Continuity and Change Alan Payne March 2022

The inter-war years were some of the most photographed times before mobile phone technology. The reason was lighter, single lens reflex (SLR) technology and cheaper models available for private use, led by manufacturers such as Kodak. As a result, we have many images of Box at that time, showing both how the village was changing and also what remained unaltered.

For many generations, the male members of the Mould family were quarrymen at Box Hill. In 1911 Herbert Mould (1888-) lived with his uncle David Dancey at 5 Tynings Cottages when he was working as a stone sawyer. His parents were George Mould (1824-1900), engine driver for the stone quarries, and Martha Mould (1825-1911). They had rented the same Tynings Cottage premises two decades before in 1891, until other members of the family took over after George’s death in 1900. The Kingsdown family were children of Ben Mould (1858-1926) (himself variously described as farm labourer or general labourer) and Ellen Jane Mould (1846-), who lived on the Lower Kingsdown Road close to Cherry Cottage. Their son also Ben (1883-1970), quarryman, joined the Royal Horse and Field Artillery in 1901 and served throughout the Great War until 1919.

For many generations, the male members of the Mould family were quarrymen at Box Hill. In 1911 Herbert Mould (1888-) lived with his uncle David Dancey at 5 Tynings Cottages when he was working as a stone sawyer. His parents were George Mould (1824-1900), engine driver for the stone quarries, and Martha Mould (1825-1911). They had rented the same Tynings Cottage premises two decades before in 1891, until other members of the family took over after George’s death in 1900. The Kingsdown family were children of Ben Mould (1858-1926) (himself variously described as farm labourer or general labourer) and Ellen Jane Mould (1846-), who lived on the Lower Kingsdown Road close to Cherry Cottage. Their son also Ben (1883-1970), quarryman, joined the Royal Horse and Field Artillery in 1901 and served throughout the Great War until 1919.

However, Box was changing rapidly in the inter-war period with the decline of the local quarry trade in the early 1900s and its failure to revive after the Great War. It wasn’t quarrying but country crafts that Harry Mould from Kingsdown turned to for employment. He was charged with trespassing on Bathford land in search of conies (rabbits) in 1904.[1] In 1916, aged 58, he was described as a thatcher who slipped on a path at Kingsdown (wrongly called Kingswood) and fractured the lower part of his right leg, requiring a trip to the Royal United Hospital in Bath.[2] Many of the rural photos seen in this article strike a chord with us today but were a new feature of the area after the decline of white stone masonry dust and coal smoke from Box Brewery and the Candle Factory.

Changes of Employment on Box Hill

Stone quarrying was a very labour-intensive industry and scores of quarrymen’s houses were built around the excavation sites at Box Hill, Kingsdown and Longsplatt. The decline in the industry meant residents in the hamlets had to seek different occupations.

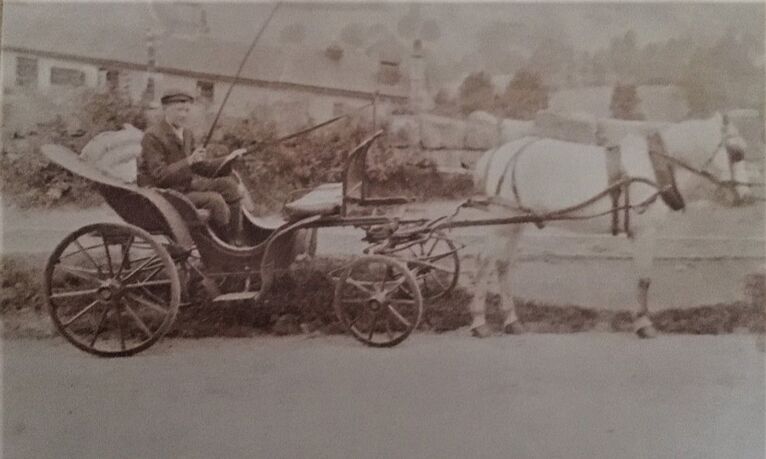

Henry Chandler (1851-7 July 1934) was typical of the people who had to change their employment if they wanted to stay on Box Hill. He started as a mason but after his marriage to Sarah Oatley (1850-11 December 1933) in 1875, he switched trade to run a grocers and bakery business at Box Quarries from about 1881 until 1901. Henry was comfortably off and he appears to have acquired the orchard (now known as The Lycetts) in 1887.[3] It isn’t possible to be certain of the exact house they lived in on the Hill but it appears to be on the A4, up from The Clift. By 1911 Henry had altered his career calling himself Car Proprietor and Grocer. The family later moved closer to the centre of the village to Stanley House and, after that the Great War, he moved again to the Manor House. Here his son Percy ran a business selling petrol, car maintenance and taxi hire on the site of the former wagon and carriage workshop on the forecourt there.

Stone quarrying was a very labour-intensive industry and scores of quarrymen’s houses were built around the excavation sites at Box Hill, Kingsdown and Longsplatt. The decline in the industry meant residents in the hamlets had to seek different occupations.

Henry Chandler (1851-7 July 1934) was typical of the people who had to change their employment if they wanted to stay on Box Hill. He started as a mason but after his marriage to Sarah Oatley (1850-11 December 1933) in 1875, he switched trade to run a grocers and bakery business at Box Quarries from about 1881 until 1901. Henry was comfortably off and he appears to have acquired the orchard (now known as The Lycetts) in 1887.[3] It isn’t possible to be certain of the exact house they lived in on the Hill but it appears to be on the A4, up from The Clift. By 1911 Henry had altered his career calling himself Car Proprietor and Grocer. The family later moved closer to the centre of the village to Stanley House and, after that the Great War, he moved again to the Manor House. Here his son Percy ran a business selling petrol, car maintenance and taxi hire on the site of the former wagon and carriage workshop on the forecourt there.

Sub-Post Offices

The Post Office on Box Hill was a similar story to the Chandlers. The building on the A4 (sometimes called Southview, now known as Highway) opened as a sub-post office in 1925 and operated until just after the Second World War. It was run by the Sheppard family: first, Walter T Sheppard and his wife Sarah Jane for 15 years, then by their son Thomas, and lastly by the granddaughter, Joan Sheppard.[4] Walter described himself as quarryman labourer in 1901 and 1911 but converted to running the shop after the Great War. At times, it would have been hard for Thomas to run the business as his lost his wife Phyllis when she was only 29, leaving him and his mother to manage five infant children and the business.[5] The telephone box which previously stood next to the shop was erected in 1938.[6]

Much the same happened in other hamlets. At Kingsdown the post office, general store and bakery business, operated by John Brooke from 1899 to 1926, limped on but in reduced circumstances. John Allan Pratt and his wife Lisa took over the business but the general store was untenable by 1939. Ironically, John Pratt was himself charged with speeding in his car in Bristol in 1938 shortly before becoming a special constable in the Second World War.[7] At Jessamine Cottage, next door, Ernest Wilkins assisted with the baking and sold bread directly from his house which was called Jessamine Bakery in 1939 and his son, William J Wilkins called himself Van man grocery trade, taking goods around the hamlet.

The Post Office on Box Hill was a similar story to the Chandlers. The building on the A4 (sometimes called Southview, now known as Highway) opened as a sub-post office in 1925 and operated until just after the Second World War. It was run by the Sheppard family: first, Walter T Sheppard and his wife Sarah Jane for 15 years, then by their son Thomas, and lastly by the granddaughter, Joan Sheppard.[4] Walter described himself as quarryman labourer in 1901 and 1911 but converted to running the shop after the Great War. At times, it would have been hard for Thomas to run the business as his lost his wife Phyllis when she was only 29, leaving him and his mother to manage five infant children and the business.[5] The telephone box which previously stood next to the shop was erected in 1938.[6]

Much the same happened in other hamlets. At Kingsdown the post office, general store and bakery business, operated by John Brooke from 1899 to 1926, limped on but in reduced circumstances. John Allan Pratt and his wife Lisa took over the business but the general store was untenable by 1939. Ironically, John Pratt was himself charged with speeding in his car in Bristol in 1938 shortly before becoming a special constable in the Second World War.[7] At Jessamine Cottage, next door, Ernest Wilkins assisted with the baking and sold bread directly from his house which was called Jessamine Bakery in 1939 and his son, William J Wilkins called himself Van man grocery trade, taking goods around the hamlet.

Road Changes in Box

Similar changes were occurring in the centre of Box where the old industries of brewing and candle-making were in deep decline. Widespread areas of land had previously been needed for stone transportation, steam engine movement and extensive milling at Box Mill. Instead, by the inter-war years, motor traffic kept to the designated road system which were obliged to undergo substantial improvement.

The use of tarmac (melted tar) to replace crushed stone as the road surface became more common as motor vehicles replaced horse-drawn carriages. The method was devised just before the First World War and the boom years for its use were in the mid-1930s. The arterial roads were the first to be improved and there were plans to tarmac the road from Bath to Shockerwick in 1919.[8] It was very expensive and by 1926 it is estimated that there were still only 190 miles of such roads in England.[9]

Most in Box tracks remained dirt and gravel which threw up quantities of dust until after the Second World War but the verges were clear of plastic, carboard boxes and the litter we experience today.

Similar changes were occurring in the centre of Box where the old industries of brewing and candle-making were in deep decline. Widespread areas of land had previously been needed for stone transportation, steam engine movement and extensive milling at Box Mill. Instead, by the inter-war years, motor traffic kept to the designated road system which were obliged to undergo substantial improvement.

The use of tarmac (melted tar) to replace crushed stone as the road surface became more common as motor vehicles replaced horse-drawn carriages. The method was devised just before the First World War and the boom years for its use were in the mid-1930s. The arterial roads were the first to be improved and there were plans to tarmac the road from Bath to Shockerwick in 1919.[8] It was very expensive and by 1926 it is estimated that there were still only 190 miles of such roads in England.[9]

Most in Box tracks remained dirt and gravel which threw up quantities of dust until after the Second World War but the verges were clear of plastic, carboard boxes and the litter we experience today.

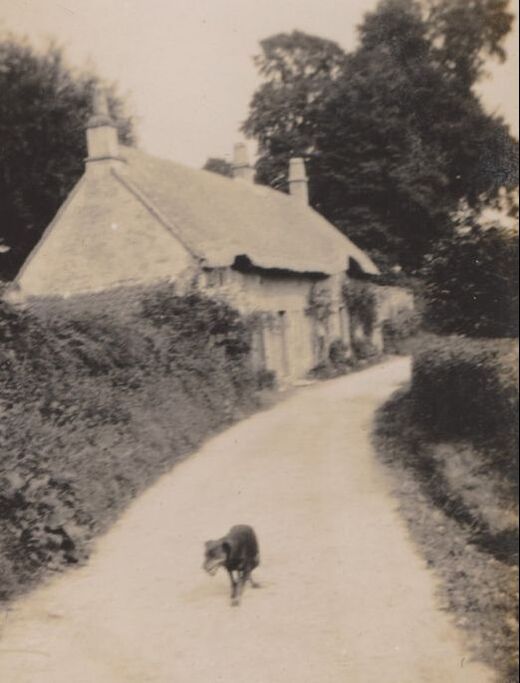

Many of the roads in Box were more like our concept of tracks: without pavements, line markings, cats-eyes or passing places. Above Left: The road at Middlehill and Right: Unknown location in Box, possibly Ditteridge (both photos courtesy Hugh Sawyer).

Enhancing Box’s Woodland

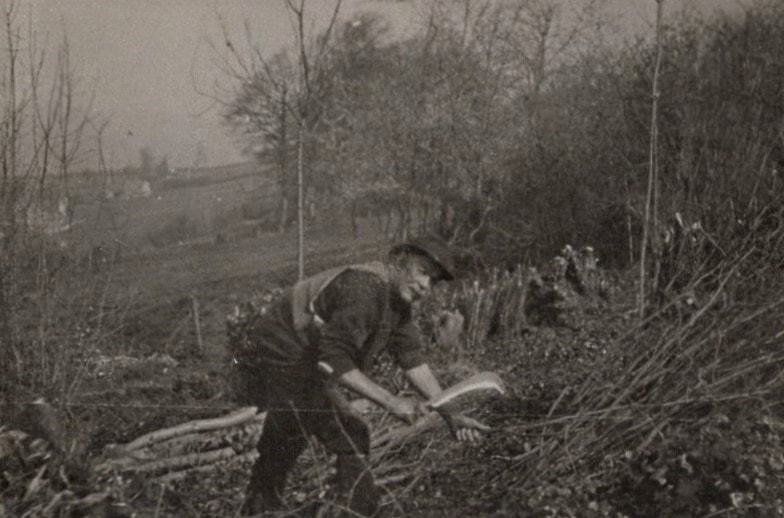

Britain had ceased to harvest wood systematically in the Victorian period, relying instead on imported timber. During World War I imports were greatly restricted and government measures were taken to reverse these trends starting with the Forestry Commission founded in 1919. We see these trends in village photos during the inter-war years. In some areas the woodland which existed was overgrown and uncultivated or sparse and straggly (seen below left beside the By Brook). In other locations there was work involved in pollarding the trees (seen below right at Kingsdown). Both pictures are courtesy John Brooke Flashman.

Britain had ceased to harvest wood systematically in the Victorian period, relying instead on imported timber. During World War I imports were greatly restricted and government measures were taken to reverse these trends starting with the Forestry Commission founded in 1919. We see these trends in village photos during the inter-war years. In some areas the woodland which existed was overgrown and uncultivated or sparse and straggly (seen below left beside the By Brook). In other locations there was work involved in pollarding the trees (seen below right at Kingsdown). Both pictures are courtesy John Brooke Flashman.

Conclusion

Many years later, a poignant (but perhaps overly-nostalgic) piece was written for the Parish Magazine, which encapsulated living in a peaceful, rural community between the Wars: I have often been asked what Ashley was like in the old days and the memories come flooding back. Such a pretty little hamlet, dear little cottages in the corner where the modern houses now stand (uncertain if the author means Littlemead or Ashley Lane). Lamp lighting but no streetlights – later gas lighting and no telephone box. The common and the trees and on to Totney staircase – the large chestnut tree with a swing where children spent many happy hours – and never getting wet because of its size. Three elderly ladies (sisters) kept the laundry on the common where the ‘gentry’ sent baskets of laundry each week – all done by hand – and lily white. The farm was kept by a bad-tempered farmer who scared young children to death chasing them from his fields, but a little apple stealing succeeded. Horse drawn hay carts provided much fun, everyone helping to get the hay in.

Water was drawn from wells, which made washing days very tiring. Gardens and allotments attended to with pride – fresh vegetables free from pesticides. Acorns gathered for pig food – hips for syrup and eggs collected for the troops, quinces for food in World War I, also a serious flu epidemic. The firing range where troops came for training and the RAF camp along Ashley Road where many huts now stand.

The tiny post office where sweets and postal goods were sold was in a cottage in the Barton. Anyone for a piece of liquorice – one halfpenny? Milk was fetched from the farm each day either in a can or a jug. Hot bread was delivered every day by the local baker by a horse-drawn van. Long walks to school either by road or field and home to lunch each day – no school milk or meals. A great favourite was the Ashley blacksmith, his roaring fire was always welcome. A very well-loved doctor who came visiting houses on horseback day or night and in his spare time he taught the local children to swim in the brook near the mill.

Kingsdown sheep fair every September 15th was always enjoyed, watching the sheep being driven there from Colerne and surrounding districts, this was always well attended. A yearly trip to Weston-super-Mare for the children by steam train was another treat – for many this was a holiday as wages were low and no holiday pay. Often the porters would ask the driver of the train ‘Hang on a minute mate, someone coming down the hill’ and they cheerfully did. No buses but open top trams from Bathford to Bath – not such fun on a wet day. Life then in a little hamlet was very happy and peaceful, a community who shared each other’s joys and sorrows.[10]

Many years later, a poignant (but perhaps overly-nostalgic) piece was written for the Parish Magazine, which encapsulated living in a peaceful, rural community between the Wars: I have often been asked what Ashley was like in the old days and the memories come flooding back. Such a pretty little hamlet, dear little cottages in the corner where the modern houses now stand (uncertain if the author means Littlemead or Ashley Lane). Lamp lighting but no streetlights – later gas lighting and no telephone box. The common and the trees and on to Totney staircase – the large chestnut tree with a swing where children spent many happy hours – and never getting wet because of its size. Three elderly ladies (sisters) kept the laundry on the common where the ‘gentry’ sent baskets of laundry each week – all done by hand – and lily white. The farm was kept by a bad-tempered farmer who scared young children to death chasing them from his fields, but a little apple stealing succeeded. Horse drawn hay carts provided much fun, everyone helping to get the hay in.

Water was drawn from wells, which made washing days very tiring. Gardens and allotments attended to with pride – fresh vegetables free from pesticides. Acorns gathered for pig food – hips for syrup and eggs collected for the troops, quinces for food in World War I, also a serious flu epidemic. The firing range where troops came for training and the RAF camp along Ashley Road where many huts now stand.

The tiny post office where sweets and postal goods were sold was in a cottage in the Barton. Anyone for a piece of liquorice – one halfpenny? Milk was fetched from the farm each day either in a can or a jug. Hot bread was delivered every day by the local baker by a horse-drawn van. Long walks to school either by road or field and home to lunch each day – no school milk or meals. A great favourite was the Ashley blacksmith, his roaring fire was always welcome. A very well-loved doctor who came visiting houses on horseback day or night and in his spare time he taught the local children to swim in the brook near the mill.

Kingsdown sheep fair every September 15th was always enjoyed, watching the sheep being driven there from Colerne and surrounding districts, this was always well attended. A yearly trip to Weston-super-Mare for the children by steam train was another treat – for many this was a holiday as wages were low and no holiday pay. Often the porters would ask the driver of the train ‘Hang on a minute mate, someone coming down the hill’ and they cheerfully did. No buses but open top trams from Bathford to Bath – not such fun on a wet day. Life then in a little hamlet was very happy and peaceful, a community who shared each other’s joys and sorrows.[10]

References

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 8 October 1904

[2] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 8 July 1916

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 11 August 1887

[4] Courtesy Elaine Woodgate who lived opposite

[5] The Wiltshire Times, 19 February 1927 and Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 March 1938

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 2 April 1938

[7] Western Daily Press, 3 June 1938

[8] Bah Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 17 May 1919

[9] http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/Museum/Tarmac/Group.htm

[10] Parish Magazine, June 1980

[1] The Wiltshire Times, 8 October 1904

[2] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 8 July 1916

[3] The Bath Chronicle, 11 August 1887

[4] Courtesy Elaine Woodgate who lived opposite

[5] The Wiltshire Times, 19 February 1927 and Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 5 March 1938

[6] The Wiltshire Times, 2 April 1938

[7] Western Daily Press, 3 June 1938

[8] Bah Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 17 May 1919

[9] http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/Museum/Tarmac/Group.htm

[10] Parish Magazine, June 1980