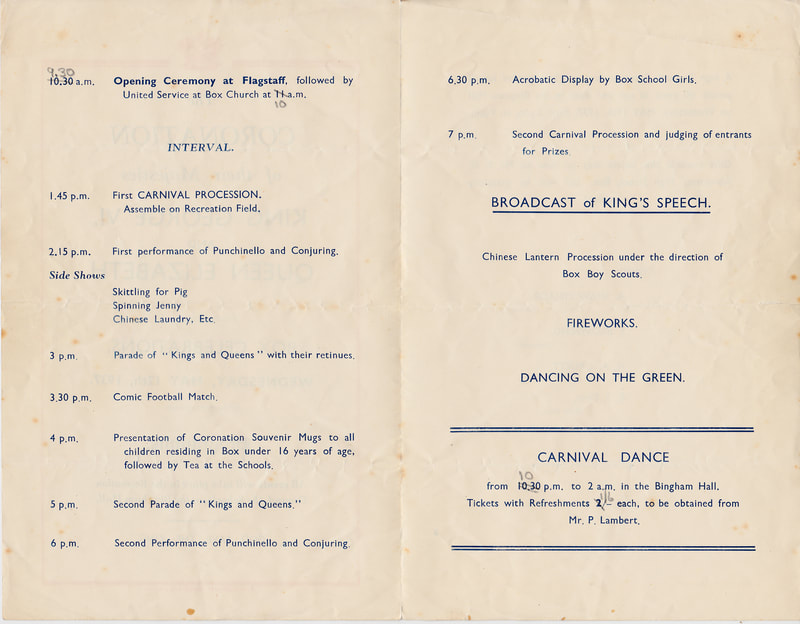

George V died eight months later, followed by the interregnum of Edward VIII until his abdication in December 1936. After so many royal adjustments, the coronation of George VI on 12 May 1937 was a rather improvised event, the date originally planned as Edward’s coronation. It was the first major outdoor event to be filmed for television and the whole event broadcast on the radio. It was also an attempt to show the magnificence of the British Empire and its leaders with the Prime Ministers from each Dominion territory in attendance at the ceremony. The Little Theatre in Bath dedicated whole performances to newsreels of the event and the King’s speech to the nation.[13]

Street parties were an important part of the celebration and Box produced a programme of events, featuring a Parade of Kings and Queens of England put on by the children of Box School organised by the Hon Mrs Dora Shaw Mellor. The Rev Arthur Maltin held services in Box at 8am and 10am. They processed to the Recreation Field accompanied by the Box Girl Guides under Captain G Toy and Lieutenant G Chaffey and the Box Boy Scouts under Scoutmaster Phil Lambert for an opening ceremony at the flagstaff in the Recreation Field. A procession of decorated vehicles followed featuring J and G Browning's Britannia Car and Les Bence's Sports Car and a procession of Kings and Queens with their retinues. In the afternoon there was a radio broadcast of the King's Speech.

George V died eight months later, followed by the interregnum of Edward VIII until his abdication in December 1936. After so many royal adjustments, the coronation of George VI on 12 May 1937 was a rather improvised event, the date originally planned as Edward’s coronation. It was the first major outdoor event to be filmed for television and the whole event broadcast on the radio. It was also an attempt to show the magnificence of the British Empire and its leaders with the Prime Ministers from each Dominion territory in attendance at the ceremony. The Little Theatre in Bath dedicated whole performances to newsreels of the event and the King’s speech to the nation.[13]

Street parties were an important part of the celebration and Box produced a programme of events, featuring a Parade of Kings and Queens of England put on by the children of Box School organised by the Hon Mrs Dora Shaw Mellor. The Rev Arthur Maltin held services in Box at 8am and 10am. They processed to the Recreation Field accompanied by the Box Girl Guides under Captain G Toy and Lieutenant G Chaffey and the Box Boy Scouts under Scoutmaster Phil Lambert for an opening ceremony at the flagstaff in the Recreation Field. A procession of decorated vehicles followed featuring J and G Browning's Britannia Car and Les Bence's Sports Car and a procession of Kings and Queens with their retinues. In the afternoon there was a radio broadcast of the King's Speech.

Box programme of events for coronation of George VI (courtesy Eric Callaway)

All the time that these dramatic events were taking place, the threat of war with Germany was becoming increasingly likely, which overshadowed inter-war issues with disasters of a different magnitude.

References

[1] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 29 June 1935

[2] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 29 June 1935

[3] Ben Lovegrove, 55bomber.wordpress.com., Handley Page HP42 G-AAUC “Horsa” and K Cox Plane Crash 1936 (google.com)

[4] Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 29 August 1936

[5] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 September 1936

[6] North Wilts Herald, 4 September 1936

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 September 1936

[8] Westminster Gazette, 28 January 1925

[9] Portsmouth Evening News, 29 August 1936

[10] Sunday Mirror, 30 August 1936

[11] Parish Magazine, June 1935

[12] Parish Magazine, May 1935

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 22 May 1937

[1] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 29 June 1935

[2] Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 29 June 1935

[3] Ben Lovegrove, 55bomber.wordpress.com., Handley Page HP42 G-AAUC “Horsa” and K Cox Plane Crash 1936 (google.com)

[4] Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 29 August 1936

[5] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 September 1936

[6] North Wilts Herald, 4 September 1936

[7] Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 September 1936

[8] Westminster Gazette, 28 January 1925

[9] Portsmouth Evening News, 29 August 1936

[10] Sunday Mirror, 30 August 1936

[11] Parish Magazine, June 1935

[12] Parish Magazine, May 1935

[13] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 22 May 1937